Australia in the World’s Art Colonies The World in Australia’s Art Colonies

This essay attempts a survey of the Australian artists who worked in the world’s art colonies from the late nineteenth century until the present. A task until now ignored by art history, it is necessarily only an outline of further work to be done. Our point is that—at least until recently—the time artists spent overseas in art colonies before returning to Australia and the artists who lived in art colonies overseas and did not return have almost entirely been erased from Australian art history. So that this essay is first of all something of an exercise in an expanded art history, including those artists who should rightly be part of a more widely encompassing account of Australian art. But, more than this, we want to suggest that the art colony as such contests the idea of a national art history: that, beyond the specifics of any particular art colony, the principle of the art colony—of artists from different countries or from different regions of the same country living and working together—challenges the assumption that art must come from an identifiable people and place. Put simply, the art colony is always international or even transnational in character. Indeed, in a certain way, the art colony might even be understood as a forerunner to contemporary art in its crossing of spatial and temporal borders and flattening of (if not complete doing away with) imposed hierarchies.

Art colonies have, of course, existed for centuries. Any number of kings and rulers have established courts that brought together artists, writers and musicians from their own and others countries. There was a colony of Danish artists in Rome in the nineteenth century, and the establishment of the Barbizon School just outside of Paris in the mid nineteenth century is one of the markers of the emergence of modernism in painting. But we concentrate here on the Australians in art colonies around the world from the late nineteenth century on because we want to suggest that art colonies open up an alternative to and perhaps even contest those dominant national histories of Australian art that began to be written from around this time.1 In other words, our point is that when those national histories, initially taking the form of exhibitions but also newspaper articles and books, started being written, they overlooked the phenomenon of Australian artists living and working in artist colonies at the same moment. The so-called “genesis” of Australian art is said to take place with the Heidelberg School’s 9 x 5 Impression Exhibition at Buxton’s Rooms in Melbourne in 1889, but it also maintained art colonies around Melbourne and Sydney in the 1880s and 1890s; and our contention is that these art colonies are to place Australian art in an international context, even though they do not always feature artists from overseas, insofar as the artists who started them were aware of them existing in France and England.2

Indeed—and this is to point towards something of a conclusion to this essay—what we ultimately want to suggest is that not only are there Australian artists in art colonies around the world and art colonies in Australia, but that Australia itself might be considered something of an art colony: a place that from a certain perspective has only recently been settled and to which artists from around the world have come to live and work. And this idea of Australian art as an art of the colony and not of the nation, of artists coming together from different places and cultures to work, has been taken up by a series of Indigenous artists and curators to counter a national art history that would largely exclude or marginalise them. As we argue towards the end of this essay, one of the implications of the National Gallery of Victoria’s 2018 exhibition Colony: Australia 1770–1861/Frontier Wars was that of an Indigenous art of both colony and colonisation that sits above and judges a European art that sought to create an art of nation. We also wish to suggest that the model of the art colony has some resonance with the curatorial method of Brook Andrew’s 2020 NIRIN Biennale of Sydney, in which, unlike previous Biennales, works were not simply brought in from overseas, but instead artists met and gathered together to produce work specifically for the occasion. A similar method was also to be seen in the recent documenta 15 in Kassel, whose “director” was an Indonesian art collective, each of whose members invited other artist collectives from around the world to be part of the exhibition. Finally, we suggest, in something of a speculation, the recent movement of contemporary Aboriginal art—the art of Hermannsburg, Papunya and Yuendumu—might also be thought in terms of the art colony. We have artists there from different places and language groups coming together to produce an art that reflects a trans-locality or transnationality, if not in the European sense then in the Luritja sense of tjungurri or “to meet, to join up with, to meet together and become one.”3 And although these places or artists are frequently associated with an avowed or implicit “anti-” or “decolonial” politics, we would want to say that the art colony is not simply to be conflated with the project or ideology of European colonialism. Rather, it is a notion with a specific modern history that we would argue is more aligned with such contemporary concepts as “collective,” “community,” or even “artist residency.” In this sense, we would say that to think those places where Aboriginal art is produced as art colonies is to argue for a certain autonomy or self-empowerment, a distance from or at least lessening of the effects of colonisation.

Needless to say, any treatment of Australian artists in art colonies and art colonies in Australia sits within a much wider discussion of art colonies in general, whose scholarship we can only gesture towards here. There are, of course, studies of the particular art colonies that arise around the world from the late nineteenth century on. We might just mention three: Doris Hansmann’s The Worpswede Artists’ Colony, Katherine Bourguignon’s Impressionist Giverny: A Colony of Artists, 1885–1915 and Robert W Edwards’ Jennie V Cannon: The Untold Story of the Carmel and Berkeley Art Colonies.4 There is even a series of studies—and this is closer to what we are seeking to do in this essay—not of particular art colonies but of the various art colonies of a particular nation. Again, we might just mention three: Adolf Fischer’s ‘Die “Secession” in Japan’, Steve Shipp’s American Art Colonies, 1850–1930 and Elisabeth Fabritius’ Danish Artists’ Colonies: The Skagen Painters, the Funen Painters, the Bornholm Painters, the Odsherred Painters.5 But undoubtedly the study that comes closest to what we are doing is Nina Lübbren’s Rural Artists’ Colonies in Europe 1870–1910, which goes beyond the art colonies of any particular country to examine the art colonies across an entire continent. In the same way as we attempt here, Lübbren looks at artists from one country living and working across the art colonies of another country or the art colonies of different countries. Among her examples are the American painter Theodore Butler, who worked in Barbizon and Concarneau in France and St Ives in England, the Canadian painter William Blair, who worked in Grez-sur-Loing and Giverny in France, and the American painter Philip Leslie Hale, who worked in Rijsoord in Holland and Giverny in France.6 And like us, Lübbren is aware of how this contests any simple national art history, and the way that these artists have been lost to the art histories of their respective countries because they did much of their work elsewhere:

Most of the artists involved are now almost completely unknown outside a small group of specialists or local enthusiasts, and artists’ colonies in general tend to be misunderstood as amusing but marginal footnotes to the central story of modern art.7

Of course, in all of this there is raised the question of what exactly an art colony is, what the necessary conditions are for something to count as an art colony. It is, needless to say, something that all of those authors above grapple with and seek to offer an answer to. For example, Lübbren in Rural Artists’ Colonies suggests that what is necessary for a colony is a proper coming-together of its artists. As she writes: “This book argues that the existence of a close-knit artistic community was an essential precondition for and integral part of artists’ colonies, and formations that follow a different pattern have been excluded.”8 While Brian Dudley Barrett in Artists on the Edge: The Rise of Coastal Artists’ Colonies, 1880–1920 puts forward a slightly broader definition of what counts as an art colony, suggesting that not quite the same level of official organisation, public recognition or even consciousness amongst its residents is necessary: “In practice, many participants were neither dreamers nor friends prior to their move, nor did they share political opinions. They appear to share hopes rather than dreams and were, mostly, simple supportive collaborations of independent yet like-minded modernists rather than deeper fellowships or brotherhoods.”9 And we for our part seek to open the aperture even further. Although in the end we believe that what we describe are art colonies or groups that function like colonies, they do not always see themselves as an art colony and were not always during their own time recognised as such. But nevertheless, we would want to insist, and briefly demonstrate, artists did come to see them as places to live and work and often did seek to make their existence known to the world via classes, lectures, exhibitions, printing presses and other forms of communication. Unlike many of those art colonies above, a number of the art colonies we speak here of are not widely, indeed often barely, written about. We are not only amongst the first to speak of them as art colonies, but frequently the first to recognise them as including Australian artists and as part of Australian art. We cite the existing scholarship where it exists, but also point out that detailed studies of the kind we mention above have not yet been undertaken of many of the art colonies we discuss.

We speak of only two art colonies at any length here, one in each part of our essay: the first is the Abbey outside London in the 1940s and 1950s as a way of speaking of Australians in the world’s art colonies, and the second is Merioola in Sydney at around the same time as a way of speaking of the world in Australia’s art colonies. And this is to say, other than with those two examples, we do not take up how those colonies understood themselves, whether as a defined school, a self-directed group of artists or an open organisation with no predetermined direction. Equally, we do not always trace the effect that time spent in an art colony had upon those artists and sometimes critics who stayed in them, whether it be a lifelong connection with other artists they met and a profound transformation of their work, few lasting connections with little obvious effect on their work or an adversarial relation to the international encounter and a return to the national. Again, some of this is to be seen in the two case studies we present and what would be elaborated in greater detail with each study if we had time and space. But for the purposes of this essay, we want to draw attention to the art colony as a principle with the potential to reshape Australian art: not just to broaden the definition of what counts as Australian art but even to denationalise Australian art altogether. For it might ultimately be to think—this is a crucial and as yet unresolved issue—under what category to put white and Indigenous art together in this country. The answer might be that both are the art of art colonies (as well as the art of colony). And this, to conclude, might be the principle of secession at stake in the art colony: not only that of a particular art colony in relation to the country that houses it, but the principle of the art colony altogether in relation to those national histories of art that were beginning to be written from the end of the nineteenth century.

Australia in the World’s Art Colonies

Let us start here with the Abbey art colony at New Barnet on the outskirts of London overseen by the British art dealer William Ohly that between 1947 and 1956 was home to some seventeen Australian artists and one art historian. Sydney artists Mary Webb, Robert Klippel and James Gleeson were the first to arrive, and soon after Webb held an exhibition at Ohly’s Berkeley Galleries in Mayfair in London. The abstract painter Webb was then in a group show at the Leicester Galleries, also in London, while Klippel and Gleeson, through the pioneering Belgian historian of Surrealism ELT Mesens, whom they met at the Abbey, were in a show at his and Roland Penrose’s London Gallery. The sculptor Klippel for his part travelled to France with Gleeson, where they met Surrealist patriarch André Breton in Paris, again through Mesens, then after leaving the Abbey in 1948 went on to live in another art colony, La Cité Fleurie on Boulevard Arago in Paris, where E Philips Fox, Ethel Carrick Fox and Stella Bowen had lived before and after the First World War, and would show at the prestigious Galerie Nina Dausette. The Surrealist Gleeson soon after left for Sydney, continuing his practice as a painter, but also working as an art critic, first for the Sun newspaper from 1949 and then for the Sun-Herald from 1962, where he provided a cosmopolitan alternative to the increasingly nationalist discourse of Australian art in the 1950s and 1960s. Klippel, returning to Australia in 1950 with his wife Nina Mermey, whom he had met in Paris, carried on working as a sculptor, before leaving once more to teach in America for some four years. Webb for her part never came back to Australia, moving permanently to Paris in 1949 after leaving the Abbey and continuing to work and exhibit there until her death in 1958, with another Belgian, the historian of twentieth-century abstract art Michel Seuphor, urging Australian galleries to acquire her work, something that would take some two decades to occur. On the other hand—to mention just two other Australians at the Abbey—the sculptor Graeme King would marry Inge Neufeld, who had fled Nazi Germany and together they would arrive in Australia in 1951, where the now Inge King would become one of Australia’s most important post-war sculptors.

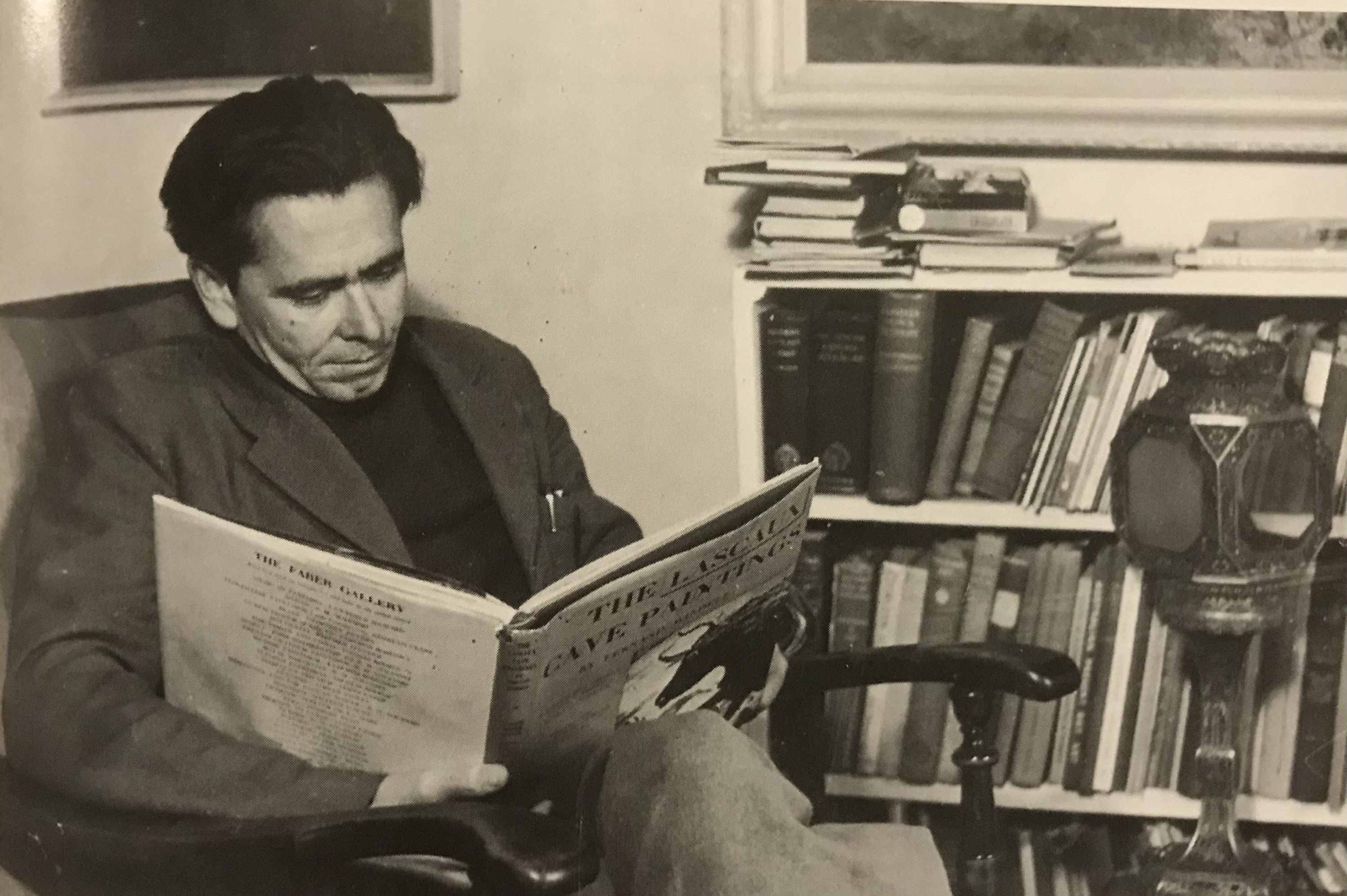

There were, that is to say, not only Australian artists at the Abbey, but artists from Central Europe, including, for example, the film director Carl Koch and the animator Lotte Reininger from Germany, the figurative painter Helen Grunwald and the jeweller and ceramicist Angela Varga from Austria and the draughtsman and black-and-white artist Marcel Frishman from Poland. All of these artists, as with the Australians, had interactions with British artists and can along with them be seen to be opening up a closed and nationalist post-war British art and art public to the outside, most notably in the popular arts:10 for example, Reininger’s silhouette animations of the 1960s were known to most British children, who would have seen her Cinderella or Puss in Boots, both from 1954, or her Hansel and Gretel or Jack and the Beanstalk, both from 1955. And in terms of the influence of Ohly himself and not only the artists who were gathered at his Abbey, there is the series of exhibitions he put on as part of his “ethnographic” collection at Berkeley Galleries in the mid 1940s under the title “The Art of Primitive People,” which—as with his showing of English sculptor Henry Moore together with the Nigerian painter Ben Enwonwu—can appear to be a precursor to the well-known 40,000 Years of Modern Art, held at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London in 1948, and even something like Jean-Hubert Martin’s landmark Magiciens de la terre at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 1989. Ohly took great pride in his collection, in which he freely mixed objects from different times and cultures, and he willingly shared it with the residents of the Abbey; and we might wonder what influence it had on the art historian Bernard Smith, who started writing his famous essay “European Vision and the South Pacific” while at the Abbey, and whose “Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner and Cook’s Second Voyage” derives from a similar showing of astronomer William Wales’ astrolabe to Samuel Taylor Coleridge while he was a schoolboy.11 On the other hand, we would also have to admit that Smith’s later “Antipodean Manifesto” of 1959 was influenced by his discussions with the Scottish painter and jeweller Alan Davie, who was staying at the Abbey at the same time as Smith and was, contra Smith, enthusiastic about the Jackson Pollock abstracts he had just seen at the 1950 Venice Biennale.

But we might also consider the Australians in those other English art colonies at Newlyn, St Ives, Newquay and Polperro, all in Cornwall on the south-east coast of England. The first of these is the once world-famous painter and illustrator Mortimer Menpes, whose Orientalist depictions of Japan inspired Oscar Wilde to write “life imitates art,” and who painted with the English Impressionists James McNeill Whistler and Walter Sickert over the course of 1883–4. Then there is Australia’s “lost Impressionist” John Russell, whose painting trip to Polperro in 1884 is almost the last thing he does in England before moving to the much bigger art colony of Montmartre in Paris. (We will come back to Russell in a moment.) There is the Heidelberg School David Davies, who offers painting classes at St Ives between 1898 and 1904 and teaches there the future Director of the National Gallery of Victoria JS McDonald. There is also the Heidelberg School Charles Conder, who painted his last plein air works at Newquay in 1906, and Richard Hayley Lever, whose “modified post-Impressionist picture” Winter St Ives (c. 1914), as the New York Herald called it,12 is in the Brooklyn Museum in New York, and who moved to America in 1912 at the urging of the Canadian-American landscape painter and member of the famed “The Eight” painting group Ernest Lawson. Hayley Lever then taught for more than a decade at the Art Students League in New York, and in 1924 was given the honour of painting the Presidential yacht for Calvin Coolidge. We leave this line of Australian Cornish artists—and, of course, our point here is how all of this complexifies the usual story of Australian Impressionism—with the sculptor Barbara Tribe, who began teaching at the Penzance School of Art after the War and continued to work there for over forty years before retiring in 1988, and the painter and long-time employee of the National Gallery of Victoria Kenneth Hood and his painting Cornish Harbour (1957), which is firmly of the third or even fourth School of St Ives, the one that is said, without irony, to have challenged the New York School of the 1950s.13

We might shift our attention now to France, the country with the most art colonies involving Australians and where Australian art’s connection with art colonies has been most recognised. We might begin on the coast of Brittany with the well-known Pont-Aven, where Menpes lived and worked for two years between 1881 and 1883, and where also the Melbourne Gallery School-trained Iso Rae completed her very Pont-Aven Girl with Goat (c. 1895), with its stylised Breton girl and goat set side-on in a pale silvery light in an elongated vertical format. As St Ives is to Newlyn, just ten kilometres up from Pont-Aven on the Atlantic Coast is the fishing town of Concarneau. It is here that over the years the New Zealand painter and teacher Frances Hodgkins brought her classes from Académie Colarossi in Paris and her fellow New Zealand plein airist Sydney Thompson resided for decades, during which time he completed hundreds of paintings of the port’s people and boats. The watercolourist Owen Merton, another New Zealander, also spent considerable periods there; and Concarneau is, at least from an Australasian perspective, dominated by New Zealand artists.14 And considerably further around the French coast in the Pas-de-Calais near the Belgian border is the seaside town of Étaples, whose Australian and New Zealand residents and visitors are the subject of French art historian Jean-Claude Lesage’s Peintres Australiens à Étaples. In it he makes clear the extent of Australian painters’ engagement with the art colony that began to develop there in the late nineteenth century. He counts as “les figures marquantes” of Étaples the Rae sisters, Isobel and Alison, who stayed there in 1895; Rupert Bunny, who also stayed in 1893, and then again in 1895, 1902 and 1907; Marie Tuck, who stayed in 1907 and 1908 (she subsequently took a séjour there every year from 1910 until 1914): Arthur Baker Clack, who stayed repeatedly from 1910; Hilda Rix, who stayed every summer from 1910 until 1917; as well as such “voyageurs” as Conder, E Phillips Fox, Eleanor Harrison, Alice Muskett and Winifred Honey. Altogether, we might say, to quote Lesage:

Australian painting conquers its identity at the same moment as its most brilliant exponents leave the country of their formation, of their free creation. Winning Europe over is, for many of them, an initiatory voyage into the world of art. Far from being mere epigones, their contact with European “pictorial revolutions” is the revelation of their proper aptitude, their real nature, as well as a formidable stimulant. And in this bubbling up of ideas, of theories, the real creators find their way and the material to be overcome.15

Indeed, between the wars, numerous Australian artists chose to work in many different French art colonies—and, again, as with Lesage, the task would always be to think how the experience shaped their practice and through that the shape of Australian art. For example, looking to shake off their academic training at the Julian Ashton Art School in Sydney, Grace Crowley, Dorrit Black and Anne Dangar all participated in the first-generation Cubist André Lhote’s inaugural summer school at Mirmande near the Rhône River between Valence and Montélimar in south-east France in 1927. It was a place that Lhote would continue to come back to with his students into the 1950s, and in so doing lent his considerable cultural cachet to the wider project of the post-war re-invigoration of crumbling French country towns. On the other hand, it was the ironic fate of many such art colonies that they would eventually become too expensive for the artists who originally “discovered” them. For her part, Black, having returned to Sydney in 1929 and founding the Modern Art Centre there in 1931, went back briefly to Mirmande in 1934, before returning permanently to Adelaide the next year, whereas Dangar, after coming back to Sydney in 1928, soon after made her way over to another first-generation Cubist, this time Albert Gleizes’, art colony, Moby-Sabata at Sablons-Serrières on the Rhône River, south of Lyon, where she was to remain for the rest of her life. While at Moly-Sabata, Dangar moved from painting to ceramics, and from the 1930s on she effectively becomes the potter of Cubism and incontestably one of the great French ceramicists of the twentieth century. And Dangar too was another expatriate that this time Crowley tried to have recognised and collected after her death, with it again taking some two decades for Australian galleries to do so.16

Also in the 1930s, the French-trained expatriate painter JW Power had two addresses in Paris. The first, at 13 bis rue Schoelcher, he had occupied since the studio-complex was finished in 1924. Very much an atelier for the well-heeled artist, the address was home to the writer Anaïs Nin in the 1920s, and after the war it became the life-long home of the philosopher and feminist Simone de Beauvoir and the long-time studio of the painter of the informel and the colour black Pierre Soulages. (Pablo Picasso had earlier lived in 5 bis rue Schoelcher from 1915 to 1916.) When he returned to Paris from Brussels following his now well-known exhibition with the artist group Abstraction-Création in 1934, Power took a studio in the complex at 31 rue Campagne-Première, the art colony where the Surrealist Man Ray had a studio for more than a decade and where just down the street at number 17 the great twentieth-century printmaker and teacher SW Hayter ran his art school Atelier 17. The street was also the home or studio to numerous other local and international artists between the wars, including the Italian Giorgio de Chirico, the Russian Wassily Kandinsky, the Japanese Tsuguharu Foujita and the French Nicolas de Staël (incidentally, a “student” of Power’s book Élements de la Construction Picturale), as well as the famous Hôtel Istria, whose long-term residents at one time or another included Marcel Duchamp, Tristan Tzara and Francis Picabia. It was perhaps the most famous artistic address in Montparnasse, and it was during these years that Power’s “social relations and political sympathies can be discerned from his friendships as much as from his participation in artist groups.”17

However, before concluding our abbreviated tour of the Australians in art colonies in France, it would be remiss of us not to come back to John Russell, who maintains a studio at the Villa des Arts in Montmartre from 1885 until 1921, which was a studio complex that was both an artistic and literary centre during this period. It was the place, after all, where Eugène Carriére painted his portrait of Paul Verlaine in 1890, where Pierre-Auguste Renoir painted his portrait of Stéphane Mallarmé in 1892 and where Paul Cézanne famously worked on the portrait of his dealer Ambroise Vollard over some one hundred and ten sittings throughout 1898–99 before finally abandoning it. For his part, Mallarmé put something of his experience of being painted by Renoir into verse in one of his “Les Loisirs de la Poste”:

At the Villa des Arts, near the avenue de Clichy,

paints Mister Renoir

Who before a bare shoulder,

Grinds something other than black.18

Subsequently, inspired by conversations with his close friend Vincent van Gogh and no doubt by his experiences at the Villa des Arts, Russell bought land and built a home on Belle-Île off the coast of Brittany in 1888 and established his own art colony there, naming it the ‘Studio of the Four Winds’. The art historian Ann Galbally calls it an “artist’s co-operative,” and describes it as a “complex of house, garden, studio and workshop.”19 It was not perhaps a true art colony because the numerous artists who stayed at or near Russell’s own house, known as the “Le Château Anglais,” did not do so at the same time. However, the French art historian Claude-Guy Onfray offers us an alternative art-historical way to understand Russell’s activities on Belle-Île in his essay “A Missed Appointment at Belle-Île for Van Gogh, or Did Russell Create the School of Kervilahouen?” In it, Onfray argues that there was indeed a School of painting centred around Russell named after the small nearby hamlet of Kervilahouen that runs from 1888 until Russell’s departure from the island in 1910, in which we have “a chain of friends that will follow one another on the island for one or two seasons.”20 Onfray further makes the point that the artist who benefitted most from the School is the future Fauvist Henri Matisse, who over the course of two stays during the summers of 1896 and 1897 discovered the possibilities of unmixed colour in a lesson Russell had originally learned from Claude Monet on the cliffs of Belle-Île some ten years earlier.

We might finish our brief history here by moving across the Atlantic and looking at the Australians involved in three art colonies in America: one on the west coast, one on the east coast and one more or less in the middle of the continent. The first we might turn to is the colony on the Monterey Peninsula in California, of which the near unknown, at least in Australia, Tasmanian Impressionist Francis McComas was a long-term resident. First arriving in America in 1898 via Hawai’i, McComas made his career initially in the Bay Area around San Francisco, and then moved a little further south to Carmel-by-the-Sea, where his reputation grew as his painting moved away from tonalism and toward a colourful version of Post-Impressionism. It was this work that led to his inclusion in the legendary Armory Show of 1913 as a representative of Californian art and to him organising, judging and showing in a place of honour at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1914. After the War, he was photographed by Dorothea Lange, built his own house and studio behind the famed Pebble Beach Golf Links (in fact, a keen golfer himself, he designed one of the bunkers on the fourteenth hole), worked with Cecil B. DeMille on the 1923 version of the film The Ten Commandments and began to paint the southwest of America, work that led him to being labelled, as the title of his 2020 retrospective at the Monterey Museum of Art has it, “California’s first modernist.”21

The second of our art colonies is over on the coast on the other side of America in Provincetown, Massachusetts, on the very tip of Cape Cod, where the Melbourne-born writer, educator and artist Mary Cecil Allen lived and worked from just after World War Two until her death in 1962. Like St Ives in England and Monterey in California, Provincetown originally grew at the end of a train line in the late nineteenth century, and at one time or another was home to everyone from the writers Eugene O’Neill and Norman Mailer to the painters Hans Hoffman and Robert Motherwell. Indeed, as early as 1916, the Boston Globe declared Provincetown to be the “biggest art colony in the world.”22 It was where America’s first-made millionairess, the Melbourne-born art collector and cosmetics empire founder Helena Rubinstein, once famously depicted by William Dobell, had a holiday home in the interwar years, and it is still a bustling cultural centre bringing together artists from all around the world. For her part, Allen first introduced abstraction into her work in response to Forum 49, a series of lectures on and exhibitions of abstract art in Provincetown in 1949, initiated by Adolf Gottlieb, who used to spend his summers there; and she would later write to her life-long correspondent, the Melbourne-based artist and art educator Frances Derham, that Provincetown was the “Mecca and marketplace for the new abstract expressionist and action painter.”23

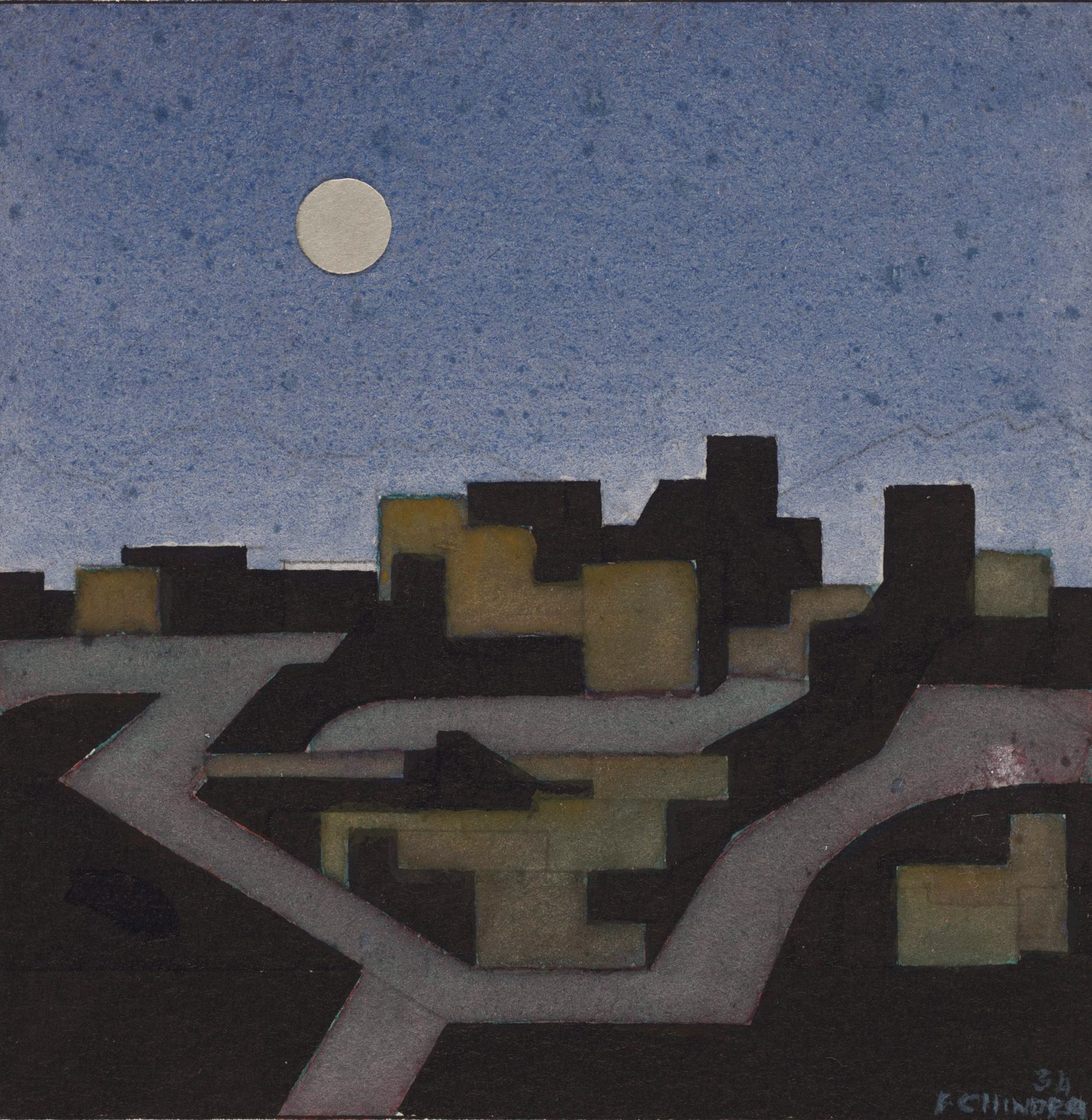

Finally, there is the almost equally famous art colony in Taos, New Mexico, which like many of the colonies we have discussed began life in the late nineteenth century. It was started there because of both its remoteness and its unique cultural situation, mixing as it does Americans, Mexicans and the Native American Pueblo Indians. In the 1920s, Francis McComas painted the Taos Pueblo, the famous communal buildings where the Puebloan people live, one and a half kilometres north of Taos, as did the painter and muralist Fred Leist and the New Zealand painter, physiotherapist and founder of the preventative medicine Sunlight League Cora Wilding. (Undoubtedly the best-known Taos residents during this time were the American painter Georgia O’Keefe and photographer Ansel Adams and the Russian portraitist Nicholas Fechin.) But for Australians, Taos was perhaps most important for the Sydney-born Frank Hinder and his New York-born wife Margel, who stayed there in 1933–34 as they made their way to Sydney from Boston and New York, where they had been living and working. They were part of the first summer school taught there by Hinder’s teacher at three institutions on the East coast and future stalwart of the community, Emil Bisttram, in what can be seen as something of a reprise of Crowley, Black and Dangar’s participation in that inaugural class held by Lhote at Mirmande. And undoubtedly both the Hinders brought back to Australia and Crowley, Ralph Balson and Rah Fizelle something of that “Transcendentalist” style developed by Bisttram and his colleagues, said to be inspired by the “limitless space,” “mystic quality of light” and “grandeur of the scenery” of the Taos desert landscape.24

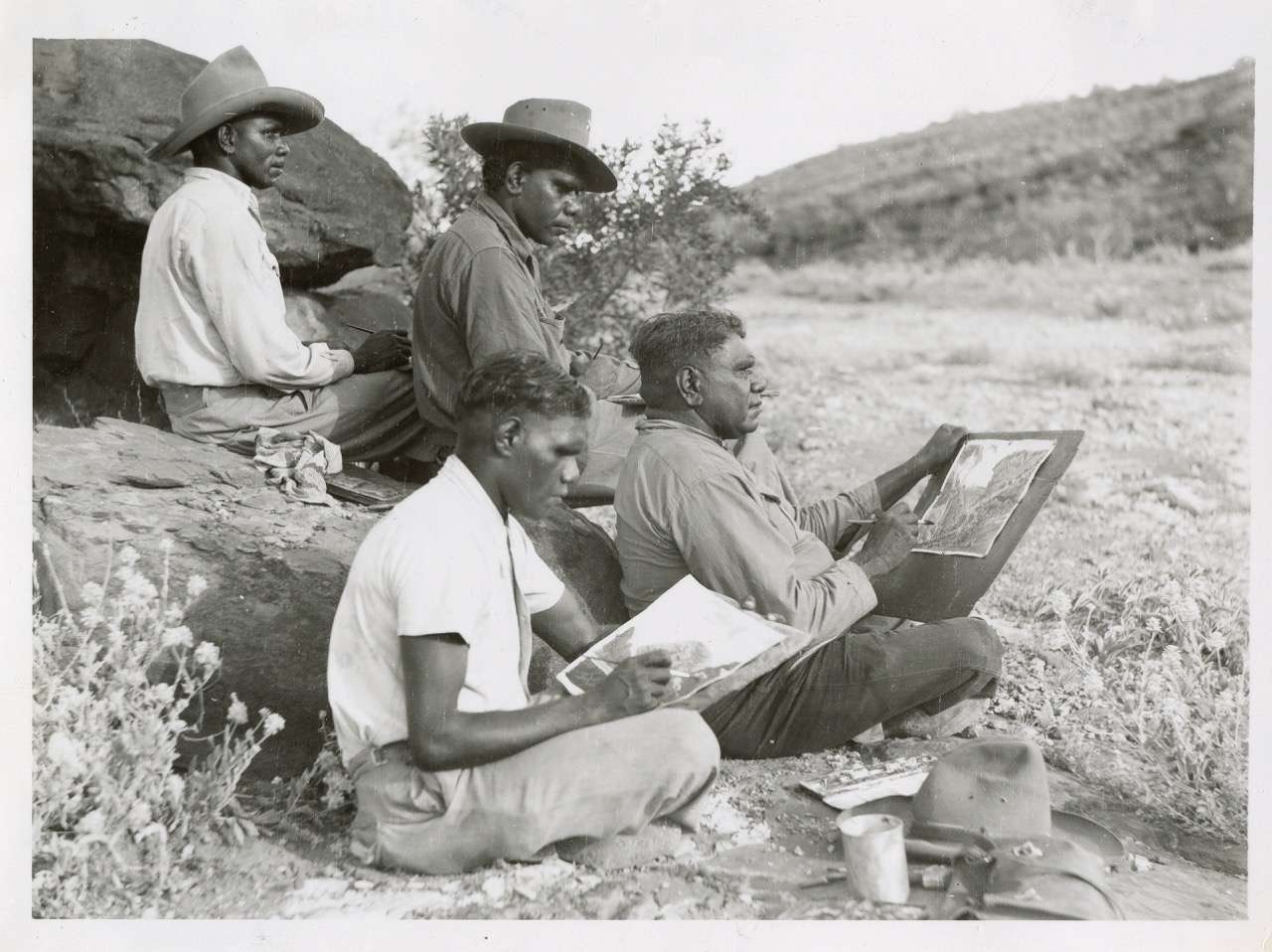

Indeed, we might compare Taos—continuously inhabited by the Puebloans for over a thousand years but occupied by the Spanish from the sixteenth century—to somewhere like Hermannsburg and its Lutheran mission in Central Australia, which might also be thought of as an art colony. Certainly, the artists Rex Battarbee and Frank Gardiner had the comparison between the two places in mind when they flipped a coin in 1928 to decide whether they would go to Taos or Hermannsburg, having seen Leist’s paintings of Taos at his show at the Fine Art Society Gallery in Melbourne the year before. The coin came down on the side of Hermannsburg, and not long afterward the two artists were travelling through the desert in their T-model Ford making watercolours of the landscape.25 It was this trip, of course, that led to Battarbee meeting the Arrernte man Albert Namatjira and then to the establishment of the Hermannsburg School of watercolour painting and ceramics, which still runs to this day. On the other hand, and to provide an alternative perspective, the English writer DH Lawrence’s coin, if he had tossed one, led him to Taos in 1922, where he took up painting, having been in Australia earlier that year, where he wrote his novel Kangaroo. But even before this post-war migration, Lawrence had written hopefully in a manifesto for a future art colony: “I want to gather together about twenty souls and sail away from this world of war and squalor and found a little colony where there shall be no money but a sort of communism as far as the necessaries of life go, and some real decency. It is to be a colony built up on the real decency which is in each member of the community.”26 And the Nobel Prize-winning Patrick White would set his great novel The Aunt’s Story (1948) partly in Taos, with his heroine—again, following that “Transcendentalism” the place was said to allow—mystically fusing with the landscape in the climactic final scene. White had originally visited Taos en hommage to Lawrence during a road trip he took around America in 1939. 27

The World’s Art Colonies in Australia

However, if we can find Australians in the world’s art colonies, we can also find the world’s art colonies in Australia. And if they were not because of our geographical isolation as full of artists from overseas as those overseas were as full of Australians, there were nevertheless instances of artists from overseas in our art colonies, and more than this the very idea of the art colony is international and already to connect Australia to places outside of itself. Of course, it is well known that “Australian” art began with the Heidelberg School and a series of “artist camps” in Box Hill (1885–6), Mentone (1886–7), Eaglemont (1888–9), Mosman (1890) and Curlew Camp (1891).28 And here we would want to suggest that it is at least in part Tom Roberts’ time spent with Russell in France in 1883 that allowed him to think the artist camp as a model for making art. Indeed, there were overseas artists who were both involved in and visited these artist’s camps, most notably the American cartoonist Livingstone Hopkins, who set up a camp in Balmoral with Julian Ashton, the Scottish novelist Robert Louis Stephenson, who stayed one night there, and the English-Australian Ada Cambridge, who partly set her novel A Marked Man (1891) there.29 But there have been a whole series of other colonies throughout the history of Australian art that have received individual treatment without anyone putting them together as a collective principle. There has been Murumbeena with Boyds of all generations from the 1910s on; Heide, overseen by patrons John and Sunday Reed, and housing Sidney Nolan, Albert Tucker, Joy Hester and John Perceval amongst others from the 1930s on; Warrandyte with Adrian Lawlor, Danila Vassilief and others, also from the 1930s; Lina Bryans’ so-called Pink House at Darebin, which housed Moya Dyring, Mary Cockburn Mercer, William Frater, Ada May Plante and Ian Fairweather at various points from the 1930s; Justus Jorgenson’s purpose-built Montsalvat in Eltham with Clifton Pugh, Helen Lempriere and even later the Rolling Stones from the 1930s; Nimbin on the northern New South Wales coast with Vernon Treweeke and others in the 1970s; and Wedderburn, just outside of Sydney, with Wendy Paramour, Elizabeth Cummings, John Peart and Suzanne Archer from the 1980s.

But there are perhaps two art colonies we might treat in greater detail here. The first is Merioola, the grand house in the Eastern suburbs of Sydney that housed a wide range of artists—but also dancers, musicians, architects and even mathematicians—thanks to its arts-loving landlady Chica Lowe from 1941 on. Among the first tenants were the curator Alleyn Zander, who had brought the important exhibition British Contemporary Art to Australia in 1933 and then worked for both the Royal Academy and Redfern Galleries in London; the Austrian sculptor Arthur Fleischmann, who arrived via Bali and would soon be giving the young Robert Klippel lessons; and the just graduated printmaker and sculptor Anne Weinholt. In 1945 the artistic couple Harry Tatlock Miller and Loudon Sainthill moved in, both released from military service at the end of the War. Miller, the future Director of the Redfern Galleries, had organised the Exhibition of Art for Theatre and Ballet, which featured work by Giorgio de Chirico, Ben Nicholson and Natalia Gontcharova, that toured Australia in 1940 and would soon put on the exhibition Australian Art for Theatre and Ballet, featuring a number of Merioola artists, including Jocelyn Zander, Alleyne Zander’s daughter. He and Sainthill had previously left Australia in 1939 with the departing Russian Ballet Company and travelled Europe before returning. After the War Miller would leave for London again with Sainthill, who would work as the set designer on any number of major British films, operas and theatre productions. But also taking up residence in 1945 were the newly decommissioned painters Donald Friend and Justin O’Brien and photographer Alec Murray and the young set designer Jocelyn Rickards, who would go on to work with Sainthill in London. 1946 saw the arrival of the Austrian Roland Strasser and the German Peter Kaiser fleeing war-torn Europe; and later there would be the Ukrainian Michael Kmit and the Polish George de Olszanski. But there was also a whole circle of regular visitors to and participants in Merioola’s activities, including William Dobell, Jean Bellette and Paul Haeflinger, as well as such American war artists as Edgar Kaufmann and Neil McEacharn, and such patrons as Treania Smith and Lucy Swanton from Macquarie Galleries. Indeed, by 1947, many of the Merioola artists had had a show at either the Macquarie Galleries or the David Jones Gallery, and in September of that year a Merioola group show was held in both Melbourne and Sydney. Gradually the group began to dissolve, and in 1951 Merioola itself was demolished. Although art history speaks of Merioola in terms of a neo-romantic Sydney “charm” school and even the return to religion with artists like Justin O’Brien, the curator of the 1986 Merioola and After exhibition Christine France emphasises the fact that there was no overall style and that either as returning expatriates or coming from overseas “most of the artists were internationally oriented yet, because of the war, cut off from any direct contact with other cultures. Their response to this situation was to turn their backs on the old authority of a more nationalistic naturalism and to concern themselves with style.”30

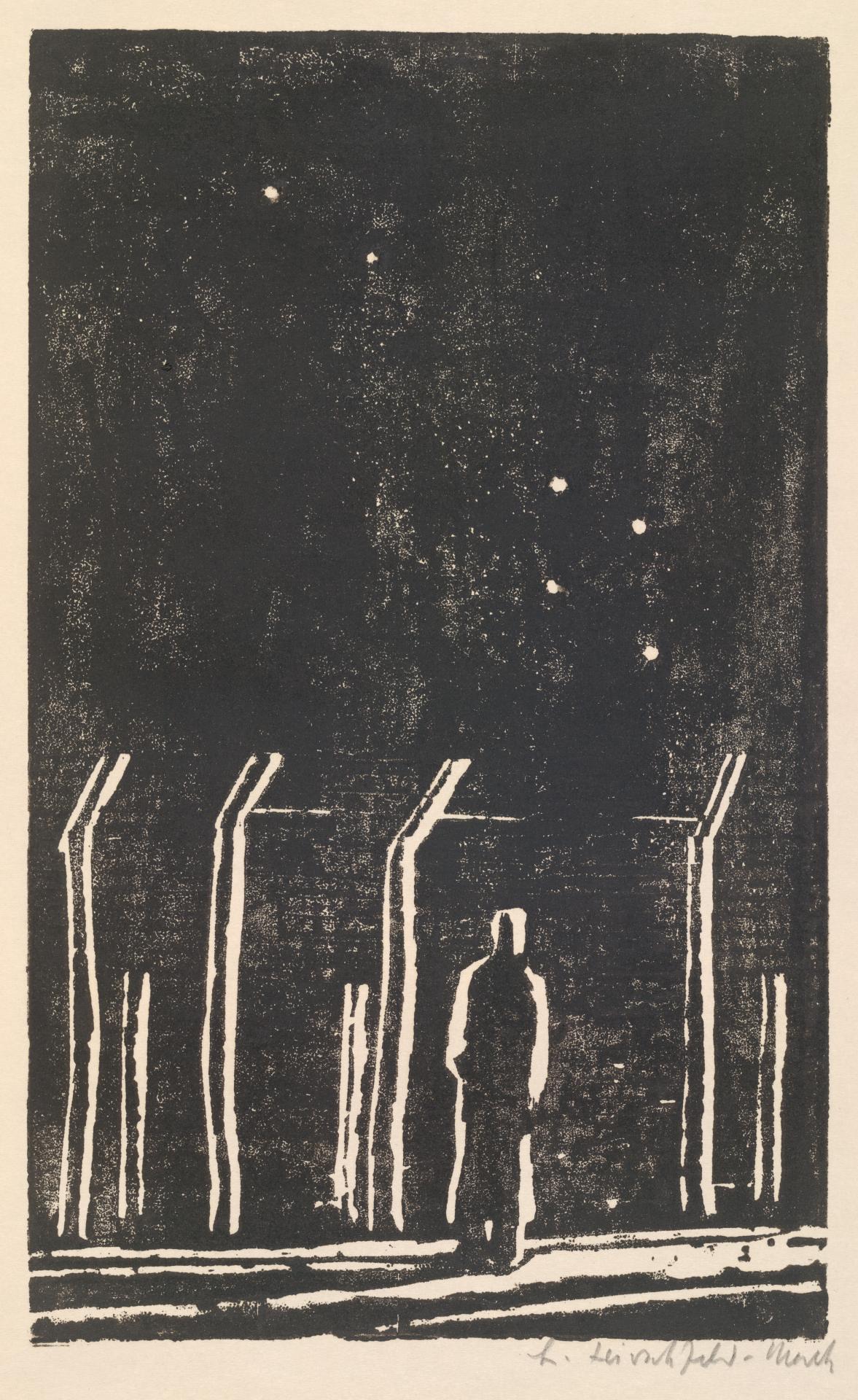

The other Australian art colonies we might speak of in some detail here are the internment camps established in Tatura in Victoria and Hay and Orange in New South Wales in 1940. (These camps were involuntary, much like the Aboriginal settlements we look at, but to consider them as art colonies is both to be faithful to what occurred there and to empower those held within them.) They were used to house the so-called Dunera Boys, some 2,542 male “enemy aliens” who were sent to Sydney from London on board the HMT Dunera, arriving in September 1940 after a gruelling fifty-seven-day voyage, during which, to quote the grandson of Sigmund Freud, Anton Freud, who was among them, “each man would have had an average of seven minutes per day to empty his bowels and bladder and peer through the only portholes not covered by iron plates.”31 Mostly German and Austrian Jews, the detainees were broadly cosmopolitan and well educated and a de facto university was set up in the camps and accomplished musicians set up orchestras with borrowed instruments, frequently playing the great German repertoire as an implicit rebuke against its appropriation by the Nazis. There were also a number of artists in the camps, and like the academics and musicians they soon set out to teach and train others in their practice. Most notably there was Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack, who had studied at the Weimar Bauhaus and taught at universities and academies in Weimar, Frankfurt and Berlin, and after the War would go on to work at the Geelong Grammar School, where he taught the prominent curator and Gallery Director Daniel Thomas, who himself was amongst the few Australian art figures at the time attuned to expatriate artists. But there was as well Klaus Friedeberger, who was taught by Hirschfeld-Mack and would go on to show with the Contemporary Art Society after the war. There was Erwin Fabian, similarly taught by Hirschfeld-Mack, who worked as a graphic designer in London in the 1950s, before returning to Australia and working as a sculptor. Finally, out of many others, we might mention Peter Kaiser, who had trained at the Berlin Academy between 1936 and 1938, and who as we know soon after being released from detention went to live at Merioola. But we also cannot resist mentioning here—reminding us perhaps of Loudon Sainthill—Hein Heckroth, who already had a reputation as a set designer in Germany and England before the war and upon being released from Hay following appeals from Herbert Read returned there to work eventually on Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s Oscar-winning Red Shoes in 1948. And there is as well the art historian Franz Philip, who was withdrawn from his University of Vienna doctorate on Mannerist portraiture in 1938 and sent to Dachau until his mother intervened and he obtained one of the last places on the Dunera. In 1947 he was appointed tutor in the Italian Renaissance at the University of Melbourne and in 1950 he became a Lecturer. Revealingly, many of the detainees in the camps were offered the opportunity to be repatriated to England as early as 1941, but a good number refused, having found a powerful sense of community in the camps. There have been several studies of the camps and those housed in them, but perhaps their character was best put by internee and eventual United States diplomat Klaus Loewald, who spoke of them as fashioning “little republics” in the Australian landscape.32

However, to conclude here, for us at least the ultimate consequence of the argument that art colonies are an essential but overlooked aspect of Australian art is that we might look again at Aboriginal art. For us, a number of the well-known art centres—to begin with Hermannsburg, but also Papunya and Yuendumu—can effectively be seen as art colonies. Of course, there is much that immediately appears to go against this. For example, it was not until 1976 with the passing of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act that Aboriginal communities could even claim the rights to land based on their continuous occupation. Nevertheless, we would also want to suggest that seeing Aboriginal art centres as colonies is to take them away from the national and to relate them to the international. It is to empower Aboriginal people, to give them a kind of autonomy, both from white Australian culture and even from their own inherited tribal identities.33 When schoolteacher Geoff Bardon, just to take Papunya as our example, gathered Pintupi, Luritja, Aranda and Anmatjira men together in the Great Painting Room in 1972, what we witness is a new form of sociality and creativity. Ideas are exchanged, stories are told, and something like a collective painting style that belongs exclusively to no one language group is developed. We witness a Central Desert “cosmopolitanism” that precisely demonstrates that “Australia” is not one single place:

I recall that after some months the painters would exchange banter about each other’s story or Dreaming and would ‘lend’ a story to each other, presumably after talking to the elders, so that these stories were able to be painted on acceptance, as it were. There was an interchange of stories between a Loritja, Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula, and an Anmatjira Aranda, Kaapa Tjampitjinpa, and also among the Anmatjira Aranda themselves; there was also considerable stylistic or story interchange between the Pintupi and other tribal groups.34

Reading this, we cannot but be reminded of an essay written by the American painter Anna Goates about her life at the famous Hôtel de Voyageurs in Pont-Aven, in which again there is a kind of community spirit that exceeds any of the individual participants and something is produced that could not happen if each worked alone:

Russia, Sweden, England, Austria, Germany, France, Australia and the United States were represented at our table, all as one large family, and striving towards the same goal… After lunch, on pleasant, sunny days, would follow the mid-day chat, as seated outside on hotel stoop and doorway, we leisurely sipped coffee and cognac… Criticism would be freely given and received; all were at liberty to say just what they pleased, and without any ill feeling. They were pleasant hours, indeed, spent around that Breton doorway and not wholly fruitless ones either.35

And is not something like the art colony the model for much contemporary art today? Consider the much-reproduced photograph of the South African art collective Breaking Bread gathered together with other artists sharing a meal at Brook Andrew’s acclaimed NIRIN Biennale of Sydney in 2020. The revolutionary aspect of Andrew’s iteration is that he did not merely import art from overseas—the usual model for Biennales, which serves only to emphasise our isolation and provincialism—but to the extent possible got artists to make work here in response to being in Australia and the presence of each other. (See, for example, Mexican artist José Davila’s The Act of Perseverance (2020), which incorporates materials found on Cockatoo Island, and the Australian-Papua New Guinean artist and art collective Eric Bridgeman and Haus Yuriyal’s SUNNA (Middle Ground) (2020), which was built and installed on Cockatoo Island.) As with those Desert art centres we looked at, to think NIRIN in terms of the art colony is not only to acknowledge the participating artists’ frequent status as belonging to colonialised peoples, but also to propose a kind of self-authorising secession from this colonised status, an exception or alternative to the prevailing national histories of art.36 Indeed, there were a number of writings that Andrew brought together in a reader that he made for the exhibition that pointed towards this model of the Biennale as an art colony. To begin with, there was Andrew’s own introductory “Yiradhu marang to all artists and collaborators,” in which he writes: “NIRIN focuses on many critical issues and pathways for action, reflecting on the environment and sovereignty as well as coming together. It is a place where creatives congregate and support communities, and collectively reflect and give visibility to the challenges we face.”37 Then Noongar yorga Native Title strategist Tamara Murdock writes in “Cutting Up Country and Counter-Mapping”: “Rather than continue to be rendered invisible and subject to territorialising processes, Country-based IPAs [Indigenous Protected Areas] enable the uprising of formerly subjugated peoples and knowledges and makes imposed boundaries less relevant.”38

Something of this thinking of art in terms of the art colony was also to be seen in 2018 at the National Gallery of Victoria’s Colony: Australia 1770–1861/Frontier Wars. The show was divided into two parts: on the bottom floor of NGV Fed Square was a history of European colonial art from first contact with Australia through to 1861 and the opening of what was later to become the NGV; and two floors above it were a number of works by contemporary Indigenous artists, frequently taking the colonial depiction of Indigenous Australians as their subject matter. The power of the exhibition lay in the way that the work by Brook Andrew, Gordon Bennett, Maree Clarke, Michael Cook, Julie Dowling and Julie Gough not only was about their own colonisation, but, as the title of the show indicates, saw Australia itself as a colony: a temporary, contingent, provisional collection of people momentarily working together in comparison to sixty thousand years of continuous inhabitation by Indigenous people.39 (How tenuous and fragile Nicholas Chevalier’s watercolour of The Public Library (1860) looked in relation to the art of Country around it.) Australian art, therefore, does not ultimately speak for anything “national,” but is just as particular and sometimes just as universal as that of an art colony. “Australian” art is as much as anything the art of an art colony, both here and overseas. And it is this that we have tried to do here by comparing the Abbey in New Barnet to Merioola in Sydney, to the prison camps of Tatura and Hay, to the Aboriginal art centres of Hermannsburg, Papunya and Yuendumu: to find another way of describing where “Australian” art occurs and in doing so find other places where it occurs. It would be no longer the art historians’ art history of single great artists, but the artists’ history of collaborative practice and the interaction with other artists. And if this can seem a very contemporary model of art, it can also be shown to have run throughout the whole period of modernism, as both an alternative to and even a secession from it. The history of Australian art is as much as anything a history of art colonies, as is the “national” history of any other country.

-

To take just three examples: George Collingridge launching Australian Art: A Monthly Magazine and Journal in 1888; Tom Roberts, Charles Conder and Arthur Streeton publishing a letter concerning the founding of a “great school of painting in Australia” in The Argus in 1889; and the opening of Exhibition of Australian Art at the Grafton Galleries in London in 1898. ↩

-

On the 9 x 5 Impression Exhibition as the “genesis” of Australian art, see the chapter “Genesis, 1885–1914” in Bernard Smith, Australian Painting (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 71–125. ↩

-

Wilf Douglas, An Introductory Dictionary of the Western Desert Language (Perth: Edith Cowman University, 1988), 193, https://ro.ecu.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=8117&context=ecuworks. For an essay on the “cosmopolitanism” and “transactional environment” of Western Desert painting, see Quentin Sprague, “Collaborators: Third Party Transactions in Indigenous Contemporary Art,” in Double Desire: Transculturation and Indigenous Contemporary Art, ed. Ian McLean (Newcastle-upon-Tyre: Cambridge Scholars Press, 2014), 71–90. ↩

-

See Doris Hansmann, The Worpswede Artists’ Colony (Munich: Prestel Verlag, 2011); Katherine Bourguignon, Impressionist Giverny: A Colony of Artists, 1885–1915 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007); Robert W. Edwards, Jennie V. Cannon: The Untold Story of the Carmel and Berkeley Art Colonies (Oakland: East Bay Heritage Project, 2012). ↩

-

See Adolf Fischer, “Die “Secession” in Japan,” Kunst für Alle: Malerei, Plastik, Graphik, Architektur, 15 (1899/1900): 321–6; Steve Shipp, American Art Colonies, 1850–1930 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996); and Elisabeth Fabritius, Danish Artists’ Colonies: The Skagen Painters, the Funen Painters, the Bornholm Painters, the Odsherred Painters (Denmark, Faaborg Museum, 2007). ↩

-

See on this Nina Lübbren, Rural Artists’ Colonies in Europe 1870–1910 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001). See also Lübbren’s essay ‘Breakfast at Monet’s: Giverny in the Context of European Artist Colonies’, in Impressionist Giverny, op. cit., 29–44. The other foundational transnational account of art colonies is Michael Jacobs, The Good and Simple Life: Artist Colonies in Europe and America (Oxford: Phaidon, 1985). ↩

-

Lübbren, Rural Artists’ Colonies, 2001, 7. ↩

-

Lübbren, Rural Artists’ Colonies, 2001, 9. ↩

-

Brian Dudley Barrett, Artists on the Edge: The Rise of Coastal Artists’ Colonies, 1880–1920 (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2010), 20. ↩

-

See on this Cheryl Buckley and Tobias Hochscherf, “Introduction: From German “Invasion” to Transnationalism: Continental European Émigrés and Visual Culture in Britain.” Visual Culture in Britain, Special issue “Transnationalism and Visual Culture in Britain: Émigrés and Migrants 1933 to 1956” 13, no. 2 (2012): 157–68. ↩

-

See Bernard Smith, “Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner and Cook’s Second Voyage,” in Imagining the Pacific: In the Wake of Cook’s Voyages (Carlton: Miegunyah Press, 1992), 135–71. The essay was originally published in the Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 19, nos. 1/2 (1956): 117–54. ↩

-

Cited in Carol Lowrey, Hayley Lever and the Modern Spirit (New York: Spanierman Gallery, 2010), 20. ↩

-

Chris Stephens, “The Art of St Ives is No Sideshow,” The Guardian, 10 May 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/may/09/tate-st-ives-modern-artists-localism. For the Australians at Newquay and St Ives, see Tracey Cooper-Lavery, Wild Colonials: Australian Artists and the Newlyn and St Ives Colonies (Bendigo: Bendigo Art Gallery, 2009). ↩

-

From a post-colonial perspective, of course, Australia and New Zealand are not so much irrevocably opposed national identities, but relatively close art colonies whose inhabitants often found themselves together. ↩

-

Jean-Claude Lesage, Peintres Australiens à Étaples (Étaples-sur-Mer: A.M.M.E. editions, 2010), 18. See also Lesage’s “L’École d’Étaples – un foyer artistic à la fin du XIX^e^ siècle,” La Revue de Louvre et des musées de France 51, no. 3 (Juin, 2001): 2. ↩

-

For an overview of Dangar, see Bruce Adams, Rustic Cubism: Anne Dangar and the Art Colony at Moly-Sabata (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004). ↩

-

ADS Donaldson and Ann Stephen, JW Power: Abstraction-Création, 1934 (Sydney: Power Publications, 2013), 30. After showing with the artist group Abstraction-Création in Paris in 1934, Power showed with Groupe d’artistes Anglo-Américains in 1935 and 1936, in the survey exhibition Origines et développement de l’art international indépendant at the Jeu de Paume in 1937, with the Salon Art Mural in 1935 and 1938 and, most notably, in the anti-Nazi protest show De Olympiade Onder Dictatuur in Amsterdam in 1936. ↩

-

Stéphane Mallarmé, ‘Les Loisirs de la Poste’, in Collected Poems and Other Verse (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 216 (translation amended). ↩

-

Ann Galbally, A Remarkable Friendship: Vincent Van Gogh and John Peter Russell (Carlton: Miegunyah Press, 2008), 199. ↩

-

Claude-Guy Onfray, “Un rendez-vous manqué de Van Gogh à Belle-Île, ou Russell a-t-il creé l’école de Kervilahouen?” Revue Chemins de Traverse, no. 51 (2017): 32. ↩

-

Robert J. Pierce, Francis McComas: Rediscovering California’s First Modernist: An Artist’s Biography and Catalogue (Monterey: Monterey Museum of Art, 2021). For an overview of McComas’ career and place within Californian art, see Scott A Shields, ‘Manufacturing Dreams: Francis McComas and California “Reductivism,” in Artists at Continent’s End: The Monterey Peninsula Art Colony, 1875–1907 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2006), 131–51. ↩

-

A.J. Philpot, “Biggest Art Colony in the World in Provincetown,” Boston Globe, August 27, 1916, http://www.provincetownhistoryproject.com/PDF/mun_000_1153-biggest-art-colony-in-the-world-boston-globe-1916.pdf. ↩

-

Letter from Mary Cecil Allen to Frances Derham, 11 September 1959; cited in Anne Rees, ‘Mary Cecil Allen: Modernism and Modernity in Melbourne 1935–1960’, emaj, 5 (2010): 1–136, http://doi.org/10.38030/emaj.2010.5.1. ↩

-

Emil Bisttram cited in Nancy Zimmerman, “Art and Soul,” Trend (Summer 2017): 57. ↩

-

On this coin toss, see the chapter ‘Taos or the Alice?’, in Martin Edmond, Battarbee and Namatjira, Penrith: Giramondo Publishing, 2016, 84–116. ↩

-

DH Lawrence in The Letters of DH Lawrence, vol. 2, June 1913-October 1916, eds. George J. Zytaruk and James T. Boulton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 259. ↩

-

If we had more time and space, we would speak about Conder and Gordon Coutts in Tangiers in North Africa, and then of Coutts building his house ‘Der Maroc’ in Palm Springs, California, at which he hosted everyone from Winston Churchill to Rudolph Valentino and helped start that town’s emerging art colony. We would also mention the Balearic island of Mallorca off the Spanish coast, where the New Zealander Len Lye lived for several months with the British literary couple Robert Graves and Laura Riding in the 1930s, before Frank Hodgkinson and Paul Haeflinger and Jean Bellette lived there from the 1950s until the 1970s, staying alongside the Australian-American Wallace Harrison, the renowned teacher of—at his New York 14th St School—amongst others: Charlotte Park, James Brooks and Helen Frankenthaler. And, to mention just two more out of many others, the British avant-garde rock musician Robert Wyatt and the Melbourne-born artist and musician Daevid Allen also resided for periods with Graves and Riding in the mid-60s. Finally, we might mention the 2015 McClelland Gallery exhibition Australian Artists in Bali: 1930s to Now, which included Ian Fairweather, Tina Wentcher, Adrian Feint, Vincent Brown and Arthur Fleischmann, amongst others. ↩

-

Here we should mention Helen Topliss, The Artists’ Camps: Plein Air Painting in Melbourne, 1885–1898 (Melbourne: Monash University Gallery, 1984); and Albie Thoms and Ursula Prunster, Bohemians of the Bush: The Artists Camps of Mosman, Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 1991). ↩

-

On Livingstone Hopkins, see Nick Dyrenfurth and Marian Quartly, ‘“All the World Over”: The Transnational World of Australian Radical and Labour Cartoonists’, particularly on Hopkins’ cartoon of the confrontation between ‘Labour’ and ‘Capital’ with regard to the August 1890 strike involving miners and shearers, in Drawing the Line: Using Cartoons as Historical Evidence, eds. Marian Quartly and Richard Scully (Melbourne: Monash University Press, 2009). In general, we would say there is work to be done on the connection between Hopkins’ pro-labour cartoons and Roberts’ Shearing the Rams (1888–90). ↩

-

Christine France, Merioola and After (Sydney: S.H. Ervin Gallery, 1986), 6. ↩

-

Anton Freud cited in Ken Inglis, “From Berlin to the Bush,” The Monthly (August 2010): 53. ↩

-

Klaus Loewald, cited in Ken Inglis, Suemas Spark and Jay Winter, Dunera Lives, Vol. 1: A Visual History (Melbourne: Monash University Press, 2018), xix. ↩

-

We are conscious of the potential provocation of what we are saying here, but we would want to oppose the art colony to colonialism in suggesting that the art colony—if that is what Hermannsburg, Papunya and Yuendumu can be considered as—has always stood against the national and its accompanying principle of colonisation. This would be something of the double meaning of “colony” that we are playing on in this essay. Indeed, altogether we would want to think “colony” in relation to empire, insofar as it is empires that both have colonies and historically were the first to house art colonies. ↩

-

Geoff Bardon and James Bardon, Papunya: A Place Made After the Story: The Beginnings of the Western Desert Painting Movement (Carlton: Miegunyah Press, 2018), 25. ↩

-

Annie Goater, “A Summer in an Artistic Haunt,” Outing 7, no. 1 (1885): 10–11. Cited in Rural Artists Colonies, 26–7. ↩

-

We are tempted to think NIRIN, which translates as “edge,” together with Brian Dudley Barrett’s Artists on the Edge, which is a study of the art colonies found around the coasts of Europe and particularly the North Sea, especially insofar as Andrew can bring together in his Biennale the Nordic Sami collective Suohpanterror with Yolŋu cultural knowledge from North East Arnhem Land in The Mulka Project. ↩

-

Brook Andrew, ‘Yiradhu marang to all artists and collaborators’, in Nirin Ngaay, eds. Stuart Geddes and Trent Walter (Sydney: Biennale of Sydney, 2020), np. ↩

-

Tamara Murdock, “Cutting Up Country and Counter-Mapping,” in Nirin Ngaay, np. Other relevant texts there for thinking NIRIN in terms of the art colony include Léuli Eshräghi, “Privilégier le plaisir autochtone”; Barbara Glowczewski, “Guattari and Anthropology: Existential Territories among Indigenous Australians”; and Jiva Parthipan and Paschal Daantos Berry, “Centring NIRIN – Art by Communities as the PRACTICE”. ↩

-

Joseph Pugliese writes of Julie Gough’s Locus (2006), which was in the exhibition after previously being installed at the 15^th^ Biennale of Sydney: “Gough’s 2006 installation at the Biennale of Sydney, Locus, can be seen to be working to resituate the Tasmanian Frontier Wars within a larger transnational context… Gough stages, in other words, her own act of ‘radical re-examination of the Tasmanian Wars’: the seamless chronology of coloniser history, and its triumphalist narrative of civilisational progress, has been rendered into discontinuous fragments that are compelled to bear witness to an Aboriginal re-envisioning of colonial history.” In Cathy Leahy and Judith Ryan (eds.), Colony: Australia 1770–1861/Frontier Wars (Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2018), 284; 286. ↩

Rex Butler teaches Art History at Monash University in Melbourne. A.D.S. Donaldson is a Lecturer in Painting at the National Art School in Sydney. Together they have recently co-authored UnAustralian Art: 10 Essays on Transnational Art History (Sydney: Power Publications, 2022).

Bibliography

- Adams, Bruce. Rustic Cubism: Anne Dangar and the Art Colony at Moly-Sabata (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004).

- Bardon, Geoffrey and Bardon, James. Papunya: A Place Made After the Story: The Beginnings of the Western Desert Painting Movement (Carlton: Miegunyah Press, 2018).

- Barrett, Brian Dudley. Artists on the Edge: The Rise of Coastal Artists’ Colonies, 1880–1920 (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2010).

- Bourguignon, Katherine. Impressionist Giverny: A Colony of Artists, 1885–1915 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007).

- Buckley, Cheryl, and Hochscherf, Tobias. “Introduction: From German “Invasion” to Transnationalism: Continental European Émigrés and Visual Culture in Britain.” Visual Culture in Britain, Special issue “Transnationalism and Visual Culture in Britain: Émigrés and Migrants 1933 to 1956” 13, no. 2 (2012): 157–68.

- Cooper-Lavery, Tracey. Wild Colonials: Australian Artists and the Newlyn and St Ives Colonies (Bendigo: Bendigo Art Gallery, 2009).

- Donaldson, A.D.S., and Stephen, Ann. JW Power: Abstraction-Création, 1934 (Sydney: Power Publications, 2013).

- Douglas, Wilf. An Introductory Dictionary of the Western Desert Language (Edith Cowman University, 1988).

- Edwards, Robert W. Jennie V. Cannon: The Untold Story of the Carmel and Berkeley Art Colonies (Oakland: East Bay Heritage Project, 2012).

- Fabritius, Elisabeth. Danish Artists’ Colonies: The Skagen Painters, the Funen Painters, the Bornholm Painters, the Odsherred Painters (Denmark, Faaborg Museum, 2007).

- Fischer, Adolf. “Die “Secession” in Japan.” Kunst für Alle: Malerei, Plastik, Graphik, Architektur, 15 (1899/1900): 321-6.

- France, Christine. Merioola and After (Sydney: S.H. Ervin Gallery, 1986).

- Galbally, Ann. A Remarkable Friendship: Vincent Van Gogh and John Peter Russell (Carlton: Miegunyah Press, 2008).

- Geddes, Stuart and Walter, Trent (eds.). Nirin Ngaay (Sydney: Biennale of Sydney, 2020).

- Goater, Annie. “A Summer in an Artistic Haunt.” Outing 7, no. 1 (1885): 10–11.

- Hansmann, Doris. The Worpswede Artists’ Colony (Munich: Prestel Verlag, 2011).

- Inglis, Ken. “From Berlin to the Bush.” The Monthly (August 2010): 48–53.

- Inglis, Ken, Spark, Suemas, and Winter, Jay. Dunera Lives, Vol. 1: A Visual History (Melbourne: Monash University Press, 2018).

- Jacobs. Michael. The Good and Simple Life: Artist Colonies in Europe and America (Oxford: Phaidon, 1985).

- Lawrence, D.H. The Letters of DH Lawrence, vol. 2, June 1913–October 1916. Edited by George J. Zytaruk and James T. Boulton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

- Leahy, Cathy and Ryan, Judith (eds.). Colony: Australia 1770–1861/Frontier Wars (Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2018).

- Lesage, Jean-Claude. Peintres Australiens à Étaples (Étaples-sur-Mer: A.M.M.E. editions, 2010).

- Lesage, Jean-Claude. “L’École d’Étaples – un foyer artistic à la fin du XIX^e^ siècle.” La Revue de Louvre et des musées de France 51, no. 3 (Juin, 2001): 2.

- Lowrey, Carol. Hayley Lever and the Modern Spirit (New York: Spanierman Gallery, 2010).

- Lübbren, Nina. Rural Artists’ Colonies in Europe 1870–1910 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001).

- Mallarmé, Stéphane. Collected Poems and Other Verse (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).

- McLean, Ian (ed.). Double Desire: Transculturation and Indigenous Contemporary Art (Newcastle-upon-Tyre: Cambridge Scholars Press, 2014).

- Onfray, Claude-Guy. “Un rendez-vous manqué de Van Gogh à Belle-Île, ou Russell a-t-il creé l’école de Kervilahouen?” Revue Chemins de Traverse, 51 (2017): 15-34.

- Philpot, A.J. “Biggest Art Colony in the World in Provincetown.” Boston Globe, August 27, 1916, <provincetownhistoryproject.com/PDF/mun_000_1153-biggest-art-colony-in-the-world-boston-globe-1916.pdf>.

- Pierce, Robert. J. Francis McComas: Rediscovering California’s First Modernist: An Artist’s Biography and Catalogue (Monterey: Monterey Museum of Art, 2021).

- Quartly, Marian, and Scully, Richard (eds.). Drawing the Line: Using Cartoons as Historical Evidence (Melbourne: Monash University Press, 2009)

- Rees, Anne. “Mary Cecil Allen: Modernism and Modernity in Melbourne 1935-1960.” emaj 5 (2010): 1–36, <doi.org/10.38030/emaj.2010.5.1>.

- Shields, Scott A. Artists at Continent’s End: The Monterey Peninsula Art Colony, 1875–1907 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2006).

- Stephens, Chris. “The Art of St Ives is No Sideshow.” The Guardian, 10 May 2014, <theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/may/09/tate-st-ives-modern-artists-localism>.

- Steve Shipp, American Art Colonies, 1850–1930 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996).

- Smith, Bernard. Australian Painting (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001).

- Smith, Bernard. Imagining the Pacific: In the Wake of Cook’s Voyages (Carlton: Miegunyah Press, Carlton, 1992).

- Smith, Bernard. “Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner and Cook’s Second Voyage,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 19, nos. 1/2 (1956): 117–54.

- Thoms, Albie, and Prunster, Ursula. Bohemians of the Bush: The Artists Camps of Mosman (Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 1991).

- Topliss, Helen. The Artists’ Camps: Plein Air Painting in Melbourne, 1885–1898 (Melbourne: Monash University Gallery, 1984).

- Zimmerman, Nancy. “Art and Soul.” Trend (Summer 2017): 55–63.