Anthony Mannix Secessions from Systems

I. Refusing Any Annexation

The Australian artist Anthony Mannix (1953–) has been publishing and exhibiting his writings, artworks, and artist’s books since the early 1980s. As a self-taught artist with lived experience of diverse mental health, or what Mannix prefers to call “mixed realities,” a question has been asked repeatedly of his work: is it connected to the broader conventions, institutions, and networks which make up the contemporary art world?1

For Mannix’s earliest champions, the answer to this question was entirely in the negative. Rosemary Jeffers and Terence Relph, who ran the Outsider Gallery in Sydney, argued in 1982 that works like Mannix’s, which they described as “a pure example of outsider art,” were disconnected from the “borrowed symbols and marks” that constitute the history of art.2 Because they are created “without reference to these established art forms,” the gallerists explained, such works “represent a degree of creativity that is often lacking in the welter of eclectic art styles by professional artists.”3 In making these arguments, Jeffers and Relph were adopting the views of twentieth-century theorists such as Roger Cardinal who, in his 1972 book Outsider Art, maintained that works by people with experience of diverse mental health, disability, and/or social marginalisation were completely removed from the inherited history of culture and its networks.4 They were also influenced by Herbert Eckert, who in 1981 argued that such artists were so isolated that it would be “a mistake to assume that the authors of this art are operating in opposition to the fine art system.”5 From this perspective, artists like Mannix would be incapable of manifesting any conscious resistance to the existing structures supporting contemporary art.

This understanding of art by people with experience of diverse mental health, with its stark binaries of inside and outside the art world, has been significantly challenged in recent years. As scholars like David MacLagan have shown, such artists are never disconnected from their broader social sphere, whether from its artistic conventions, its professional institutions, or its industrial contexts.6 To take the case of Mannix, he was not isolated but informed about contemporary developments in art, literature, and society. For example, not long after studying anthropology at Macquarie University in the late 1970s he encountered reproductions of art from Africa and New Guinea, and a discussion of so-called “outsider artists,” in a Sydney-based literary journal.7 Although there were years when the artist “lived in quite an isolated fashion,” he also noted that “I was influenced by all the outsiders, especially their techniques.”8 In this sense, his work developed in relationship with his understanding of the documented history of contemporary art, including the established discourse of outsider art itself.

Furthermore, Mannix’s work is demonstrably connected to the social, industrial, and professional networks that he has engaged with throughout his career. These have included, for example, enthusiasts of art by people experiencing marginalisation, including the American-born, Australian poet Philip Hammial. During the 1980s, his work also developed alongside and within a number of artist-run initiatives in Sydney where some of Mannix’s exhibitions were held. Moreover, as an artist who has spent periods in psychiatric hospitals, Mannix’s work is closely related to, and sometimes takes as its subject, the New South Wales mental health system. Accordingly, the idea which pervaded the earliest publications about Mannix’s work, that he was completely sealed off from his social and institutional context, began to be contested in subsequent accounts.

In 1989 the anthropologist Ulli Beier commented on what he perceived as the “ironies” that “there are now ‘outsider artists’ who write about and promote ‘outsider art.’” Noting Mannix’s co-founding of The Australian Collection of Outsider Art, Beier asks:

Is a self-conscious “outsider artist” not a contradiction in terms? And at what stage does a genuinely original vision become a “style”?… And when Outsider Artists hold joint exhibitions and swap each others’ work – can we still talk of “Outsider Art” or has this become a new counter culture?9

Mannix is an artist with an understanding of several traditions of art who has strived to promote the work of artists like himself. Far from an occasion for irony, this means that Mannix’s work can be seen in the light of his experience of diverse mental health and his engagement with a broad range of artistic and institutional contexts. As I argue in this article, the nature of this engagement has seen the artist participate in a series of deliberate withdrawals and secessions from established traditions of visual art in which the distinctions between the interior and exterior of the human figure are rigidly maintained; and from mainstream institutions—defined here as large, state-funded museums and prestigious commercial galleries which exhibit only a small number and a narrow range of artists. At the same time, as I will show, Mannix was positioned, and positioned himself inside certain exceptional institutions, including the pre-existing traditions of outsider art, and the relatively new enterprises known as “artist-run initiatives.”

Mannix’s interest in traditions of art which rebelled against conventions; his efforts to set up novel exhibition structures within which his work could be appreciated; and the acerbic critiques within his work of the mental health system—these are understood in what follows as forms of secession through which the artist sought to establish alternative institutions and paradigms for the production and reception of his art: in other words, a form of “counter culture.” The spirit in which we might understand his work was, therefore, aptly expressed in the title of an exhibition at Wollongong City Gallery in which the artist participated in 1992: “Refusing Any Annexation.”10 The ultimate object of Mannix’s many withdrawals and refusals was the negative, exclusionary structure perpetuated by certain traditions, institutions, and frameworks in both the art and health sectors, in favour of a radical affiliation with the principles of inclusivity and positivity.11

II. Methods

Mannix’s oeuvre speaks, as the artist has frequently argued, to a life lived with diverse mental health.12 As he has written, “my artistic output over the last twenty-five years has had one point and that has been to document the landscape of psychosis and the unconscious.”13 In 1994 the artist reflected on his experience as follows: “During psychosis Perception alters. In ‘sane’ time something might be perceived to be big, heavy, bulky, dark-coloured, and immobile. During a Psychosis the same might be registered as, without limit… animate and therefore immensely mobile.”14 In addition to this altered sense perception, Mannix notes, there is a merging between the material and the immaterial, between the apparent and the real: “It seems. And in seeming it becomes.”15 From this principle, Gareth Jenkins has argued that Mannix’s writing gives expression to the concept of “lived metaphor,” in which the imagination becomes the basis for reality.16 Although this can be a source of mental anguish—producing an experience that the artist once described as a form of “molten horror”—Mannix frequently emphasises the productive aspect of psychosis.17 This is true for the artist, especially, but not exclusively, when considered from an artistic perspective.

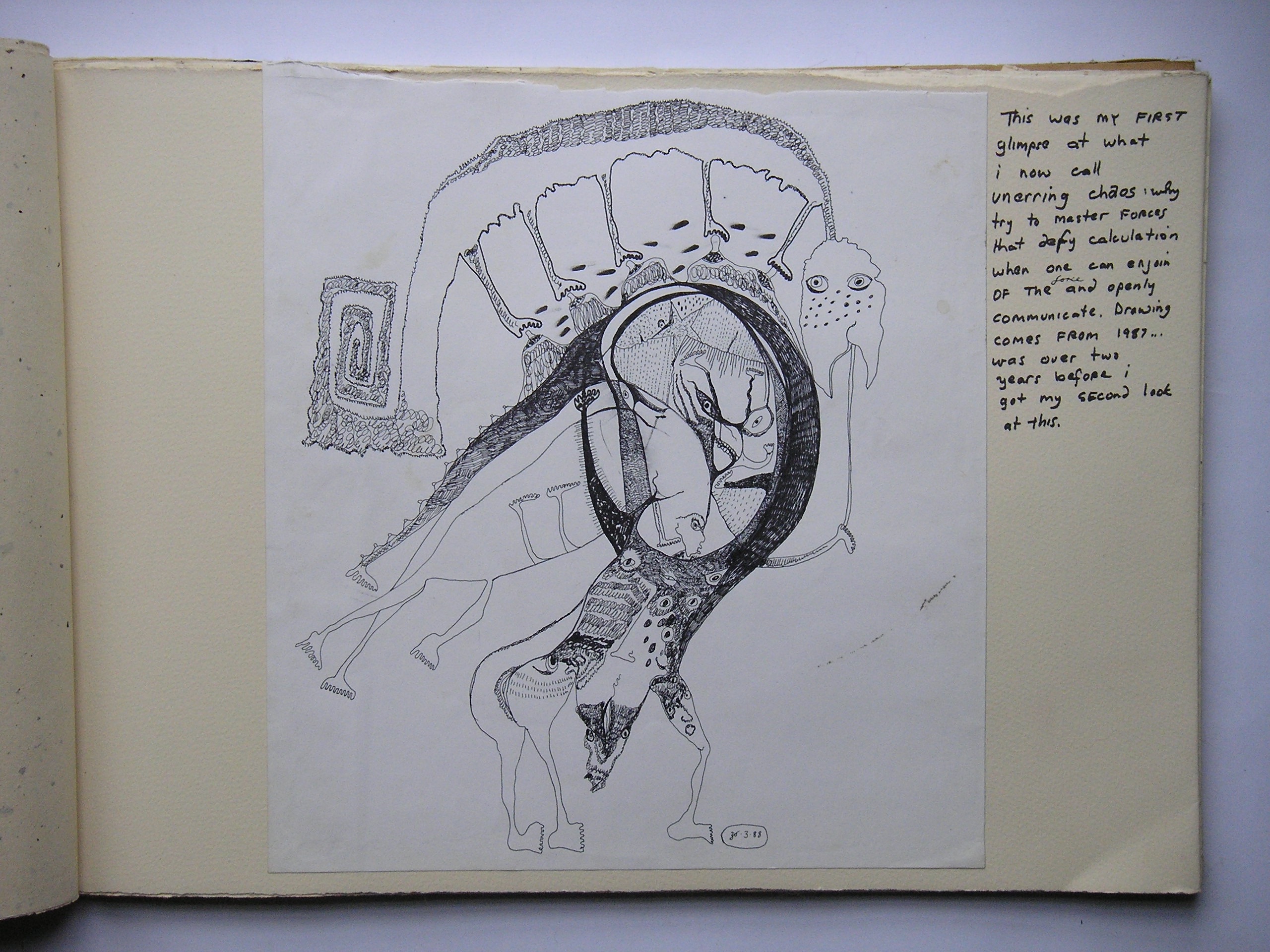

For example, a drawing that he completed in 1988, which is executed in fine ink pen with highly detailed, intricate patterning, shows a multi-legged creature, with faces on its torso and limbs, which is intertwined with several other animals and personages (fig. 1).18 The latter includes one which stands atop the assemblage of beings, teetering on a series of nipples like a diabolical lizard tormenting what lies underneath. The image has all the hallmarks of a terrifying phantom; and yet the artist notes in an inscription that “This was my first glimpse of what I now call unerring chaos: why try to master forces that defy calculation when one can enjoin of the force and openly communicate.” Elsewhere the artist has commented, in a similar vein, that “The great communiqué of madness is that it presents… in a plethora and with that the regard for life increases.”19 In light of these remarks, we can view the 1988 drawing not as a grotesque, ghoulish phenomenon, but as the sign of a heedless, proliferating form of metamorphosis that can be valorised for its multiplicity and sheer abundance. As Mannix has continually stressed, he conceives of his idiosyncratic mental experience not as an error or deficiency which needs correcting by the medical profession, but as a plentiful source of positive energy.

When one considers the abuse which the artist suffered at the hands of psychiatric institutions from the 1970s to the 1990s—about which more detail is provided below—it is important to do justice to the artist’s experience of diverse mental health in coming to an appreciation of the images that he produced. The methodology adopted here is grounded in the assumption that a fuller appreciation of Mannix’s art also requires us to investigate the significant parallels between these works and the world surrounding him, and to appreciate the broader professional and industrial spheres into which his art has been drawn. In what follows, I focus on two bodies of Mannix’s work: a number of drawings executed in the mid-1980s, and a series of artist’s books dating from 1989 to the present day.

III. Drawings

In 1984, Mannix was introduced, through Terrence Relph and Rosemary Jeffers, to Philip Hammial, with whom he would subsequently collaborate on numerous occasions.20 One of their earliest joint projects was a book titled Vehicles which included a series of works by the artist alongside Hammial’s writing.21 The images which Mannix produced in this period, including those reproduced in Vehicles, draw upon a rich and complex range of art historical sources. As I will argue, many of the artists who were important to Mannix in this period were themselves in a fraught or antagonistic relationship with existing traditions of art and its institutions, and thus served as important exemplars of how an artistic secession or withdrawal might manifest visually.

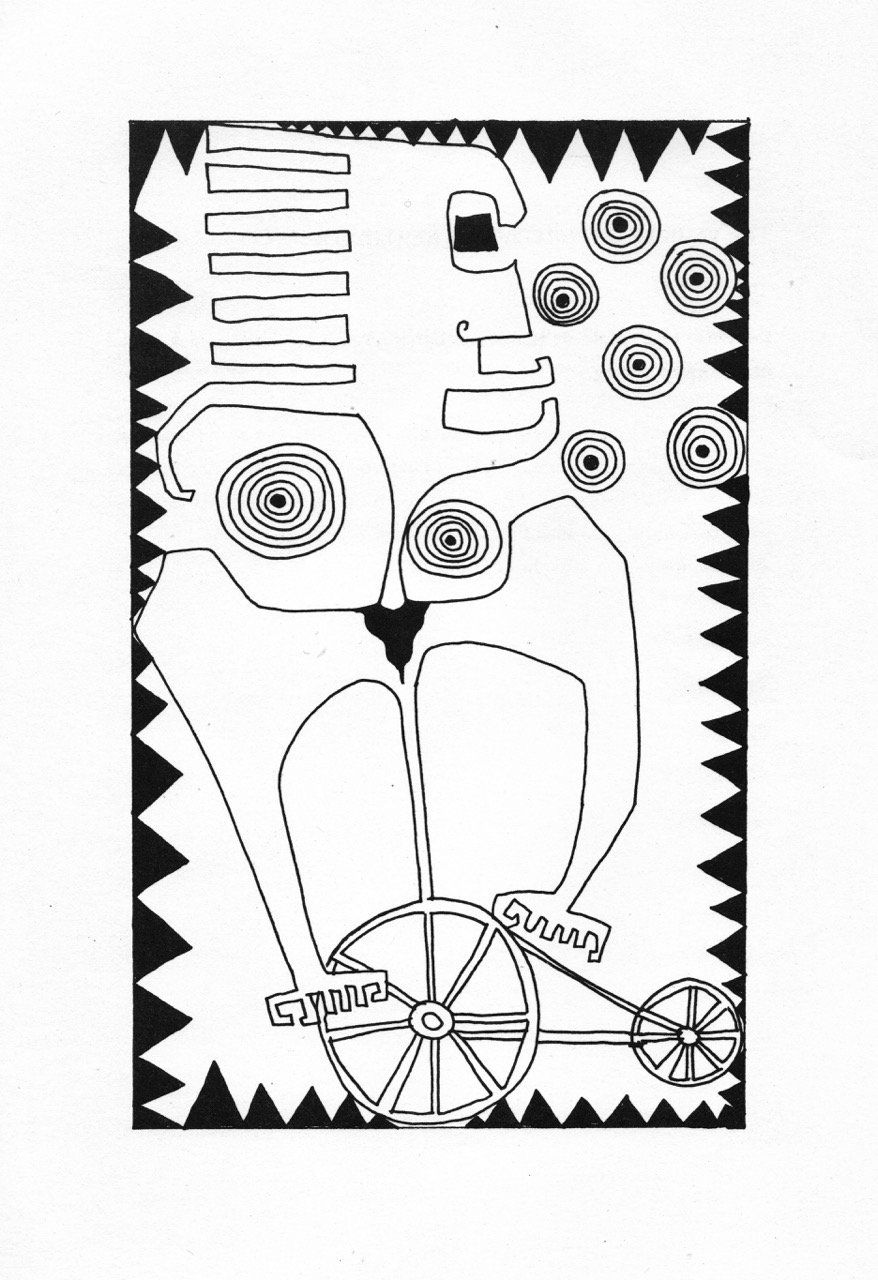

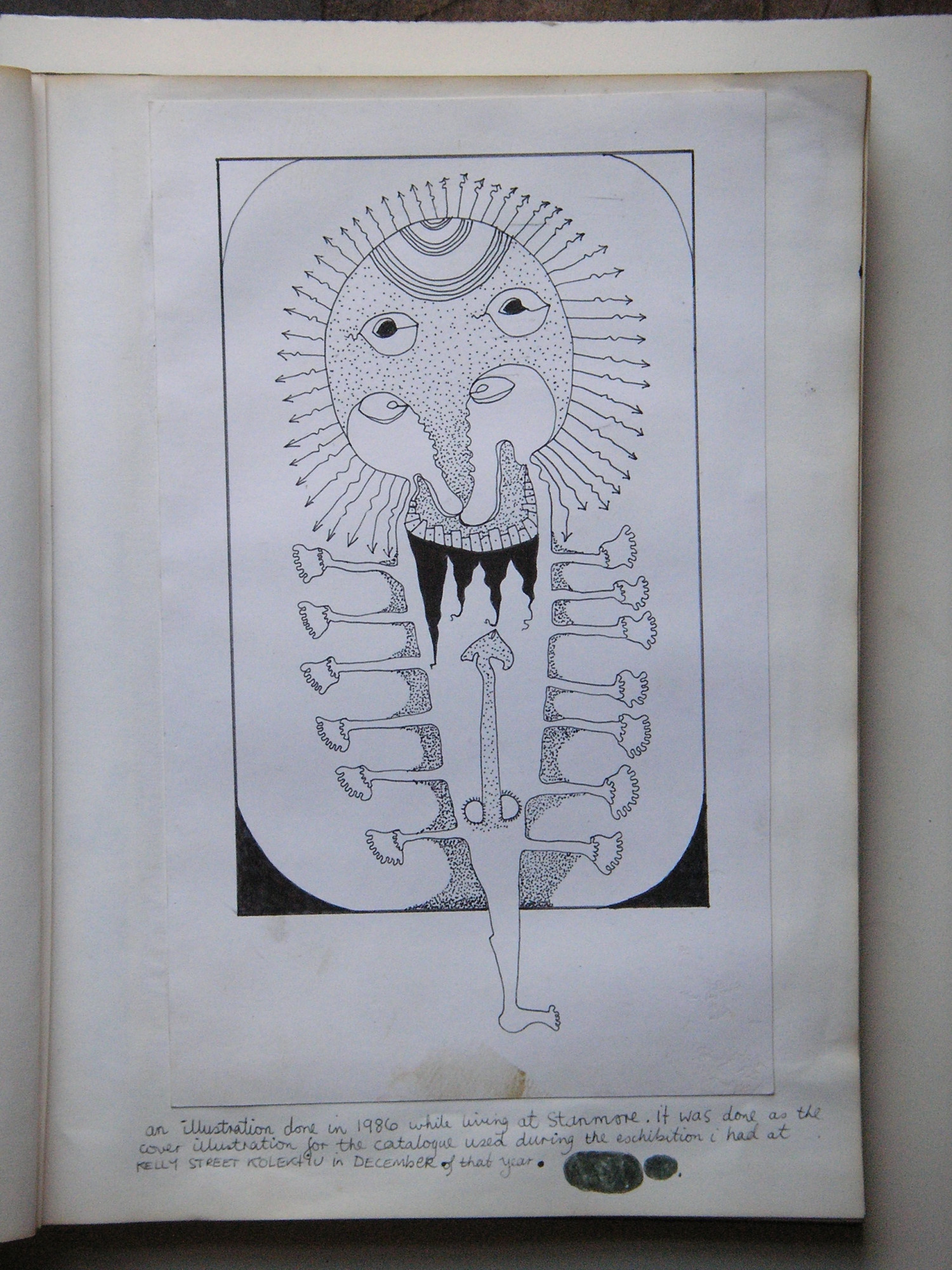

One notable reference for Mannix’s work in this period included modern printmaking from New Guinea, which he read about in a 1978 essay by Georgina Beier titled “Outsider Art in the Third World.”22 The article had a significant impact on Mannix when he first encountered it, leading him to read it over several times.23 The illustrations, including one by the New Guinea artist Barnabas India, feature stark black-and-white contrasts of zigzag shapes, and figures with distended limbs and gaping mouths, characteristics which are also visible in Mannix’s subsequent work, as in the image accompanying “The Vehicle of Equivocal Transfiguration” in Vehicles (fig. 2).24 Beier’s argument was that artists like India, an internal emigrant uprooted from his origins in the traditional cultures of highland New Guinea who had settled in the urban centre of Port Moresby, was “free from the restraints of religious function, artistic convention, and cultural conditioning,” and “became an artist more or less by accident.”25 This reflected Mannix’s own career as an artist, which had begun suddenly, without the benefit of formal artistic training.26 What also likely impressed Mannix about this article was Beier’s discussion of the notion of “proliferation” in the work of India: “Hands and faces begin to appear in the most unlikely places; men merge with birds or crocodiles or flowers.”27 These qualities can be observed in Mannix’s work, such as a drawing from 1986 which shows a figure with animal- or insect-like anatomy, multiple feet, and a halo of quivering arrows emanating from its head (fig. 3).28 Mannix’s interest in the work of artists from New Guinea was not an instance of primitivism, in which modernist artists characteristically sought to invigorate their art by appropriating the work of non-Western artist they considered totally at odds with their own. Rather, Mannix’s use of intense visual profusion was a means of identifying himself and his work with these very same qualities in the work of artists, like India, whose connections to existing structures and traditions of art had been attenuated or ruptured by migration, colonisation, and the experience of urban society.

Another important reference for Mannix during the mid-1980s was the collection of Art Brut in Lausanne formed by the French artist Jean Dubuffet, which he first encountered in Roger Cardinal’s book Outsider Art (1972). The spiral motif that populates many of Mannix’s drawings in this period can be found in works in the Art Brut collection by Pascal-Désir Maisonneuve, whose sculptures incorporate spiral-shaped shells.29 One of the qualities of the spiral form is its capacity to confound the distinctions between what lies without and what lies within, thereby conveying a porosity between internal and external worlds, a fundamental principle of Mannix’s practice. Another artist from the Art Brut collection, Heinrich Anton Müller, who spent several years in mental hospitals in Switzerland in the early twentieth century and whose work was also reproduced in Cardinal’s book, was another important example for Mannix. Of particular interest to the artist were Müller’s drawings in which intrusions of space into the head, and extensions of the face into its surroundings, break down the borders between figure and background.30 The resulting effect is to demonstrate how the boundaries of beings, spaces, and things can be radically challenged at a visual level.

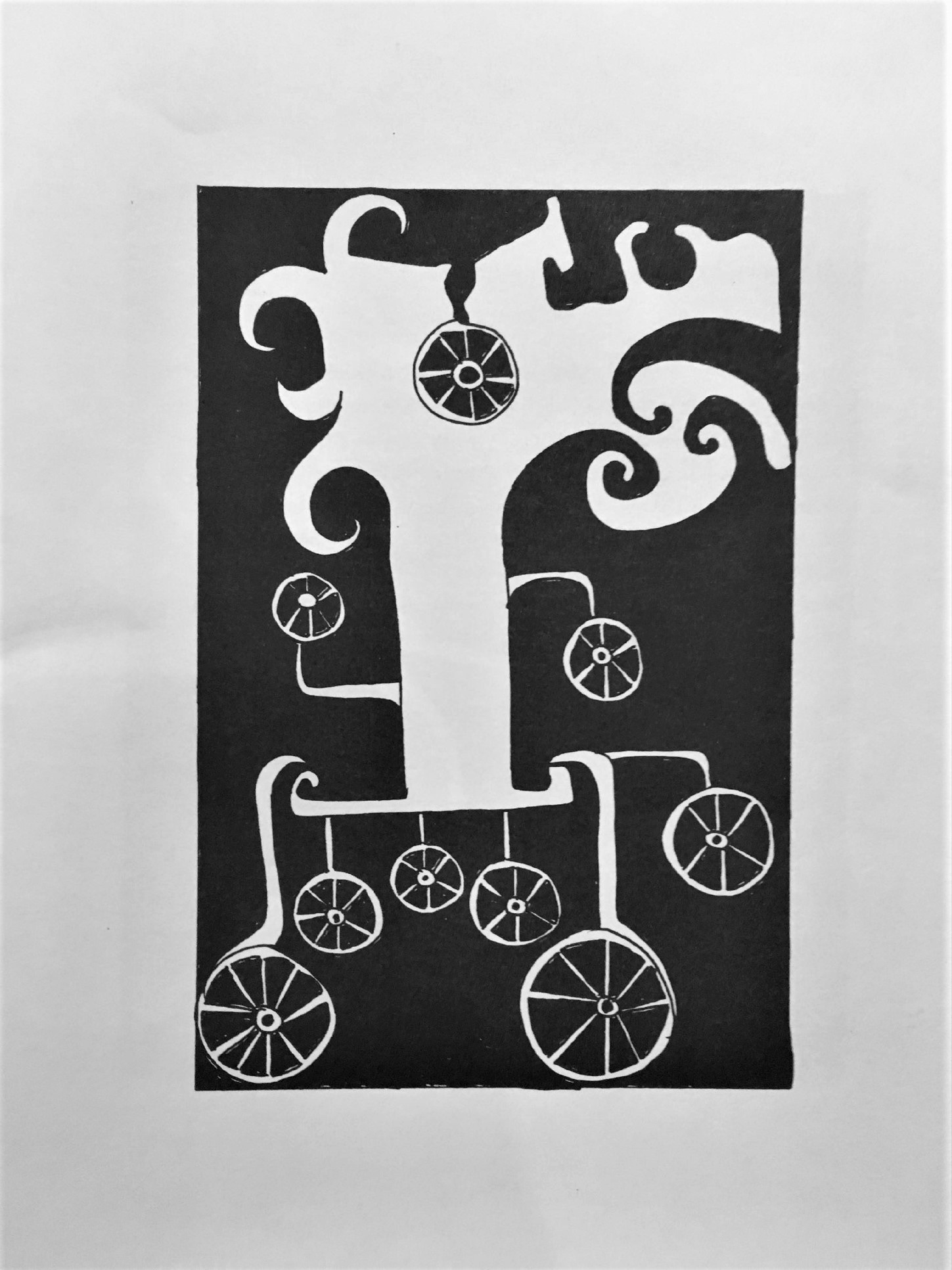

As Mannix explained, he was profoundly inspired by Cardinal’s book, where both Maisonneuve’s and Müller’s work appears, when he first read it in 1984, because “it was a very great revelation to see that other people made art on the same basis that I made it.”31 Mannix’s use of the spiral motif, and the radically anti-form quality drawn from Müller, convey the transformed sense of perception and reality that he attributes to psychotic experience. It is important to stress that by engaging with Müller, Mannix was not principally concerned to produce a meta-discourse or a reflexive citation of outsider art but to identify with the formal strategies he saw being employed in the work. The elaborate curlicues, for example, which invade the white-wheeled form which trundles across the page adjacent to Hammial’s text “The Vehicle of Reluctant Baptism” in Vehicles, draw our attention to the dark background as a prominent feature of the image (fig. 4). As a result, the white form becomes a negative space rather than a positive one. In this way our understanding of the identity of what features in the image becomes troubled, almost impossible to resolve.32 At the same time, Mannix was here also drawing his work into comparison with a known community of artists who were considered exceptions to the conventional art world.

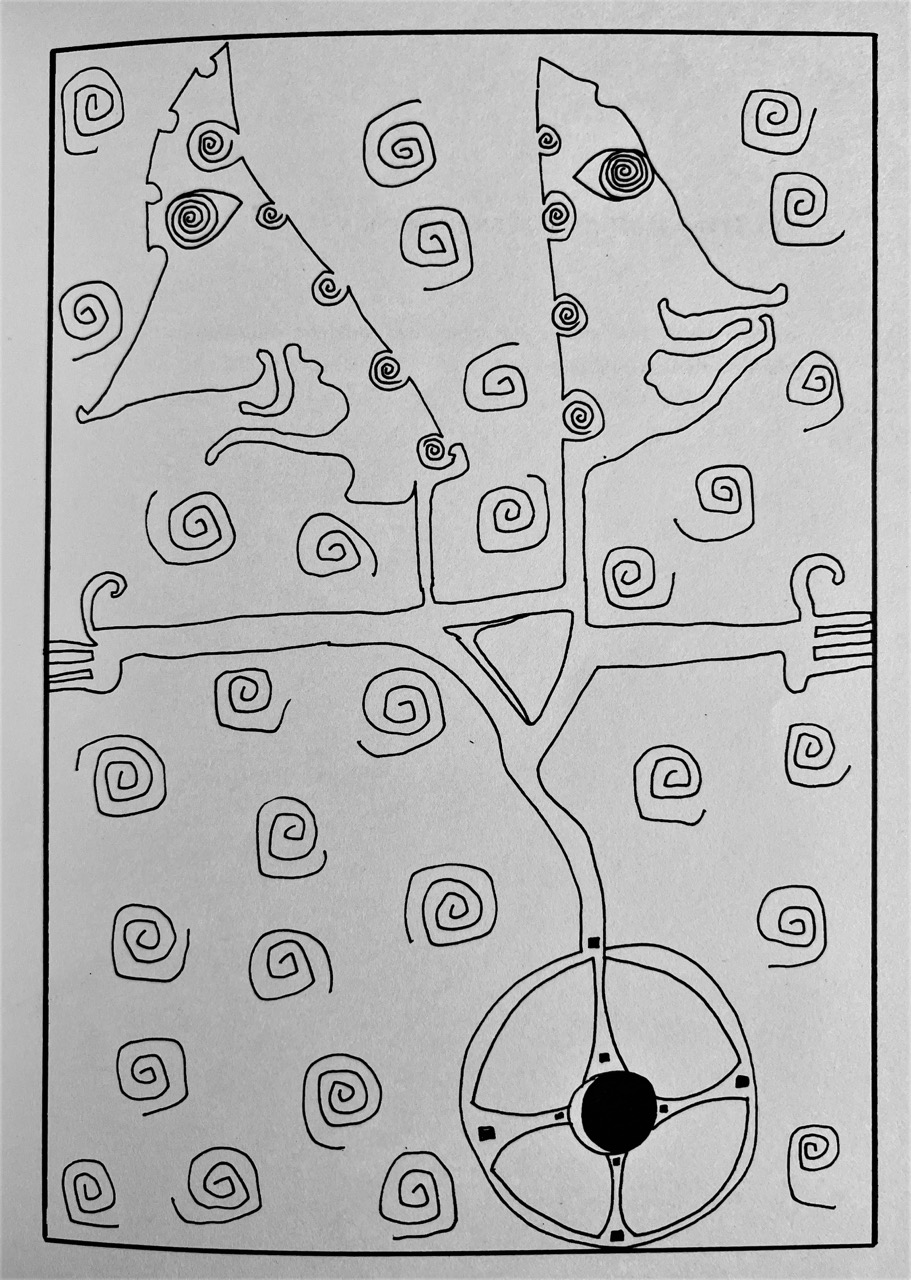

Beyond New Guinea art, and Art Brut, another tradition to which Mannix’s art bears comparison is the work of the Viennese Secessionist artist Gustav Klimt.33 An example is Mannix’s 1985 drawing for Vehicles which appears opposite Hammial’s text “The Vehicle of Subtle Idolatry,” featuring repeated spiral shapes evenly distributed across the background of a double-headed, wheeled figure (fig. 5). As in the repetition of similar spiral motifs in Klimt’s works, these drawings scatter attention across the surface to unite the image into an all-over array. They exemplify Mannix’s understanding of his own artistic practice as “exploring a landscape that is incongruent and has no sameness yet a oneness.”34 Again we find correspondences at a visual level with the “mixed realities” that Mannix has reported in his art and writing, the experience whereby boundaries between inside and outside, figure and space, imagined and real begin to break down.

Although Mannix has stated that he is not aware of being influenced either “consciously or unconsciously” by the work of the Viennese Secession, he recently noted that he momentarily believed he was “the reincarnation of Gustav Klimt.”35 Mannix may have been drawn to Klimt for his involvement in the Secessionist movement, an artists’ group that formally seceded from the established Artist’s Association in Vienna and critiqued the Vienna Academy of the Arts and the Vienna Kunstlerhaus. A particular focus of the Vienna Secession was to move away from the “economic way of thinking” prevalent within existing institutions and among professional artists. Rejecting the idea that “paintings are items of merchandise like trousers or cigars,” they encouraged artists to think of their work as “configurations of their innermost being.”36 Again, we find Mannix drawn to artists whose relationship to existing social and artistic structures was fraught rather than straightforward, evincing an idiosyncratic relationship to institutions such as the academy and the market. As these examples demonstrate, along with his engagement with both New Guinea art and Art Brut, access to the inside of Mannix’s reality takes place, at least in part, by virtue of access to the outside of the culture from which he emerged.

IV. Artist-Run Initiatives

While some of the drawings and prints from this period, as discussed above, were reproduced in publications like Vehicles, others by Mannix are in public and private art collections. Yet others are held by the artist himself, some of which have been incorporated into his many unique artist’s books. These latter works, including those titled Journal of a Madman, are now comprehensively documented on a website devoted to the artist’s work.37

These books are detailed records of a life dedicated to art over many years as Mannix experienced the mixed realities associated with his diverse mental states. Significantly, they also tell a history of the publication and exhibition of the artist’s works, as well as his involvement in several innovative art spaces that emerged in Sydney in the 1980s. These journals therefore produce a detailed history of Mannix’s career, including the artist’s involvement in alternative paradigms for the display of art.

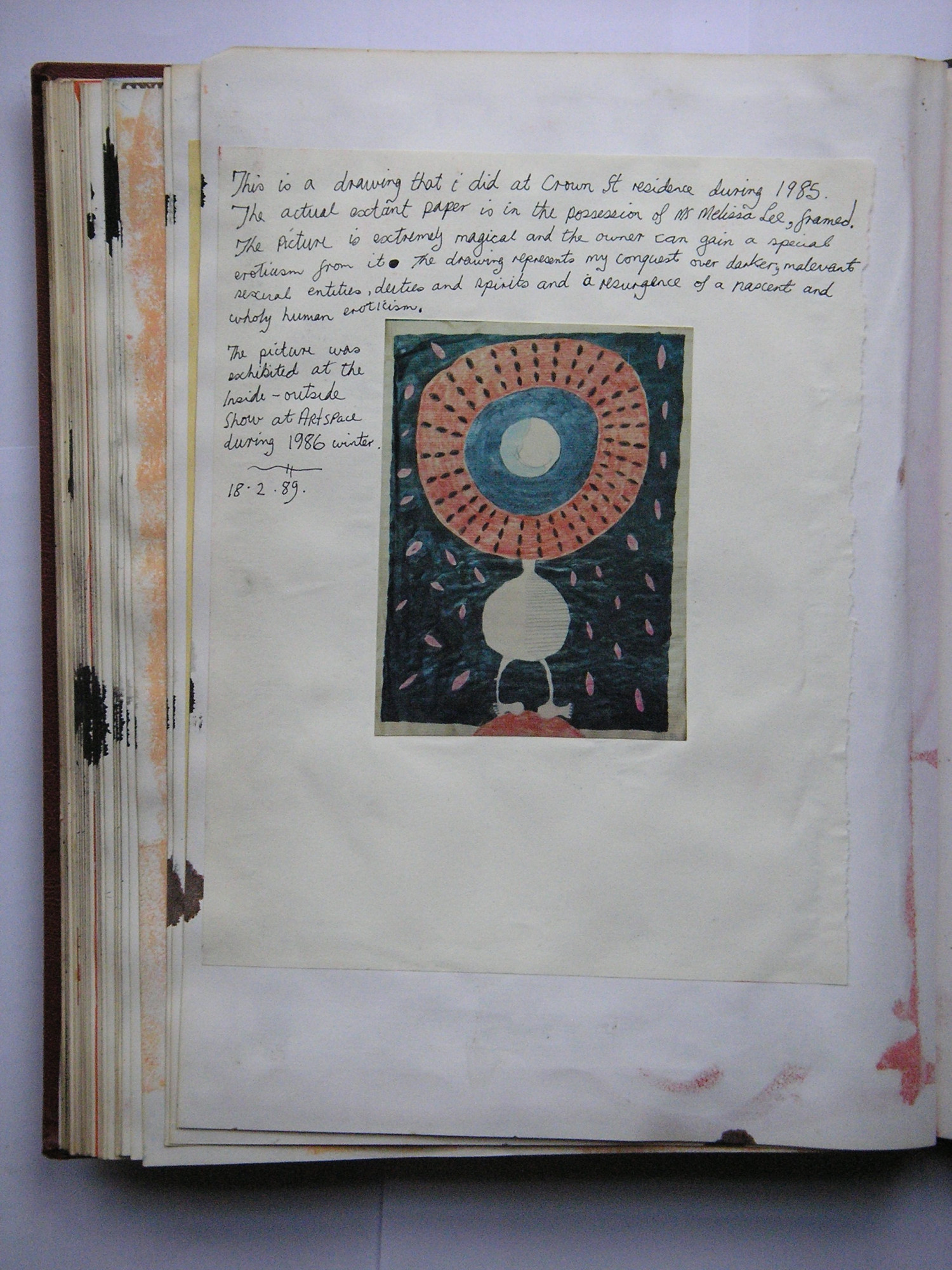

Pasted onto a page of Journal of a Madman No. 5 (1989) is a reproduction of a drawing that the artist completed in 1985 (fig. 6).38 It depicts a round-bodied being, with a disproportionately large head surrounded by dotted lines emanating from its centre on a red, corona-like background. The figure stands on a small mound before a field of black space which is interspersed with bright pink, leaf-like shapes cascading around it. As the artist comments in an inscription accompanying the image, “The drawing represents my conquest over darker, malevolent sexual entities deities and spirits and a resurgence of a nascent and wholly human eroticism.”39 From the text one gains insight into the meaning of the image, the realm of sexuality that led to its creation, and that for Mannix one of the functions of art was to explore aspects of his inner experience through aesthetic form. At the same time, a further note in the inscription gives details about the exhibition history of the image. As he notes: “The picture was exhibited at the Inside - outside show at Artspace during 1986 winter.” This information moves the work, and by extension the entire journal in which it appears, beyond the status of a document of a purely interior realm.

The venue Mannix refers to, Artspace, was founded in 1983 in Sydney, as a government funded, artist-run gallery. Set up specifically as an alternative to the existing system of commercial galleries and larger, state-run institutions, the organisation sought “to provide an alternative space for artists to meet, work and exhibit in, and to encourage and support less-established artists.”40 At the time of its founding, Artspace had a management structure involving a board elected from members, most of whom were practicing artists.41 The birth of this organisation in the 1980s is part of a long history of artist-run initiatives, which goes back several decades in Australia and includes other important Sydney spaces as Inhibodress, Central Street, and Firstdraft, but had one of its earliest manifestations in Gustave Courbet’s “Pavilion of Realism” at the 1855 Universal Exhibition in Paris.42 The exhibition at Artspace referred to in Mannix’s journal, held between May and June of 1986, was curated by Gary Sangster and titled Inside Out: An Exhibition of Outsider Art. Reviewed by Terence Maloon as an exhibition featuring the work of “self-taught artists with unusually powerful imaginations,” it included the work of practitioners with whom Mannix was connected socially and/or professionally, including Gunther Deix and Liz Parkinson.43 The exhibition was based on an idea by Terrence Relph who lent works for the show from the by-then defunct Outsider Gallery.44 Mannix’s journal serves as evidence, therefore, of the shift taking place in Sydney towards more alternative artistic spaces run on a cooperative model.

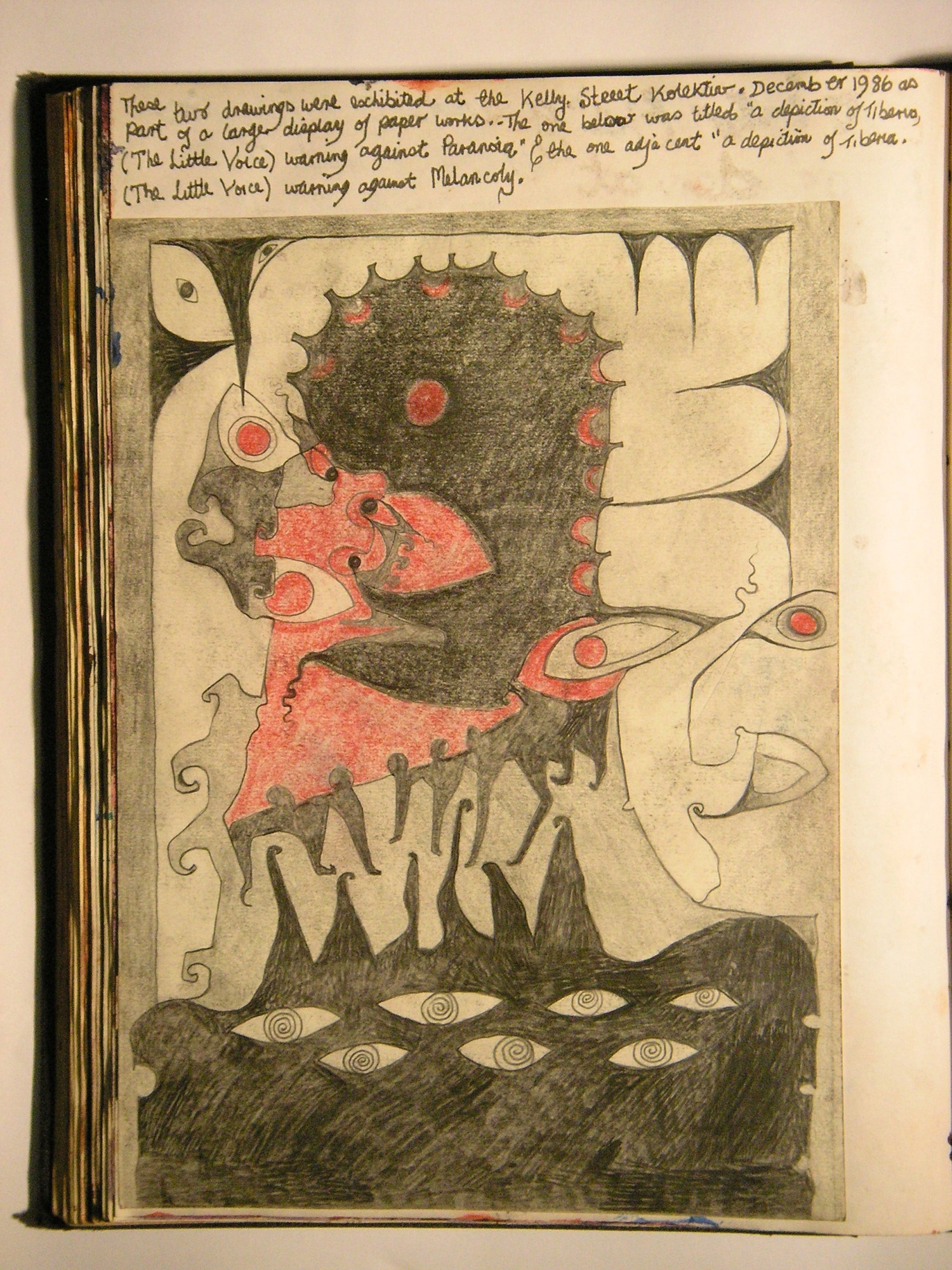

Another drawing Mannix produced in the mid-1980s, which the artist attached to a page of his Journal of a Madman No. 4 (1988–89), is titled A Depiction of Tiberia (The Little Voice) Warning against Paranoia (fig. 7).45 As the artist noted in a margin of the journal page, it was executed “in extreme conditions during late 1984. The degree of psychosis at the time was Acute. ‘Paranoia’ was drawn in the night without lighting in the woodlands between Glebe and Balmain while on the run from terrors.” The journal, through the addition of such texts explaining the circumstances of the work’s creation, supplies a context for understanding how the work related to the artist’s psychological experience and his difficult living conditions during that period.

When viewing the drawing in relationship to contemporary works, one can identify parallels with others produced by the artist in the mid-1980s, including those reproduced in Vehicles, with their decorative repetitions of form, curvaceous outlines, spiral shapes, and distorted faces. We also learn from the inscription that the work was exhibited in late 1986 at the Kelly Street Kolektiv, an artist-run gallery in Sydney. This journal page, like others within Mannix’s series of artist’s books documenting various aspects of his involvement with Kelly Street Kolektiv—including a page in Rupture (1999) to which the artist attached a proof sheet of photographs documenting the installation of the 1986 exhibition—further demonstrates how the artist’s life and work intersected with the alternative art world in Sydney at the time.46

Located in the upper level of an industrial building in Sydney, the Kelly Street Kolektiv, of which Mannix was a founding member, had as its goal the “promotion of practitioners independently of the mainstream art structures.”47 Its “inclusive and democratic” management structure required members to take on several different roles in the organisation, including finance, and curatorship, along with other tasks like cleaning and lighting.48 Membership was open, based on capacity to pay, to “anyone who calls themselves an artist,” and exhibitions were offered to all, organised on a roster system.49 As Mannix has recently recalled, it was an organisation of “artists by themselves, for themselves.”50 Although there was no stated curatorial policy for the shows mounted at the organisation, and selection was based upon agreement to participate in the organisation’s “internal democratic processes,” the Kolektiv was unwavering in its determination “to provide support and a public for art workers who might otherwise remain isolated.”51 Among the shows which took place there were exhibitions of work by Mikala Dwyer; group exhibitions dedicated to the practice of women artists; a noteworthy effort to “arrange exhibitions for, and foster interest in, Sydney Art Brut”; and displays of art by former inmates of the New South Wales prison system.52 In addition, some of its members, including Mannix, held exhibitions in collaboration with the Breakout Printing Cooperative run by the Prisoners’ Action Group in Pitt Street, Sydney.53

Mannix’s involvement in this “counter establishment” organisation, which withdrew from the established art system to set up alternative structures for the exposure and promotion of art—and for which “government support was rejected”—brought him into contact with others who sought to give their art a platform away from the mainstream art system.54 In other words, as the artist’s journals demonstrate, active engagement in these communities of secession have been important for the artist’s work, through organisations that, while forming “an integral part of Sydney’s art network” and working to foster a sense of community and accessibility, also insisted on forms of radical autonomy conducive to idiosyncratic artistic experimentation.55 This shows that while Mannix was keyed into an aspect of the broader contemporary art world in Sydney, he was also helping to establish a new dimension of that world palpably at odds with, and involved in a process of rebellion against the dominant currents in Sydney art of the time.

V. Hospitals

An important dimension of Mannix’s practice, as Gareth Jenkins has noted, has involved the artist reflecting upon his experience of diverse mental health “from the perspective of one well informed regarding the culturally dominant constructions of madness.”56 This is evident in his journals, unique artist’s books into which the artist pastes drawings and other items as a record of his life and work. Although these works do give significant insight into the experience of psychosis, they also speak directly to Mannix’s experience of institutionalisation. Even as he underwent sometimes involuntary incarcerations in psychiatric hospitals, the record of Mannix’s art shows that he also seceded, literally and figuratively, from that institution, its discourses, and its prerogatives. Moreover, Mannix’s Journals are a sustained critique of the very principle of the asylum: in particular, its language of “illness” to describe the nature of his experiences. As the artist has explained, he is opposed to “the labelling of pursuing other realities and altered states simply as illness” and has worked as “a silent activist” on behalf of those who “just don’t fit the norm at the moment.”57 Mannix institutes a radical positivity that refuses the discriminatory principle at work in the language of illness and within the mental health system more broadly.

Rozelle Psychiatric Hospital and Gladesville Hospital, mental health institutions in New South Wales to which Mannix has been confined, were established in the nineteenth century. As Vaughan Carr has argued, the founders of these organisations designed the asylum as a dedicated facility “which promoted seclusion from suspected causes of illness in natural environments with extensive grounds and cultivated parks, away from pollutants and urban centres, with the intention of curing mental illnesses.”58 In this sense, the institutions were conceived—similarly to others in Europe and the United Kingdom—as retreats from those pressures of modern life which were, it was felt, the trigger for illness. According to Leonard Smith, the view was that “By receiving treatment in the sequestered asylum, the sufferer could be insulated from that cause and placed back on the road to recovery.”59 The reality, however, of such institutions by the time Mannix encountered them, if not from their very inception, diverged markedly from these ideals.

As submissions to The National Inquiry into the Human Rights of People with Mental Illness documented in 1991–92, individuals subject to the mental health system in Australia regularly experienced discrimination, abuse, inappropriate medication, and other forms of ill-treatment.60 Such reports were one of many factors leading to the process of deinstitutionalisation which took place at the end of the twentieth-century, which saw treatment move from stand-alone hospitals to a community service model.61 As his journals document, Mannix’s experience of the institutions was commensurate with that recorded in these reports, and as his journals demonstrate, his fundamental antagonism to the hospital system compelled him to seek ways to withdraw from or rebel against its strictures.

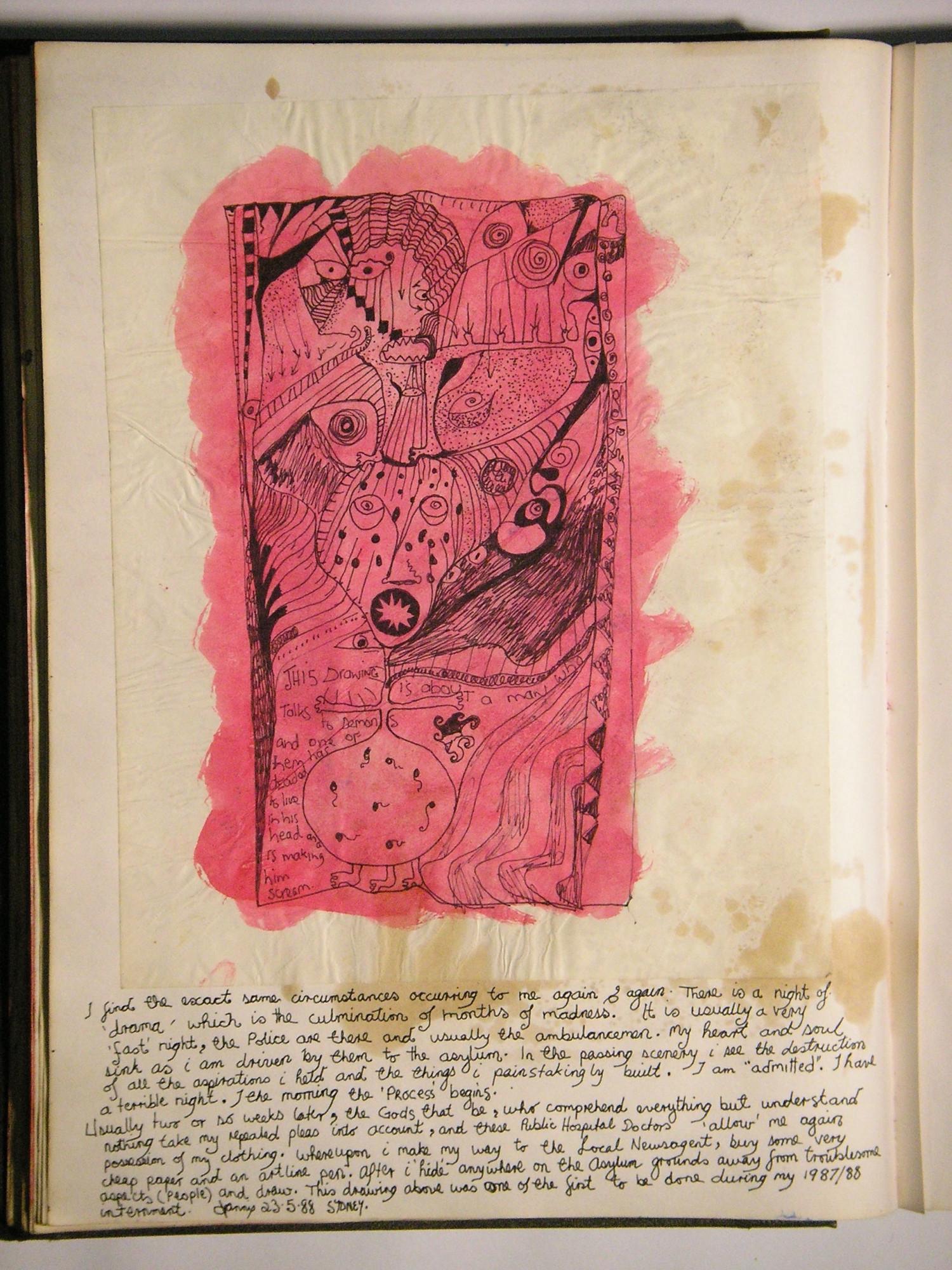

A page from Journal of a Madman No. 4 (1988) presents a highly detailed drawing produced during the artist’s internment during late 1987, and early 1988, in Rozelle Psychiatric Hospital (fig. 8).62 It shows a figure surrounded by intensely drawn decorative patterning, with tadpole-like beings swirling over its stomach, and a second personage who is standing on the first figure’s head. The image is reminiscent of some of the artist’s earlier drawings and images, with its zigzag shapes relating to New Guinea printmaking, high-contrast, segmented fields of light and dark colour, all-over compositional layout, and concentric circles and distorted anatomy in response to artists whose work had been published as “outsider art.” As Mannix notes in a text incorporated into the image, “this drawing is about a man who talks to demons and one of them has decided to live in his head and is making him scream,” thereby conveying the experience whereby the distinction between what is real and what is imagined breaks down.

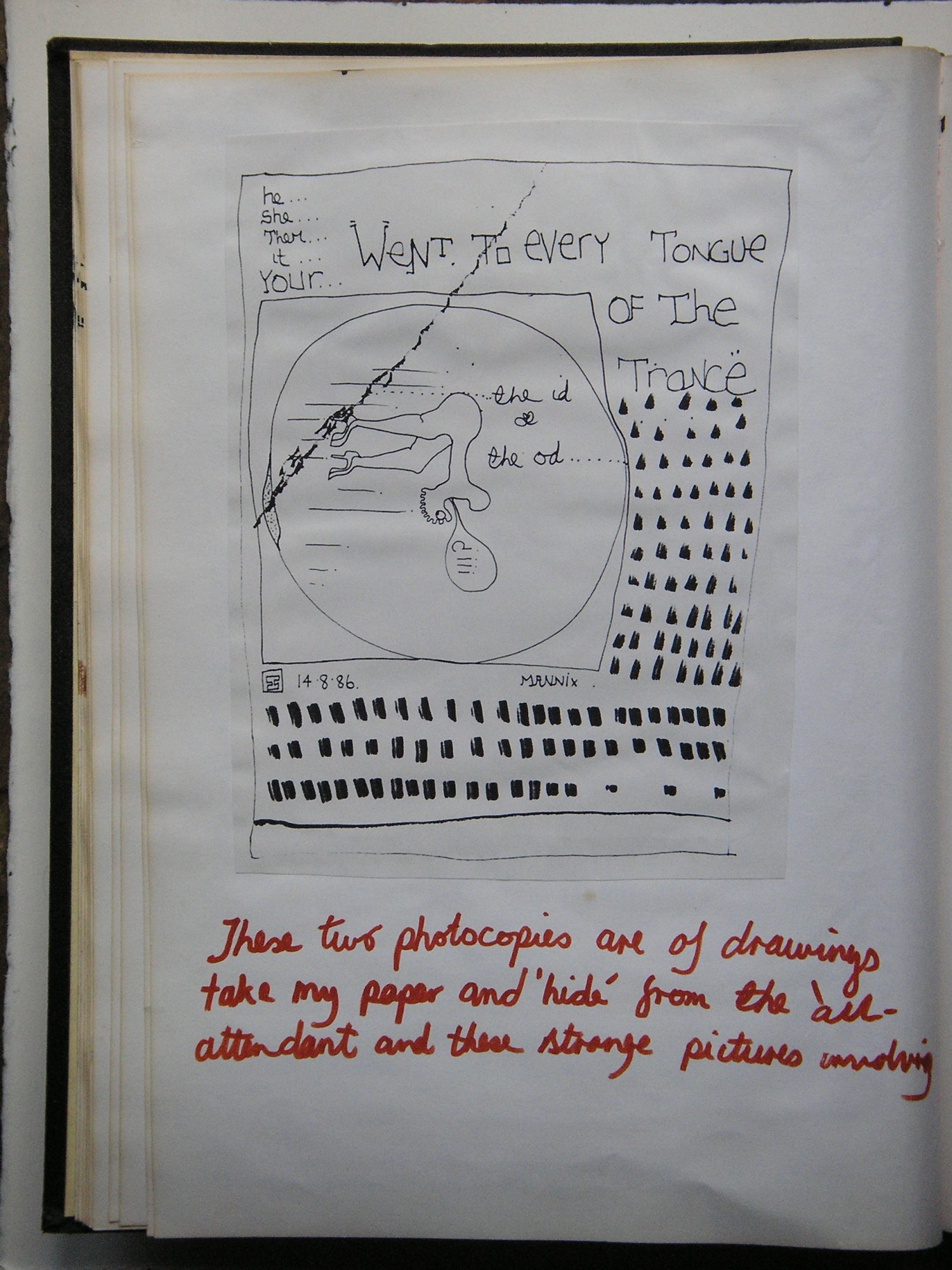

A text by the artist appended to the drawing provides further context for the image, describing the traumatic “process” of being interned in the psychiatric hospital, a procedure subject to severe criticism in the National Inquiry of 1991–92. Mannix’s text also explains how the artist, while still hospitalised, made short trips outside of the asylum, during which “I make my way to the Local Newsagent, buy some very cheap paper and an artline pen. After i ‘hide’ anywhere on the Asylum grounds away from troublesome aspects (People) and draw.” Similarly, in Journal of a Madman No. 6 (1989), an inscription by the artist accompanying copies of drawings he executed in August 1986 while at Rozelle, notes he would take his drawing materials and remove himself to a part of the institution away from the ‘all seeing’ eye of the hospital and its attendant” and produce “these strange pictures involving the figure and the power of the word” (fig. 9).63 The images, which show distorted figures with bizarre anatomy, surrounded by linguistic jokes playing on sound and meaning, and embellished with decorative stippling, were part of a deliberate strategy of withdrawal from the system of the hospital and its surveillance mechanisms.

This aspect of his relationship to institutions would intensify in subsequent years, as recorded in Journal of a Madman: Erogeny (1995), which the artist describes as “a documentation of the unconscious psychosis… ‘in situ’ on the grounds of Rozelle Mental asylum.”64 Finding himself once more, during 1995, in a “tightly run, closely administered institution,” he writes: “I walked out of the ward I was in at Rozelle Hospital extremely dissatisfied. I wanted more. Shortly after I occupied a building that resembled a house on the grounds. None knew I was there. Here in this derelict building I set up my art factory.”65 In this building, Mannix began creating art works, using a range of found materials including “biros, felt Pens, types of paper and office station[e]ry” while returning to his ward from time to time for meals and medication.66 The works he created there, through which, as Jenkins has argued, Mannix set out to “construct an alternate world within which to exist,” include ruminations on sexuality, psychosis, and the hospital, as well as fantasies about letters he discovered on the grounds of the institution.67 His experiences during this time are documented in a series of dazzling and confounding images and texts that aim to record the processes of the unconscious, woven together retrospectively into an artist’s book. In the process, the artist explains, in his self-constructed “drawing factory” he was able to elude the hospital’s controlling mechanisms and his “captors the psychological wards” to the extent that he was able to “cease being a captive.”68

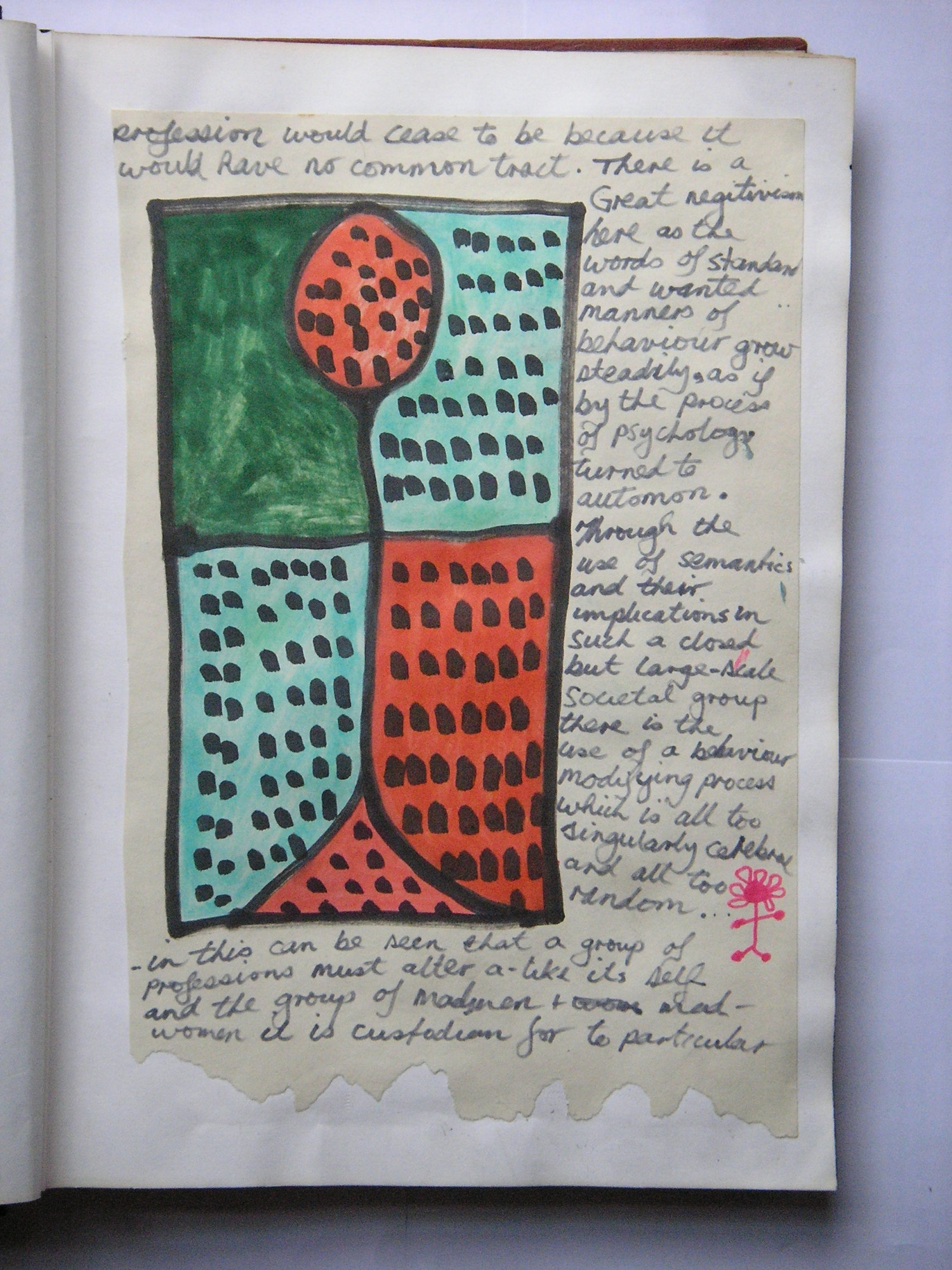

Journal of a Madman No. 5 (1989) includes a series of drawings pasted into the book which document the artist’s experience of Gladesville Hospital (fig. 10).69 As the artist explains, these drawings, “The Journal of the Luminous Man,” constitute “eight pages of illustrations, graphics, and critique.”70 The “luminous man” is one deemed “psychotic” within the medical system. Using crudely drawn, stick-figure like personages, highlighted with brightly coloured ink—thereby addressing the artificial sense of singularity and isolation of the hospitalised individual within the highly structured and discursively constrained space of the medical institution—Mannix conveys the intense alienation that the interned individual experiences within the hospital setting. He also documents how that system self-interestedly perpetuates itself by nourishing the careers of the professionals who work there, while neglecting the individuals who are subject to the institution’s procedures.71 In creating these works, Mannix engages with the tradition of anti-psychiatry and the critique of asylums that emerged internationally in the 1960s in the work of writers such as R. D. Laing.72 The highly saturated hues of the drawn figures accompanying the text, created by the intensity and massing of coloured ink around their bodies, highlights the perceived anomalous quality of the interned person within the mechanism of the hospital, while also referring to the psychic and institutional energy of which that individual becomes the focus.

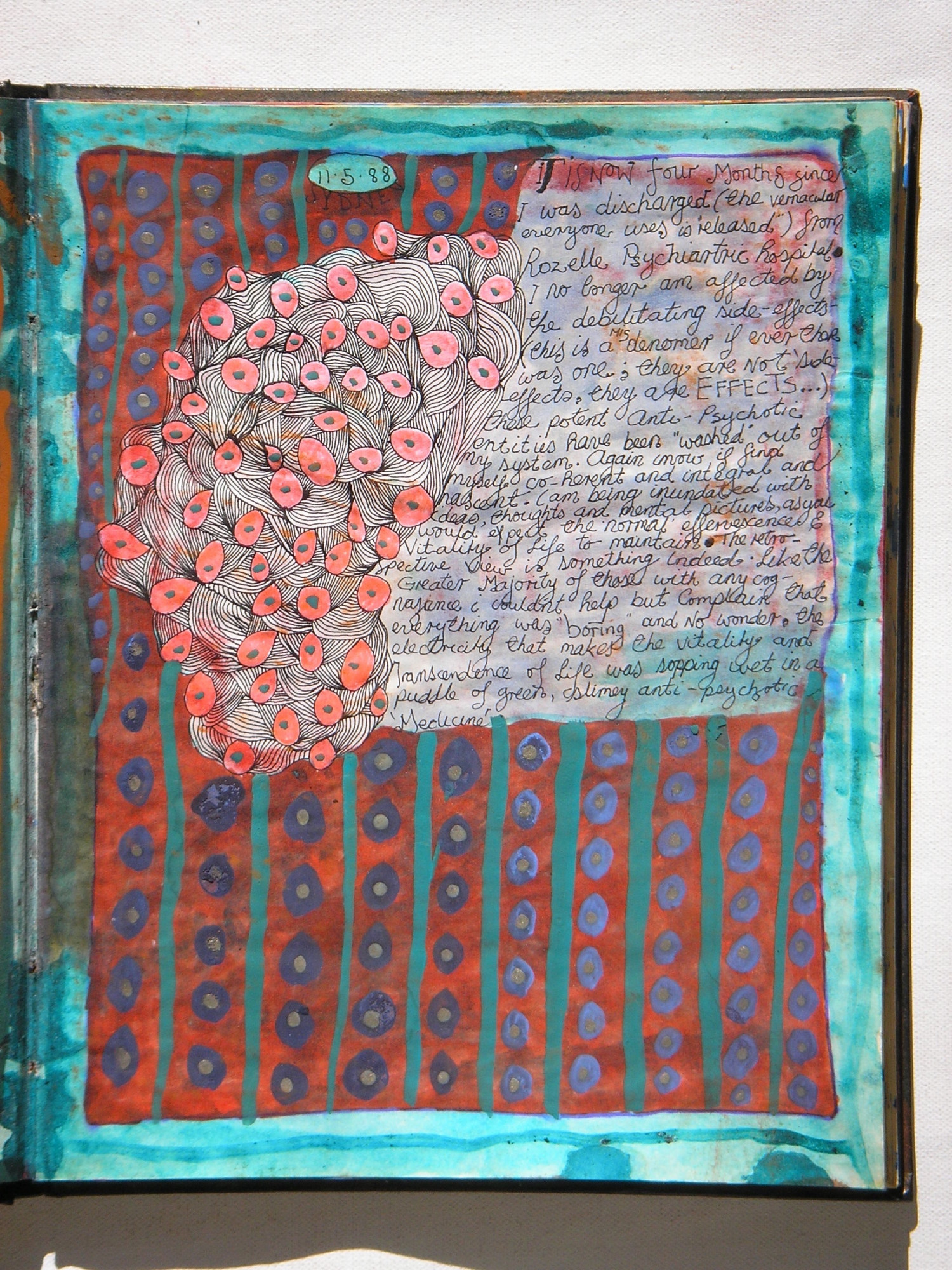

Another work, applied to a page in Journal of a Madman: Notes on Dementia (1988), shows an amorphous form composed of segments of closely drawn, high-contrast lines of black ink, again displaying correspondences with the detailed, black-and-white arrays of geometric form encountered in 1970s New Guinea printmaking (fig. 11).73 The form, covered in orange circles with blue dots giving the appearance of dozens of eyes, floats before a pattern of stripes and ovals composed of starkly-opposed hues of green, orange, and purple, evoking the intense, dazzling fields of colour encountered in Secessionist graphic design. An inscription which Mannix has incorporated into the image describes the artist’s experience after being released from Rozelle Psychiatric Hospital once the effects of antipsychotic medication have worn off. Whereas earlier, while he was being treated, “the electricity that makes the vitality and transcendence of life was sopping wet in a puddle of green, slimy, antipsychotic ‘Medicine.’” By contrast, once he has withdrawn from the drugs and their effects have subsided, as the artist explains “I find myself coherent and integral and nascent. I am being inundated with ideas, thoughts and mental pictures, as you would expect the normal effervescence & vitality of life to maintain.” The image is a vivid testament to the changing experience of the artist as he emerges from his confinement and the effects of powerful medication, and into his characteristic mental state. It draws upon artistic influences from a wide variety of cultural sources to give access to the experience of psychosis and the changing circumstances of the artist as he withdraws both figuratively and literally from the institution where his art and existence were severely constrained.

VI. The Beast

In his work, Mannix has performed a wilful secession from established conventions, institutions, and networks. This has been part of the artist’s lifelong effort to build an alternative structure and practice to give voice to his experience. The problem with the language of “outsider art” within which Mannix’s work has conventionally been framed is that it does not acknowledge this conscious activity of breaking away from the settled organisations and conceptions that have impinged upon his life and work. For this reason, Mannix may be fruitfully compared to other modern and contemporary artists for whom, as Martin Herbert has argued of artists who withdraw from the art world, “absenting has served, variously, as a reservoir of energy and a permission for idiosyncrasy and… inner journeying.”74 This breaking away within Mannix’s work, and its association with other like-minded forms of artistic secession, is perhaps nowhere more evident than in his aforementioned artist’s book Rupture (1999).75

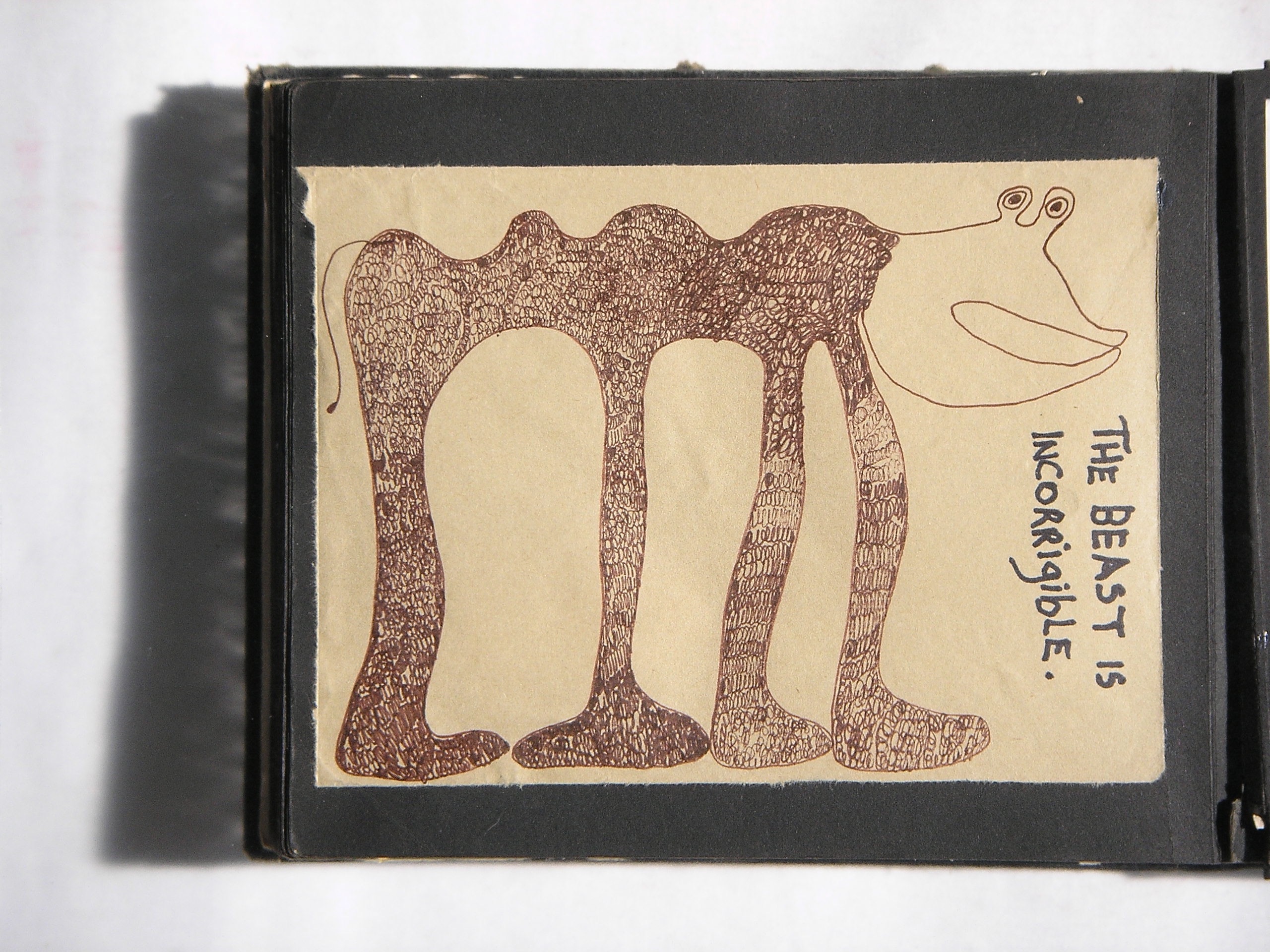

Upon the pages of this work, which repurposes a found, empty photo album, Mannix attached several of his own drawings along with those of his artistic fellow-travellers Philip Heckenberg and Janine Hilder. Bringing together these works with his own, Mannix gathers images and texts which together operate a kind of secession from mainstream institutions of art. The artist also attached type-written sheets to pages of the book, where he notes that, “I have ceased to talk about mental asylums… In surviving them I maintain that I have conquered them.” He subsequently adds that “nothing is absent, all is filled… there are no such existences as borders, definitions, limits.”76 These ideas are fulfilled textually and visually later in the book in a series of drawings portraying “The Beast,” a creature the artist elsewhere nominates “The Beast of the Unconscious” and which represents “the shift from one place of the psychotic payload to another.”77 Alongside these drawings, all of which show a multi-legged being whose grimacing face and amorphous limbs sprawl into every corner of the page, Mannix has inscribed a number of texts describing the animal. Among the beast’s qualities are that he “knows every space”; “has a foot in everything”; “is incorrigible”; and “knows no negatives” (fig. 12).78 Seceding from the compulsion to exclude, select, and discriminate, which is endemic to institutions of art and mental health, Mannix opts for a radical form of idiosyncrasy which withdraws from limits by abandoning the concept of limit itself.

-

Anthony Mannix, personal communication, January 2, 2021. “Lived experience” refers to firsthand knowledge. See https://www.health.vic.gov.au/mental-health-reform/lived-experience, accessed August 24, 2022. “Diverse mental health” is used here to describe the full range of lived experience beyond any particular diagnosis or diagnoses. See Heidi Everett, author, and mental health advocate, http://www.heidieverett.com.au/learn.html, accessed August 24, 2022. ↩

-

“Studio 79”, Sydney Morning Herald, August 15, 1981, 51, Advertisement; Outsider Art (Sydney: The Outsider Gallery, 1982), Exhibition Catalogue, n.p. ↩

-

Outsider Art, n.p. ↩

-

Roger Cardinal, Outsider Art (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1972). ↩

-

Herbert Eckert, “Liz Parkinson: Images of Australian Hermit Art,” Aspect 21 (June 1981): 64–68, 65. ↩

-

David Maclagan, “The Madness of Art and The Art of Madness,” Raw Vision 27 (Summer 1999): 20–27. ↩

-

Georgina Beier, “Outsider Art in the Third World,” Aspect: Art and Literature 3, 1/2 (1978): 30–38. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, quoted in Anne Loxley, “Emotional Intelligence and the Confusions of the Psyche,” in Anthony Mannix: The Beast of the Unconscious and Other Well-Known Entities (Penrith: Penrith Regional Gallery, 2009), Exhibition Catalogue, 24. ↩

-

Ulli Beier, “Outsider Art: An Introduction,” Aspect 35 (1989): 7–14, 11. ↩

-

Refusing Any Annexation, February 5–March 28, 1992, Wollongong City Gallery, Wollongong. ↩

-

Mannix’s thinking in this regard bears comparison with the conception of “difference” in the work of Gilles Deleuze: “difference is affirmation: This proposition, however, means many things: that difference is an object of affirmation; that affirmation itself is multiple; that it is creation but also that it must be created, as affirming difference, as being difference in itself. It is not the negative which is the motor.” Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition (1968; repr. London: Bloomsbury, 2004), 67. ↩

-

“Anthony Mannix’s Story,” Mental Health Commission of New South Wales, 2014, accessed April 7, 2022, https://www.nswmentalhealthcommission.com.au/journey/anthony-mannixs-story. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, Outsider Art Statement (undated, n.p.). This and subsequent references to unpublished works by Mannix can be found at a website maintained by Gareth Jenkins, The Atomic Book, https://www.theatomicbook.com/the-book. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, Journal of a Madman, 1994–95, unique artist book, private collection, 142. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, “The Demise,” in Anthony Mannix, The Toy of the Spirit (Waratah: Puncher and Wattman, 2019), 110. ↩

-

Gareth Jenkins, “Art of Being, Being of Art,” in Anthony Mannix, The Toy of the Spirit (Waratah: Puncher and Wattman, 2019), 22. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, Journal of a Madman, 1995, unique artist book, private collection, 158 ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, Journal of a Madman, 1996 and 2002, journals, unique artist book, private collection, 19. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, Journal of a Madman No. 5, 1989, unique artist book, private collection, 70. ↩

-

Philip Hammial, “The Australian Collection of Outsider Art,” in Australian Outsiders (Orange: Orange Regional Gallery, 2006), Exhibition Catalogue, n.p. See also Philip Hammial,” The Australian Collection of Outsider Art,” Artlink 12, no. 4 (1992–93): 19. ↩

-

Philip Hammial with Anthony Mannix, Vehicles (Sydney: Island Press, 1985). ↩

-

Beier, “Outsider Art in the Third World,” 30–38. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, “Anthony Mannix Talks to Ulli Beier,” Aspect 35 (1989): 69. ↩

-

Philip Hammial with Anthony Mannix, Vehicles, n.p. ↩

-

Beier, “Outsider Art in the Third World,” 36, 35. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, The Chasm, 1994–95, unique artist book, private collection, 98. ↩

-

Beier, “Outsider Art in the Third World,” 31. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, Journal of a Madman No. 6, 1989, unique artist book, private collection, 47. ↩

-

Cardinal, Outsider Art, 72–73. See also Mannix, “Anthony Mannix talks to Ulli Beier,” 75. ↩

-

Cardinal, Outsider Art, 31. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, “Outsider Art,” All in the Mind, interview by Lynne Malcolm, Australian Broadcasting Commission, March 11, 2006, audio, 30:00, https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/allinthemind/outsider-art/3305568?searchTerm=subject%3A+%22Outsider+art%22#transcript. ↩

-

Hammial with Mannix, Vehicles, n.p. ↩

-

See, for example, Gustav Klimt, Design for the Stoclet Frieze: Figural Composition “Die Erfüllung” or “Unmarmung,” 1908–10, reproduced in Vienna 1900 and the Heroes of Modernism, ed. Christian Brandstätter (London: Thames & Hudson, 2005), 100. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, The Chasm, 1994–95, unique artist book, private collection, 161. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, personal communication, May 2, 2022. ↩

-

See Hermann Bahr, “Our Secession,” Die Zeit 11, no. 139 (May 29, 1897), reprinted in Art in Theory, 1815–1900, ed. Charles Harrison, Paul Wood, and Jason Gaiger (Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), 914–16. ↩

-

“The Atomic Book,” accessed April 9, 2022, https://www.theatomicbook.com/the-book. ↩

-

Mannix, Journal of a Madman No. 5, 94. ↩

-

Mannix, Journal of a Madman No. 5. ↩

-

Susanna Short, “Artspace has Room for a New View,” The Sydney Morning Herald, February 18, 1983, 12. See also “About Us,” Artspace, accessed April 9. 2022, https://www.artspace.org.au/about/about-artspace/. ↩

-

Susanna Short, “Artspace has Room for a New View,” The Sydney Morning Herald, February 18, 1983, 12. ↩

-

Jacqueline Milner, “We Are… Have Been… Here: A Brief, Selective Look at the History of Sydney ARIs,” in National Association of Visual Arts and Firstdraft, We Are Here, ed. Brianna Munting and Georgie Meagher (Sydney: NAVA, 2011), 62–65. ↩

-

Terence Maloon, “Essences for the Living Dead,” The Sydney Morning Herald, June 6, 1983, 18; “Artspace” The Sydney Morning Herald, June 13, 1986, 52. ↩

-

“A Brief History of the Mostly Fruitless Attempts to Bring Outsider Art to the Public’s Attention in Australia,” Art & Text 27 (1988): 63; “Artspace.” ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, Journal of a Madman No. 4, 1988–89, unique artist book, private collection, 77. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, Rupture, 1999, journal, unique artist book, private collection, 50. ↩

-

Anna Couani, “‘Beauty Is Now Underfoot Wherever We Take the Trouble to Look,’” Sydney Review of Books, November 17, 2017, accessed April 9, 2022, https://sydneyreviewofbooks.com/essay/new-essay-anna-couani-glebe/. ↩

-

Anna Couani, “Interview with Australian Writer Anna Couani”, The Centre for Race Autobiography Gender and Age Studies, The University of British Columbia, January 18, 2005, accessed April 9, 2022,

http://www.raga.ubc.ca/downloads/Public_intellectuals/Couani_interview_public%20intellectuals.pdf; Louisa Costa, “Young Artists at Work,” The Sydney Morning Herald, February 12, 1987, 41. ↩

-

Anna Couani, “‘Beauty Is Now Underfoot”; Anne McDonald, “Alternative Spaces Sydney,” Art and Australia 26, no. 1 (Spring 1988): 46–47. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, personal communication, March 14, 2022. ↩

-

McDonald, “Alternative Spaces Sydney,” 47. ↩

-

McDonald, “Alternative Spaces Sydney,” 46–47, 47; ““Kelly Street Kolektiv” The Sydney Morning Herald, Metro, April 25, 1988, 10; Anne Loxley, “Woman as Goddess,” The Sydney Morning Herald, July 24, 1988, 93. ↩

-

Philip Hammial, “Outsiders Down Under,” Raw Vision 8 (Winter 1993–94): 34–37, 37. ↩

-

Loxley, “Woman as Goddess,” 92; Anthony Mannix, personal communication, March 14, 2022. ↩

-

McDonald, “Alternative Spaces Sydney,” 46–47; 47. ↩

-

Gareth Jenkins, “Anthony Mannix: ‘The Atomic Book’,” (Ph.D., University of Wollongong, 2008), 261. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, personal communication, April 19, 2019. ↩

-

Vaughan Carr, “Mental Health,” in Callan Park Master Plan Report (McGregor Coxall Landscape Architecture and Urban Design, 2011), 48–52, 48. ↩

-

Leonard Smith, “Cure, Comfort and Safe Custody”: Public Lunatic Asylums in Early Nineteenth-Century England (London: Leicester University Press, 1999), 112. Quoted in Leslie Topp, “Otto Wagner and the Steinhof Psychiatric Hospital,” The Art Bulletin 87, no. 1 (March 2005): 130–156, 137. ↩

-

Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, Human Rights & Mental Illness: Report of the National Inquiry into the Human Rights of People with Mental Illness (Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1993). ↩

-

Janice Chesters, “Deinstitutionalisation: An Unrealised Desire,” Health Sociology Review 14 (2005): 272–282. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, Journal of a Madman No. 4, 1988, unique artist book, private collection, 40. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, Journal of a Madman No. 6, 1989, journal, unique artist book, private collection, 24–25. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, Journal of a Madman: Erogeny, 1995, unique artist book, private collection, 1. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, Journal of a Madman: Erogeny, 2. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, Journal of a Madman: Erogeny, 3. ↩

-

Jenkins, “Anthony Mannix: ‘The Atomic Book,’” 158. ↩

-

Mannix, Journal of a Madman: Erogeny, 1. ↩

-

Mannix, Journal of a Madman No. 5, 8, 16. ↩

-

Mannix, Journal of a Madman No. 5, 8. ↩

-

Mannix, Journal of a Madman No. 5, 8–16. ↩

-

Belinda Robson, Recovering Art: A History of the Cunningham Dax Collection (Parkville: The Cunningham Dax Collection, 2006), 22; Janice Chesters, “Deinstitutionalisation: An Unrealised Desire,” Health Sociology Review 14 (2005): 272–282, 275–76. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, Journal of a Madman: Notes on Dementia, 1988, unique artist book, private collection, 7. ↩

-

Martin Herbert, Tell Them I Said No (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2016), 12. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, Rupture, 1999, unique artist book, private collection. ↩

-

Mannix, Rupture, 1999. ↩

-

Anthony Mannix, quoted in Anne Loxley, “Emotional Intelligence and the Confusions of the Psyche,” in Anthony Mannix: The Beast of the Unconscious and Other Well-Known Entities (Penrith: Penrith Regional Gallery, 2009), Exhibition Catalogue, 24–25, 25. ↩

-

Mannix, Rupture, 45, 47–49. ↩

Anthony White’s research focuses on the history of modern and contemporary art. His forthcoming co-authored book, Recentring Australian Art (2023), investigates artists who have been excluded from mainstream art history. He is the author of Italian Modern Art in the Age of Fascism (2020); Art as Enterprise: Social and Economic Engagement in Contemporary Art (with Grace McQuilten, 2016); and Lucio Fontana: Between Utopia and Kitsch (2011). He has written for Grey Room, October, Third Text, and Artforum. He curated the exhibitions Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles (National Gallery of Australia, 2002) and The Art of Making Sense (The Dax Centre, 2008).

Bibliography

- “A Brief History of the Mostly Fruitless Attempts to Bring Outsider Art to the Public’s Attention in Australia.” Art & Text 27 (1988): 63.

- “Anthony Mannix’s Story.” Mental Health Commission of New South Wales, 2014. https://www.nswmentalhealthcommission.com.au/journey/anthony-mannixs-story.

- “Artspace.” The Sydney Morning Herald, 13 June, 1986, 52.

- Bahr, Hermann. “Our Secession.” Die Zeit 11, no. 139 (29 May, 1897). Reprinted in Art in Theory, 1815-1900. Edited by Charles Harrison, Paul Wood, and Jason Gaiger. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2003, 914-16.

- Brandstätter, Christian (ed.). Vienna 1900 and the Heroes of Modernism. London: Thames & Hudson, 2005.

- Cardinal, Roger. Outsider Art. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1972.

- Carr, Vaughan. “Mental Health.” In Callan Park Master Plan Report. Melbourne: McGregor Coxall Landscape Architecture and Urban Design, 2011.

- Costa, Louisa. “Young Artists at Work.” The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 February, 1987, 41.

- Couani, Anna. “Interview with Australian Writer Anna Couani.” The Centre for Race Autobiography Gender and Age Studies, The University of British Columbia, 18 January, 2005,http://www.raga.ubc.ca/downloads/Public_intellectuals/Couani_interview_public%20intellectuals.pdf.

- Couani, Anna. “‘Beauty Is Now Underfoot Wherever We Take the Trouble to Look.’” Sydney Review of Books, 17 November, 2017. https://sydneyreviewofbooks.com/essay/new-essay-anna-couani-glebe/.

- Beier, Georgina. “Outsider Art in the Third World.” Aspect: Art and Literature 3, 1/2 (1978): 30-38.

- Beier, Ulli. “Outsider Art: An Introduction.” Aspect 35 (1989): 7-14.

- Chesters, Janice. “Deinstitutionalisation: An Unrealised Desire.” Health Sociology Review 14 (2005): 272-282.

- Deleuze, Gilles. Difference and Repetition [1968]. London: Bloomsbury, 2004.

- Eckert, Herbert. “Liz Parkinson: Images of Australian Hermit Art.” Aspect 21 (June 1981): 64-68.

- Hammial, Philip with Anthony Mannix. Vehicles. Sydney: Island Press, 1985.

- Hammial, Philip. “The Australian Collection of Outsider Art.” Artlink 12, no. 4 (1992-93): 19.

- Hammial, Philip. “Outsiders Down Under.” Raw Vision 8 (Winter 1993-94): 34-37.

- Hammial, Philip. “The Australian Collection of Outsider Art.” In Australian Outsiders. Orange: Orange Regional Gallery, 2006.

- Herbert, Martin. Tell Them I Said No. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2016.

- Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. Human Rights & Mental Illness: Report of the National Inquiry into the Human Rights of People with Mental Illness. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1993.

- Jenkins, Gareth. “Anthony Mannix: ‘The Atomic Book.’” Ph.D. diss., University of Wollongong, 2008.

- “Kelly Street Kolektiv.” The Sydney Morning Herald, Metro, 25 April, 1988, 10.

- Loxley, Anne. “Woman as Goddess.” The Sydney Morning Herald, 24 July, 1988, 93.

- Loxley, Anne. “Emotional Intelligence and the Confusions of the Psyche.” In Anthony Mannix: The Beast of the Unconscious and Other Well-Known Entities. Penrith: Penrith Regional Gallery, 2009.

- Maclagan, David. “The Madness of Art and The Art of Madness.” Raw Vision 27 (Summer 1999): 20-27.

- Maloon, Terence. “Essences for the Living Dead.” The Sydney Morning Herald, 6 June, 1983, 18.

- McDonald, Anne. “Alternative Spaces Sydney.” Art and Australia 26, no. 1 (Spring 1988): 46-47.

- Milner, Jacqueline. “We Are… Have Been… Here: A Brief, Selective Look at the History of Sydney ARIs.” In National Association of Visual Arts and Firstdraft, We Are Here. Edited by Brianna Munting and Georgie Meagher. Sydney: NAVA, 2011, 62-65.

- Mannix, Anthony. “Anthony Mannix Talks to Ulli Beier.” Aspect 35 (1989): 69.

- Mannix, Anthony The Toy of the Spirit. Waratah: Puncher and Wattman, 2019.

- Mannix, Anthony. “Outsider Art.” All in the Mind. Interview by Lynne Malcolm, Australian Broadcasting Commission, March 11, 2006, audio, 30:00, https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/allinthemind/outsider-art/3305568?searchTerm=subject%3A+%22Outsider+art%22#transcript.

- Outsider Art. Sydney: The Outsider Gallery, 1982.

- Robson, Belinda. Recovering Art: A History of the Cunningham Dax Collection. Parkville: The Cunningham Dax Collection, 2006.

- Short, Susanna. “Artspace has Room for a New View.” The Sydney Morning Herald. 18 February, 1983, 12.

- Smith, Leonard. “Cure, Comfort and Safe Custody”: Public Lunatic Asylums in Early Nineteenth-Century England. London: Leicester University Press, 1999.

- “Studio 79” [advertisement]. Sydney Morning Herald, 15 August, 1981, 51.

- Topp, Leslie. “Otto Wagner and the Steinhof Psychiatric Hospital.” The Art Bulletin 87, no. 1 (March 2005): 130-156.