Fugitive Abstraction Gordon Bennett’s Stripe Series

The mimetic skills that protect the vagrancy of the one passing through cast a veil over his or her identity.

Paul Carter, Meeting Place1

Gordon Bennett’s abstract Stripe series seeks to expose and repel the role of identity in the interpretation of his work. Bennett turned to abstraction to re-engage with the problem of modernist painting and at the same time escape the entrapment of his work by critics operating in the framework of racial identity. To see the solution that Bennett proposes to the modernist problem of painting in the early twenty-first century requires casting back through his oeuvre and critical reception. In this paper, I show that his work has been misapprehended through the restrictive lens of identity. I evaluate the critical reception of Bennett’s abstracts in the context of the broader incorporation of his work in the framework of post-colonial appropriation. I then turn to the direct source of Bennett’s Number Nine and other abstract works, Frank Stella, and consider the terms of Michael Fried’s embrace of Stella. I argue that these terms continue to provide a compelling framework within which to interpret Bennett’s achievement in the Stripe series.

Bennett began the Stripe series in 2003, along with his equally aversive “John Citizen” series, Interiors, which enacted in performative disidentification what the Stripe series does by formal abstraction. Bennett’s Number Nine (2008) is a striking painting that wrestles with fundamental dynamics in modernist painting by engaging the work of Stella and his critical celebration by Fried. Bennett exploits this lineage to complex effect in Number Nine, playing with the polyvalent significance of blackness in modernist painting as well as using lines to provoke questions of freedom and constraint. The dynamic of freedom and constraint playing out on the surface of the paintings continues to compel conviction in the hands of Bennett, denying the entrapments of identity and inviting us to reconsider the terms upon which we appreciate Bennett’s entire oeuvre. This claim takes up and extends the early reception of Bennett’s abstract, which, as Ian McLean writes, identified the project of “escaping an identity politics that paradoxically dispossess a people (including himself) by Aboriginalising them.”2 Citing Darby English’s How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness, Maggie Nelson has recently noted that “it remains a challenge to shed the habit of predictable, reductive, identity-based responses,” such as those that treat all abstract art by Black artists as “the cryptic articulation of fierce racial pride awaiting disencryption.”3 With the abstract Stripe series, Bennett invites the viewer to abandon the narcissistic project of disencryption, which obscures the painting itself, and restore to prominence the aesthetic qualities of the painting.

My argument is that the abstracts expose the racialisation involved in the critical reception of Bennett and at the same time avert its imposition on these paintings. It is the paintings’ capacity, which inheres in their specific aesthetic qualities, to both expose and avert that I am calling “fugitive abstraction.”4 Throughout his career, Bennett sought to create “fields of disturbance which would necessitate re-reading the image,” and the Stripe series constitutes his last attempt to this effect.5 They arrest and repel the racializing gaze and return it to the revelatory act of seeing paint on canvas. The paintings offer, literally, lines of capture and freedom. In so doing, they engage with the problematic described by Fried in his “Three American Painters” catalogue essay in 1965, in which he elaborates the achievements of the modernist painters Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, and most importantly, Stella. Establishing a frame that he will apply to all three, Fried writes of Noland that he was “as much concerned with freedom as with formal constraint.”6 Interest in Fried’s work has been rekindled recently for various purposes.7 I light upon Fried because he pugnaciously asserts particular aesthetic features in modernist painting in a way that helps articulate the challenge taken up in Bennett’s abstract series.8

Bennett’s Modernism via Fried and Adorno

For Fried, the best modernist painting responds to its predecessors, taking up the problems posed in them and renewing our conviction that the project of painting is worth pursuing in the face of the near total imposition of instrumental, economic rationality on all parts of life.9 Fried’s and, as I will show, Theodor Adorno’s, modernist commitments intersect with Bennett’s insistence on the primacy of freedom as an “underlying drive” in the context of historical and institutional alienation.10 One important counterpoint to Bennett’s artistic project emerges from his account of working as a Telecom linesman between 1975 and 1985 (the year of the Queensland SEQEB strike),11 after which he describes the loss of “dignity and self-esteem,” asking, “what do you do if the values promised for your labour are not forthcoming; you do not feel happiness, satisfaction, or great comfort in the sacrifice?”12 For Bennett, as Fried and Adorno’s post-Kantian modernism can articulate, artistic work and aesthetic experience represents a sphere of freedom within colonial, capitalist modernity. Vital here too is Bennett’s comment that “to be free we must be able to question the ways our history defines us.”13

Fried defends the work of his cadre of artists by attending to “exemplary act[s] of radical criticism of [their] own best work,” which opens “a wholly new dimension of formal and expressive freedom for [their] art.”14 I think something similar is going on in Bennett’s Stripe series. Bennett not only takes up the abiding concerns of his previous work and subjects them to self-criticism but also interrogates and challenges the critical vocabulary developed for his work.15 Fried is not alone in his assessment of the relationship between the internal and external dynamics of modernist art. Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory provides a useful point of comparison. For Adorno, art’s past, its own monuments, have “refuge only at the vanguard of the new: in the gaps, not in the continuity.”16 Instances of genuine art consist in discovering solutions to problems posed by the best art of the past, as Bennett found solutions to problems posed in the paintings of Stella (as well as their respective critical receptions).

Moreover, Adorno allows us to consider the interchange between art and political and social reality. Defending a version of the “autonomy of art” thesis, Adorno argues that it is

only by virtue of separation from empirical reality, which sanctions art to model the relation of the whole and the part according to the work’s own need, does the artwork achieve a heightened order of existence. Artworks are afterimages of empirical life insofar as they help the latter to what is denied them outside their own sphere and thereby free it from that to which they are condemned by reified external experience.17

The complexity of Bennett’s abstracts is that they assert such a separation from both his previous work and its critical reception and simultaneously respond to it. They contain a power of exposure—of the racialized critical apparatus that sets out to capture his work—to the extent that they are separate from the determining empirical reality,18 and have a power of revelation to the extent that they are internally coherent. Number Nine’s dense hermeticism appears to seal it from the world, and yet, as Adorno notes, the artwork is

related to the world by the principle that contrasts it with the world…The synthesis is achieved by means of the artwork is not simply forced on its elements…This unites the aesthetic element of form with noncoercion.19

Number Nine invites and rebounds facile interpretations, finding a space of freedom within the strictly delimited frame of the painting, the shape of which is forcefully echoed by Bennett’s lines.

Number Nine consists of two panels symmetrically lined with an emanating sequence of offset rectangles. The panels echo each other with a vibratory quality that both disrupts and intensifies the experience of viewing. The lines, in contrast to Stella’s restricted palate, shift from metallic gold to black at the point at which the corners of the rectangle almost, but do not, touch the edge of the canvas. Slight smudges of colour butterfly outwards at a diagonal, but the force of the painting is concentrated not only by the lines but also by the angles created at the corners of each rectangle, which dissect the canvas upwards and across. This concentration of force creates an eerie, turbulent space that both entices and disturbs the contemplative experience typical of the bourgeois beholder.20 Absorption oscillates with reflection prompted yet withheld by the very slight metallic quality (in contrast to Stella’s more muted tone). The effect of viewing the work is a kind of radiating shimmer reminiscent of an optical illusion, suggesting that something is hidden. Yet nothing is hidden. The lines in Number Nine are given, following Bennett, an “existential” quality that draws a link between the act of painting and the experience of beholding the painting.21

Critical Capture and Bennett’s Solution

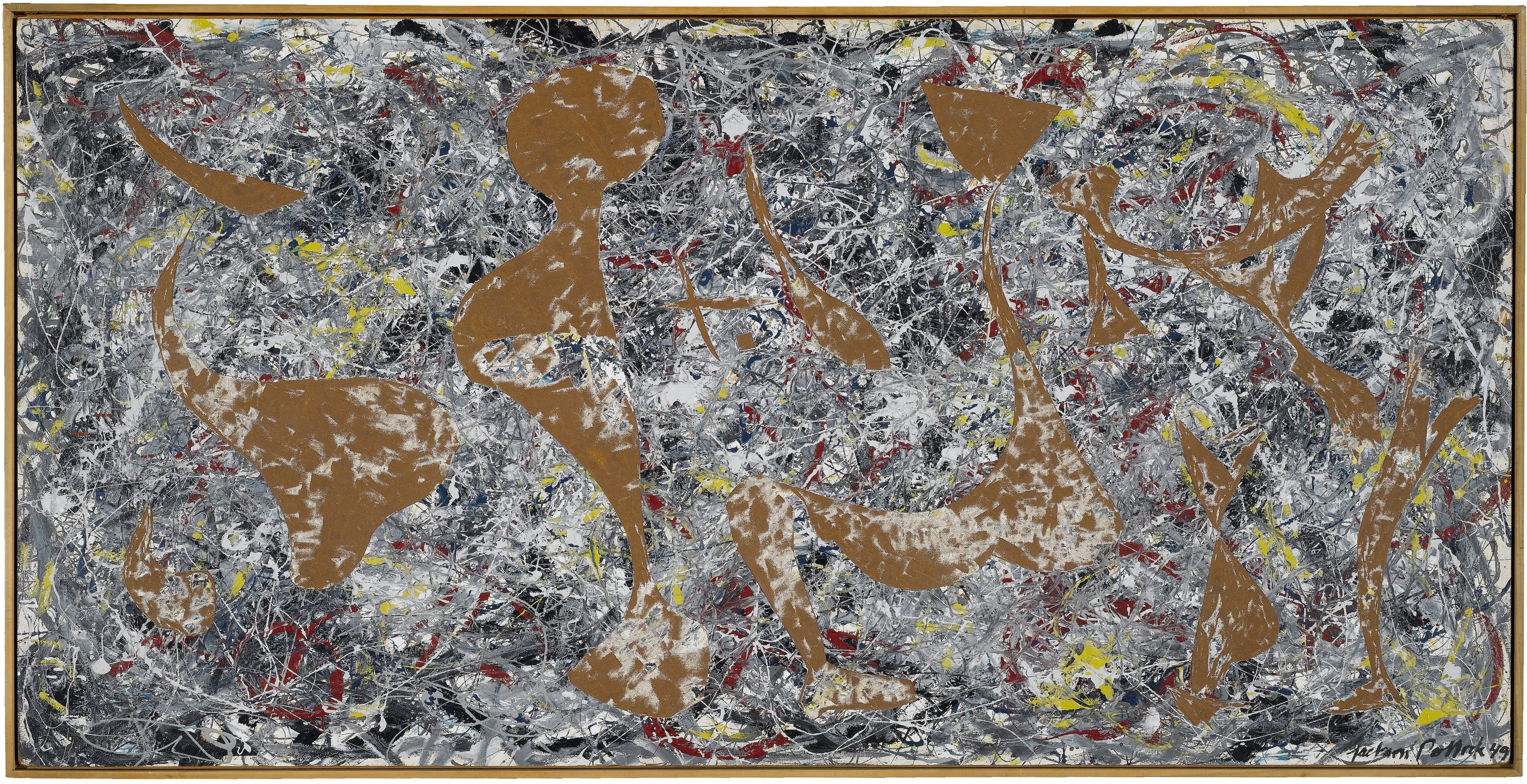

The abstract series can usefully be interpreted as a solution to the problems Bennett was facing as an artist after his early and mid-career successes. Far from definitive, I suggest the term “solution” as provisional, just as Fried does in his assessment of Frank Stella’s career. Fried proposes that Stella, like many mid-century painters including Jackson Pollock (who numbered his paintings22) and Robert Rauschenberg, worked in series “in an attempt to demonstrate—to Stella himself as well as to the beholder—both the perfectibility and the flexibility of the solution in question.”23 Fried adds that the series is “one of modernist painting’s chief defenses against the risk of misinterpretation.”24 Bennett was intimately familiar with these artists, having incorporated Pollock’s distinctive style into some of his best-known works such as Possession Island (1991) and Death of the Ahistorical Subject (Vertigo) (1993).25

This problem was particularly acute for Bennett, who, as Kelly Gellatly writes was “physically and emotionally exhausted by his postcolonial project [from which he] sought a form of release.”26 Similarly, Zara Stanhope posits that “from 2003, Bennett would take a reprieve from overt sociopolitical considerations by allowing grids and stripes to dominate in non-representational paintings,” as though politics requires representation, or as if “sociopolitical considerations” were a burden on the paintings.27 Stanhope implicitly deflects the political force of non-representational painting in Bennett’s oeuvre, despite it being a feature throughout. For Stanhope, camouflage works as a form of retreat rather than as a strategy of aversion and exposure consistent with aesthetic and political freedom.28

In “The Manifest Toe,” Bennett’s most extensive piece of writing, he states that one of his central concerns is to “be free to question the way power is exercised, disputing claims to domination…To be free we must be able to question the ways our own history defines us.”29 In her assessment of the abstract series, Gellatly refers to the “painterly quality of the surface” as a way for the artist to be “everywhere and nowhere in the paintings. This [is a] denial of information—in effect a refusal to ‘communicate.’”30 Gellatly rather patronisingly refers to the abstracts as “a brave ‘front,’” before re-connecting them to

precedents drawn from the history of Australian and international art. So while Bennett may have attempted, in recent years, to disconnect from the politics of his earlier practice, there is also a sense within these paintings, of the impossibility of such a task. For given the artist’s own history of “engagement,” these works are not considered “simple” abstract paintings, but abstract paintings by “Gordon Bennett”; coloured, or even tainted by, the history, concerns and associations of the artist’s earlier work.31

Gellatly’s statement condemns the abstracts to a further “engagement” in what Bennett had found so dissatisfying, evident in his abiding concern with freedom and challenging history, which he argues have been extant in “all of my work.”32 Gellatly deploys Bennett’s name in inverted commas as a sort of weight, a kind of trap the type of which was so readily used to explain his early work that drew on Pollock, Mondrian, Margaret Preston, and others.33 Remarkable too is the language with which Gellatly choses to confine Bennett: “coloured, or even tainted” by history, as though it were not in fact the history that were coloured from the beginning. Bennett himself proposes the “overtly ‘abstract’ work [as] a way of distancing myself from the work so people can see me as separate from it.”34 With the “fugitive” abstracts, he attempts to avoid precisely the trap laid for him by Gellatly and others. Bennett’s situation recalls what Fried wrote about Stella, Olitski and Noland, that “it is one of the most important facts about the contemporary situation in the visual arts that the fundamental character of the new art has not been understood.”35 Addressing the source of Number Nine and other works in the series, Bennett describes the weight of identity and his search for a fugitive strategy: “The question of my desire to circumvent aboriginalisation by shifting to a more internationalist arena is true, but I guess I failed in that respect…People will always bring their preconceptions to the work.”36

Appropriation and Historicism: Two Entrapments

There is another reason for addressing Fried’s engagement with Stella in the context of Bennett’s Number Nine, namely that for Bennett, the affinity with Stella is not an “appropriation, which I understand as the use of another artist’s work directly, rather than as a starting/reference point of departure.”37 Similarly, Fried argues that modernist painters cite the history of painting “not as an act of piety towards the past but as a source of value in the present and future.”38 This positions the abstracts as solutions to a problem posed by Stella in his paintings, and it is one Fried identified with the problem of freedom and constraint.39 Bennett sought to distance the abstracts from the tradition of “appropriation art” that sought a subversive or ironic response to colonial iconography, in Butler’s words, “remaking work from his own ‘excluded’ subject position.”40 Numerous critical assessments of Bennett’s work attest to the central conceit of appropriation in the official interpretation of his work. While it has a basis in his work, especially during early periods, the persistence of appropriation confines him to a derivative postmodernism and risks misapprehending the deconstructive, disintegrative force of appropriation.41 Bennett’s rejection of “appropriation” as a description of his relationship to the history of painting questions much of the previous critical literature on Bennett, which casts him as an ironic, post-colonial appropriator of the Western canon.42 Moreover, this framing captures Bennett in a tragic dilemma “in which Bennett could no sooner offer a re-reading of works than this re-reading is already seen in them, in which he could no sooner offer an alternative to tradition than tradition is already seen to be this alternative.”43 This turns the screw too quickly though, presuming a seamless mechanical assimilation of new work into a tradition that remains unmodified by such an inclusion.44 If there are lessons to be learned from post-colonial writing on the subject of identity, one is that the colonised subject does not leave the coloniser unscathed in their forced assimilation. The mimetic act of assimilation disturbs and de-stabilises the identity of coloniser and colonised alike.45

Misrecognition of the de-stabilisation that Bennett creates means that reading the abstracts as part of a universal, modernist project risks turning it into a cipher for a false universalism of whiteness. Bennett, on this account, would play only a legitimising role to “discursively authorise,” as Aileen Moreton-Robinson clearly marks, the perpetuation of racist “epistemic violence.”46 Bennett’s aversion to the limiting racialised framework used to interpellate his work should not be mistaken as authorising the ignorance of racist, colonial history and politics, nor its role in shaping the tradition of modernism. It is essential that the abstracts, following Bennett’s previous work, force us to confront the act of stealing within the modernist canon. The reconfiguration of the canon suggested by Butler occurs only on condition of the visibility of this act, which prevents its seamless re-entry into the annals of modernism.47 This is why it is important to emphasise the exposure of the racializing gaze and the confinement it entails, formally, through the painting itself. And simultaneously, insofar as the exposure becomes visible through the act of beholding the painting, we are invited to affirm their aesthetic beauty in a way that averts the limited frame of identity. The accomplishment of the Stripe series is that it demands both through artistic and purely aesthetic means alone, within a context Bennett can take for granted and so challenge. Number Nine, for instance, succeeds in a context designed to undermine its aesthetic significance, through (rather than despite) the process of confrontation and exposure it forces the beholder to undergo and, in the absence of that context, succeeds just the same.

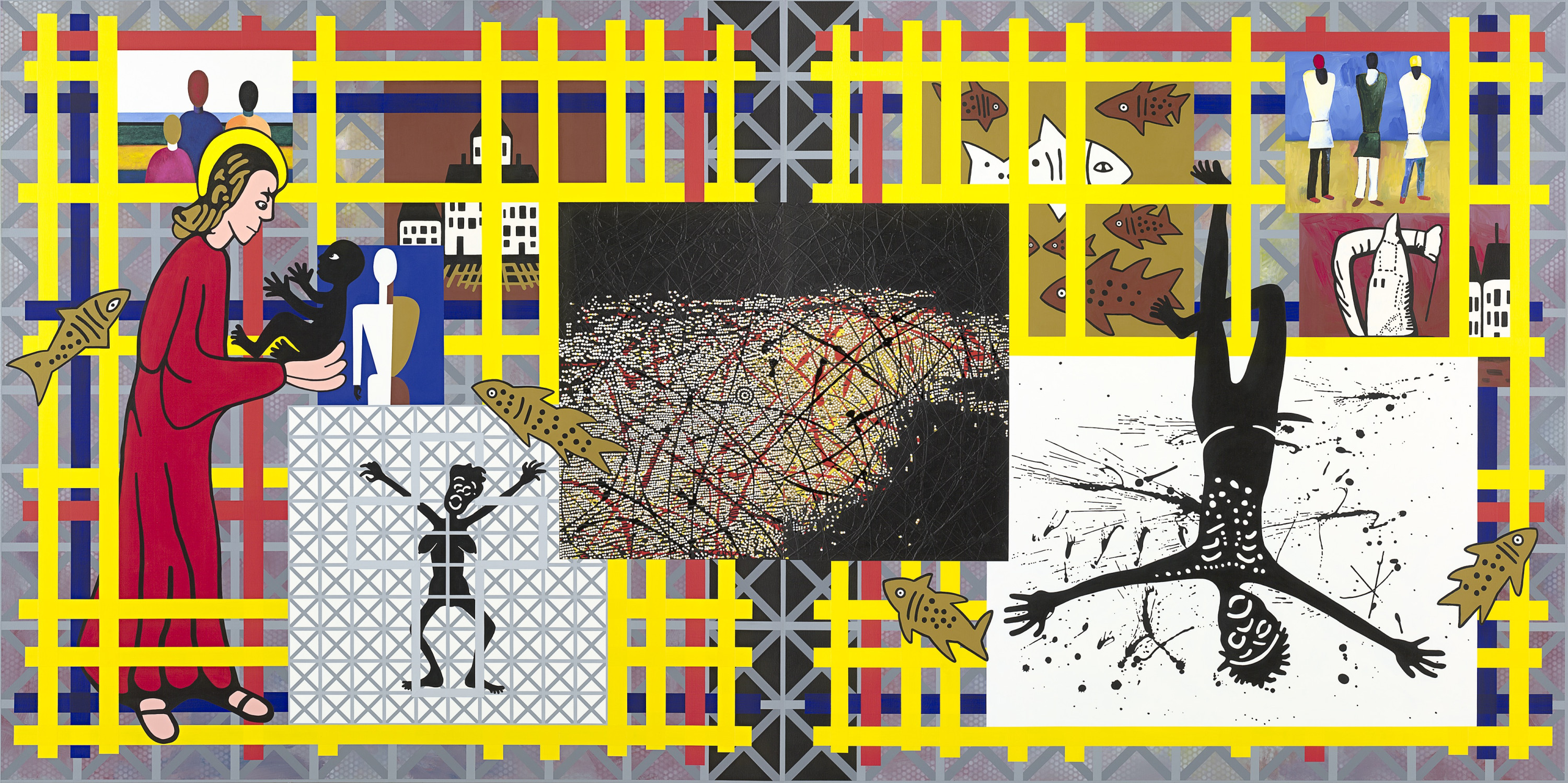

McLean identified in response to early estimations of Bennett’s work an “anxiety” among viewers, who “are troubled…by the gaps between the re-arrangements and constellations of signs which they fill with their own expectations: Gordon Bennett, angry young Aboriginal artist appealing to the guilt of the colonisers.”48 Bennett discovered that challenging fixed conceptions of the relationship between painting, identity, and politics by mocking and exposing racist colonial tropes could be folded into the historicist narrative of what his critics called the “mise-en-scene of identity.”49 Critics and art historians identified Bennett as “subversive” in Anne M. Wagner’s sense of offering “a diversion from a more careful consideration of an art determined to be seen to make a difference.”50 Techniques like appropriation were seen to serve extra-aesthetic considerations like the (de-)construction of identity.51 For example, Stanhope develops the view that “reproduction and appropriation enabled the reinstatement of an Indigenous presence in history…facilitating the refutation of imposed concepts such as the ‘noble savage.’”52 Such a conceptual proposition is, to some extent, supported by Bennett’s statement that in Possession Island (1991)

The black person enters the space of painting (a European space) from behind…He enters the space of European representation in his new role or he enters not at all…His black skin is associated/identified with a black rectangle, an abstraction. The rectangle is a kind of void, as is the black body in a sense, to be filled with European “knowledge” of the world.53

While Bennett implies the entry of the black figure into historical space and knowledge, the conditions of entry are highly ambivalent, namely through the black rectangle, “an abstraction.”

If Bennett’s idiom developed by retrieving buried Indigenous sources of modernism, as Butler has suggested, they are not historicised within an existing canon but actively synthetised in connection with pillars of European modernism. Red, yellow, and black work as references to both Malevich’s Suprematist compositions and the Aboriginal flag, asserting neither yet forming a consistent aesthetic statement.54 In an example of the risk of mis-reading this aesthetic statement for an assertion of identity, Toni Ross interprets Bennett’s early Triptych: Requiem, Of Grandeur, Empire (1989) as a representation of the confrontation between “the generic template of Western landscape painting” and “an alternative, Indigenous Australian pictorial idiom.”55 Ross writes that “appropriation is employed to picture alternative conceptions of subjective agency, history and nation to those colonialist formations that [Bennett’s] paintings had previously interrogated.”56 Instead, Ross proposes the challenge set forth by Juan Davila in refusing the terms of identity by inventing “zones of silence against the current dictatorship of the masks of identity” to make space for “things that cannot be named.”57 Bennett’s abstracts avert this false dichotomy, numbering instead of naming and painting rather than depicting. Ross correctly attacks the historicist account of Bennett that integrates every subversion as a sign of the construction of identity.58 But the insistence on the subject (however lacking, castrated, desiring, or unrepresentable59) as the key interpretative device is misleading, and unwittingly repeats the terms that Bennett found constrained him as an artist.

Identity, Blackness, and the Colonial Gaze

The casting of Bennett as constantly and necessarily in dialogue with “his status as an Aboriginal man within a European culture” as part of “the endless self-critique of Europe” drastically neglects his attempt to reject such framing, as it does the aesthetic quality of his work.60 As English writes in How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness, “To acknowledge such viewer complicity is simultaneously to recognise that this viewpoint is often grounded outside the work of art itself and beyond the profound intentions of the artist.”61 He argues that

we simply cannot see black artists’ work until we throw it into relief against the transformations it undergoes in our inevitably social involvement with it…It will require an alertness to the constructed discursive and institutional, note innate, aspect of the link between artists and idioms. And paradoxically as it may seem, this alertness has to be cultivated partly through the eyes.62

Such schemas as “Aboriginal” or “Indigenous” art overlay any actual experience of the work, colouring it “black art,” in English’s terms, marked by the nebulous quality of “blackness” which serves to “provide the art with a principle of intelligibility.”63 This principle is applied to the work, in which we “read” certain signs as “racial information.”64 By this process, identity is “secured” and the art explained apart from any consideration of its material, aesthetic qualities.

English turns to Frantz Fanon to articulate a politics that starts not from a secure identity but from “the fundamental instability of the kind of blackness that is imagined to provide a visual gift to its perceiver and stable habitus to its inhabitant.”65 These terms echo Bennett’s strategies for disrupting the frame of identity. Bennett aimed to “create a turbulence in the complacent sense of identification…a kind of chaos of identification where new possibilities for signification in representation can arise.”66 English pursues the work of artists like William Pope.L whose practice makes a “commitment to dispossession as an essential component of identity formation…we are faced with a politics of obscurity, as when one obscures one’s political role so as to better articulate it.”67 Bennett has similar commitments, which develop an aesthetic solution in response to the continued problem of constraint imposed on his work. The artistic strategy Bennett employs in the Stripe series encourages us to cultivate alertness by understanding the phenomenological richness of the paintings as a corrosive agent on the layers of reception that have limited our ability to see the paintings with our eyes. English helps remind us to avoid what he calls the “unmodified perpetuation” of a fixed conceptualisation of artists’ work.68

We should revise our understanding of the art of appropriation and Bennett’s relationship to it in light of both his statements about appropriation and his later work with the abstracts. By stripping away the figurative or narrative elements in his work, Bennett refocuses our attention on the aesthetic dimension. This does not mean he abandons or withdraws from politics; rather, we are forced or compelled to re-figure the politics of his work in light of his fugitive abstracts.69 Bennett’s interventions in the history of colonial art did not, then, serve to assert an Aboriginal perspective that could be included or integrated but rather “replicated or even parodied the selective process of a teleological history perspective.”70 Similarly, his appropriations of Pollock did not simply add to the progressive narrative of modern art, dating it further back as many have noted in Navaho ground painting, but actively sought to undermine any progressive or teleological narrative of modernism.71 Bennett seeks to assert a modernism in which Stella and Emily Kame Kngwarreye could attain vital significance in his work. Yet he laments that “if I had put her name forward before Stella’s I wouldn’t be [seen as] circumventing aboriginalisation.”72 Bennett’s work with the problem posed by Pollock is a useful precursor to his reference to Stella, since in Fried’s more dialectical art history, Stella is a successor to the problems posed by Pollock too.73 The conditions of aesthetic achievement are historical and respond to problems posed by predecessors, yet it is not progressive since these achievements do not disappear, nor are they incorporated into a bland assertion of historical development of progressive accumulation. Indeed, the patina of identity accumulates to obscure the painting, leading to Bennett’s adoption of abstraction to expose and avert the suppressive, dampening effects of this integration.

Beyond Racial Vision: Exposure and Aversion

It is only when we see Bennett’s work as a positive assertion of an identity that it becomes trapped in an ironic, self-defeating circle of integration. The abstracts allow us to challenge this view, refusing to posit an identity in appreciating the beauty of the works. Bennett explicitly denies the assertion that

the “work invokes a sense of Aboriginal visual tradition” [as] an example of imposing cultural baggage. It’s in the eye of the beholder…Cultural baggage is a problem in that one can’t clearly see past one’s expectations. If a person expects an “Aboriginal” artist to make Aboriginal art then that is what they will find, or read into the work.74

Racial vision obscures painting.75 Bennett’s turn to the tradition of painting embodied by Pollock and Stella is consistent with Fried’s consideration that their works “defy being read.”76 Fried’s description of what he sees in Pollock’s paintings such as Cut Out (c.1948–1950) is remarkable: “More than anything, it is like a kind of blind spot, or defect in our visual apparatus; it is like part of our retina is destroyed or for some reason not registering the visual field over a certain area.”77 Similarly, the “sequence of figures in Out of the Web (1949) are almost as hard to see…as a sequence of blind spots would be. They seem to be on the verge of dancing off the visual field or of dissolving into it and into each other as we try and look at them.”78 These remarks could be re-worked as descriptions of the figures that emerge from Bennett’s lines in his references to Mondrian and de Stijl, such as Home décor (Preston + de Stijl = Citizen) Dance the boogieman blues (1997).79 Rather than asserting their existence within the line, however, we could equally and perhaps more consistently read these figures as Bennett’s archaeological excavation of what we already read in the line, and the rendering explicit of racial vision in order to escape it.

With the abstracts, Bennett had exhausted this strategy of making racial vision explicit. It had proved impossible to convince critics that it was not simply a testimony of an “experience marked by the pain of racial abuse.”80 In other words, critics mistake concern with questions of identity (and artists’ entrapment or entanglement in them) with affirmation of identity.81 Bennett insists that Aboriginality is “not a life raft for me. It remains too problematical to identify with and leave unquestioned,” but that it reflects that he “did want to explore

‘Aboriginality’ however, and it is a subject of my work as much as colonialism and the narratives that frame it, and the language that has consistently framed me.”82 The experience of racialisation is brought into the frame here in order to trouble rather than affirm his identity.83 As Nicholas Thomas writes, Bennett “avoids affirming an objectified Aboriginal culture in opposition to colonial ideologies, and instead proceeds by disrupting colonial representations themselves, by recasting them in various ways, and by insisting on the presence of racism and violence within them.”84 To return to Adorno, “what the reified artwork is no longer able to say is replaced by the beholder with the standardised echo of himself, to which he harkens.”85 Racial vision is a narcissistic pathology that cannot help but see itself in the painting, and so produces a blind spot that occludes us from appreciating the painting itself.86

The Beholder and Experience

It is the experience of the beholder, rather than the experience (of pain, injury, trauma, or abuse) of the artist that Bennett is trying to restore to prominence in criticism.87 The Stripe series offers an abundance of visual pleasure and demonstrates that Bennett is committed to the visibility of the painting, as against the “privacy” of other recent artists’ pursuit of secession, or the “unrepresentability” fashionable in the deconstruction of identity. However, Bennett also subtly undermines the complacent “centrality” of the viewer “to an ordered array of phenomenon which is rendered completely visible in a compressed symbolic configuration,” which he labels “an ideological fabrication.”88 As McLean noted of earlier periods in Bennett’s work, “he forces the viewer’s hand by demanding from them a further interpretation. That is, Bennett’s simultaneous readings of various paintings mobilise a field of ambiguity which only the viewer can resolve, or at least negotiate and navigate… They are troubled by the implied meta-text of Bennett’s paintings, by the gaps between the re-arrangement and constellations which they fill with their own expectations.”89 This phenomena, characteristic of the narcissistic colonial gaze, is similar to—but not identical with—the diagnosis offered by Fried of the position of the beholder with respect to “objecthood.”90 The viewer of a minimalist object, Fried proposed in his infamous essay, is “included” in the situation; “the situation itself belongs to the beholder.”91 Fried’s distinction allows us to recognise the problem identified by Bennett and see his turn to Stella as re-centring the painting in the experience of the beholder. In contrast to the artists celebrated in Fried’s “Three American Painters,” Bennett is forced to do the work of both exposing this problem and overcoming it.

Bennett achieves exposure through the acknowledgment of the painting’s condition as an object. Bennett adopts Stella’s strategy of using line to acknowledge the literal shape of the canvas. Fried argues that Stella used the rectangular arrangement of lines to echo the shape of the canvas, in a strategy that exceeded in formal consistency the problematic developed by Mondrian.92 Indeed, the first of Stella’s “black paintings,” writes Fried, “amounted to the most extreme statement yet made advocating the importance of the literal character of the pictorial support for the determination of pictorial structure.”93 It is worth dwelling on Fried’s account for a moment, since I am arguing that Bennett is directly responding to the problem of defeating literalism posed by Stella. The aggression in Fried’s tone as he rejects the literalist view is notable:

According to this view, the assertion of the literal character of the picture support manifested with growing explicitness in modernist painting from Manet to Stella represents nothing more nor less than the gradual apprehension of the basic “truth” that paintings are in no essential respect different from other classes of objects in the world…[But] the position I have just adumbrated is repugnant to me…I am arguing that only one’s actual experience of works of art ought to be regarded as bearing directly on the question of which conventions are still viable and which may be discarded as having outlived their capacity to make us accept them, in the face of our awareness of their precariousness, circularity and arbitrariness, as essential and even natural…Stella’s belief in the continued viability of certain pictorial conventions would be no more than touching if it were not objectified in paintings whose density of vital presence testifies that these conventions are not in fact exhausted.94

Fried insists that Stella instils value into the conventions he adopts, which defeats the literal character of the paintings as objects. The parallel I want to draw is that Bennett’s use of near identical conventions for acknowledging the literal character of the painting is also aimed at defeating objecthood, except it is his own as much as the painting’s. Bennett’s exposure of the painting’s objecthood forces the viewer to recognise the paintings as a painting and not as an objectification of the artist’s identity. Moreover, critical accounts that emphasise the artist’s identity will now sound hollow since the literalism underlying their account of the object is exposed. These accounts will look past the painting—treating it as a mere object the experience of which “belongs” to the viewer—to the identity of the artist, which is objectified in the painting. As Darby English notes, such a gaze “illustrates the mechanism by which racial blackness achieves human embodiment, to reify and envelope the black subject in what Fanon calls a ‘crushing objecthood.’”95 Bennett embraced a kind of objecthood as a strategy to expose the “self-mutilation” involved in enforced objecthood.96 He cites the artist Adrian Piper,97 who, in works like Untitled Performance for Max’s Kansas City (1970) “presented [herself] as a silent, secret, passive object seemingly ready to be absorbed into [the audience’s] consciousness as an object.”98 Kobena Mercer writes, “to be an object in this sense is to resist assimilation into the ego-consciousness of the audience to whom the performance was addressed.”99 One mark of this strategy, according to Moten, is that it draws “not…an attention to objects but the aversion of one’s gaze from objects.”100 This strategy, then, exposes the way the literalism of the interpretative framework of identity looks past the painting by treating it in its objecthood.101 Both Bennett and Piper sought to neutralise this function of race in the experience of their art.

The exposure is further achieved for Bennett by the decision to cite some of Stella’s most controversial paintings from the “black series,” like Die Fahne Hoch! (1959), The Marriage of Reason and Squalor, II (1959), and Arbeit Macht Frei (1967).102 Despite their titles, Stella insisted that “what you see is what you see,” a statement taken more as a provocation than a genuine statement by critics.103 Yet, like Stella, Bennett insists “what you see is what you get…The contemplation of the object in itself is nothing more than what one sees before one’s own eyes. There is nothing to hinder the viewer from having the aesthetic experience.”104

Fried guides us away from the scrutiny of motives or “the act of making paintings.” 105 “What matters,” he writes, “is that the paintings themselves manifest a high degree of formal self-awareness” through which modernist painting can “change, transform and renew itself.”106 Fried’s aversion to the “act of making paintings” demonstrates an aversion to psychologisation rather than to intention per se.107 Psychology, like identity, can easily become another trap, as evinced by Tim Riley Walsh’s description of the abstracts emerging from a “contradictory tug of war between [Bennett’s] empathic and emotive self and their opposite—a desire for distance, even indifference.”108 Yet expressive intention applied to painting need not imply interest in the beholder’s own emotional investment; indeed, we could see it as neutralising this interest. As Riley Walsh accurately writes, “to stand in front of a Stripe painting is to find one’s familiar relationship with a Bennett work upturned. The viewer looks upon the repeating bands of black, white or colour from an unknown, ambiguous position.”109 They do so only because of the residual narcissistic racial vision that is de-stabilised by its exposure. Such exposure does not, however, entail “holding up a mirror to us, asking us to consider what we see when we stand before these works” since part of their de-stabilising, exposing effect is produced by their indifference to us.110 A mirror is a metaphor for exposure we should avoid since it turns the focus on the beholder without the possibility of seeing beyond the reflection to the work. The work is opaque and obscured to the extent that we see ourselves; it is present to the extent that we do not.111 Having reached the point at which Bennett was “close to abandoning my project altogether in attempt to avoid banal containment as a professional Aborigine,”112 the Stripe series offered a strategy to avoid the “psychic black hole” in which critics had constrained him.113 Bennett asks us to reconsider the interpretative frameworks used to apprehend him within his work.

Conclusion

Since their appearance, the Stripe abstracts have forced critics to reckon with Bennett’s interrogation of the role of identity in the meaning of painting. I quoted at the beginning Gellatly’s attempt to capture the experience of the paintings by placing apostrophes around Bennett’s name, both heightening and neutralising his identity in the interpretation. Gellatly notes that these “beautiful and meditative paintings provide a space for contemplation for artists and audience.”114 I agree. But it is an abiding irritation in art history that contemplation can become the narcissistic echo of the bourgeois (or colonial) viewing subject reflecting on nothing but itself.115 This reflects the vitiated ideal of a genuinely neutral beholder, an ideal formulated by Fried, Adorno, and other theorists of modernism since Kant. This ideal affirms the possibility of our perceiving paintings not as the objectification or affirmation of identity but as bearing conviction in the possibility of artistic achievement that might be, as Bennett writes, “common to all humanity.”116

By engaging directly with Stella’s black paintings, Bennett’s Stripe series renews our conviction in a set of conventions associated with modernist painting. The price of this renewal is the abandonment of the project of disencryption that occludes the painting by overlaying it with the interpretative frame of identity. To achieve this, Bennett explicitly adopted the set of problems posed by Stella and transformed them into a way of exposing the effect of racial vision and averting its imposition. The paintings present a forbidding austerity to the critic armed with the metaphysics of identity, but they are phenomenologically dense and historically engaged to anyone willing to engage in their aesthetic claim on our experience.

-

Paul Carter, Meeting Place: The Human Encounter and the Challenge of Coexistence (MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013). ↩

-

Ian McLean, “Gordon Bennett’s abstract art: The aesthetics of commitment and indifference,” in Gordon Bennett: New Work (Adelaide: Greenaway Art Gallery, 2004), n.p. ↩

-

Maggie Nelson, On Freedom: Four Songs of Care and Constraint (London: Jonathan Cape, 2021), 66. ↩

-

The term “fugitive,” similar to Carter’s term “vagrancy” in the epigraph, is developed on the basis of a different historical context throughout the work of Fred Moten, for example in “The Case of Blackness,” Criticism 50, no. 2 (2008): 177–218, where a “fugitive movement in and out of the frame, bar, or whatever externally imposed social logic…inheres in every closed circle, to break every enclosure” (179). More well-known is the use of the term in Moten and Stefano Harney, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (Wivenhoe and New York: Minor Compositions, 2013). The phrase that resonates strongly here is Moten and Harney’s “fugitive enlightenment…the life stolen by enlightenment and stolen back” (28). ↩

-

Gordon Bennett, “The Manifest Toe,” in Be Polite™ (Brisbane and Berlin: Institute of Modern Art and Sternberg Press, 2016), 85. Bennett explains that he “foregrounded perspective” in earlier works Triptych (1989), Freedom Fighters (1989) two Interior works from 1991, (Abstract mirror) and (Abstract eye) in order to “expose” the “ideological framing of the observing subject and the observed ‘object’ within a Eurocentric power structure. By disrupting this field of representation, I hoped to implicate the observing subject in the production of meaning, not in order to affirm the subject but in order to stimulate thought, and the possibility of exceeding the historical parameters that frame it.” (85, my emphasis.) ↩

-

Michael Fried, “Three American Painters,” in Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1998), 239. This frame operates in contrast with that of Tim Riley Walsh, who locates the abstracts in a conceptual tradition, attending in particular to Bennett’s interest in the work of Robert MacPherson. See “A Transient Separation: Gordon Bennett’s Abstract Art,” in Unfinished Business: The Art of Gordon Bennett, ed., Zara Stanhope (Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery / Gallery of Modern Art, 2020), 139–157. ↩

-

See for instance, Walter Benn Michaels, The Beauty of a Social Problem: Photography, Autonomy, Economy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 43–70 and Mathew Abbott, “Modernism and the Discovery of Finitude,” in Michael Fried and Philosophy: Modernism, Intention, and Theatricality, ed. Mathew Abbott (London: Routledge, 2018), 18–32. ↩

-

Fried’s pugnaciousness, even aggression (on which I comment below), has been taken to task by Amelia Jones in “Art History/Art Criticism: Performing Meaning,” (in Performing the Body / Performing the Text, ed., Amelia Jones and Andrew Stephenson [London and New York: Routledge, 1999], 36–51) which proposes that Fried’s famous “Art and Objecthood” exploits but represses the very theatricality it attacks, exposing the desire of the interpreter more than any quality of the art (amongst other charges). J. M. Bernstein mounts a more philosophical (as opposed to stylistic) criticism of Fried in “The Aporia of the Sensible—Art, Objecthood, and Anthropomorphism: Michael Fried, Frank Stella, and Minimalism” (in Against Voluptuous Bodies: Late Modernism and the Meaning of Painting [Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006], 117–143), arguing that Fried proved unable to properly see that the “best literalist works are not, in fact, literal, mere things. They are the artistic presentation of objecthood, anthropomorphism at the limit of its power to inform…[And moreover, what] Fried seems not to notice, what he must remain insensitive to, is how the exhaustion of visible meaning affects Stella’s works, how its dryness or ready availability to critical comprehension tokens the exhaustion of sensible meaning as emphatically as does the tedium of minimalist works.” (140–141.) My argument in this paper avoids these criticisms since, however astute Bernstein’s remarks, Bennett’s achievement is to turn the “ready availability to critical comprehension” against itself in renewing (rather than simply remembering, melancholically) visible meaning. ↩

-

According to Fried in “Three American Painters,” the challenge of modernist painting is to renew the experience of conviction by reference to “nothing short of firsthand, immediate, physical features of the picture support itself.” (242.) Fried takes up this assertion more programmatically in the notorious “Art and Objecthood,” differentiating the instantaneousness of modernist painting from the duration of minimalist works that cannot be experienced fully at any one time and seem to foreclose the possibility of shared experience. Recently, Anthony E. Grudin has connected Fried’s critical terminology to the effects of capitalism in “Beholder, Beheld, Beholden: Theatricality and Capitalism in Fried,” Oxford Art Journal 39, no. 1 (2016): 35–47. ↩

-

Bennett, “The Manifest Toe,” 52. ↩

-

SEQEB refers to the South East Queensland Electricity Generating Board. ↩

-

Bennett, 71. See 63–64 for the dates of Bennett’s employment. I cannot comment on the direct connection between Bennett’s decision to enter art school and the SEQEB strike, however the coincidence is remarkable. The strike marks a “turning-point” for the union movement in the face of anti-union crusades characteristic of neoliberalism, in this case enacted by the notorious Queensland premier Joh Bjelke-Peterson (who is quoted in an epigraph for “The Manifest Toe”). See Simon Blackwood, “Doomsday for the Queensland Labour Movement? The SEQEB Dispute and Union Strategy,” Politics 24, no. 1 (May 1989): 68–76 and for broader context see Elizabeth Humphrys, How Labour Built Neoliberalism: Australia’s Accord, The Labour Movement and the Neoliberal Project (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2019), 93–101. ↩

-

Bennett, 53. ↩

-

Fried, “Three American Painters,” 242. ↩

-

See Helen Hughes, “Skin Deep: The Anatomy of Images in the Art of Gordon Bennett,” in Gordon Bennett, Be Polite™ (Brisbane and Berlin: Institute of Modern Art and Sternberg Press, 2016), who notes how Bennett depicts “images of his own paintings in circulation” (48). ↩

-

Theodor W. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, trans., Robert Hullot–Kentor, ed., Gretel Adorno and Rolf Tiedemann (London: Bloomsbury, 2012), 31. Aligning with the Clement Greenberg–inspired theory of modernist art taken up by Fried (in which artists purify their medium by gradually discovering its essence [See “Three American Painters,” 216: Fried’s discussion of opticality is instructive here, see 224–231]), Adorno writes, “art does justice to the contingent by probing in the darkness of the trajectory of its own necessity.” (157.) ↩

-

Adorno, 5, my emphasis. ↩

-

See Adorno: “Art is related to its other as is a magnet to a field of iron filings” (Aesthetic Theory, 8). We could imagine that the magnetic filings need not point inward but outward. ↩

-

Adorno, 8. ↩

-

The project in the Stripe paintings evokes the dilemma of bourgeois contemplation, particularly the ambivalence towards contemplation in post-Kantian aesthetics, as well as in critical theory and historical materialist aesthetics. Adorno embodies such ambivalence, for instance writing, “Although art revolts against its neutralisation as an object of contemplation, insisting on the most extreme incoherence and dissonance, these elements are those of unity; without this unity they would not even be dissonant.” (Aesthetic Theory, 214; see also 341, and for commentary on Adorno’s concept of aesthetic experience see Espen Hammer, Adorno’s Modernism: Art, Experience, and Catastrophe [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015].) ↩

-

Gordon Bennett and Bill Wright, “Conversation: Bill Wright talks to Gordon Bennett,” in Gordon Bennett, ed., Kelly Gellatly (Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2007), 100. The term evokes Maurice Merleau–Ponty’s connection between the act of painting and visibility through the artist’s body: “It is by lending his body to the world that the artist changes the world into paintings.” See Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “Eye and Mind,” in The Merleau-Ponty Aesthetics Reader: Philosophy and Painting, ed. Galen A. Johnson and Michael B. Smith (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1993), 123. ↩

-

Kelly Gellatly suggests that Bennett’s use of this strategy was to “discourage narrative connection and association.” (“Citizen in the Making: The Art of Gordon Bennett,” in Gordon Bennett, ed., Kelly Gellatly [Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2007], 24.) The use of a strictly sequential numbered series itself is confounded by Bennett, since multiple abstracts are called Number Nine, at least nine according to the Bennett Estate including from 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, and 2008. No aesthetically or politically significant information can be gleaned from the titles; we are left to our own devices. As Riley Walsh puts it, “Bennett’s titles give nothing away. The numbers work to reduce the singularity of these canvases—they become products of a larger and consistent process.” (“A Transient Separation,” 145.) We do not, however, have to see the numbers as denuding the canvases of singularity, or part of a larger process (in the sense Buchloh identifies, which I discuss below in note 38); we might rather see the numbers as intensifying the singularity of the canvasses by bracketing the name as a feature of our experience; impersonal process becomes intentional practice or strategy. ↩

-

Fried, “Three American Painters,” 258. ↩

-

Fried, 258. ↩

-

This allusion to Pollock is discussed by Rex Butler in his introduction to Radical Revisionism (“Introduction” in Radical Revisionism: An Anthology of Writings on Australian Art, ed., Rex Butler [Brisbane: Institute of Modern Art, 2005], 19) and by Nicholas Thomas in Possessions, writing that Bennett “takes Pollock’s technique out of the register in which it has been conventionally understood—as the expression of a creative individual’s tortured psyche—and renders it a vehicle for expressing the repressed in the Australian national psyche.” (205.) Two other works that engage Pollock include Explorer (1991) and Panorama: Cascade (with Floating Point of Identification) (1993) the latter being particularly interesting for my argument. Fried argues that in his numbered paintings, starting with Number 1, 1948, Pollock sought to incorporate line into the painting’s ‘entirely homogeneous, allover in nature’ in such a way as to resist figuration, that is “freed at last from the job of describing contours and bounding shapes…Pollock’s line bounds and delimits nothing—except, in a sense, eyesight.” (“Three American Painters,” 224.) Bennett’s Panorama responds to this challenge by carving non–figurative spaces in black out of an “allover” painting. Bennett, in his “The Manifest Toe,” cites Pollock in reference to the “wounding of the human spirit; overpainted Modernist trace of a Pollock skein as metaphor for the scar as trace, and memory, of the colonial lash.” (106, see also 97–99.) See also Abigail Bernal, “The Colour Black and Other Histories: Gordon Bennett and Jackson Pollock,” in Unfinished Business: The Art of Gordon Bennett, ed., Zara Stanhope (Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery / Gallery of Modern Art, 2020), 67–83. ↩

-

Gellatly, “Citizen in the Making,” 24. ↩

-

Zara Stanhope, “Unfinished Business: The Art of Gordon Bennett,” in Unfinished Business: The Art of Gordon Bennett, ed., Zara Stanhope (Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery / Gallery of Modern Art, 2020), 27. ↩

-

Stanhope writes, following a discussion of the Notes to Basquiat series: “The sense of overwhelming detail in these works disappeared in subsequent paintings, as the background patterning came to the fore, clearly suggesting types of camouflage” (29). ↩

-

Bennett, “The Manifest Toe,” 53. ↩

-

Gellatly, “Citizen in the Making,” 24. ↩

-

Gellatly, 24. ↩

-

Bennett and Wright, “Conversation,” 97. ↩

-

Butler writes “while it can be seen that Pollock (or the critical context around him, which is Bennett’s real target) acknowledges Navajo sandpainting, that Mondrian was fascinated with Jazz, that Preston was influenced by Aboriginal culture and that McCahon was wracked by religious and artistic doubt, all this is only because of Bennett. There is thus a kind of circularity produced here between the past and the present, between Bennett and the subject of his critique, in which Bennett could no sooner offer a re–reading of works than this re–reading is already seen in them in which he could no sooner offer an alternative to tradition than tradition is already seen to be this alternative—but all this…only because of the ‘missing link’ of Bennett himself.” (“Introduction,” 19.) ↩

-

Bennett and Wright, “Conversation,” 97. While Bennett received numerous prizes early in his career, between 1998 and 2014, his work was not awarded, see Stanhope, Unfinished Business, 188. Not significant in its own right, we may nevertheless take this as a rough indication of the commercial and critical popularity Bennett forfeited. ↩

-

Fried, “Three American Painters,” 214. ↩

-

Bennett and Wright, “Conversation,” 100. Butler notes a “lack of interest” among a “younger generation of abstractionists and contemporary Indigenous art[ists]” in “being “Australian.”” (“Introduction,” 30.) But this point serves a post–national curatorial agenda, rather than a post–identity political one. ↩

-

Bennett and Wright, 100. See Ian McLean, “Gordon Bennett: The joker in the pack” in Radical Revisionism: An Anthology of Writings on Australian Art, ed., Rex Butler (Brisbane: Institute of Modern Art, 2005), who describes Bennett’s Home Décor series as “not straight appropriations, but…complex cross–references” (273), citing Margaret Preston, Clifford de Stijl, Piet Mondrian and others. ↩

-

Fried, “Three American Painters,” 218. ↩

-

Against Fried, Benjamin Buchloh asserts that Stella’s abstraction was not the “culmination” of the medium’s “self–reflexivity” but should be understood by “the order of the diagram as a readymade formal organisation…” (“Painting as Diagram: Five Notes on Frank Stella’s Early Paintings, 1958–1959,” October, 143 [2013]: 128.) This intensifies the stakes of Bennett’s citation, since Bennett would not be citing the specific work of another painter but rather something that pre–dated that painter in the environment. Buchloh argues that the advantage of this view is that it allows us “to see more common historical determinations” (129), however, it would do so at the cost of the specific dynamic of freedom and constraint in Fried’s framework. Buchloh reads Stella as transforming “what had been once the emancipatory promises of the modernist grid and of monochrome painting into carceral diagrammatic structures. The repressed dark underside of the modernist grid and of monochromy returns…” (139.) Bennett’s oeuvre arguably anticipates and responds to this critique. On the grid, see also Stanhope, “Unfinished Business,” 19. ↩

-

Butler, “Introduction,” 18. Butler’s comment exemplifies what Bennett himself highlighted in a Foucauldian vein when he writes, “The ways in which black people, and black experiences were positioned and constructed as subjects in the dominant regimes of representation were effects of a critical exercise of cultural power and normalisation.” (“The Manifest Toe,” 84.) ↩

-

See Bennett, “The Manifest Toe,” 81–83. And see also Hughes, “Skin Deep,” 31. ↩

-

See for instance, Ian McLean, “Post-Western Poetics: Postmodern Appropriation Art in Australia,” Art History 37, no. 4 (2014), 628–647; and Ian McLean, “Names,” in Double Desire: Transculturation and Indigenous Contemporary Art, ed., Ian McLean (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014), 24. ↩

-

Butler, “Introduction,” 19. See also McLean, The Art of Gordon Bennett (Roseville: Craftsman House in association with G+B Arts International), 1996: “Bennett not only parodies [Immants Tillers’.” appropriation of Aboriginal art as a type of colonisation (which all appropriation is), but paradoxically reinvents Aboriginality as an ideology in which the will to re–appropriate empowers. On one level Bennett seems to be doing a Tillers to Tillers, a simulacrum of a simulacrum…” (94.) ↩

-

Terry Smith “rejects” the idea that “Bennett, like all those who use appropriative strategies, is trapped within an infinite regress of quotation.” (“Australia’s Anxiety,” in History and Memory in the Art of Gordon Bennett [Birmingham and Oslo: Ikon Gallery and Henie Onstaf Kunstsenter, 2000], 16.) ↩

-

Homi Bhabha illustrates this point well in The Location of Culture (New York and London: Routledge, 2004). He writes that mimicry “menace[s] the narcissistic demand of colonial authority. It is a desire that reverses “in part” the colonial appropriation by now producing a partial vision of the coloniser’s presence; a gaze of otherness, that shares the acuity of the genealogical gaze which, as Foucault describes it, liberates marginal elements and shatters /the unity of man’s being through which he extends his sovereignty.” (126–127.) Bhabha continues, on the theme of fugitivity and secession, writing that mimicry “is like a camouflage, not a harmonization of repression of difference, but a form of resemblance, that differs from or defends presence by displaying it in part, metonymically.” (128.) This point is also forcefully made in Sianne Ngai’s Ugly Feelings ([Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005], 126–173), in which the mimetic inhabitation of another’s identity in an act of adoration destroys the “original,” makes it unviable as a subject position. Ngai also draws on Fanon in commenting on representations of race in literary modernism, describing a “racialised protagonist with whom we can neither fully identify nor fully disidentify.” (190.) ↩

-

Aileen Moreton-Robinson, “The White Man’s Burden: Patriarchal White Epistemic Violence and Aboriginal Women’s Knowledges within the Academy,” Australian Feminist Studies 26, no. 70 (2011): 417. ↩

-

See Rex Butler, “What Was Abstract Expressionism? Abstract Expressionism after Aboriginal Art,” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, 14, no. 1 (2014): 76–91, which risks making “Aboriginal art today” a site that for “white critics” “takes us back, as abstract expressionism intended to do, to the first “primitive” engagement with the work of art: outside of categories, outside of histories, outside of protective or distancing ironies or sublimating aesthetic comparisons.” (89.) Butler wants to turn Aboriginal art into something like what Lascaux was for Bataille; a fantasy of what “the taste of art, the one we think of ourselves touched by at Lascaux, on its first date” might have been. (Jean-Luc Nancy, “On Painting (and) Presence,” trans., Emily McVarish, in The Birth of Presence, trans., Brian Holmes & others [Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1993], 359, and see also Georges Bataille, Lascaux or The Birth of Art, trans., Austryn Wainhouse [Skira: Geneva, 1980].) The fantasy operates on the elision of the history of colonialism, or history as such. In order to achieve this outside, Butler posits the distancing device of the “vulgar” or “primitive” (Butler, “What Was Abstract Expressionism?,” 87) that the “encounter with Aboriginal art is bringing back to us” since the decline of serious abstract expressionism, its “sincerity” (89) and exception to the tradition. Bennett’s strategy proposes that this is inadequate, that the outside is constituted by what (and how) it negates not by the mere absence or lack of knowledge of the tradition, and that genuinely critical modernism is not outside history but immersed in contesting it. ↩

-

McLean, “Gordon Bennett,” in Radical Revisionism, 273. ↩

-

Juan Davila quoted in Toni Ross, “Questions of ethics, aesthetics and historicism in Gordon Bennett’s painting: A reply to Ian McLean,” in Radical Revisionism: An Anthology of Writings on Australian Art, ed., Rex Butler (Brisbane: Institute of Modern Art, 2005), 288. ↩

-

Wagner quoted in Darby English, How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007), 20. ↩

-

Ross, “Questions of ethics, aesthetics and historicism” in Radical Revisionism, 286–287. ↩

-

Stanhope, “Unfinished Business,” 21. ↩

-

Bennett quoted in Bernal, “The Colour Black and Other Histories,” 73. ↩

-

I thank an anonymous reviewer for pushing me to make this point. See also Bennett and Wright, “Conversation,” 100 for a discussion of Emily Kame Kngwarreye as a source for the Stripe series alongside Stella (which I discuss further below). ↩

-

Ross, “Questions of ethics, aesthetics and historicism,” 285. Early works such as Self–Portrait (Schism) (1992) and Self portrait (Ancestor figures) (1992) are interpretable through psycho–dramatic lens, but also parodies or literalisations of family history. We can read them neither as straight constructions nor straight de–constructions. They should force us to ask what we want from the psycho–drama of the artist’s identity. See McLean, The Art of Gordon Bennett on psycho–dramas and the discussion of Requiem for a Self Portrait (1988) which “Bennett jokingly refers to…as his first abstract painting. His first conscious attempt to portray himself produced an image of obliteration and death, a requiem.” (82.) ↩

-

Ross, 285. McLean presents Bennett as “picturing” a subjectivity, writing that since his early “postmodernist aesthetic, in more recent years he has more consciously pictured a metaphysics of identity for the postcolonial subject.” (The Art of Gordon Bennett, 103.) ↩

-

Davila in Ross, 289. Compare Adorno, Aesthetic Theory: “The ideal of blackness with regard to content is one of the deepest impulses of abstraction…Along with the impoverishment of means entailed by the ideal of blackness—if not every sort of aesthetic Sachlichkeit [objectivity]—what is written, painted, and composed is also impoverished; the most advanced arts push this impoverishment to the brink of silence.” (53–54.) See also Buchloh on the “withdrawal of colour from postwar painting” in “Painting as Diagram,” 134. ↩

-

It seemed that regardless of Bennett’s efforts, when “Bennett disavowed his aboriginality…this only confirmed his sophistication in the eyes of the art world.” (McLean, “Post–Western Poetics,” 634). Elsewhere, McLean has noted that Bennett’s later work “takes issue with the mechanism of doubling,” which gently folds the re–representation of the offending material back into the tradition. See “The Aura of Origin: Ghouls and Golems in Gordon Bennett’s Art,” Artlink, 21, no. 4 (2001): 27. Buchloh’s assessment of Stella as performing an “exact duplication of newly emerging pictorial strategies” (“Painting as Diagram,” 133) can be seen in this light as well. ↩

-

That is, despite the protestation that “the subject of desire is not so much represented in the picture, but emerges at points where the symbolic structure stumbles, where we encounter the other’s desire as enigma.” (Ross, “Questions,” 289.) ↩

-

Butler, “Introduction,” 19. Bennett continues to be cast in this role amongst other artists of his generation such as Richard Bell, Judy Watson and Tracey Moffat. See for instance Ann Stephen, “Beyond trauma narratives” in Through a lens of visitation (Melbourne: Monash Museum of Art, 2021), 51. Stephen contrasts these artists with D Harding whose “process of immersion in linguistics began to distance him from the prevailing “identity politics” of contemporary Indigenous art that exposes oppression and trauma to shame the (Western) viewer.” (51.) Stephen cites Susan Best’s Reparative Aesthetics (2016) in making the point that Harding achieves this distance by making “private paintings.” In contrast, Bennett’s paintings are precisely public and viewable, fully visible in a way that challenges what we imagine we are seeing when we see race. Wes Hill also usefully distinguishes Bennett and Bell, commenting, “Bennett questioned the ways in which history defines his identity, but…he also questioned the ways in which history defines ‘us’—black, white and in–between, hinting at a collective stake in the question of Aboriginality. In this Bennett contrasts with an artist such as Richard Bell, who…appears less internally conflicted by the idea of an art purpose–built for a political identity. In other words, Bennett was suspicious of his iconoclastic signifiers becoming hitched to an authoritative and professional political voice.” (“Gordon Bennett: Selected Writings,” Artlink, 42, no. 1 [March 2022]: 101.) ↩

-

English, How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness, 3. ↩

-

English, 20. ↩

-

English, 34. ↩

-

English, 34. ↩

-

English, 35. In Entanglements, or Transmedial Thinking about Capture (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012), Rey Chow also notes the “programmatic dismantling of identification” as an artistic strategy, highlighting that the “ghosts of identification refuse to die, and typically return to haunt scenarios…that accompany the pursuit of objects, be these objects human or non–human.” (6.) ↩

-

Bennett, “The Manifest Toe,” 97. ↩

-

English, How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness, 25. ↩

-

English, 3. ↩

-

By way of contrast, Gellatly cites Stanhope’s comments in her essay for the Three Colours show in 2005 on Bennett’s “John Citizen” persona as ‘“withdrawal and concealment”’, commenting that the abstracts provide ‘a release from being “Gordon Bennett” and the weight and expectations surrounding his practice.” (18.) ↩

-

Bennett, “The Manifest Toe,” 90. ↩

-

Bennett, 98–100. Stanhope concludes by restoring Bennett to a progressive narrative in which the conditions in which his work can be “‘accepted’…are yet to arrive.” (“Unfinished Business,” 30.) Similarly, Riley Walsh somewhat tritely proposes that “Living in a world built by oppression means that for artists of Bennett’s conviction, there is always unfinished business to attend to.” (“A Transient Separation,” 145.) There is a distinct echo of Adrian Piper’s statement of withdrawal (May, 1970) which, “rather than submit the work to the deadly and poisoning influence of these conditions, I submit its absence as evidence of the inability of art expression to have a meaningful existence under conditions other than those of peace, equality, truth, trust and freedom.” (Piper quoted in Lucy R. Lippard, Six Years: The dematerialisation of the art object from 1966 to 1972 [Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997], 168.) Suffice to say, under such conditions, for Adorno, there would be no such thing as art; the resolution of all tension and contradiction is the suffocating, therapeutic ideal of liberal progressivism. On Piper and therapeutic liberalism, see Christopher Lasch, The Minimal Self: Psychic Survival in Troubled Times (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1984), 150–151. ↩

-

Bennett and Wright, “Conversation,” 100. ↩

-

While some take for granted that Fried’s art historical framework is dialectic, such as Marnin Young (“The Temporal Fried,” nonsite, 21 [2017], accessed March 20, 2022, https://nonsite.org/the–temporal–fried/), others have expressed reservations about such a characterisation. Implicit, for instance, in Benjamin Buchloh’s critique of Fried is that its dialectic is insufficiently materialist (see “Painting as Diagram,” 128–129), while both Knox Peden (“Grace and Equality, Fried and Rancière (and Kant),” in Michael Fried and Philosophy: Modernism, Intention, and Theatricality, ed., Mathew Abbott [London and New York: Routledge, 2018], 192–193) and Stephen Melville (Seams: Art as a Philosophical Context [Amsterdam: G+B Arts, 1996], 157) articulate Fried’s dialectic in qualified terms. For Melville, Fried’s art historical “story is dialectically charged, but is, in principle at least, not submitted to the authority of any Absolute” (157), while for Peden “there are good reasons to resist a too dialectical conception of Fried’s writing on art” (192). Notable also are Fried’s vehement assertions that his dialectic is not that of a materialist historian, as he remarks in his reply to T.J. Clark (“How Modernism Works: A Response to T.J. Clark,” Critical Inquiry, 9, no. 1 [1982]: 228) and his recently resuscitated review of John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, “Marxism and Criticism” (nonsite, 35 [2021], accessed March 20, 2022, https://nonsite.org/marxism–and–criticism/,) originally published in 1962. ↩

-

Bennett and Wright, “Conversation,” 98. ↩

-

This claim is related to but different from the argument of Michael W. Clune in In Defence of Judgment that “Racial marking provides an index of social structure that also enables people to perceive economic injustice. In America, race makes class visible. [Gwendolyn] Brooks shows us racial seeing as a paradoxically progressive economic resource by imagining a world without it.” ([Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021], 155.) While Clune emphasises the information that is encoded by Brooks’ poem, in which racial vision is made evident, I suggest that Bennett is not trying to make any kind of information available. In other words, while Clune wants to bypass seeing in order to achieve understanding (see 176), Bennett wants to expose the existing modes of understanding as insufficient and inadequate and return us to the act of seeing. ↩

-

Fried, “Three American Painters,” 225. See Anna C. Chave, “Minimalism and the Rhetoric of Power,” Arts Magazine, 64, no. 5 (January 1990): “Stella’s black paintings may be read as a kind of cancelled poetry that impedes or frustrates reading.” (50). Chave’s interpretation insists on being able to “read” what intends to “frustrate reading,” and what she calls minimalism’s “refusal to picture something else” (61), as though these were the alternatives. Similarly, we should be wary of the binary of “identity” and “invisibility” or “privacy,” noting instead the force of “disidentification” (see for instance, Jacques Rancière, “Politics, Identification and Subjectivization,” October, 61 [1992]: 58–64). ↩

-

Fried, 228. ↩

-

Fried, 229. ↩

-

See Fried’s discussion of Mondrian in the lineage to Stella in “Three American Painters,” 254–255. Unsurprisingly, Fried ultimately prefers Stella’s “solution” to Mondrian’s. ↩

-

Nicholas Thomas, Possessions: Indigenous Art/Colonial Culture (London: Thames and Hudson, 1999), 208. ↩

-

See for instance Kobena Mercer on “the tendency to conflate the autobiographical material put forward as the subject matter of her [Adrian Piper’s] artistic investigation with the critical intelligence that is the investigation’s agent.” (“Contrapositional Becomings: Adrian Piper Performs Questions of Identity,” in Adrian Piper: A Reader, ed., Cornelia Butler and David Platzker [New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2018], 106.) ↩

-

Bennett, “The Manifest Toe,” 79 and 116. ↩

-

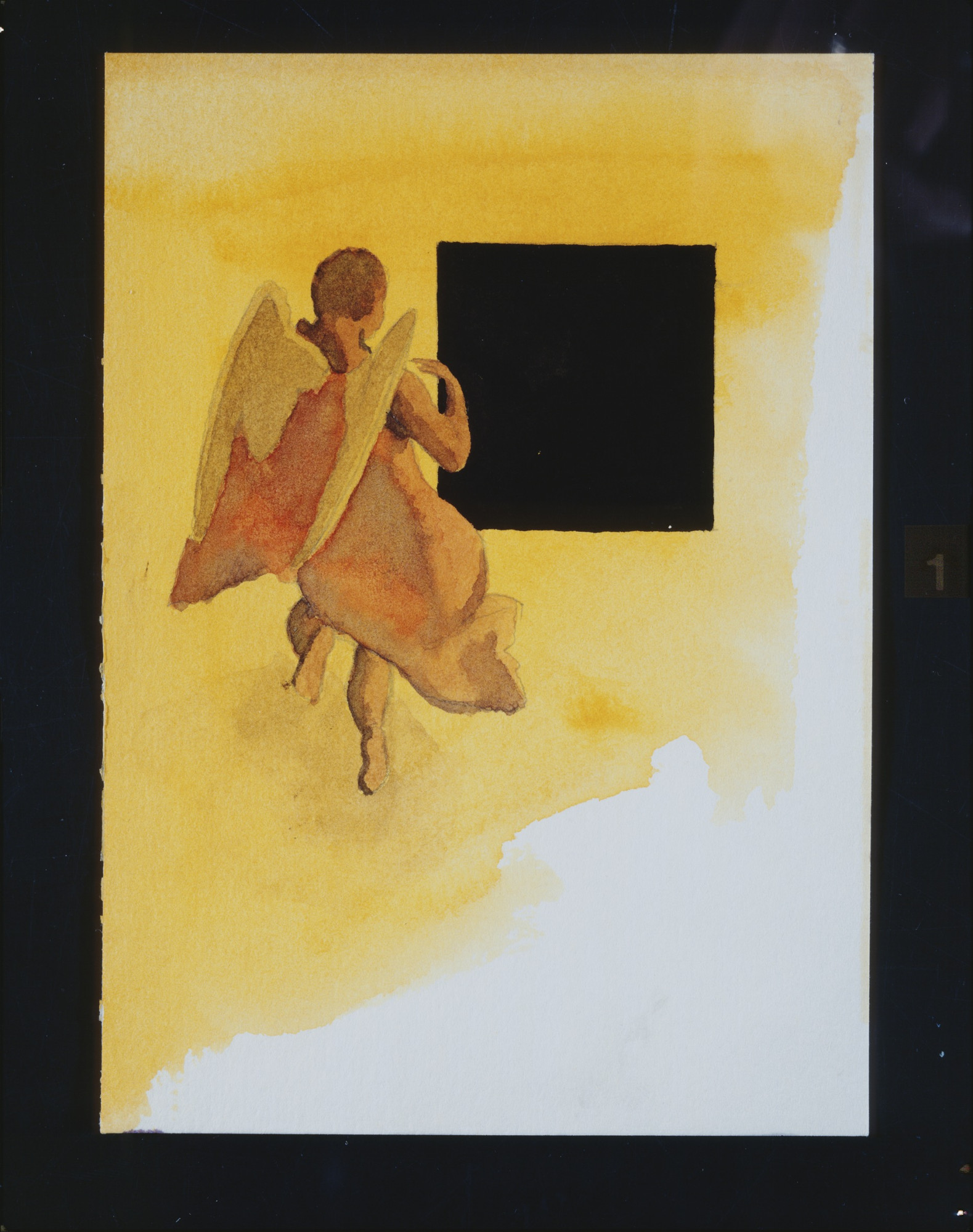

The tension between representing affirming and de–constructing is illustrated in McLean’s comment that in Bennett’s use of the “black square” in Untitled (1989), “Aboriginality has not evaporated, but is repressed in a black Malevich–like square, an absence heavy with the residue of metaphysical presence; black as presence, not absence.” (The Art of Gordon Bennett, 88–89, see also Gellatly, “Citizen in the Making,” 12.) The Malevich motif reappears in Contemplation (1993) to challenge this assessment. However, it is placed seamlessly into the same narrative by McLean as an emblem of “the black absence repressed in Euro–Australian discourses.” (103.) One thing notable about these two Malevich citations is that they are effectively rendered meaningless by the immediate turn to blackness as racial identity. Although McLean uses the discussion to signal the “impossibility of an identity politics,” nevertheless this remains the frame and all discussions of the iconographic significance of the baroque angel, and the implication of transcendence in Malevich is eradicated. Terry Smith persists in this eradication despite noting Malevich’s “transcendental direction” in his obituary for Bennett (“Australia’s Anxiety Again: Remembering the Art of Gordon Bennett,” Eyeline, 82 [2014]). Justin Clemens’ “The Analphabeast” (in Gordon Bennett, ed., Kelly Gellatly [Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2007], 106–110) demonstrates the tendency to immediately name others; the art cannot but disappear between the rush to find the “appropriate” appropriation, and the rush to fix Bennett’s identity position. ↩

-

Thomas, Possessions, 199. ↩

-

Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, 25. ↩

-

Following Jacques Lacan, by “narcissistic” I mean the closed loop of self–reflection driven by anxiety about the other’s image of us (of me). See Jacques Lacan, Écrits, trans., Bruce Fink with Héloïse Fink and Russell Grigg (New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2002), 78–79. ↩

-

See Fried, “Three American Painters”: “All judgments of value begin and end in experience…” (215.) ↩

-

Bennett, “The Manifest Toe,” 86. ↩

-

McLean, “Gordon Bennett: The joker in the pack,” 272. ↩

-

Homi Bhabha also recognises in the colonial gaze a “narcissistic authority” that can become “the paranoia of power” (The Location of Culture, 142). ↩

-

Fried, “Art and Objecthood,” in Art and Objecthood, 153–154. ↩

-

Fried, “Three American Painters”: Fried writes that in Mondrian “the coloured rectangles are bounded on as many sides as lie within the picture by black lines which provide the most important structural element in it, while no such black lines run between the coloured rectangles and the framing edge.” (254.) Fried qualifies that this is “not an argument to the effect that Stella’s paintings are superior to Mondrian’s. It does suggest, however, that they are more consistently solutions to a particular formal problem—roughly, how to make paintings in which both the pictorial support and the individual pictorial elements make explicit acknowledgment of the literal character of the picture support…” (255.) ↩

-

Fried, 251. ↩

-

Fried, 255–256. See also Adorno, “Art that is merely a thing is an oxymoron. Yet the development of this oxymoron is nevertheless the inner direction of contemporary art.” (Aesthetic Theory, 79; see also 120.) ↩

-

English, How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness, 36. ↩

-

Bennett, “The Manifest Toe,” 107. Riley Walsh connects Bennett’s abstracts with Robert MacPherson’s investigation of “pain through an analysis and deconstruction of painterly gestures.” (“A Transient Separation,” 143.) Rather than move with the conceptual tradition away from the painterly gesture, however, it strikes me that the connection with Stella de–emphasised by Riley Walsh actually heightens the painterliness of the Stripe series. See Bennett and Wright, “Conversation,” 100. ↩

-

Bennett, 72. Bennett’s works such as Performance with Object for the Expiation of Guilt (1995) adopt some of Piper’s strategies. I cannot comment in detail here on the connection between Bennett and Piper. ↩

-

Piper in Kobena Mercer, “Contrapositional Becomings,” 113. Ian McLean helpfully directed me to this essay. ↩

-

Mercer, 113. ↩

-

Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 234. ↩

-

Mercer writes: “Our understanding of [Piper’s] work, however, is compromised…by the reductive terminology that pervades discussions of identity and difference in art…[The] critical ingenuity of her performative turn continues to unsettle the complacencies of present–day identity politics, which cling to the proprietorial [sic] notion that a self is a fixed entity that you own.” (“Contrapositional Becomings,” 103.) ↩

-

See https://whitney.org/collection/works/2964, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/80316 and https://whitney.org/collection/works/8109 for these works respectively. ↩

-

Stella quoted in Anna C. Chave, “Minimalism and the Rhetoric of Power,” 50. Chave describes the “black paintings” as “forcing viewers into the role of victim” (49), a reversal (from artist as victim) that one can imagine finding compelling as the first turn in the screw of an interpretation that emphasises identity. However, we should note the centrality of the viewer to Chave’s interpretation, not their experience of a painting. Chave seems repulsed by the paintings’ “refusal to picture” (61). Buchloh discusses the “non–reaction” to Stella’s titles in “Painting as Diagram,” 135–141; he offers a quasi–psychoanalytic reading of “parricidal dialogue” (138). ↩

-

Bennett and Wright, “Conversation,” 99. ↩

-

As Buchloh argues, “Stella’s abstractions—unlike the Black Paintings by Rauschenberg, on the one hand, and Reinhardt, on the other—would be the only ones that could in fact be rightfully called “diagrammatic” since they are actually enforcing a given spatial and linear symmetrical schema that rigorously displaces all claims and pretences to compositional decision–making processes or authorial intentions.” (“Painting as Diagram,” 128, my emphasis.) ↩

-

Fried, “Three American Painters,” 236 and 218. See Bennett and Wright, “Conversation”: “I found people were always confusing me as a person with the content of my work.” (97.) ↩

-

See Walter Benn Michaels, The Beauty of a Social Problem, 43–70 and ‘“When I Raise My Arm”: Michael Fried’s Theory of Action,” in Michael Fried and Philosophy, ed., Mathew Abbott (London and New York: Routledge, 2018), 33–47. For critical commentary on Michaels’ interpretation of Fried and concept of intention, see Mathew Abbott, “Recognising Human Action,” nonsite, 32 (2020), accessed September 20, 2022, https://nonsite.org/recognizing–human–action/. ↩

-

Riley Walsh, “A Transient Separation,” 140. ↩

-

Riley Walsh, 140. ↩

-

Riley Walsh, 142. ↩

-

“Presentness is grace,” wrote Fried (“Art and Objecthood,” 168). Peden comments, responding to Fried’s qualification that “We are literalists most or all of our lives,” (168) that “Grace qua presentness is a kind of exemption, outside time and its order of form of phenomenal manifestation. The problem of grace as presentness is strictly analogous to the Kantian problem of freedom. Secular thought in its myriad forms struggles to find a place for freedom in the natural order, often resting content to treat freedom as a norm or convention at best. The overriding idea is that a free act cannot be caused or externally compelled if it is to merit the designation “free.”” (“Grace and Equality,” 192.) ↩

-

Bennett, “The Manifest Toe,” 119. ↩

-