Refusal as Repair Reflections on Disorganising

Introduction

A myriad of crises define our current moment: ecological, economic, and migratory; the crisis of freedom; the crisis of funding; the care crisis; and the human rights crisis. The accumulation of these overlapping crises constitutes what I refer to as the “crisis context.” When ruminating on these moments of crisis within the context of art institutions in 2021, critic and writer Maddee Clark posed the question “is the artworld in a perpetual state of crisis?”1 Responding to the “theatrical and doom-laden” language that characterises contemporary art writing, Clark argued that “for as long as I’ve been involved in the white art world, it’s been in varying forms of crisis.”2 In this article I take up Clark’s polemical line of questioning and examine the relationship between art and crisis through a case study of the curatorial-cum-institutional project Disorganising. The project comprised of an open and expanding conversation that interrogated working practices, and was held across three independent institutions based in Naarm (Melbourne, Australia): Bus Projects, Liquid Architecture (LA), and West Space.3 I first began writing this article as Disorganising was coming to an end in late 2021. This aligned with Melbourne’s sixth and final COVID-19 lockdown being lifted.4 Across four distinct sections, I give my personal account of Disorganising: “Living from Work,” which explores how Disorganising functioned during the pandemic; “Repair,” which situates Disorganising within a climate tasking artists with aiding economic recovery; “Refuse,” which looks at examples to counter these expectations of recovery; and finally, “Return,” which speculates on what might happen next. By way of conclusion, this article considers “How to End Disorganising?” and asks how one might evaluate projects of this nature.

Disorganising began as an ongoing conversation between the four Directors of West Space, LA, and Bus Projects. These conversations came about in response to shared challenges: the suspension of programs due to the global pandemic in March 2020 and each organisation losing significant ongoing federal multi-year funding, a development announced in April 2020. These conversations grew to include other staff working at each organisation and in July 2020, through successful state “reinvigorate” funding streams, Disorganising expanded from an internal conversation to a public project. In November 2020, West Space, LA, and Bus Projects simultaneously released joint statements via their mailing lists which announced the recruitment of two new part-time positions to aid with Disorganising. In 2021, Associate Producer Lana Nguyen and Associate Editor Xen Nhà joined the cohort. Across the following months, numerous artistic collaborators were welcomed into the fold at the invitation of Nguyen and Nhà.5 Nguyen and Nhà worked between the three organisations interpreting, responding to, and challenging institutional habits and biases, guiding the development of the project with care and critique. On their first day, working with former West Space Curator Tamsen Hopkinson, Nguyen and Nhà devised a set of guiding protocols for the project. Over the coming months Nguyen and Nhà commissioned artists and writers to respond to these shared working conditions and to experiment with alternate modes of organising to varying levels of publicness. Nguyen and Nhà liaised between the artists and the institutions, guided by a central question: “when we disorganise, are we also asking what needs to be organised and reorganised individually and collectively in our systems and institutions?” Disorganising operated on two interwoven planes: the “internal” work between the institutions, including meetings and critical reflection writing practices, and the “external” work with artists and the public.6 This “external” work included dinners, workshops, co-authored newsletters, audio archives, and roundtables. These internal and external divides—as was the nature of the project—bled into each other. Disorganising collaborator and LA’s former director, Joel Stern defined the gambit of the project ambitiously, writing that “Disorganising begins with the attempt to recognise, name and diagnose common challenges and complexes—and then proceeds through a process of collaboration and expansion with artists—and then continues through being alive and alert to the generative possibilities of the works.”7

In the summer 2021 and 2022, the Australian government abandoned its policies and strategies for “Covid-Zero” and instead proposed we learn to live with the virus, prioritising individual responsibilities over collective care. Case numbers across the Eastern states of Australia skyrocketed, childcare once again became a risk and my family members contracted the coronavirus, subsequently needing to isolate. Disorganising was a product of these pandemic conditions: their frustrations, distances, proximities, and reflections.

Living from Work: the context of disorganising8

Stocking supermarket shelves, food preparation and delivery, dispensing COVID-19 tests, caring for mental and physical health, providing financial and emotional support for those who lost income, caring and educating children: this is the reproductive labour that maintained society under the conditions of the pandemic. This “maintenance” has led to a reconsideration of “essential” work: healthcare, education, hospitality, food production and transport workers have been retitled as “frontline” workers. Frontline workers were exposed to COVID-19 to maintain day-to-day operations under “the new normal.”9 “Compassion fatigue” (the inability to feel compassion as a result of overexposure to trauma, suffering, or stress) was and is a very real consequence for the aforementioned essential workers, care providers, and parents, who have been stretched to a breaking point over the course of the pandemic.

Prior to the onset of the global pandemic in 2020 and subsequent lockdowns beginning in March, the year began with significant changes for each of the three participating institutions. West Space, LA, and Bus Projects all relocated from their previous venues across Melbourne to occupy separate tenancies at Collingwood Yards, a multi-arts precinct in Melbourne’s inner-north, Yálla-bir-rang on unceded Wurundjeri lands. The relocation was key for the strategic planning of each organisation, building upon their long histories of artist-led and experimental programming across Melbourne. The move also situated each organisation within a professionalised community of creative peers. In late March of that year, before West Space opened its inaugural exhibition, each organisation’s artistic program was indefinitely suspended due to the pandemic. Several weeks into the state of Victoria’s stay at-home-orders, each organisation received notification that their applications for ongoing multi-year or four-year funding from the Australia Council for the Arts was unsuccessful. West Space had received multi-year funding from Australia Council since 2012. This funding offered the organisation a new level of professionalisation. For the first time in the organisation’s history, West Space was able to pay artist fees to exhibiting artists and provide relative job security for employees.10 Similarly, LA had historically received multi-year federal funding. Bus Projects, the more emergent of the three organisations, was following in the footsteps of West Space and LA, hoping to secure a comparable level of ongoing financial support. Multi-year funding is a lifeline for many organisations, funding staff salaries, artist fees, and rent—areas not often covered by project grants or private trusts and foundations. The payment of these essential maintenance costs enables the long-term programming that benefits both artists, publics, and the institutions themselves.

“Why,” asked writer and unionist Ben Eltham, “would the Australia Council slash arts funding during the worst crisis in Australian culture in a century?”11 The answer to his question arguably lies in the way that conditions of the art world have shifted since the late twentieth-century, especially since the 2008 financial crisis. The pervasive expansion of neoliberalism in the arts has resulted in the increased privatisation of the sector. Organisations are placed in direct competition for dwindling public and private funds and there is a consistent pressure for growth and expansion to justify and maintain support from government at the local, state, and federal level. At the same time, the Australian Federal Government arts budget has shrunk by twenty percent since 2013, when Tony Abbott and the Liberal Party assumed leadership.12 With larger organisations occupying the majority of the funding base through streams such as the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts’ RISE Fund, there is little room to fund small-to-medium sized organisations.13 Without the promise of ongoing multi-year federal funding, West Space, LA, and Bus Projects and other organisations of their scale are forced to reapply each year for alternate funds to deliver the forthcoming year’s program, pay wages and cover other essential operating costs. The result of the withdrawal of this funding is that staff face employment insecurity, projects have short lead times, and institutions are forced to operate under a state of precarity. This unstable climate is what lay the foundations for Disorganising.

Despite the shuttered venues and suspended programs resulting from COVID-19, arts organisations continued to operate and maintain business (busyness) as usual. However, “with little art to see,” writer and critic Dan Fox observed, “attention turned to structural issues.”14 For many institutions, the pause of live events and exhibitions was an opportunity for introspection. This led to the development of digital programs that questioned the role of institutions. The ability of art institutions to foster and support social change was already a burgeoning conversation, one that had been building since 2016 in response to Donald Trump’s presidential campaign in the United States and across Europe, the United Kingdom and Australia in response to the rise of populism.15 Zoom and other digital platforms facilitated international institutional collaboration and enabled arts organisations to reach new global audiences. Organisations were given space to examine their position within the broader, planetary arts ecology, addressing dimensions of their history as products of colonial and capitalist forces or their future contributions to a post-pandemic life.16 An Australian example includes the Melbourne-based Australian Centre for Contemporary Art’s series of talks, Defining Moments: Australian Exhibition Histories 1968–1999 (2020).17 Moreover, in 2021, West Space, Para-Site (Hong Kong), Western Front (Vancouver, Canada), and Enjoy Contemporary Art Space (Te Whanganui-a-Tara/Wellington, Aotearoa/New Zealand) came together for the symposium The Region: dialogues on the power and precarity of artist self-organisation in the Asia-Pacific. In 2022, The Institute of Modern Art in Brisbane ran a series of talks titled Net Positive: What does a better art institution look like?18 These conversations were not confined to Australia—they reverberated around the globe. In the United States, SculptureCentre (New York) and The Artist’s Institute (New York) collaborated on the conversation series Artist, or Institution and in Europe, State of Concept (Athens, Greece) launched the Bureau of Care.19

Paused programming in 2020 and 2021 offered a unique opportunity for internal introspection and assessment. Yet institutions continued their public programming, motivated by maintaining opportunities for artists and the need to satisfy outcomes from funding bodies. Australia’s federal government implemented the JobKeeper Payment, a twelve-month (March 2020 to March 2021) long government subsidy that paid eligible businesses to retain staff. Even by name, the JobKeeper Payment suggests work is valuable and needs preserving over and above the livelihood of citizens and their quality of life. The regular payment of A$1,500 resembled a universal basic income, providing some artists and artworkers with more stability than they had enjoyed pre-pandemic.20

Disorganising was not immune to the ongoing creation and continuation of work. Paradoxically, while attempting to “disorganise,” each of the three organisations maintained their own program of exhibitions, performances, and talks. One of the central contradictions of the project was how much work it generated. As a curator and the Director of West Space, it was expected that my work continue from home.21

Repair

Queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s pioneering essay “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, Or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Essay is About You” argues for “reparative critical practices” that facilitate “changing and heterogeneous relational stances,” rather than rigid theoretical ideologies.22 In the same vein, I position Disorganising as a reparative curatorial strategy or practice that “surrenders the knowing.”23 As a project that encompassed three organisations, their staff, their boards, their stakeholders, as well as a changing cohort of artists, documentarians and writers, it was an expansive, generative, contradictory, and changeable project. In her book On Freedom: Four Songs of Care and Constraint (2021), writer Maggie Nelson extends Sedgwick’s concept of reparative critical practices to what she terms as “the reparative turn in contemporary art.” For Nelson, the reparative turn “presumes the audience to be damaged, in need of healing, aid, protection.”24 In the case of a reparative curatorial strategy, we assume that the institution, and the systems of funding that it is bound to, is damaged and in need of repair.

“The arts bloodbath has outrun the arts’ output—the crisis is the story,” quipped critic and curator Lauren Carroll Harris in response to the mainstream media’s reporting on the arts.25 Carroll Harris observed how this mode of reporting favoured stories of crisis, scarcity, and overcoming adversity as opposed to reviews, criticism, or other meaningful engagement with artwork. Over the course of 2020, 2021, and into 2022, mainstream media and arts publications alike have played an equal role in this equation. Countless articles have urged for government support for the arts sector after it was left “decimated” by COVID-19. Yet at the core of this (perhaps) dramatic discourse, the crisis felt by artists and arts workers was and is very real. At the height of the pandemic, it was particularly exacerbated by the high proportion of casual workers and freelancers within the sector. These precarious working conditions meant that arts workers were excluded from government subsidies.26

Counterbalancing crisis rhetoric is the media cycle that promotes stories of artists’ resilience.27 The economic and creative contributions of the creative industries are heralded as key to a post-COVID economic recovery. Recommendations were made to the Australian government that requested investment in creative workers to boost the economy and aid in the post-pandemic recovery.28 However, these responses to crisis remain “an endorsement of the sector as it stands” and the value of cultural work is tied to a worker’s capacity to produce economic value—namely in the form of gross domestic product.29 In addition to economic recovery, artists, as the peak of the “creative industries,” are also being called upon to offer creative solutions to isolation, overwork, boredom, and uncertainty. Ben Eltham and Benjamin Law have argued that Australians turned to culture during lockdowns to sustain connection and to provide entertainment during isolation.30 New expectations of creative adaptability added new pressures for artist productivity.31 This desire for productivity has been further incentivised during the pandemic by artist grants, digital commissions, stay-at-home residencies, and what funding bodies called “reimagined funding.” Each of these opportunities testifies to artists’ and art workers’ perceived ability to continue working in the face of adversity. In framing the artist as a figure possessing creative solutions for recovery, contemporary crisis discourse proposes and maintains the principles of scarcity.

Nika Dubrovsky and David Graeber’s two-part essay “Another Art World” claims that “any market of course must necessarily operate on a principle of scarcity … for profits to be made, scarcity has to be produced.”32 The longstanding romanticised concept of the artist as an individual genius preserves the scarcity principle. This ideal is continually produced and maintained by the critics, curators, funders and investors or what Dubrovsky and Graeber refer to as the “critical apparatuses” of the artworld—or by another name, gatekeepers. The reoccurrence of crisis rhetoric in mainstream discussions of contemporary art further reproduces scarcity. Firstly, this rhetoric reinforces the very real challenges faced by artists, including precarity of income, workplace casualisation, and proliferation of debt. Secondly, it further reproduces this scarcity by singling out the figure of the artist as an agent of recovery who is tasked with kickstarting said recovery.

Disorganising was underwritten by a strategic investment from Creative Victoria, the state of Victoria’s funding body, with the specific intention of reinvigorating the economy during the pandemic. The project was awarded A$180 thousand out of a total of A$7.9 million. This pool of funds was available to ninety-nine eligible organisations, with priority given to applicants that demonstrated the following qualities: “stabilisation,” “adaptation,” “connectedness,” “resilience,” and “agility.” Whereas other recipients future-proofed their organisations by building new digital infrastructure, undertaking business development, or creating outdoor exhibition venues, Disorganising took a more unconventional route. The program utilised the strategic funding to underwrite an experiment in quasi-collective institutionalism born out of a refusal for peer organisations to remain in competition with each other for dwindling resources. In our public statement, published in November 2020, Disorganising asked: “What would it mean, at a moment of precarity, to become institutionally inseparable?”33 Informing this line of questioning were international precedents such as Arts Collaboratory, a group of twenty-five organisations, mainly outside of the global north, aided by the siphoning of Dutch capital from the Mondrian fund.

This proposition was not a “pathway to a merger” or a business plan. As directors, we did speculate on the possibility of said action but we were aware of the neoliberal impulse that would encourage the streamlining of an institution through a merger—funding one organisation instead of three, for example. Instead, Disorganising was an exercise in finding new ways of working and collaborating, informed by place and site, on stolen Aboriginal land. It was an opportunity to bind our (institutional) selves together, emphasising of our indivisibility as organisations rather than enact the scarcity principle that forces “gladiator-style” competition between organisations. Disorganising met all the aforementioned criteria stipulated by Creative Victoria. It also “responded to the new environment” of the pandemic by questioning the present and the future conditions of creative work.

In response to the task of economic recovery, Disorganising asked, “what is worth recovering?” Or as Disorganising collaborator and Associate Editor Xen Nhà put it, “what parts of the institution need to die for something else to grow?” One of the most significant challenges of Disorganising was the funding timeline. Although the project would not have been possible without Creative Victoria funding, compromises were made that were antithetical to the nature of the project.34 The project ultimately conformed to external timelines dictated by the funding body, despite intensions of slowing down. The pressure to work within the funding timeline was a major compromise to the project and curtailed its potential radicality. Would a future program be able to undo or subvert the logic of the funding timeline?

Refusal

Quite apart from the organisation as a concept, refusal is also a key strategy when organising labour. Bargaining strategies such as withdrawing, striking, or boycotting have won improvements in workers’ rights and contributed to better working conditions throughout the world. More recently, scholars have turned their attention to the refusal of work point blank. David Frayne in The Refusal of Work: The Theory and Practice of Resistance to Work (2015) explores the moral obligation of work, and those who refuse it. Arguing for refusal as a radical departure from the norm “in the context of a society where work is the most accepted way to gain status and a sense of identity.”35 Strategies of refusal have brought about fundamental changes to the structures of boards and institutions. This tactic is perhaps best exemplified by a recent Australian example: when a group of artists withdrew their participation in the 19th Biennale of Sydney in 2014 due to the Biennale’s funding ties to Transfield Holdings. The company’s subsidiary Broadspectrum, formally Transfield Services, operated the Australian government’s immigration detention facilities on Nauru and Manus islands between 2012 and 2015.

We frequently spoke of refusal in our internal Disorganising conversations. In the public statement announcing Disorganising, the directors of each institution posed the question “How, as independent organisations, might we refuse to compete with each other for resources, and the attention of audiences, artists, stakeholders?”36 Later, Nhà quoted geographer and sound artist AM Kanngieser in a Disorganising newsletter:

Refusal is also what AM Kanngieser describes as “return.” The etymology of refusal means to give back, to restore, to return, derived from re-, “back,” and fundere-, “to pour.” Liquid thinking. One understanding of refusal as return: “a (re)turning to an (un)known because nothing ever returned to its self-same or absolute—unsettles narratives of resistance that are framed only in opposition.”37

For Disorganising, there was neither a refusal to work nor was there a boycott or strike. The refusal was angled towards productivity and competition: a refusal to “recover.”

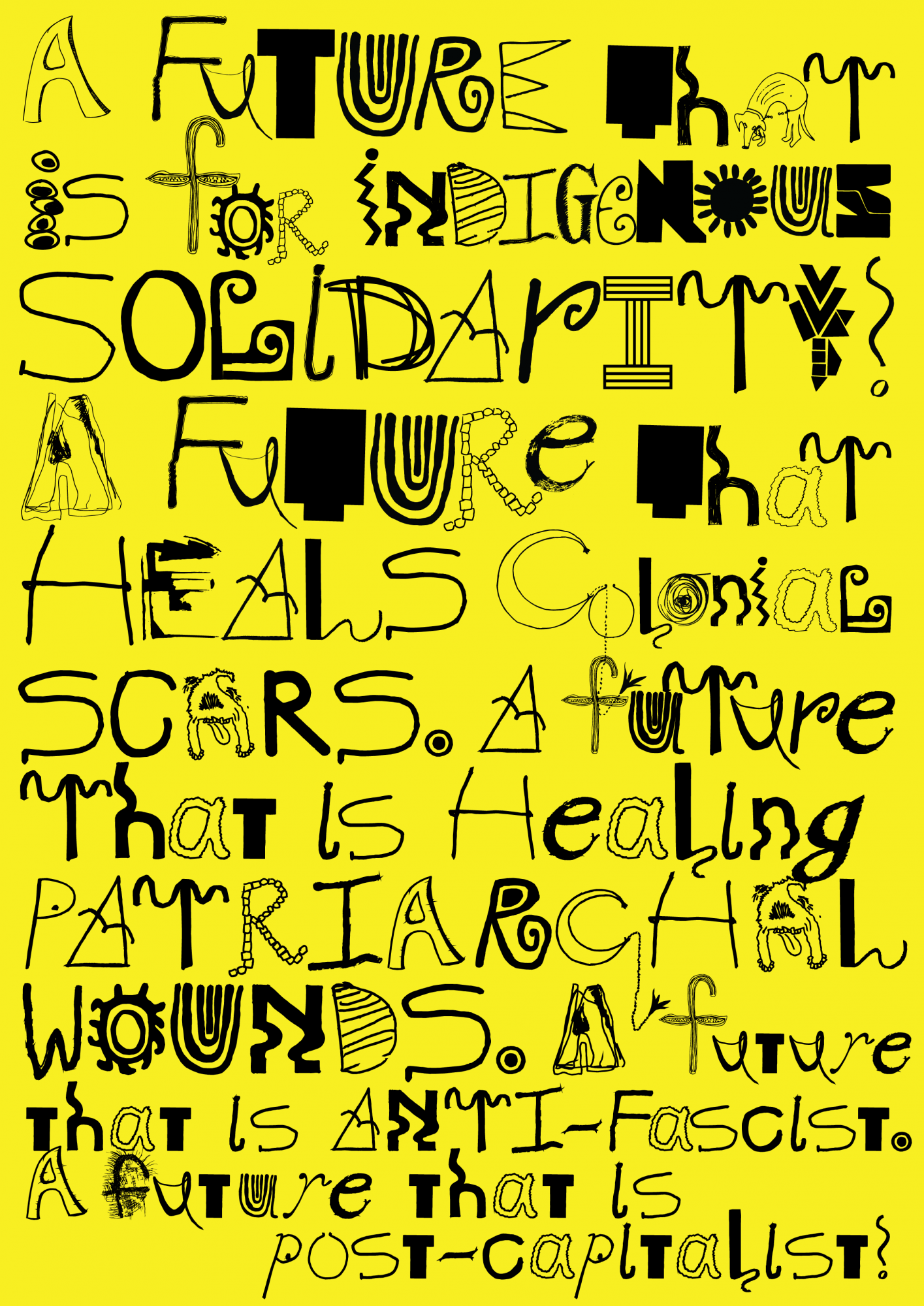

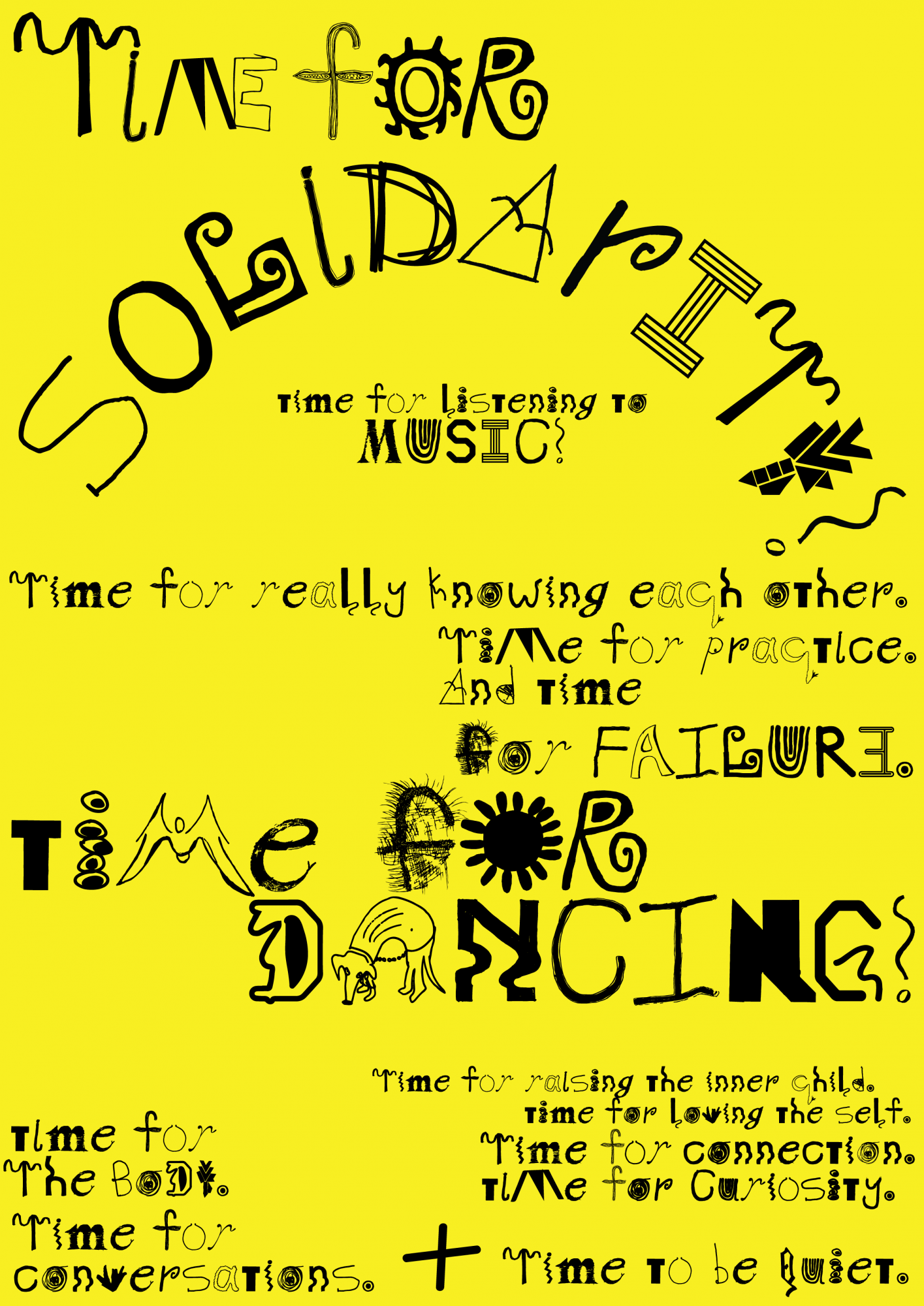

Disorganising had a complex relationship to work. Although there was a significant number of artworks and texts commissioned and produced through the expertise of Nhà and Nguyen, I found that a collaboration between the three organisations was rarely “productive” in the neoliberal sense of the word. As Nguyen pointed out, perhaps our programmatic impulse reduced the capacities for internal work between the three organisations. This was and remains the central contradiction of the project; in exploring new ways to work, more work was generated. My own input and relationship to the project was equally contradictory. I struggled to find the time to commit to deep practices of critical reflection, and it was a constant challenge to prioritise Disorganising over other aspects of my work. At the same time, I wanted to refuse the rhetoric of recovery that demanded the continuation of work but for the aforementioned reasons felt I couldn’t. As Melbourne moved through six lockdowns in twenty months, I felt my time contract and expand with changing responsibilities and work environments, particularly as my child was repeatedly pulled out of childcare or school with little notice. Because of this shift in care relations, Disorganising was one of the few professional experiences that synthesised my paid work as a Director with my unpaid work as a mother. Childcare was provided at the few in-person events we had and when events moved to Zoom, my child participated alongside me. One of the projects we participated in were weekly Auslan lessons with Luke King, which were initiated by the artist-curator and Disorganising collaborator Fayen d’Evie. In the lead up to her exhibition at West Space, d’Evie instituted several accessibility practices that will have a long-term effect on the operations of the institution, including an eight-week Auslan course held over Zoom. Another project that my child and I participated in over Zoom was Nina M. Gibbs’ The Disorganised Manifesto. Part design-research, part workshop, part artwork, participants were assigned letters, numerals, and punctuation marks to design and contribute to an open-source alphabet. These characters formed a communal typeface which was developed into a working font. Through conversation facilitated by Gibbs, participants discussed at length what it means to write a manifesto: the different parts of our lives we wanted to devote more time to, what we’d like to spend less time on, and the desired future for ourselves and the community. This set of desires constituted the manifesto which was published in the typeface and installed as flags in Collingwood in November 2021.38 My son proudly pointed out the letter “T” he designed.

Artist and writer Stephen Palmer argues that organised resistance to arts’ value as “productive work” should take place within the institution. For Palmer, this entails “breaking with the normative condition of being usefully productive to capital accumulation, and the sense that one’s value is based on this capacity.”39 Palmer’s writing reminds me of another series of Disorganising workshops held over Zoom, Composting Our Disorganising, hosted by artist-curator and Disorganising collaborator Jacina Leong 梁玉明. Over two workshops, Leong introduced the metaphor of composting to “to ask what needs to be transformed, what is transforming, individually and collectively, in and through our practices.”40 Through this guiding metaphor, we explored ideas of being in duration, adding nothing new, and being attuned to material changes. We discussed alternative ways to structure the workday: coinciding with circadian rhythms; acknowledging that we give differently each workday; productivity as a violent flattening of time, privilege, and experience. The Disorganising cohort experimented with structuring our workdays to allow for all these degrees of experience. There was permission to step away when overwhelmed with the pandemic or when other life circumstances necessitated. This extended to the artists who participated. As the pandemic and lockdowns wore on, artists were given the option to participate as well as the option to step away, to reschedule, to refuse to produce work and still be paid regardless.

Despite the contradiction of creating more work and operating under the external timeline dictated by Creative Victoria, there were moments of subversion and a refusal to continue to operate under the usual conditions. Early in the projects, through a series of critical writing sessions facilitated by Nguyen and Nhà, we identified the following collective methodologies:

Experimentation; More reading aloud; Peer to peer learning; Time for reflection, debriefing: time for reading and conversation; Acknowledging and gratitude for work that has been done; Reduce the output; Focus on relationships, being together; writing exercises where thoughts can be built upon, eating together/ hospitality.41

These shared methodologies offered a path slow down the pace of work, and while practices such as hospitality, time for reading and conversation did not solve the “busyness,” but the tone and quality of our work changed. Our output become more intentional and reflexive. Our weekly meetings provided an opportunity to reflect and digest; these processes became part of the work. Practices of critical writing followed by reading aloud and listening to each other deepened the relationships between the core cohort. We were working more, but the quality of work was more introspective, thoughtful, critical; I no longer felt as though I was on auto pilot.

Return

In one of the Disorganising critical writing sessions, I wrote:

Disorganising doesn’t come easily to many of us, not when the neoliberal impulse is productivity above all else. But disorganising refuses to be productive. Instead, it is in the realm of the reproductive—how do we work with what we have? How do we make art, make invitations, which are not onerous? How do we care for Country while we work? How are we guided by place and site? How can we add nothing new materially, but instead reproduce, represent, rearticulate the context around us?42

For over nine months, Disorganising collaborators had maintained the “slow building of processes” and the transformation of practices.43 As yet another mandated state-wide lockdown took place in Guling (Orchid Season), the fourth of seven Wurundjeri seasons, Disorganising paused. This sixth lockdown coincided with the birth of my second child and subsequent maternity leave. The moment of “publicness,” where we had planned to share the work of our collaborators in forms such as readings, performances, and workshops at an event scheduled at Collingwood Yards, was postponed. Compared to previous lockdowns, where I scrambled to pivot West Space’s program online and support artists and staff under new and adverse conditions, it felt radical to simply pause the Disorganising program and to not produce. This need for space and to pause was shared across the cohort after almost a year of continually shifting, learning, and unlearning. “Fatigue cannot be scheduled or managed,” states writer Tom Melick. “It comes and goes; it cannot be enclosed between a beginning and an end; it does not acquire value. It is a reduction, an instant, a slowing down.”44 We were guided by artists as to whether they would present their works digitally. Many artists opted not to produce or perform. David Frayne argues that a refusal of work must be “fought on collective and political terms, and not on an individual basis.” As a cohort, we worked to give space for a collective refusal.

When we met again in Buarth Gurru (Grass Flowering Season), on the other side of the lockdown, we launched the Disorganising workbook with readings and performances—a moment of publicness in a project that consisted of so much internal work. After the event, a small group of Disorganising collaborators gathered under the generous green foliage of a plane tree in Collingwood Yards to discuss what to do next. We had awoken that morning to the news that the radical black feminist bell hooks had died, and later that day we were awaiting news of another multi-year funding outcome from Creative Victoria which would determine staffing and salaries for the coming year. This anticipation extended the mode of uncertainty that had defined the last two years. We did not know whether our positions would still exist in 2022. With Nguyen and Nhà concluding their contracts and taking on other projects, would Disorganising continue with new interlocutors? Disorganising seemed too strange and ambiguous a project for an incoming director to inherit. That afternoon, under the plane tree, we tabled the appointment of a salaried artist-in-residence to work between the three organisations and continue the work of Disorganising. Home of the Arts (HOTA) on the Gold Coast had announced the creation of a salaried part time position for artists through their ArtsKeeper initiative. In the case of Disorganising, would a salaried artist position put the onus back on artists to solve the problems of institutions? This leads us to a key question of the project: how to finish Disorganising?

How to finish Disorganising?

The story of perpetual crisis that we in the artworld tell ourselves reinforces the ideology of recovery. In this ideology, as I have argued, precarity is packaged as flexibility and overwork is sold as adaptability and resilience. As we weathered the longue durée of the pandemic with the desire do things differently, Disorganising institutions took part in experiments to change the structure of work. Ultimately, though, Disorganising remained governed by funding bodies, professionalised boards of directors, and other infrastructure that limited the program’s potential radicality. Disorganising was a response to unique conditions, specific to the three organisations and the context of Naarm/ Melbourne in 2020, but it is also translatable, in theory and praxis, to global counterparts who share the desire to change or challenge current labour practices within the art sector.

Learning or unlearning institutional habits, particularly habits of productivity, takes time. Trying to do this work under the conditions of the pandemic—on top of existing programming and with the increased pressure of funding deadlines—contradicted the very nature of Disorganising and ultimately generated more work for its participants. Alternative practices would have refused work all together. The Disorganising program instead explored new ways of working that sprouted from a position of solidarity.

The prefix “dis” is a reversing force—disrupt, disorder, dispute, disassemble, disrepair. Even in name, Disorganising is a refusal, standing against productivity and competition. I hope Disorganising might serve as a model or a pathway forward for other organisations who share the belief that current ways of working can no longer be sustained. Despite the impossibilities of repair (without a complete overhaul of the capitalist system), Disorganising offered glimpses into an alternative way of working and produced speculative possibilities for work. Disorganising resisted easy quantification. Giving artists and collaborators the option to refuse subverted the statistic-driven logic of funding bodies. But how then to evaluate the program? Can we measure its success by the fact that it led to major reassessments of labour, capacity, burnout, productivity, and wellbeing for members of the core cohort? Disorganising attempted to move beyond the self-reflexive to bring about real and lasting change to the participating institutions at a time when radical change felt not only necessary but unavoidable. The short-term changes thus far are on a personal rather than institutional level. Each of the four directors who initiated the project have since left their organisations. They will carry the learnings and lessons of Disorganising through to the next institutions they work at. At an institutional or policy level, the full effects of Disorganising are yet to be felt, but on a personal level, changes to practices of instituting, labouring, and governing are already underway.

-

Maddee Clark, “The Crisis of ‘Decolonising’ The Arts,” Disorganising, published 16 August, 2021,https://disorganising.co/the-crisis-of-decolonising-the-arts, accessed 30 August, 2021. ↩

-

Clark, “The Crisis of ‘Decolonising’ The Arts.” ↩

-

I was the Director of West Space from 2019 to 2022 and worked to initiate the project with Bus Projects and Liquid Architecture (Henceforth, LA). ↩

-

Melbourne’s record-breaking lockdown largely marked the end of state-by-state lockdowns and rendered Australia “open.” ↩

-

Disorganising was initiated by institutional directors Joel Stern, Channon Goodwin, Georgia Hutchinson and Amelia Wallin. Xen Nhà and Lana Nguyen joining the disorganising cohort in February 2021. It expanded to include collaborators Sebastian Henry-Jones, Tamsen Hopkinson, Debris Facility, Liang Luscombe, Leila Doneo Baptist, Benjamin Baker, Ari Tampubolon and Nina Mulhall, in addition to designers Alex Margetic and Zenobia Ahmed, audio producer Jon Thija, copy-editor Sarah Gory, and web developer Dennis Grauel. Participating artists included Cher Tan, Jacina Leong, Timmah Ball, Maddee Clark, Joel Spring & Carol Que, Michelle Nguyen, Food Art Research Network x School of Instituting Otherwise (Madeleine Collie & Meenakshi Thirukode), Torika Bolatagici, Julieta Aranda, 3CR Thursday Breakfast, Ari Tampubolon, Fayen d’Evie, Hoang Tran Nguyen with Tania Cañas and Danny Butt, Nina M. Gibbes, Public Assembly, Tiyan Baker, Yasbelle Kerkow, and Play On. ↩

-

A series of “internal” conversations between Disorganising’s collaborators have recently been published on the digital journal Runway (some interviewees did not wish to be published and these therefore remain “internal”); see http://runway.org.au/, accessed 30 November, 2021. ↩

-

This Disorganising critical writing session was attended by Joel Stern, Channon Goodwin, Xen Nhà, Lana Nguyen, Georgia Hutchinson and Amelia Wallin. ↩

-

This title is an inversion of the phrase “working from home” that characterised working conditions during lockdowns over the course of the pandemic. It is borrowed from disorganising collaborator Julieta Aranda. ↩

-

Elisa Gabbert, “Is compassion fatigue inevitable in an age of 24-hour news?,” The Guardian, 2 August, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/aug/02/is-compassion-fatigue-inevitable-in-an-age-of-24-hour-news, accessed 30 November, 2021; Jane Lee, “Almost one in four women have considered leaving the workforce during COVID, study finds,” The Guardian, 25 May, 2021, <https:// www.abc.net.au/news/2021-05-25/one-in-four-women-considered-leaving-work-after-covid/100163110>, accessed 30 November 2021; Eve Ensler, “Disaster patriarchy: how the pandemic has unleashed a war on women,” The Guardian, 1 June, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2021/jun/01/disaster-patriarchy-how-the-pandemic-has-unleashed-a-war-on-women, accessed 30 November, 2021. ↩

-

At the time of writing, all West Space employee contracts contain a clause stating that the contract can be voided due to changes in funding. ↩

-

Ben Eltham, “We are witnessing a cultural bloodbath in Australia that has been years in the making,” The Guardian, 6 April, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2020/apr/06/we-are-witnessing-a-cultural-bloodbath-in-australia-that-has-been-years-in-the-making, accessed 30 November, 2021. ↩

-

Eltham, “We are witnessing a cultural bloodbath in Australia that has been years in the making.” ↩

-

Eltham, “We are witnessing a cultural bloodbath in Australia that has been years in the making.” ↩

-

Dan Fox, “April to July 2020,” in Art Writing in Crisis, Brad Haylock and Megan Patty, eds. (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2021), 71. ↩

-

This thinking is exemplified by the compendium As radical, as mother, as shelter: What should art institutions do now? The editors asked in response to violence and dissent of the Trump administration in the United States of as shelter: What should art institutions do now? (Brooklyn: Paper Monument, 2018), 3. ↩

-

While a detailed account is outside the scope of this article, it is important to note that in mid-2020 the Black Lives Matter protests swept across the United States. Many institutions became entangled with widespread critique in relation to systemic racists practices, through the Instagram account @ChangeTheMuseum, and open letters to the Guggenheim. See Laura Raikovich’s Culture Strike for further analysis. This movement prompted activists in Australia to draw attention to the alarming number of Aboriginal deaths in custody. ↩

-

See more information on ACCA’s Defining Moments: Australian Exhibition Histories 1968–1999 here: https://acca.melbourne/about/media/defining-moments-australian-exhibition-histories-1968-1999/, accessed 30 November, 2021. ↩

-

See more information on IMA’s Net Positive series here: https://www.ima.org.au/ima-events/net-positive/, accessed 30 November, 2021. ↩

-

For more information on Artist, or Insitution see: http://theartistsinstitute.org/artists/artists-or-institutions/artists-or-institutions/ and https://www.sculpture-center.org/events/13031/artists-or-institutions, accessed 30 November, 2021. For more information on the Bureau of Care see iLiana Fokianaki, “The Bureau of Care: Introductory Notes on the Care-less and the Care-full,” e-flux 113 (November 2020): 1–11. ↩

-

David Pledger, The case for a Universal Basic Income: freeing artists from neo-liberalism, 19 June, 2020, https://www.artshub.com.au/news/opinions-analysis/the-case-for-a-universal-basic-income-freeing-artists-from-neo-liberalism-260583-2367657/, accessed 20 January, 2021. ↩

-

On a micro scale, the West Space team found small ways to reduce pressure, including limiting work hours to 10am-4pm and running all staff check-ins at the beginning and end of each day. However, I can’t help but feel we missed an opportunity to be more radical and experimental with our approach to work. ↩

-

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, Or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Essay is About You,” Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002), 128. ↩

-

Sedgwick, “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, Or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Essay is About You,” 146. ↩

-

Maggie Nelson, On Freedom: Four Songs of Care and Constraint (London: Jonathon Cape, 2021), 26. ↩

-

Lauren Carrol Harris, “The Arts Crisis and the Colonial Cringe,” Kill Your Darlings, published 15 October, 2020, https://www.killyourdarlings.com.au/article/the-arts-crisis-and-the-colonial-cringe/, accessed 20 December, 2021. ↩

-

See the NAVA senate inquiry <https://visualarts.net.au/advocacy/covid-19/navas-submission-covid-19-senate- inquiry/>, accessed 30 November, 2021. ↩

-

See Esther Anatolitis, “We Need to Stop Punishing Artists: Their Creative Thinking Will Help Us Out of This Crisis,” The Guardian, 28 July, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2020/jul/28/we-need-to-stop-punishing-artists-their-creative-thinking-will-help-us-out-of-this-crisis; see also: “‘If Our Government Wants Cultural Life to Return, It Must Act Now’: An Open Letter From Australia’s Arts Industry,” The Guardian, 24 April, 2020, <https://www.theguardian.com/ australia-news/2020/apr/24/if-our-government-wants-cultural-life-to-return-it-must-act-now-an-open-letter-from-australias-arts-industry>, accessed 13 December, 2021. ↩

-

See Alison Pennington and Ben Eltham, “Creativity in crisis: rebooting Australia’s arts and entertainment sector after COVID,” Centre For Future Work, 26 July, 2021, https://apo.org.au/node/313299 and “Put Creative Workers to Work,” https://www.creativeworkers.net/, accessed 30 November, 2021. ↩

-

Stephen Palmer, “Art in Crisis: Resilience, Recovery, Reproduction,” Un Magazine 15 vol. 1 (2021): 26–31. ↩

-

Benjamin Law, ‘In times of crisis, we turn to the arts. Now the arts is in crisis – and Scott Morrison is silent’, The Guardian, 27 March 2020, <https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2020/mar/27/in-times-of-crisis-we-turn-to- the-arts-now-the-arts-is-in-crisis-and-the-federal-government-is-missing-in-action>, accessed 20 January, 2022. ↩

-

For further writing on COVID and artist productivity see Audrey Schmidt, “Lost In The Feed/Translation,” Memo Review, published 11 July, 2020, https://memoreview.net/reviews/lost-in-the-feed-translation-by-audrey-schmidt, accessed 30 August, 2021. ↩

-

Nika Dubrovsky and David Graeber, “Another Art World, Part 1: Art Communism and Artificial Scarcity,” e-flux 102 (September 2019): 1–9. ↩

-

A welcomed alternative was private funding from the Sidney Myer Fund which requested that artists simply submit a URL to a website in order to gain A$1,000 funds, see https://www.myerfoundation.org.au/news-story/national-assistance-program-for-the-arts, 7 May, 2020. ↩

-

It is worth noting that many artists received their greatest level of support through JobKeeper, which did not require any output and thus makes a clear argument for a Universal Basic Income as a way of meaningfully supporting artists. ↩

-

David Frayne, The Theory and Practice of Resistance to Work (London: Zed Books, 2015), 266. ↩

-

Disorganising newsletter, co-authored by Channon Goodwin, Georgia Hutchinson, Joel Stern and Amelia Wallin, distributed simultaneously across West Space, Bus Projects, and Liquid Architecture’s mailing lists, 18 November, 2020. ↩

-

Disorganising newsletter, written by Xen Nhà, with support from Sarah Gory and the teams at West Space, Liquid Architecture, and Bus Projects, distributed simultaneously across West Space, Bus Projects, and Liquid Architecture’s mailing lists, 24 August, 2021. ↩

-

This coincided with the launch of Disorganising’s workbook. ↩

-

Palmer, “Art in Crisis: Resilience, Recovery, Reproduction,” 26–31. ↩

-

Jacina Leong “Composting our disorganising,” Disorganising, 19, August, 2021, https://disorganising.co/composing-our-disorganising, accessed 30, November 2021. ↩

-

Disorganising critical writing session facilitated Lana Nguyen and Xen Nhà, 3 June, 2021. ↩

-

Disorganising critical writing session facilitated Lana Nguyen and Xen Nhà, 1 April, 2021 ↩

-

The “slow building of processes” is Lana’s phrase, taken from the Disorganising workbook. The nine months of disorganising coincided almost perfectly with the gestation of my second child, from interviewing Xen and Lana while unwell with morning sickness to attending workshops full term. The two are interlinked permanently in my mind. ↩

-

Tom Melick, A Little History of Fatigue (Sydney: Rosa Press 2021), 15. ↩

Amelia Wallin is a curator and writer, living on Dja Dja Wurrung land. As a curator she has conceived and delivered large scale commissions for multidisciplinary art centres, biennales, and independent spaces across Australia and the USA. Her writing and critism has been widely published. Amelia has been involved in multiple artist-led initiatives in Sydney and Melbourne as founder, director and curator. This experience in shaping artistic production carries through her practice as commitment and investment in the alternative possibilities of art institutions. Her current PhD research at Monash University makes explicit this interest, by interrogating the future of institutions and their reparative potential.

Bibliography

- Anatolitis, Esther. “We Need to Stop Punishing Artists: Their Creative Thinking Will Help Us Out of This Crisis.” The Guardian, July 28, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2020/jul/28/we-need-to-stop-punishing-artists-their-creative-thinking-will-help-us-out-of-this-crisis, accessed 30 November, 2021.

- Carrol Harris, Lauren. “The Arts Crisis and the Colonial Cringe.” Kill Your Darlings. Published 15 October 15, 2020. https://www.killyourdarlings.com.au/article/the-arts-crisis-and-the-colonial-cringe/, accessed 30 November, 2021.

- Clark, Maddee. “The Crisis of ‘Decolonising’ The Arts.” Disorganising, published 16 August, 2021, https://disorganising.co/the-crisis-of-decolonising-the-arts, accessed 30 November, 2021.

- Dowling, Emma. The Care Crisis: What Caused It and How Can We End It? London: Verso Books, 2022.

- Dubrovsky, Nika and David Graeber. “Another Art World, Part 1: Art Communism and Artificial Scarcity.” e-flux 102 (September 2019): 1-9.

- Eltham, Ben. “We are witnessing a cultural bloodbath in Australia that has been years in the making.” The Guardian, April 6 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2020/apr/06/we-are-witnessing-a-cultural-bloodbath-in-australia-that-has-been-years-in-the-making, accessed 30 November, 2021.

- Frayne, David. The Refusal of Work: The Theory and Practice of Resistance to Work. London: Zed Books, 2015.

- Fokianaki, iLiana. “The Bureau of Care: Introductory Notes on the Care-less and the Care-full,” e-flux 113 (November 2020): 1-11.

- Fox, Dan. “April to July 2020.” In Art Writing in Crisis edited by Brad Haylock and Megan Patty, 55-74. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 202.

- Gabbert, Jane. “Is compassion fatigue inevitable in an age of 24-hour news?” The Guardian, 2 August, 2018. <http s://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/aug/02/is-compassion-fatigue-inevitable-in-an-age-of-24-hour-news>, accessed 30 November, 2021.

- Kimitch, Benjamin Akio. “Commensurate with Experience.” Movement Research Performance Journal 55 (March 2021): 30-35.

- La Berge, Leigh Claire. Wages Against Artwork: Decommodified Labor and the Claims of Socially Engaged Art. North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2019.

- Law, Benjamin. “In times of crisis, we turn to the arts. Now the arts is in crisis — and Scott Morrison is silent.” The Guardian, 26 March, 2020. <https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2020/mar/27/in-times-of-crisis-we-turn-to- the-arts- now-the-arts-is-in-crisis-and-the-federal-government-is-missing-in-action>, accessed 30 November, 2021.

- Lee, Jane. “Almost one in four women have considered leaving the workforce during COVID, study finds.” The Guardian, 25 May, 2021,(http://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-05-25/one-in-four-%09women-considered-%20leaving-work-after-covid/100163110), accessed 30 November, 2021.

- Leong, Jacina. “Composting our disorganising.” Disorganising, 19 August, 2021. https://disorganising.co/composing-our-disorganising, accessed 30 November, 2021.

- Melick, Tom. A Little History of Fatigue. Sydney: Rosa Press, 2021.

- Nelson, Maggie. On Freedom: Four Songs of Care and Constraint. London: Jonathon Cape, 2021.

- Palmer, Stephen. “Art in Crisis: Resilience, Recovery, Reproduction.” Un Magazine 15 vol. 1 (2021): 26-31.

- Pennington, Alison and Ben Eltham. “Creativity in crisis: rebooting Australia’s arts and entertainment sector after COVID.” Centre For Future Work, published 26 July, 2021. https://apo.org.au/node/313299, accessed 30 November, 2021.

- Petrovich, Dushko and, Roger White. As radical, as mother, as shelter: What should art institutions do now? Brooklyn: Paper Monument, 2018.

- Pledger, David. “The case for a Universal Basic Income: freeing artists from neo-liberalism.” ArtsHub. Published 19 June, 2020. https://www.artshub.com.au/news/opinions-analysis/the-case-for-a-universal-basic-income-freeing-artists-from-neo-liberalism-260583-2367657/, accessed 30 November, 2021.

- Raicovich, Laura. Culture Strike Art and Museums in an Age of Protest, London: Verso Books, 2021.

- Schmidt, Audrey. “Lost In The Feed/Translation.” Memo Review. Published 11 July, 2020. https://memoreview.net/reviews/lost-in-the-feed-translation-by-audrey-schmidt, accessed 30 November, 2021.

- Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity. Durham: Duke University Press, 2002.