Editors’ Introduction

Contested borders and expansionist claims to sovereignty dominate the news cycle today. From Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine, following the annexation of Crimea in 2014, to China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea, these extra-territorial foreign policy stances are often posed in opposition to the US and its allies. Yet these developments run counter to nearly a century of secessionist movements and withdrawals seeking autonomy from empires around the world. Usually framed as a question for political studies, the aesthetic effects of these geopolitical reconfigurations are rarely a concern for art history. Instead, the discipline’s focus on secession has most often been on an avant-gardism distanced from the vicissitudes of state entities—in rejecting established institutions to create new schools and movements.1 This issue of Index Journal approaches secession in its broadest sense, re-suturing the impulse to withdraw artistically with its political implications for state formation.

Secession takes place on the grounds of sovereignty and is tied dialectically to its opposite: imperialism.2 When “Quit India” was proclaimed by the Congress Working Committee at Wardha in 1942, it meant that the British Raj would cede its centuries-old colonial dominion. Yet Lord Mountbatten and Cyril Radcliffe’s botched partition plan was done in such haste that it wasn’t yet completed in 1947, when power was eventually transferred to the people who would ratify India as a constitutional republic in 1950. The violence unleashed by this British exit suggests the question of when, not if, the time is right to withdraw. Even today, separatist movements abound (for example, Scottish independence from Great Britain is currently a central plank of the governing Scottish National Party’s policy platform). These secessionists operate with just as much intent as those who have come before them, decolonial or otherwise, yet at least in Australia we remain without a clear idea of what sovereignty might mean in the twenty-first century. At its base, it seems that the idea of withdrawal intrinsic to the act is about reclaiming agency; secession is the power to refuse power.

To answer the question of “when” posed by secession, then, we can begin by considering a statement made in 2018 by the editors of Jacobite, a short-lived, online journal of current affairs that seemed to disappear almost as abruptly as it began. The authors address the astonishing pace at which the ostensibly globally hegemonic political consensus has atomised in recent decades:

What we are seeing, first in India, then in Britain, and recently in America, represents the acceleration of a trend 70 years in the making. Since 1945, when the forces of liberal democracy (and communism) stood triumphant and there were less than 50 sovereign states on the planet, the world has fragmented… Today there are around 200. And short of new states, new forms of negotiated sovereignty are appearing throughout the world. This process shows no signs of slowing down.3

This is the rapidly shifting ground upon which we present an issue dedicated to the aesthetic implications of the fragmenting, global-historical reality in which we now find ourselves. For better or worse, it seems that accepting post-modernity, even post-history (which may just mean the liberal order), is a given. Our world is post-Brexit, post-Trump, post-Johnson (and now post-Truss), perhaps very shortly post-Putin too. Yet the failures of nation-states and empires remain in stark contrast to the dominance of corporate-global systems and infrastructure. We are conscious of how we too are enmeshed within this structure, as we write this introduction on Google Docs and publish Index Journal at a web-only address.

At the same time, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has reinvigorated NATO at a juncture where the liberal order had seemed to have passed its zenith. Most significant in Australia and for this issue, however, was the passing of Queen Elizabeth II (whose seven-decade reign nearly outlasted Louis XIV’s; the Sun King remains the longest serving monarch in modern history). These circumstances are the basis for what economic historian Adam Tooze has recently termed the “polycrisis”—the disparate yet interacting shocks that materially affect our present.4 In all these examples, timing is always a key question.

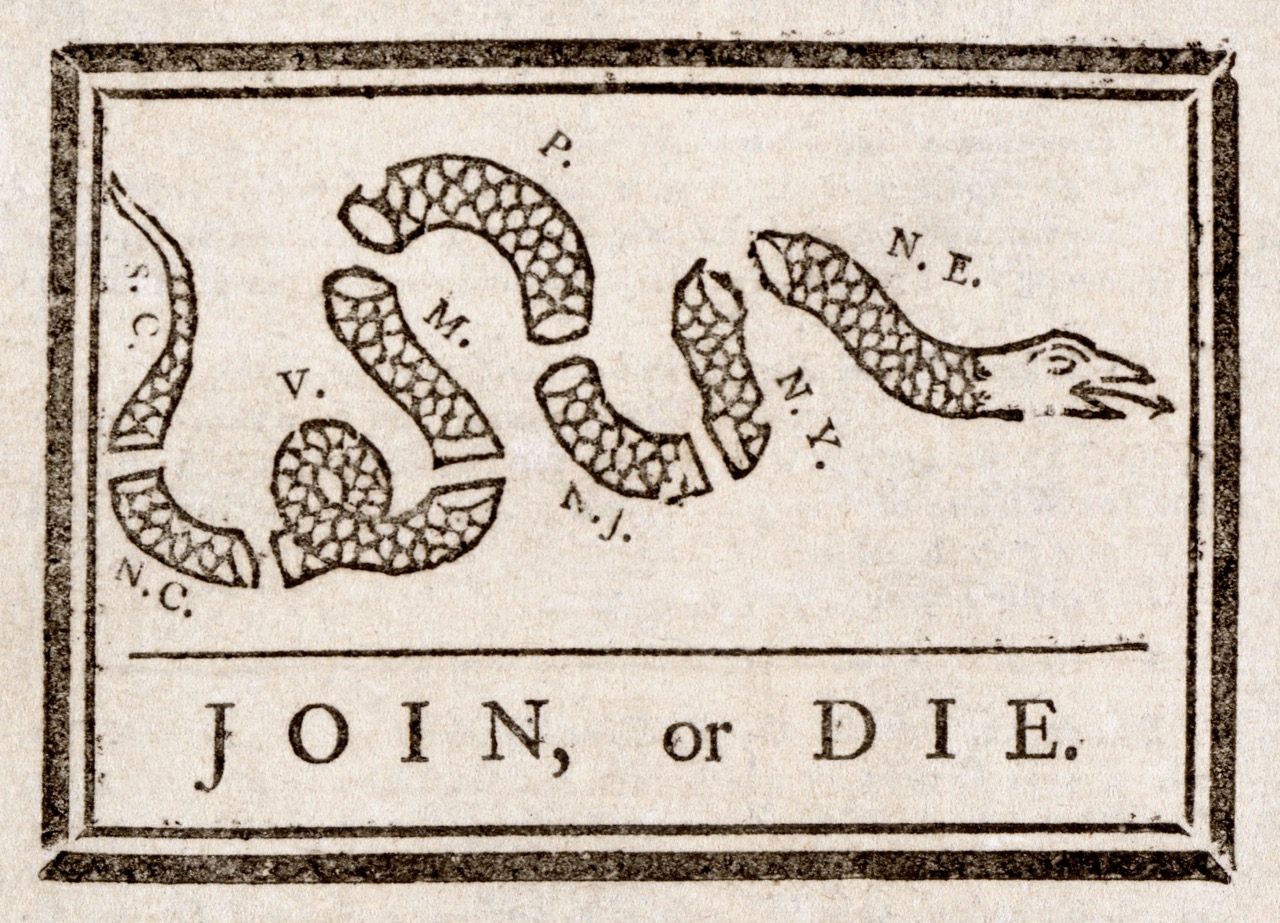

In the US, the consequences for secession—when eleven states withdrew from the Union in 1860 and 1861—can be seen in Benjamin Franklin’s earlier imperative regarding independence: “join, or die.” The term secession is clearer still: “That secession is treason, and that all who uphold it by menace or force, or by giving aid in any degree, or in any manner, are traitors, and legally subject to capital punishment.”5 The January 6 insurrection at the Capitol in 2020 can be seen as the most visible example of the suppressed secessionist movement returning with a vengeance. The symbolism of the insurrection is most potent in its revelation of the cracks in the American experiment; the possibility of a popular refusal to accept the constitutional process is more significant than the actual violence, loss of life, and legal consequences for the rioters who were found guilty of seditious conspiracy (a Civil War era charge).

The nature of these unruly acts of withdrawal contrast sharply with the expansive logic of capital and the permissive practice of empire, which form the conditions for these crises. In our Australian context, secession remains the way we refer to “any withdrawal by an individual or group from an entity of which they had previously been part.”6 It has made itself most apparent in Western Australia (WA), a state which has entertained a more or less constant secessionist movement since federation in 1901. One persistent motivator is the mineral resources it commands within the arbitrarily drawn boundaries that bisect the entire Australian mainland (and yet WA remains 92 percent Crown Land). Throughout the first two years of the pandemic, WA kept borders stubbornly closed to the rest of the world—including the rest of Australia—as a strategy to maintain a near-zero Covid-19 transmission rate. In doing so, the state received the dramatically mediaeval nickname of “the hermit kingdom.”7 At the time of writing, Xi Jinping’s “Middle Kingdom” struggles to maintain a strict set of anti-virus policies, which have become the source of growing civil unrest. As the philosopher Benjamin Bratton has observed, “The global population participated in what future political science may look back upon as the largest control experiment in comparative governance in history, with the virus as the control variable and hundreds of different states and political cultures as the experimental variables.”8 The paradoxical strengths and fragilities of state entities have therefore been brought into view like never before.

In recent years sovereignty has emerged as a prominent idea in popular political discourse. This is most evident in debates about the rights of First Nations people and the illegitimacy of settler-colonialism.9 Responding to this development, the theorist and curator Ariella Azoulay has provocatively argued that the uncritical use of the concept of sovereignty pertains to a persistent regeneration, survival even, of imperialism as a form of political engineering. Azoulay presents this vacillation between the body politic and the bodies of individuals by showing it to be a problem for the organisation and movement of people. Interestingly, she considers it as foremost a concern that emerges from the early modern period:

Regions of the world were partitioned, peoples split and enlisted to wage liberation wars, regional languages were murdered for the sake of standardised languages, and sovereignties declared, producing citizens whose status is the flip side to the status of noncitizens: slaves, refugees, infiltrators, or stateless persons. These devices have been essential to limiting political aspirations, narratives, and histories.10

If Azoulay is right to link the modern use of sovereignty to imperialism, her response to this connection is to expose it as a fabrication, one that she modifies as “differential sovereignty.”11 This idea extends from Benedict Anderson’s “imagined communities,” which are already constrained by their possibility—one where every citizen is compelled to perpetrate the violence of the state.12 Claims to sovereignty and its dialectical twin, secession are a key ideological contest of our time.

As an aesthetic program of modern art, secession also refers to artistic withdrawals from the academy that began in the mid-nineteenth century. Is it possible that these avant-gardes owe more than just a metaphor to their martial counterparts? Throughout these discussions, there is an oscillation detectable between state formations and individuals (artists), which aligns the question of secession along an axis of self-determination. What are the possibilities of sovereignty without territory? And what is the dominion of art?

In the fourth issue of Index Journal, the polyvalence of the word secession extends across six art historical papers of diverse style and subject matter. For some contributors, secession is inseparable from dominant narratives of modern European art history. Others take the term as a starting point for writing non-European art histories; these papers examine the complex receptions of Australian Indigenous art, posit anti-nationalist trajectories of artistic development and ruminate on attempts to create new governance models in Australian community arts organisations.

Ilona Sármány-Parsons’ contribution, “1900—Pyrrhic Victory,” addresses the most prominent art historical Secession: that of fin de siècle Vienna. The article is a new English translation of a chapter from Sármány-Parsons’ recently published book Die Macht der Kunstkritik: Ludwig Hevesi und die Wiener Moderne (The Power of Art Criticism: Ludwig Hevesi and Viennese Modernism). As argued in this paper, Gustav Klimt and his fellow modernists would have foundered without the contemporaneous advent of that other profoundly modern figure, the art critic. The Secessionists’ greatest ally in their ranks was Ludwig Hevesi. Sármány-Parsons thoroughly examines the positions Hevesi and his fellow critics took in alternately stoking and allaying the furore surrounding Klimt’s paintings commissioned for the University of Vienna. Drawing extensively on the press responses to the Secession, it aims at reconstructing the vivid public sphere of debate about new art forms in modern Vienna.

Hevesi famously coined the iconic Secession slogan, emblazoned on the entrance of the group’s gold-domed exhibition building: “Der Zeit ihre Kunst, der Kunst ihre Freiheit” (To the age its art, to art its freedom). If freedom from conservatism and historicism animated these artists, what constitutes artistic freedom in other contexts? Anthony White considers the oeuvre of the artist Anthony Mannix (1953–) and his relationships to various institutions, from museums to artist-run-spaces to psychiatric hospitals in Australia. Mannix has diverse mental health. The impact this has had on his life and art runs through many of his incredible drawings, published in the article. “The Beast is incorrigible,” reads the text captioning one illustration of a scraggly four-legged creature with two protruding eyes (the artist has described “the Beast” as a manifestation of the Unconscious). Mannix’s output is a reminder that for some secession is more easily chosen than others; at times—and this is not unlike the previous examples of independence movements—to withdraw is to stake a claim on survival.

Scott Robinson argues that similar strategies of retreat and obfuscation are at play in Australian Indigenous artist Gordon Bennett’s abstract paintings. Bennett utilised the formal and conceptual vernacular of abstract painting to resist the relentless interpretation of his work through the lens of identity. In doing so, Robinson asserts, Bennett was able to “expose the racialisation involved in the critical reception of [his work] and at the same time avert its imposition on these paintings.” In positioning Bennett’s output relative to the analyses of international modernism, by Michael Fried and others, the conditions for a new framework of “fugitive abstraction” emerge.

The question of what might constitute “unAustralian art” is difficult. Gordon Bennett knew this. The problem has also occupied Rex Butler and A.D.S. Donaldson for the past few decades. In “Australia in the World’s Art Colonies: The World’s Art Colonies in Australia,” the pair proffer a sweeping survey of transcultural artistic exchanges linked to this continent from the late nineteenth century onwards. Butler and Donaldson’s recent research on this subject emerges from a 2020 to 2023 Australian Research Council Discovery Project focussed on the Abbey Art Centre in New Barnet, England, which included a conference on the subject hosted by the University of Melbourne in late November 2022.

The artist colony is most simply summarised as a gathering of artists from different places in one location. In Butler and Donaldson’s words, the art colony might be understood as “a forerunner to contemporary art in its crossing of spatial and temporal borders and flattening of…imposed hierarchies.” The ambitions and foibles of a nascent global contemporary art world are on display in Stefania Portinari’s article on under-researched histories of the Venice Biennale. Portinari assesses the 1968 Biennale’s significance in shaping its later iterations, drawing on sales records, press clippings and searing critiques by then-young radicals Germano Celant and Carla Lonzi.

Finally, in a contribution addressing artistic activities of the very recent past, Amelia Wallin offers a self-reflexive recount of the Disorganising project. Disorganising was undertaken by three artist-run organisations in 2020 and 2021 in Naarm/Melbourne, infamously positioned as the “most locked down city in the world.”13 Liquid Architecture, Bus Projects, and West Space (where Wallin was a curator) temporarily combined funding and resources with the aim of testing new institutional models and working practices. Did the project succeed? How so? How not? In Wallin’s frank assessment, the long-term effects are still unknown. Accounts of attempts at radicality during the extraordinary years of 2020 and 2021 will become increasingly valuable for retroactive analysis as we move further and further from the most frenzied period of the pandemic.

Why do nineteenth century forms of geopolitical statehood, of borders, and sovereignty—of imperialism—appear to be so important for people living two centuries hence? We might ask, thinking of “Quit India,” is secession still a question of when? How does mental health interact with the legitimising apparatus of the art world, and how can the most exclusive and stringent of these structures be challenged? And what are the effects of withdrawing from or remaking the institutions that support artistic production, whether in Vienna in 1897 or Naarm/Melbourne in 2022?

The Editors would like to thank Index Editorial Board members and in particular Paris Lettau, Amelia Winata, Hilary Thurlow, Helen Hughes, and Chelsea Hopper for their erudition and responsiveness. Since its inception, Index has been maintained financially through funding from the School of Culture and Communication at the University of Melbourne, and we thank the School for its support. Thanks must also go to Clare Fuery-Jones, who volunteered her time to copy-edit the issue, and finally, to the writers for their contributions.

-

There are notable exceptions of course. See Richard Wagner’s nineteenth-century writings, collected in Richard Wagner’s Prose Works: Art and Politics, ed. William Ashton Ellis, vol. 4 (New York: Broude Bros, 1966); the collection of Marxist writing on art as Aesthetics and Politics (London: NLB, 1977); T. J. Clark, “God Is Not Cast Down,” in Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999), 225–297; Jo Applin, Lee Lozano: Not Working (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018); Anthony Gardner, Politically Unbecoming: Postsocialist Art Against Democracy (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015). ↩

-

Hannah Arendt, “Part Two: Imperialism,” in The Origins of Totalitarianism (New York: Meridian Books, 1958). ↩

-

The Editors, “This Ain’t Open for Discussion,” Jacobite, February 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20210619184610/https://jacobitemag.com/2018/02/. ↩

-

Adam Tooze, “Welcome to the World of the Polycrisis,” Financial Times, 29 October, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/498398e7-11b1-494b-9cd3-6d669dc3de33. ↩

-

Daniel Gardner, Institutes of International Law, Public and Private, As Settled By The Supreme Court of the United States, And By Our Republic (New York: John S. Voorhies, 1860). See A Lawyer, “The Law of Treason,” The New York Times, 21 April 1961. ↩

-

Gregory Craven, Secession, The Ultimate States Right (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1986), 3. ↩

-

Peter Fitzsimmons, “The personal cost to ‘Mr WA’ of keeping the Hermit Kingdom’s borders shut,” The Sydney Morning Herald, 5 February 2022, https://www.smh.com.au/national/the-personal-cost-to-mr-wa-for-keeping-the-hermit-kingdom-s-borders-shut-20220204-p59tx1.html. ↩

-

Benjamin Bratton, The Revenge of the Real: Politics for a Post-Pandemic World (New York: Verso, 2022), 29. ↩

-

Damien Skinner, “Settler-colonial Art History: A Proposition in Two Parts / Histoire de l’art colonialo-allochtone: proposition en deux volets,” Journal of Canadian Art History / Annales d’histoire de l’art Canadien 35, no. 1 (2014): 138. ↩

-

Ariella Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (New York: Verso, 2019), 45. ↩

-

Azoulay, Potential History, 2019, 45. ↩

-

Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1983). ↩

-

Josh Frydenberg, “Interview with Leon Byner, FIVEaa,” Ministers: Treasury Portfolio, Australian Government, 30 September 2021, https://ministers.treasury.gov.au/ministers/josh-frydenberg-2018/transcripts/interview-leon-byner-fiveaa-17. ↩

Giles Fielke and Cameron Hurst are editors of Index Journal.

Bibliography

- Applin, Jo. Lee Lozano: Not Working. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018.

- Arendt, Hannah. “Part Two: Imperialism.” In The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Meridian Books, 1958.

- Azoulay, Ariella. Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism. New York: Verso, 2019.

- Bloch, Ernst. et al. Aesthetics and Politics. London: NLB, 1977.

- Bratton, Benjamin. The Revenge of the Real: Politics for a Post-Pandemic World. New York: Verso, 2022.

- Clark, T. J. Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999.

- Craven, Gregory. Secession, The Ultimate States right. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1986.

- Ellis, William Ashton, ed. Richard Wagner’s Prose Works: Art and Politics. Vol. 4. New York: Broude Bros, 1966.

- Fitzsimmons, Peter. “The personal cost to ‘Mr WA’ of keeping the Hermit Kingdom’s borders shut.” The Sydney Morning Herald. 5 February 2022. https://www.smh.com.au/national/the-personal-cost-to-mr-wa-for-keeping-the-hermit-kingdom-s-borders-shut-20220204-p59tx1.html.

- Frydenberg, Josh. “Interview with Leon Byner, FIVEaa.” Ministers: Treasury Portfolio. Australian Government. 30 September 2021, https://ministers.treasury.gov.au/ministers/josh-frydenberg-2018/transcripts/interview-leon-byner-fiveaa-17.

- Gardner, Anthony. Politically Unbecoming: Postsocialist Art Against Democracy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015.

- Gardner, Daniel. Institutes of International Law, Public and Private, As Settled By The Supreme Court of the United States, And By Our Republic. New York: John S. Voorhies, 1860.

- Skinner, Damien. “Settler-colonial Art History: A Proposition in Two Parts / Histoire de l’art colonialo-allochtone: proposition en deux volets.” Journal of Canadian Art History / Annales d’histoire de l’art Canadien 35, no. 1 (2014): 130–145; 157–175.

- “The Law of Treason.” The New York Times, 21 April 1961.

- “This Ain’t Open for Discussion.” Editorial. Jacobite, February 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20210619184610/https://jacobitemag.com/2018/02/.

- Tooze, Adam. “Welcome to the World of the Polycrisis.” Financial Times, 29 October 2022. https://www.ft.com/content/498398e7-11b1-494b-9cd3-6d669dc3de33.