Destruction or Secession? Critiques of Capitalism and Nationalism at the Venice Biennale

Destruction or Secession? An Era of Disruption for the Venice Biennale

Since its genesis, the Venice Biennale has presented itself as a complex machine promoting various artistic pursuits: a platform for dreams, ideologies, and geopolitics. Devised, in part, to advance the international art market and promote tourism to Venice, the Biennale’s purpose was to assist the careers of young local artists and bring contemporary practice to those who were unable to travel. From the outset, the exhibition’s founders expressed desire to participate in artistic and cultural exchange with foreign countries; nations from around the world have sought to secure their own separate artistic and curatorial identity through the construction of national pavilions at the Biennale since 1907.

Previous research on the topic of the Venice Biennale and May ’68 has tended to focus on the protests themselves, individual artists involved, or on a few collateral exhibitions. Consideration is given neither to understanding the impact of 1968 on the succeeding 1970s iterations nor to the commercial success of the Biennale.1 Here, I weave unpublished archival documents with reviews by media outlets and testimonies from the key figures of the time. This primary research is articulated with a careful consideration of historiography at play. I begin in 1968, a moment full of youth and passion, rich in debate and protest. I examine how subsequent editions dealt with the anti-capitalist and anti-nationalist agendas circulating the Biennale and how this rhetoric was both indulged and betrayed. Behind the Biennale’s identity crisis was the revelation that the Biennale was no longer able to solely manage the now flourishing global art market, as was initially intended. Dealers and art galleries grew ubiquitous and began working in opposition to the Biennale, and all the while art making and exhibition strategies were also rapidly changing.

The Venice Biennale was a stage for the key debates of the contemporary art world of the 1960s. “Pavilions at the Venice Biennale must be destroyed, and the Gardens must be restored to their primordial state,” the Italian art critic Germano Celant proclaimed in the autumn of 1968 at Proposal for the Biennial: A Round Table, a Project (a conference held a few months after riots had taken place in Venice).2 Protesters proposed a radical secession from a consolidated art system and from the static nature of the Biennale institution. National pavilions reduced participants to “corpses,” Celant stated, and the exhibition was dead due to “creative asphyxia.” Meanwhile, he argued, the art system needed “a ring for events,” because the most interesting artists were working “in the desert, in the meadows, on the rivers and in the sea, their research increasingly ranging towards a total dimension of the world.”

At the same event, the Italian art historian Giulio Carlo Argan claimed it was necessary to end national divisions, as they were “uncontrollable.” Interferences by politicians and diplomats meant that a high calibre of all works of art could not be always guaranteed. His idea, shared by the intellectual Gillo Dorfles, was to create a single pavilion in which to display all the artists chosen by an international commission of critics, artists, and gallery owners. The publisher Bruno Alfieri even suggested modernist architects such as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Craig Ellwood, Angelo Mangiarotti, Alberto Rosselli, or Marco Zanuso could build the structure for the single pavilion. One attempt, a project by Louis Kahn for a Congress Palace that would have been a new pavilion for a utopian Biennale planned for 1969, was never built. This was perhaps for the best; plans show narrow and unserviceable spaces.3

The “invention” of the Venice Biennale in 1893 and its opening in the Saint Elena Gardens in 1895 drew inspiration from the exhibitions of the Munich Secession—which Venetian artists looked upon with admiration—and was inspired by their General Regulations. Unlike their German counterparts, who violently separated themselves from the Fine Art Academy and the official system, Venetian academics and innovative artists instead promoted this initiative together. They were not enemies, but allies. Their joint uprising was against a stale artistic environment and economic crisis, with the hope of reaffirming an artistic superiority and restoring a role of importance to Venice, which had been dominated by Austria until 1866. Venetians felt that all its glory as the “Serenissima Republic” had come to an end.

As arts-related tourism and promotion came to the fore, so too did the prominence of certain national pavilions. The Belgian pavilion was the first to be built in 1907 and has since gone through multiple alterations.4 The Venice Biennale itself has always had an open nature; it has a movable configuration that has expanded all over the city, changing with the political and cultural seasons.’

Only in the early 1970s did a sort of “youth secession” propel the potential destruction of the Biennale. Students were critical of the Biennale infrastructure being used for commercial purposes: “Venice is infected with capitalism and even the Biennale is a hostage” read a banner at the main entrance of the Fine Arts Academy in June 1968. The school was illegally occupied from March, following the youth protests in France (fig. 1).5 Protesters claimed the Biennale as a target to be defeated, arguing that it was designed just for just a “wealthy few” and to finance tourism. Officials feared the exhibition would be invaded and vandalised by protesters wanting to the Biennale to come to a halt because of its ties to Italian capitalists and elites. Indeed, many universities throughout Italy had already been occupied. One demonstration of note was at the Faculty of Architecture in Rome, where on 1 March a violent fight erupted between police and demonstrators. Albeit only for few hours, the National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome was also invaded, as was the Palazzo Reale and the 14th Triennale (both in Milan). The latter, which opened on 30 May, experienced theft, vandalism and low attendances, apparently leading to losses of well over 10 million lire (although it was publicly documented as 2.5 million lire). As such, a huge number of policemen were sent to Venice by the government to protect the Biennale. Rumors had it that there were 12,000 policemen coming, but that was revealed as a bluff. Nevertheless, riot police were armed and in view. This created widespread concern among Biennale affiliates, especially within the artist groups.6

An independent “Boycott the Biennale Committee” handed out leaflets inviting artists to withdraw their works and abandon the exhibition. Some representatives of national pavilions such as France, Norway, and the Netherlands started to suggest closing in protest at the excessive police presence. The museums and collectors who had agreed to lend works for 1968’s main historical exhibition Lines of Contemporary Research: from Informal Art to the New Structures (Linee della ricerca contemporanea: dall’informale alle nuove strutture) were uncertain as whether to lend them, fearing they could be damaged. Just a week before the opening, only forty percent of the art works had arrived. This delayed the show’s opening until July.

Lines of Contemporary Research: from Informal Art to the New Structures marked a moment of transformation for the Venice Biennale. Graphic design was given a dedicated space, as was architecture. Alongside Lines of Contemporary Research, a small exhibition of contemporary architecture hosted projects by an international line up of architects: Franco Albini, Louis Kahn, Paul Rudolph, and Carlo Scarpa. An Italian architect, born in Venice, Scarpa was foundational in the exhibition’s organisation.7 Scarpa and his fellow architects’ exhibition of contemporary architecture was arguably a challenge to the organisation, as Venice had never sought to include architecture exhibitions (the Triennale of Milan had already done so).8Alongside his curatorial efforts, Scarpa constructed an arrangement of seven sculptures titled Environment. Each work evoked the fundamental components of his typologies, which were closely aligned with minimalist and kinetic art.

Unfortunate events continued to plague the 1968 Biennale. The Biennale’s administration postponed the Central Pavilion’s opening until the summer under the rationale that any potential protests would have subsided by then. Subsequently, the esteemed Venetian painter Giuseppe Santomaso and art historian Giuseppe Mazzariol both resigned from the Commission for the Figurative Arts in solidarity with the young rebels. The famous Venetian artist Emilio Vedova formally pulled out of Lines of Contemporary Research show as another display of support.

Protests and Desires: Commitment versus Visibility

The 34th International Art Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia opened on 18 June, 1968 for press and the art industry. Protesters and police formed a congregation at the gates in the Giardini area (fig. 5). Students of the Fine Arts Academy and the Faculty of Architecture alongside students of Ca’ Foscari University held placards with slogans such as “Biennale of the wealthy, we’ll burn down your pavilions” and “Come and visit the police at the Biennale.”

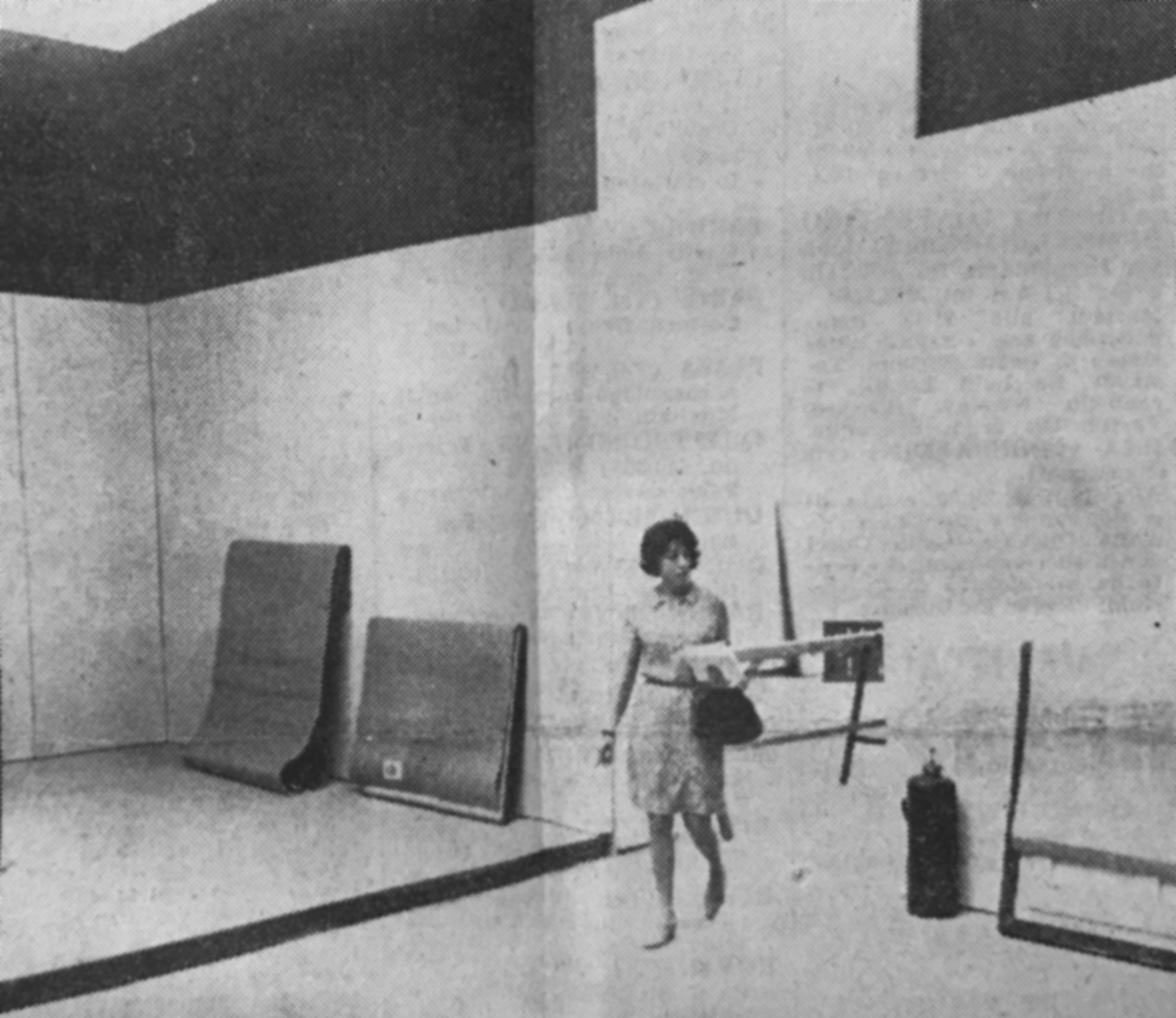

The French, Nordic, Soviet, and Japanese pavilions were closed. Amongst the Italian artists, Michelangelo Pistoletto did not even turn up to install his exhibition. During the opening, Gastone Novelli covered his sculptures with plastic sheeting and turned his paintings around to face the wall, writing “the Biennale is fascist” on the back of one. The painter Achille Perilli closed off the entrance to his room with easels.9 Novelli and Perilli transformed their rooms into a kind of a unique stand-alone installation. Protests continued outside the walls of the Biennale and throughout the streets of Venice. Around one hundred protesters converged on St. Mark’s Square and faced law enforcement (fig. 2). The following day, police resorted to violence in attempts to disperse young rioters; about forty demonstrators were beaten up that evening, some were also arrested.

Other artists boycotted the Biennale too, following the example of Pistoletto and Novelli. On 20 June, twenty-two Italian artists wrapped their works in paper or obstructed the entrances of their exhibition spaces. Only Mirko Basaldella and Mario Deluigi remained alongside Giovanni Korompay, who withdrew the day after, when a swastika was drawn on one of his paintings. Two days later, on 22 June, the day of the Biennale’s official opening, the Central Pavilion was covered in sheets and cardboard, as were the Polish, Hungarian, and Belgian pavilions. Every attempt was made to keep protesters out. The painter Emilio Vedova and composer Luigi Nono exploited their invitations to the official proceedings and organised an informal tour, singing the praises of Ho Chi Minh and Che Guevara. Dignitaries who were present at the opening ignored the pair and their supporters. Subsequently, Vedova was even challenged by a group of young people who accused him of being “part of the system,” as he had just been awarded a prize of thirty-million lire at the Montreal Expo and his work had been featured in the Biennale many times.

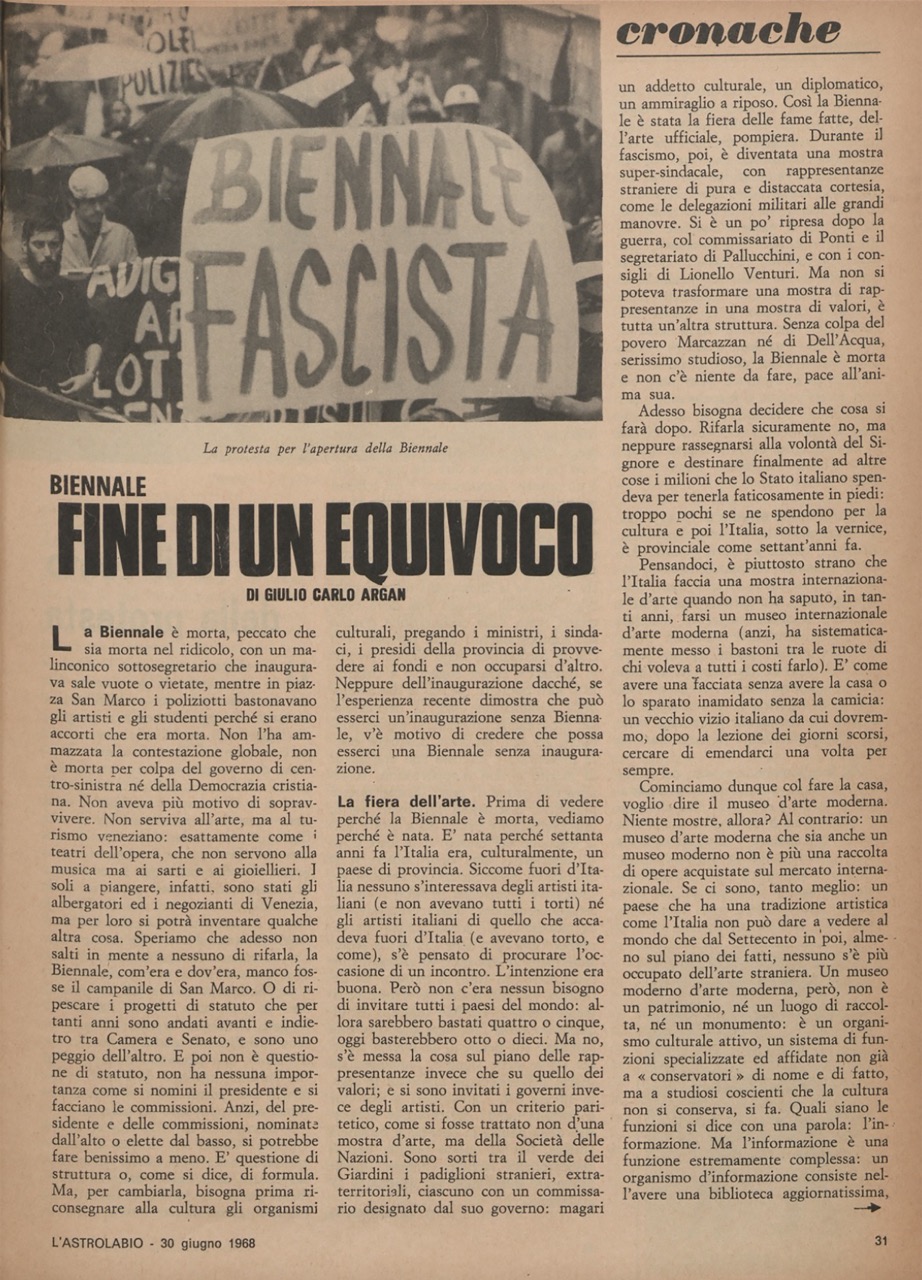

Yet everything soon returned to normal. Police gradually withdrew their presence and on 25 June, all the pavilions reopened. The Italian rooms opened on 19 July. The artists no longer saw reason to protest; their desire for visibility within the art world prevailed over the students’ ideological fervour for anti-state and anti-capitalist ideas. The art system seemingly won. However, controversy did continue to rage on in the press. Art historian-cum-politician Giulio Carlo Argan announced the death of the Biennale, describing it to a tourist trap (fig. 4). The French critic Pierre Restany suggested the Biennale should close for twenty years and Germano Celant drew comparisons between the organisation and an old ferry boat sailing indifferently on the waters of the May Revolution.10 The art critic Carla Lonzi wrote the most successful prognosis: that the protest in Venice was conducted ambiguously and encompassed the discontent of a large number of young Italian painters and sculptors who had been excluded from the Biennale.11 This reason overlapped with a larger crisis gripping every corner of society, wherein one faction demanded more equality and educational opportunities and the other, less repression by the State.12

The Ambiguous Seduction of the Art Market and a Prize to a Phantom

Building a market for contemporary art had been a key objective for the Venice Biennale since its inception. In 1932, painter Luigi Scopinich managed the sales office for just one year, only to be replaced by the charming and clever Milanese art dealer Ettore Gian Ferrari. Ferrari was appointed Director of Sales in 1942. His management was then interrupted by the burgeoning World War II, which caused the Biennale to be suspended. In 1948, another Milanese merchant replaced Ferrari, Vittorio Emanuele Barbaroux. He performed poorly. Due to low sales figures, Barbaroux was replaced by Ferrari, who took up the post again in 1950.13 At the 1968 Biennale, Ferrari claimed that the usual collectors who frequented the Biennale had deserted the opening. This seemed to contradict final reports, which revealed that 151,090 people attended over the course of the 121 days of the exhibition—including over nine hundred people at the opening. These figures were lower than the Biennale of 1966 but higher than in 1962 and 1960, with a sharp increase in the number of young people.

Regardless of the artists’ protests the market in 1968, a total of 308 works were sold. Thirty-one of the sold works were by Italian artists and 277 were by foreign artists. These figures include two drawings, Studio (1967) and Life Size Studio (1967), exhibited by Bridget Riley at the British Pavilion, which were bought by The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York for 450,000 lire and 315,000 lire respectively. MoMA also bought two Horst Janssen works shown at the German Pavilion for 380,000 lire and 40,000 lire. In both cases, these purchases took place before Riley won one of the two “Prizes of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers for a Foreign Artist” (worth 2 million lire) and Janssen won the Ministry of Education’s Graphic Art Prize (worth 1 million lire). Nicolas Schöffer’s sculpture Lux 9 (1959) won the other Grand Prize for a foreign artist. When the Biennale closed, the Italian Education Ministry purchased Lux 9 for the National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome for 5 million lire in addition to an Untitled (1965) sculpture by John Chamberlain for 3 million lire. Other significant acquisitions were made by Paolo Marinotti, Director of the International Centre of Studies on Arts and Costume at Venice’s Palazzo Grassi, who purchased Ear (1967) by the Japanese sculptor Tomio Miki for 1.24 million lire. Other notable sales included Standing Beach Figure (1965), an epoxy resin sculpture by the American Frank Gallo, which fetched 2.5 million lire, Green Watercolour (1968) by Arman (2.32 million lire), and Painting III (1968) by Rufino Tamayo (6.2 million lire). Gian Ferrari privately purchased seventeen engravings by the Brazilian artist Anna Leticia Quadros for a total of 480,000 lire.

The thirty-one Italian works that were sold also received healthy attention. Tancredi’s Oslo Composition (1962) earned 2 million lire; the painting GV 363 (1965) by Mario Deluigi went for 800,000 lire; Gianni Colombo’s environment Elastic space (1966/68) sold for 800,000 lire, unanimously won the 2 million lire award from the City and Province of Venice, and was subsequently bought by the Municipality of Bologna for its Gallery of Modern Art. The museum also acquired Leoncillo’s stoneware and enamel sculpture White Tale (1964/66) for 1 million lire. In the Venice Pavilion, reserved for the decorative arts, eighty glass objects were sold by companies such as Venini, Archimede Seguso, Fratelli Toso, Barovier & Toso, and Salviati. Twlelve of these decorative works were purchased by the Venice Savings Bank.14

The total amount of the prizes—official and unofficial, offered by the private and public sector—had risen to 18.7 million lire in 1968. But this was the last time they would be given. The panel of jurors was difficult to organise as many critics did not want to be attached to the troubled 1968 iteration of the Biennale. Eventually, a jury was formed, comprising of Emile Langui (President), René Berger, Cesare Brandi, Maurizio Calvesi, Robert Jacobsen, Dietrich Mahlow, and Ryzard Stanislawksi. The jury group wrote a letter expressing the hope that prizes would be “abolished” in order to improve the Biennale’s democratic credentials.15 The consequence was that there would be no awards for eighteen years. This was another small gesture of the Biennale’s secession from capitalist value systems and national competition, even if “The Golden Lion” and other minor prizes would be established once again in 1986—albeit in a different social and political climate.

The 1968 Biennale had another unprecedented note or departure from tradition. One of the main prizes was awarded posthumously to the young artist Pino Pascali. Pascali passed away at the age of just thirty-three on 11 September of that year after a motorcycle accident. The Biennale ended on 20 October. According to Article 7 of the Regulation, prizes could not be given to dead artists. The jury, however, found a diplomatic compromise, taking into consideration Pascali’s immense talent and the support given to him by Palma Bucarelli, the influential Director of the National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome. Taking advantage of the lack of a definitive legal interpretation of the definition “living artist,” jurists voted five against two to consider “any artists still living at the opening of the exhibition fully eligible for prizes.” Pascali was posthumously awarded the 1968 Sculpture Prize. Japan’s Jiro Takamatsu controversially won the 500,000 lire Carlo Cardazzo Award—the first time an artist from Eastern Asia had won the prize. The “Prizes for Decorative Arts” were decided by a different, sector-specific jury. Among them, the 2 million lire prize from the Gavina SpA was awarded ex aequo to Mario Deluigi and the Belgian Luc Peire. Carlo Scarpa was involved with Gavina SpA’s and a close friend of Deluigi. At the time, Scarpa had been staging exhibitions for the Biennale for some thirty years, mainly in the Central Pavilion, and this proved to be his penultimate edition. He had little sympathy for the young artists’ protests and was angry at them for desecrating the rooms he had prepared for their works of art. Despite the criticism and the fact that it had become difficult for art institution to manage their contributions the international art market, due to the influence of foreign galleries and the emerging role of critics and curators (as opposed art historians), the Biennale still proved to be resolutely saleable.

Despite the chaos, the 1968 iteration of the Venice Biennale was successful because, ultimately, the protests functioned to promote and build interest in the exhibition—an unexpected benefit. Moreover, for the very first time, there was a specific international group exhibition—Lines of Contemporary Research—alongside the national pavilions, which acted as a fulcrum of the event. This was the beginning of what we think of as today’s Biennale: a major international show helmed by a single curator.

Utopia, Technology and Uncertainty: the Biennale as an Experimental Laboratory

Commitment and understatement were the key words in the 1970 edition of the Biennale. The opening took place without ceremony and due to the personal preferences of the new director, Umbro Apollonio, Professor of History of Contemporary Art at the University of Padua and the new commissioners, Bruno Munari, Dietrich Mahlow, and Luciano Caramel, the exhibition was particularly dedicated to optical art and the role of technology in art.16 Experimentation, public engagement and pedagogy dominated: one section of the Central Pavilion was devoted to a printing workshop set up by the artist Gianfranco Tramontin, who called upon twenty-six international artists to work with various techniques ranging from engraving to photocopying. Another laboratory was held outside the USA Pavilion by participating American artists.

The exhibition therefore featured a plethora of “unsellable” artworks—more than the previous edition. These including Biotron (1970) by Luis Fernando Benedit, a plexiglass and metal hive filled with 4,000 real bees and acrylic flowers containing honey. Another notably uncommercial work was 7 Spheres with Siren (1970) by Sergio Lombardo. 7 Spheres with Siren had been shown at the Biennale de Paris the previous year and consisted of plastic balls, one metre in diameter, which emitted sound when approached (one even caught fire). Maurizio Mochetti’s A>B (1970) consisted of two white and empty rooms. A bright dot was projected onto the walls of the first space and the sound of an arrow being released could be heard in the second. Davide Boriani and Livio Castiglioni constructed a “distorted” room entitled Space of Perceptual Stimulation (1970). It consisted of a curved space with an ellipsoidal shape, made from expanded polyurethane and sodium lamps, where structures emitted light and sound signals. These structures confused spectators and contorted their spatial awareness, thus creating unusual sensory stimulations typical of scientific experiments.

Acquisitions were generally small works—engravings and drawings—and not particularly significant. However, Josef Albers’ Constellation VII (1958) was sold for 235,000 lire and the Finnish painter Juhani Linnovaara sold six paintings, including one to the Obelisco Gallery in Rome. The Ministry of Education made six purchases for the National Gallery of Modern Art, including the sculptures LXX-ALP/1 (1969) by the Yugoslavian artist Dušan Džamonja for 6.325 million lire, Interrogation of the Partisan (1962) by the Polish artist Władysław Hasior for 4.4 million lire, and Dark Spiral (1970) by German artist Günther Uecker for 2.342 million lire. Decorative arts also continued to be successful: the Venetian ceramicist Neera Gatti sold fifteen necklaces and the Venetian Savings Bank bought seven glass works, including two luminous panels by the Fratelli Toso for 22,000 lire each.17

In 1970, the sales office was run by the Biennale administrative department. It was led by Luigi Lion, who was already working for the institution. Gian Ferrari had stepped back, believing international galleries preferred to not have any kind of intermediary and that supervising sales was becoming more and more complicated. Where the campaigns against capitalism had failed in 1968, the early onset of globalisation in 1970 succeeded. The immense difficulty faced by an institution seeking to control the promotion and trade of works of art from so many different countries became clear. The Biennale became less of a salon or a place for selling art and more of an international cultural event. The Italian state had to provide more funding and the art market had to move further away from the Biennale.

After the chaos of 1968, the Biennale remained in a state of emergency. This was abated in 1972, when Mario Penelope was temporarily appointed special deputy commissioner and managed to bring expenses down to 200 million lire. In the same edition, the Biennale had for the first time a section for video works and a show outside the Giardini area; an International Sculpture Exhibition was arranged between various Venetian squares and the Doge’s Palace. Relational work became more common. Within the Central Pavilion, the Italian section titled Opera o comportamento’ (Work or behaviour) saw two different critical visions realised. The first was deployed by Renato Barilli and Francesco Arcangeli. In Real-time Display no. 4. Leave a Photographic Trace on These Walls of Your Passing (1972), Franco Vaccari set up a photo kiosk with a sign asking visitors to add their pictures to the wall, creating a sort of memory machine to reflect on the value of time and artistic creation. Germano Olivotto used photographs to document his Substitutions (1969–72) by placing neon tubes on trees in the countryside, as if they were artificial branches. He also featured works consisting of those photographs accompanied by small neons, Indicazioni. Three were sold for 640,000 lire each (one of them went to Renato Cardazzo, the brother of the Venetian gallerist) and another one sold for 800,000 lire. Mario Merz created a performance in the lagoon with a boat. Merz assembled one of his now famed igloos, Fibonacci Igloo (1972), complete with neon lights and constructed from small cushions.18 Gino De Dominicis sparked controversy on the opening day with his tableau vivant Second Solution of Immortality (The Universe is Immobile) (1972). The work comprised of a man with Down Syndrome watching over a stone, a ball and a square drawn on the ground. This was an inappropriate choice given the perceived exploitation of the participant. After the uproar, De Dominicis kept his gallery space locked up until 26 June and set up a video directed by Gerry Schum, who elsewhere at the Biennale had his own exhibition of videotapes in the Central Pavilion. The video features a close-up of the artist staring into the lens for 27 minutes, entitled Gino De Dominicis Can See You (Third Solution of Immortality) (1972). Additionally, the Belgian Mass Moving Group released 10,000 butterflies into Saint Mark’s Square, having kept them for two weeks in a sort of spectacular white incubator. These works caused widespread civilian concerns and were, indeed, very unsellable pieces of art.

By 1972, the sales office had been handed over to the Union of Modern Art Dealers, an organisation represented by the Milanese gallery owner Zita Vismara. It was the first time a woman would play such a significant role in the Biennale. In December 1971, Mario Penelope had offered the position to the Union, which was presided over by Gian Ferrari. After four months of silence and misunderstanding, as well as a row between Gian Ferrari and the curator Marco Valsecchi (who preferred the dealer Renato Cardazzo), negotiations had fallen by the wayside. In May, not long before the opening, Zita Vismara was offered the job. She negotiated a commission of 5% on the sale price, although she failed to get the Biennale to also pay for the office’s running costs and a typist. Vismara oversaw the sale of a marble altar by Pietro Cascella for 10 million lire; the painting Tropical Fruit (1969) by Wilfredo Lam for 13.1 million lire; the sculpture Roncesvalles (1968) by Nino Franchina to the Ca’ Pesaro museum for 2.2 million lire; four photos combined with a neon tube entitled Indicazione (1972) by Germano Olivotto for 640,000 lire each; twelve sculptures by Pietro Consagra titled One millimeter for 150,000 lire each; a silkscreened Marilyn (1967) by Andy Warhol for 650,000 lire; a Claes Oldenburg lithograph Proposed Monument for Kassel (1968) for 320,000 lire; the Vega 222 (1970) screen-print in colors by Vasarely for 330,000 lire; the tempera painting Rio (1971) by Giulio Turcato for 350,000 lire; many ceramic design works by Alessio Tasca and over 149 graphic works. Some of the graphic works were oversold after inaccurate recording of the numbered editions.

In November of 1972, a letter from the Transport and Treasury Department of the Venice Biennale relayed that “purchasers complained (sometimes bitterly) because so long had passed since the Exhibition had closed and they still had not received all the works.” Engravings by forty artists, including Solari and Alekinsky, went missing. Vismara was forced to write forty-two letters in two days that were sent across the globe from Venice to Paris to Osaka, asking printmaking editors for new print editions. It also turned out that her assistant, Maria Silva Zanini, had miscalculated prices when converting foreign currencies.19 After 1972, the sales office finally closed. The primary reason was the immense difficulty of managing a truly international art market. A lingering goal of May ’68 had finally been met; the Biennale had been extricated from the market.

Biennales that Disappear and Reappear, Expand and Metamorphise

After 1972, the Venice Biennale seemingly disappeared until 1976, although its activities continued. In 1973, its statute changed, and it took some time to reset the exhibition’s remit. In 1974, a small edition was devoted to Chile, celebrating the country’s cultural heritage and protesting the Pinochet dictatorship. A special show within the Central Pavilion was dedicated to artists restrained by Francisco Franco in Spain. These activities seemingly reduced the outward nationalism exerted within the pavilions of individual countries.

The Biennale—following documenta in Kassel—turned its focus towards the present instead of celebrating established values. It became less common to see weighty exhibitions of Old Masters or artistic movements curated by art historians with the aim of educating the public (for example, the Impressionists exhibition in 1948 or Lines of Contemporary Research in 1968). Instead, the Biennale preferring group exhibitions of contemporary artists curated by militant curators—a great innovation of the 1970s that in turn led to the Biennale being assigned to a single curator. Spaces outside the Biennale also began to be used, beginning its expansion all over the city. In 1974, an extra exhibition at the Magazzini del Sale venue was dedicated to the photographer Ugo Mulas, who mapped Biennales from 1954 to 1973. In 1975—a year when there was no Biennale but the idea was floated to make it an annual event permanently—Venice hosted The Bachelor Machines, curated by Harald Szeemann (the exhibition had previously shown in Bern, Switzerland) and Proposals for the Molino Stucky, by the architect Vittorio Gregotti. These transformations also softened the questions of national belonging and the aggressiveness of the art market.

In 1976, the 37th Venice Biennale, titled Environment, Participation, Cultural Structures, gave space to special exhibitions for decorative arts, design and architecture and featured glass, graphic design, photography. The liveliest and most debated sections were those by curators such as Environment/Art: From Futurism to Body Art by Germano Celant. In the Central Pavilion he staged a re-enactment of historical environments created by the avant-gardes and neo-avant-gardes. Celant also invited thirteen artists to create their own site-specific works. This operation helped to position him somewhat as both an art historian (which he never was) and a curator, granting himself a critical distance from his colleagues whilst simultaneously being publicly hailed as the inventor of the Arte Povera group.20 A truly breakthrough moment was a space run by the art critic Tommaso Trini, Attivo, at the former shipyards in Giudecca district. During the opening days, Marina Abramovich’s first performance with Ulay, Relation in Space, featured alongside other international and Italian artists.

The protests of 1968 had built a new cultural imagination, enhanced the concept of collectivity and encouraged reflections on ecology. In 1978, the exhibition celebrated a connection with nature in one of the most successful and utopian editions. Although the Biennale still seemed to be in crisis at a management and political level, it was undergoing profound transformation and modernisation in line with international trends, presenting contemporary art, video works, and installation art. The role of the curator became increasingly important, to the detriment of that of the art historian. New powers were taking over.

Completely erasing the Venice Biennale from the artworld’s map was no longer the question, as it had been in 1968. Instead, the event emerged as the exemplar for the emerging circuit of biennials and triennials throughout the world.21 However, in 1990, the physical buildings housing the Biennale were at risk.22 Over the years, the buildings had been continuously modified, both inside and outside (most notably in Carlo Scarpa’s interventions to the facade in 1966 and 1968). At the previous Venice Biennale of Architecture, professor and editor Francesco Dal Co had launched a competition for a new pavilion. Amongst the twelve projects presented, the winner was designed by Francesco Cellini, who had already worked at the Biennale with the art historian Maurizio Calvesi in 1984 and 1986. Apart from the Sculpture Garden, designed by Carlo Scarpa inside the existing pavilion in 1952, and the round hall in the entrance with the dome painted by Galileo Chini in 1903, everything was to be destroyed. The 1990 Biennale, arranged by Giovanni Carandente, was threatened with being cancelled as these major works were planned to take place.23 Ultimately, the proposed pavilion was never built. However, amidst these building uncertainties and with unstable financing, the 1992 Biennale moved to 1993.

The practice of using the Central Pavilion as a venue for exhibiting Italian artists—and for hosting other nations without a location or for special exhibitions—ended in 1999. Instead, Harald Szeemann’s exhibition Dapertutto = Aperto over all = Aperto par tout = Aperto über all took its place. This created something more akin to a diaspora space. The title of Szeemann’s show was inspired by Aperto (meaning open) and by his desire to include young artists. In 2009, at the 53rd Biennale, titled Fare Mondi [Making Worlds] and curated by Daniel Birnbaum, an Italian Pavilion found its place once again at the end of the Corderie in the Arsenale. The Venice Biennale’s original aims (stretching back to 1895) were to promote the role of Venetian and Italian art on the global stage. As a result of the turbulence of the Biennales of the twentieth century, this gambit shifted. Instead, the role of the curator and an emphasis on international art became the crux of the Biennale.

The utopian aims of protests in May 1968 were (somewhat naively) to defeat global capitalism, end oppression by a centralised government, and contest nationalism in contemporary art. By the 1990s, however, more nationalism than ever shaped the Biennale. More and more nations demanded an independent pavilion, and the exhibition spread all over the city in rented spaces authorised by the Biennale organisation. As with all secessions, so new and mesmeric when first planned, the strange events of 1968 later became fixed and recognisable. Yet the magic of the original ambitions remain in the retelling of the history.

-

Lawrence Alloway, The Venice Biennale 1995-1968: from Salon to Goldfish Bowl (London: Faber and Faber, 1968); Pascale Puma Budill on, La Biennale di Venezia dalla guerra alla crisi (1948–1968) (Bari: Palomar, 1995). ↩

-

“Proposte per la Biennale. Una tavola rotonda, un progetto,” mETRO 15, August 1968, 39–47. The event was organised in Venice by the art magazine mETRO. ↩

-

“Tavola rotonda,” mETRO 17, September-October 1968, 38–54; “Editorial,” mETRO 12, February 1967, 5–6. ↩

-

Giandomenico Romanelli, Ottant’anni di architettura e allestimenti alla Biennale di Venezia (Venezia: Archivio storico delle arti contemporanee, 1976); Marco Mulazzani, I padiglioni della Biennale. Venezia 1887–1993 (Milano: Electa, 1995); also see Alemani, Cecilia, Alberto Barbera, Marie Chouinard, Ivan Fedele and Antonio Latella, The Disquieted Muses. When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History (Venice: La Biennale di Venezia, 2020). ↩

-

See archival materials at La Biennale di Venezia, ASAC (Archivio Storico delle Arti Contemporanee). ↩

-

Pascale Puma Budill, La Biennale di Venezia dalla guerra alla crisi (1948–1968);

Stefania Portinari, Anni Settanta: La Biennale di Venezia. (Venice: Marsilio Editore, 2018). ↩

-

Philippe Duboÿ, Carlo Scarpa. L’arte di esporre (Monza: Johan & Levi, 2016); Stefania Portinari, “1968. XXXIV Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte di Venezia,” in Carlo Scarpa e la scultura del ‘900, ed. Guido Beltramini (Venice: Marsilio, 2008); Orietta Lanzarini, Carlo Scarpa. L’architetto e le arti. Gli anni della Biennale di Venezia. 1948–72 (Venice: Marsilio Editori, 2003); this exhibition is what led to the first Biennale Architettura (as the International Architecture Exhibition) that expanded the Biennale into Arsenale. ↩

-

The only exception to this was one small retrospective dedicated to the German architect Erich Mendelsohn’s drawings in 1960, held inside the Central Pavilion. Here Central Pavilion refers to what we now know as the Italian Pavilion. ↩

-

Gigi Ghirotti, “La Biennale è stata aperta ai critici, i “filocinesi” dispersi dalla polizia,” La Stampa, 19 June 1968; Gastone Novelli, Gastone Novelli (Verona: Studio La Città, 1988). ↩

-

Giulio Carlo Argan, “Biennale/Fine di un equivoco,” L’Astrolabio, 30 June 1968; Germano Celant, “Una Biennale in grigio verde,” Casabella no. 327 (August 1968): 52–56; Pierre Restany, “Il suicidio della Biennale,” Domus 466 (September 1968): n.p. ↩

-

Giovanna Zapperi, Carla Lonzi: un art de la vie – Critique d’art et féminisme en Italie (1968–1981) (Paris: Les Presses du Réel, 2019). ↩

-

Looking internationally, the 1968 protests in Venice share resonance with the 10^th^ International Art Biennial of São Paulo in 1969. Colloquially titled the “Biennial of the Boycott,” the biennial was heavily scrutinised by artists participating in the project. ↩

-

Alessandro Alfier, “La vendita di opere d’arte alle edizioni della Biennale di Venezia dal 1920 al 1942,” in Donazione Eugenio Da Venezia. Quaderno n. 17. Atti della Giornata di Studio che si è tenuta alla Fondazione Querini Stampalia il 14 dicembre 2007, eds. Giuseppina Dal Canton and Babet Trevisan (Venice: La Biennale di Venezia Foundation, ASAC Historical Archive of Contemporary Arts, Querini Stampalia Foundation and Civic Museum of Rovereto, 2008) 94–114;

Claudia Gian Ferrari, “Le vendite alla Biennale dal 1920 al 1950,” in Venezia e la Biennale. I percorsi del gusto, ed. Giandomenico Romanelli (Milano: Fabbri, 1995), 69–94. ↩

-

See the ASAC, Historical Archive, “Sales Office: Register 67,” XXXIV Biennale 1968, Decorative Arts. Also see Biennale di Venezia, Catalogo della XXXIV Esposizione Biennale Internazionale d’Arte Venezia ( Venice: Fantoni Artegrafica, 1968). ↩

-

Prizes were usually assigned at the opening ceremony, however were postponed until October. See ASAC, “Sales Office: Register 67,” 1968. ↩

-

In 1970, while the Biennale’s new statute was being discussed in Parliament, management positions changed: the art historian Gian Alberto Dell’Acqua was appointed as “Commissioner” (an honorary position), Apollonio as “Director” (a role that never officially existed before, established to give him the leadership), while Luigi Scarpa acted as “Secretary General,” an assignment that previously meant being the main curator and manager of the Biennale, but at this point assumed a mere administrative role. ↩

-

ASAC, Historical Archive, “Sales Office: Register 69,” XXXIV Biennale 1970, Foreign Works of Art. ↩

-

Mario Merz and Caroline Tisdall, “An Interview by Caroline Tisdall,” Studio Interview (January/February 1976): 11–16 ↩

-

ASAC, Historical Archive, “Sales Office: Registers 72,” Sales of Works of Art. ↩

-

In 1972, Celant officially declared that the Arte Povera group (which he had so named in 1967) had come to an end and that each artist was to continue its research alone; this was a consequence of exhibitions his protégés had held in Berne and New York, as well as in Italy, outside his curatorship: see Celant, “Una Biennale in grigio verde,” 52–56. ↩

-

Filipovic, Van Hal, Østebø, 2010; Vogel, 2010; Gardner and Green, 2016. ↩

-

The Palazzo Pro-Arte, was renamed the Italian Pavilion, then retitiled the Central Pavilion to finally be named the Italian Pavilion until 1974. ↩

-

ASAC, Historical Archive, “Visual Arts: b. 473/2: Report of the Congress at Hotel Europa, Venice, 10th-11th March 1990: 2–3. ↩

Stefania Portinari is Associate Professor in History of Contemporary Art at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Italy. After completing an M.A. in Cultural Heritage Conservation, she undertook graduate studies at the University of Florence, completing a PhD in the History of Art. She has worked at the Soprintendenza for Cultural and Artistic Heritage of Venice and as an independent curator.

Her research centres on art, design and architecture history in the nineteenth and twentieth century. She has extensively studied the history of Venice Biennale and recently curated an exhibition of portraits of women in the 1910s and 1920s, including works by Gustav Klimt and Felice Casorati.

Bibliography

- Biennale di Venezia. Catalogo della XXXIV Esposizione Biennale Internazionale d’Arte Venezia. Venice: Fantoni Artegrafica, 1968.

- Alambert, Francisco and Polyana Canhête. As Bienais de São Paulo da era dos museus à era dos curadores (1951-2001). São Paulo: Boitempo, 2004.

- Alemani, Cecilia, Alberto Barbera, Marie Chouinard, Ivan Fedele and Antonio Latella. The Disquieted Muses. When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History. Venice: La Biennale di Venezia, 2020.

- Alfier, Alessandro. “La vendita di opere d’arte alle edizioni della Biennale di Venezia dal 1920 al 1942.” In Donazione Eugenio Da Venezia. Quaderno n. 17. Atti della Giornata di Studio che si è tenuta alla Fondazione Querini Stampalia il 14 dicembre 2007, edited by Giuseppina Dal Canton and Babet Trevisan, 94-114. Venice: La Biennale di Venezia Foundation, ASAC Historical Archive of Contemporary Arts, Querini Stampalia Foundation and Civic Museum of Rovereto, 2008.

- Alloway, Lawrence. The Venice Biennale 1995-1968: from Salon to Goldfish Bowl. London: Faber and Faber, 1968.

- Arcangeli, Francesco and Renato Barilli. Comportamento: Biennale di Venezia 1972: Padiglione Italia. Milan: SilvanaEditoriale: 2017.

- Argan, Giulio Carlo. “Biennale/Fine di un equivoco.” L’Astrolabio. 30 June 1968.

- Budillon Puma, Pascale. La Biennale di Venezia dalla guerra alla crisi. 1948-1968. Bari: Palomar, 1995.

- Celant, Germano. “Una Biennale in grigio verde.” Casabella no. 327 (August 1968): 52-56.

- Celant, Germano. Arte Povera. Storia e storie. Milan: Electa, 2011.

- Duboÿ, Philippe. Carlo Scarpa. L’arte di esporre. Monza: Johan & Levi, 2016.

- Editorial. mETRO 12. February 1967.

- Ferrari, Claudia Gian. “Le vendite alla Biennale dal 1920 al 1950.” In Venezia e la Biennale. I percorsi del gusto, edited by Giandomenico Romanelli, 69-94. Milano: Fabbri, 1995.

- Filipovic, Elena, Marieke van Hal and Solveig Øvestebø, eds., The Biennial Reader. Stuttgart: Hatje Cantz, 2010.

- Gardner, Anthony and Charles Green. Biennials, Triennials, and Documenta: The Exhibitions that Created Contemporary Art. New York: Wiley-Blackwell, 2016.

- Ghirotti, Gigi. “La Biennale è stata aperta ai critici, i “filocinesi” dispersi dalla polizia.” La Stampa. 19 June 1968.

- Lanzarini Orietta. Carlo Scarpa. L’architetto e le arti. Gli anni della Biennale di Venezia. 1948-72. Venice: Marsilio Editori, 2003.

- Merz, Mario and Caroline Tisdall, “An Interview by Caroline Tisdall.” Studio Interview (January/February 1976): 11-16.

- Mulazzani, Marco. I padiglioni della Biennale. Venezia 1887-1993. Milano: Electa, 1995.

- Novelli, Gastone. Gastone Novelli. Verona: Studio La Città, 1988.

- Portinari, Stefania. “1968. XXXIV Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte di Venezia.” In Carlo Scarpa e la scultura del ‘900, edited by Guido Beltramini, n.p. Venice: Marsilio, 2008.

- Portinari, Stefania. Anni Settanta: La Biennale di Venezia. Venice: Marsilio Editore, 2018

- “Proposte per la Biennale: Una tavola rotonda, un Progetto.” mETRO 15. August 1968.

- Restany, Pierre. “Il suicidio della Biennale.” Domus 466 (September 1968): n.p.

- Romanelli, Giandomenico. Ottant’anni di architettura e allestimenti alla Biennale di Venezia. Venezia: Archivio storico delle arti contemporanee, 1976.

- Rota, Tiziana. La galleria Gian Ferrari 1936-1996: 60 anni di storia dell’arte contemporanea nel lavoro di due protagonisti. Milan: Charta, 1995.

- “Tavola rotunda.” mETRO 17. September-October 1968.

- Vogel Sabine. Biennials - art on a global scale. Vienna-New York: Springer, 2010.

- Zapperi, Giovanna. Carla Lonzi: un art de la vie — Critique d’art et féminisme en Italie (1968-1981). Paris: Les Presses du Réel, 2019.