1900—Pyrrhic Victory The Press Campaigns Surrounding the Faculty Paintings

Ludwig Hevesi noted with surprise how commendably modern he found the fourteenth exhibition of the watercolourists’ club, held in the Künstlerhaus, in terms of both its installation and the works on show.1 At the centre of the composition stood the chateau design and interiors jointly conceived by the architect Josef Urban and the painter Heinrich Lefler for Count Charles Esterházy; the chateau, to be erected in the village of Szent Ábrahám in Pozsony County (now Abrahám, Slovakia), bore the mellow, organic lines of the Jugendstil. In his appraisal, however, the critic argued that the two modern experimenters in the Künstlerhaus, despite all appearances, were not free-minded stylistic innovators, but merely imitators of the style of the Secession. In minute detail he picked apart the faults, both large and small, in the designs for the interiors, and he refused to place Urban and Lefler’s artistry on the same level as the works of Olbrich or Hoffmann.2 With this critical manoeuvre, he lent his support to the battle for artistic supremacy that had been launched in spring 1898 by members of the Secession and by Hermann Bahr, when the group contended that in Vienna, they alone, the artists of the Secession, were the exclusive, authentic custodians of experiments in style that could be interpreted as Secessionist. By means of an indirect response, artist and art critic Adalbert Seligmann published a reader’s letter, which effectively reinforced his earlier stance: the Secession (Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs) and its devotees had turned into a clique that ostracized all other modern endeavours, branded all rivals as uniformly inauthentic, and claimed the accolade of modern art solely for themselves.3 In cool and precisely analytical, liberal tones, his writing, illustrated with specific artistic examples, defended the right of every individual member of the artistic community to make his or her own judgement about what they regarded as modern. Seligmann vehemently denounced the “new” practice among critics to classify artistic achievements as modern or false depending on which association the given artist belonged to. From the debate it transpired that the Secession was pursuing a hardline policy of preserving its interests—not only against conservatives, but also against all other modern artists who had not joined them—in order to dominate the Viennese art market, and Hevesi was playing an active part in supporting these efforts.

In this atmosphere of rivalry and tensions within the profession, the Künstlerhaus organized the debut exhibition of a new art society, the Hagen-Bund (still written this way at the time). Remaining part of the Künstlerhaus, a group of talented young artists formed a close alliance, signifying that they espoused similar artistic principles. The chamber exhibition generated a favourable impression and was greeted warmly by Hevesi and Seligmann.4 This phenomenon was just one element of the rapid process of differentiation that came about, in which a number of smaller art groupings sought to carve out their own profile on the art scene, their own federation of defence and defiance, in order to survive in the battle for supremacy that increasingly characterized artistic life in Vienna.5

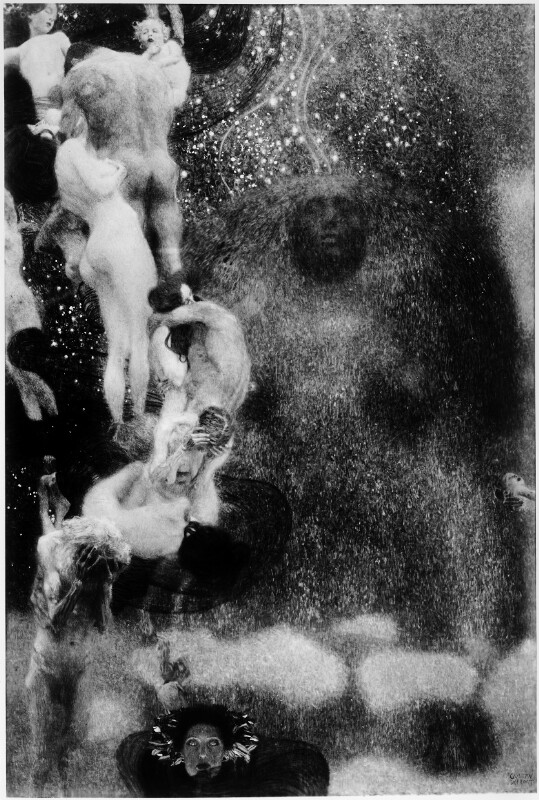

The next (sixth) exhibition of the Secession took place on “neutral soil,” with Japanese art as its focus, precluding any scope for local stylistic debates. The scandal did not erupt until the (seventh) spring exhibition of the Secession, which had at its centre Gustav Klimt’s Faculty Painting, Philosophy (fig. 1).

The Confrontation Escalates: Philosophy

The events themselves are well recorded in the literature.6 The debate surrounding Klimt’s painting not only engulfed the art community, but the entire cultural scene of Vienna, and soon took on a cultural, political and even ideological dimension.

In the last forty years or more of intensive research into the Vienna Secession, the art history literature has tended to take the perspective of the advocates of modern art, building up a narrative of “victim culture,” with Klimt as the victim, and casting the entire debate as a fight for artistic freedom.7 The other main aspect of the literature on the Faculty Paintings, constituting the majority of interpretations, is its focus on the erotic message of the pictures, in which the works are viewed as documents of the sexual identity crisis that burst to the surface so forcefully at the turn of the century (this is evident in the work of W. Hofmann, C. E. Schorske, Gottfried Fliedl, and many others who followed in their wake). The sphere of sexuality was indeed a crucially important element in the complex history of Vienna’s “project of social modernization,” and one that appears particularly dominant due to the activities of Sigmund Freud and Otto Weininger, but even in the art world it was not the only factor of note.8 Even though sexuality did play a major role in the negative reception of the paintings (the authors always put the blame on the conservatism within society and on bourgeois values), this was not the only intellectual and emotional objection, and in the case of the two most disputed works, Philosophy and Medicine, it was perhaps not even the most significant one. While the literature quotes many contemporary critics who praised and embraced the artistic solutions in the paintings and the ideas and content they conveyed, hardly any mention, if at all, is made of the dissenting voices. Instead, the most important texts, such as Carl E. Schorske’s poetic and literary interpretation of the pictures, are reiterated in the new readings, and the notions of Freud, Schopenhauer and Nietzsche are assumed to lie behind the ambivalent painterly solutions and the enigmatic artistic forms, which prove so suitable for such interpretations because they are so open. Consequently, the literature has come to regard almost as a fact the contention of Carl E. Schorske that the essence of Viennese modernism was the Oedipal rebellion of the younger generation, which derived from the crisis caused by the self-image of liberalism.9 The sons were thus rebelling not only against their fathers’ worldview, but also against their elders’ traditions and discourses. This, at least, is confirmed by the articles published in the Secession’s periodical, Ver Sacrum. The message, wrapped up in ancient legends, uses aphoristic slogans and catchy phrases, and refers incessantly to artistic freedom, but is silent on the other main aim of the group: the steps they took in connection with the art market.

Werner Hofmann’s sophisticatedly analytical and philosophically thought-provoking book, written a good decade before the Klimt cult exploded into an international phenomenon,10 perceptively interprets the Faculty Paintings (and Klimt’s later allegorical works) as “pictures of humanity.”11 Hofmann attributes the Secessionist shift in style in Klimt’s oeuvre to the fact that female figures increasingly began to serve as the means by which viewers could empathize and identify with the human message of pictures. This process was consistently pursued in the first two Faculty Paintings. Most of the figures depicting the suffering of humanity are women, while the men are faceless. Similar to allegory, the symbolic vision no longer has a determinable historical time, but instead is general and eternal. That is, it ingeniously captures the almost unexamined floating of human life in the cosmos, reduced to biological existence and to fate. All that is represented in the human figure is its most basic and general level as a biological, that is, natural being; the naked bodies also serve this purpose of timelessness and generalization.

The nudity in the composition of Philosophy can hardly be interpreted as a painterly solution for emphasizing sensuality. Rather, it conveys the vulnerability of the individual. The dominance of Eros and Thanatos in the literature on turn-of-the-century Viennese painting is still valid and unbroken, but it cannot remain the sole paradigm for analysing the paintings and works. This theme has a long-standing cultural tradition, and was entirely acceptable to the liberal approach to art. It was not only the boldly new and taboo-shattering depiction of Eros and of sexuality as a whole, but—to continue with the classical terminology—the hubris that typified the art group (the arrogance of artistic privilege) that caused a large part of Vienna’s intellectual elite to turn its back on the art of the Secession at this time. The sense of privilege that pervaded the writings of Hermann Bahr, Hevesi, Carl Moll and Ernst Stöhr was seen as disproportionate and ethically objectionable. Many people were particularly offended by the hurtfulness of Bahr’s rhetoric. Even in 1898, during the first incursion of the Secession, Bahr had chosen as the motto to go above the Nuda Veritas adorning his study a quotation from Schiller implying that only a select few were worthy of understanding art.12

The present reading not only takes the principles of the pro-Secession “lobby” into consideration, but also other criteria. Hitherto, the literature has largely ignored those contemporaries who detracted from the cult of modernity, or has tended to brand their motives as conservative and retrograde, even without analysing their texts, examining their arguments or attempting to uncover the fundamental reasons underlying their objections.13 In this historical reconstruction, we will now try to understand the logic of the then-critics of the Faculty Paintings, and to examine the tactics and tools deployed by both camps to assert their claims. We will not only investigate the actions taken at the time by cultural policy and state patronage (a subject that has already been successfully dealt with in the literature), but, relying on contemporary press sources, we will also assess the reactions and the criticism of laypersons, art lovers, and most importantly, as they were most directly affected, the professors at the university. In this way, Hevesi’s extraordinary and prominent propagandistic role may be revealed in a different light.

On the day of the opening, 8 March, Hevesi (who had also written a brief explanatory text on the picture in the catalogue)14 published his first, laudatory article on the work, aimed at setting the tone for its reception, in which he expounded at length on the merits of Klimt’s Faculty Painting. Far from being easy reading, his eloquent text is filled with metaphors and lyrical similes. He writes:

Klimt’s Philosophy is a great vision which describes, one could say, a fantasy of the cosmos. We are presented with the all-embracing chaos from which Life has wrestled itself free, or continues to struggle to do so, Life as an eternally flowing and uninterrupted series of forms that materialize and dematerialize.15

Hevesi dedicates the greatest amount of space to the incorporeally sphinx-like “universal enigma,” the vision-like figure who embodies the mystery of the world, while he describes in the briefest terms the most complicated part, the flow of people drifting in the cosmos. At the end of his analysis, led either by an abundance of caution or perhaps by foreboding, he adds:

Klimt … set himself the task of painting an allegory of the most secret of sciences and has found the authentic painterly solution for that task. This solution will not of course be understood at first—rather it will only be sensed; but we have confidence in our public, which, over the last three years, has so markedly expanded the scope of its empathy. It will engage with and appreciate this important work.16

Hevesi somewhat overestimated the pliability of public taste. Within a week, Vienna’s community of art devotees was in uproar, and the greatest outrage stemmed from the group of intellectuals who felt most resentful about the content of the painting, the professors at the university. Supporters and detractors of the work clashed with unprecedented ferocity. Though the fully committed modernists among the journalists did all they could to foster the success of the painting, they were now met with harsh resistance even from their otherwise most softly spoken colleagues. On Monday 12 March, the regular art correspondent of the Wiener Zeitung, the Budapest-born Armin Friedmann, wrote a long report on the work.17 Friedmann begins his analysis of the painting with the lines written in the catalogue. “With or without interpretation the painting is confusing in many directions. According to one’s disposition one may see in it everything or nothing. That will depend on the acuteness and wit of the interpreter.” This ambivalence was what caused the most discomfort among the analysts of the picture, for after all, this was a state commission for the Great Hall of the university, so the painting was a matter of public concern. Friedmann, who was one of the most thorough critics around (he regularly attached footnotes to his reviews and included the latest literature on the artists under discussion) and who always expressed himself with tact, now let slip a minor insult, describing Klimt’s style as “hysterical mannerism.”18 Seligmann19 condemned both the thematic concept of the work and its stylistic solution. “The painter should illustrate the puzzle but not himself present it. Trying to make visible what is impossible to research necessarily ends in failure; and what we see is an incomprehensible dreamworld without form, the exact opposite of all true philosophy.” As for the style, he criticizes its “saccharine, nervous and pigeon-breasted elegance, chic and coquetry that lurches into the boundlessly fantastic.”

One day later, the Neue Freie Presse published the counterargument in the form of Franz Servaes’ long and poetic commentary, one of the most sensitive and lyrical descriptions ever written about the painting. Servaes,20 who had moved from Berlin to resettle in Vienna and was an unconditional and unreserved supporter of modern endeavours, had become the art critic for the Neue Freie Presse at the start of the year. (Incidentally he was supported by Hevesi himself.) His ruminative analysis clearly praised the first Faculty Painting as a modern masterpiece of symbolism.21 He too was writing in the wake of Hevesi’s account, but was more dramatic, evocative and precise than him, and less didactic. With neither explanation nor hesitation, he simply writes down what he sees in the picture and all the associations conjured up inside him while looking at the painting, following its rhythm of colours and forms. It is not until the middle of his writing that he reveals he is describing Klimt’s painting, when he wonders whether the “spirit” of the work would be understood in Vienna and Paris. With mounting passion, he probes for comparisons, turning to music for assistance:

The entire work is saturated with music. … Philosophy is here conceived as creator and symbol of the universe … Imagination and passion are poured forth into the cosmos. Klimt has painted that. He dared to venture into the cosmic realm through his imagination. … He no longer paints the philosophers as the representatives of the knowledge they have themselves created. He paints the very object of their research: Life and the Universe. In doing so, perhaps quite unconsciously, he touches on the diversity that still resides in our philosophy. The philosophy that Klimt has painted means the conception of the world as it existed in the age of Darwin, Fechner and Nietzsche. That is what is new in this artistic creation, and also truly modern.

He then turns to the problematic compositional question, much debated by the painting’s detractors, posed by the picture’s intended location. How could a solution so obviously planned in a vertical format fulfil the function of a ceiling painting? In Servaes’ view, a reassuring answer would only be forthcoming when the other Faculty Paintings were ready and the works could be evaluated in the light of their combined effect.

Franz Servaes’ analysis is a prime example of art criticism written as a work in itself, a common practice from the mid-nineteenth century onwards among professional critics as well as writers and poets. (The most famous work in this genre is Walter Pater’s essay on the Mona Lisa.) In this piece, Servaes, who also nursed ambitions as a writer, convincingly unpicked the layers of symbolic meaning in Klimt’s painting, which are so closely interwoven with the solutions of form. The almost immediate emergence of a band of supporters around the painting was largely due to literary essays of this kind, which suggested to viewers, in powerfully persuasive language, that this unusual painting, which broke every conventional allegorical tradition, was a masterpiece. Servaes’ article would not be out of place in an anthology of “empathetic” art criticism from the period, and in this instance Hevesi’s “pupil” surpassed even the lofty heights of his master.

Every reviewer of the painting, whether they liked the work or not, rightly perceived that such an interpretation of philosophy had an underlying pessimism, a profound scepticism that the world could ever be known at all. It was defended unconditionally by those critics who had enthusiastically supported Klimt since the founding of the Secession: Hevesi, Hermann Bahr, Franz Servaes and Richard Muther.22

In connection with Philosophy, Muther wrote,

Klimt is the follower of no one. He did not avail himself of any existing template; instead he created a work out of his own reflections in which the great abstract themes of his time are represented with a nervous and colouristic vitality. The heavens open. Gold and silver stars flicker and the void is spattered with sparkling light. Naked human bodies float by. Green mist accumulates into ghostly forms. A fiercesome head, crowned with laurel leaves, stares out at us with its huge, penetrating eyes. Science plumbs the depths to encounter the sources of truth. Yet the latter remains the ever-inscrutable sphinx.23

At the end of his long piece of writing, however, Muther opined that this mystical and lyrical vision might nonetheless prove unsuitable for decorating the ceiling of the Great Hall.

As we have seen, though Seligmann criticized the large panneau, his tone was far from contemptuous. The critics writing in the Neues Wiener Tagblatt, the Reichspost and the Deutsches Volksblatt, however, were negative in their judgement of the picture. The difference of opinion might not have escalated if the proponents of the Secession, in particular Hermann Bahr, had not pulled out all the stops to deflect every objection with irony, sarcasm and mockery. The feuilleton on the campaign that was published in the Wiener Sonn- und Montagszeitung is decidedly entertaining.24 Seen from the perspective of a visitor to the exhibition who is determined to comply with modern expectations, it follows the events in the form of a diary. If only half of what the “diary” presents is true, then it embarrassingly lays bare all the tactics and strategy used by the Secession in their effort to dominate publicity and thereby public opinion, and to dictate what should be appraised and how. With their highly charged rhetoric, the zealous critics crossed the dividing line between educating the public and inflicting “opinion terrorism” upon them. Hermann Bahr delivered a lecture on Philosophy about which Gottfried Fliedl concluded, “In his speech, which will also be printed and circulated as a sort of manifesto, the defence of Klimt culminates in a fundamental defence of the elite in art and among artists against the ‘mob.’ In this combative script, the arrogance and sense of superiority of the Secession’s ideology finds expression.”25 Bahr referred to Schopenhauer in asserting, “Art has always been on hand, indeed it is its main aim, to express the aesthetic feelings of a minority of noble and sophisticated beings in clearly realized forms. From these the masses will slowly and with effort learn to appreciate what is beautiful and of high quality.”26 Besides Bahr, Hevesi was the most active writer in defence of Philosophy. When it became apparent that some of the university professors deemed the spirit of the painting so unacceptable that they were preparing to lodge an official protest with the minister of culture, the leadership of the Secession launched a pre-emptive strike, assembling before the painting on 27 March and, in a sentimental gesture that was tantamount to a declaration of their faith, laying a laurel wreath bearing the inscription, “Der Zeit ihre Kunst, der Kunst ihre Freiheit” (To the age its art, to art its freedom).27 Hevesi wrote about this, and about the entire scandal that was about to erupt, in the 28 March issue of the Fremden-Blatt.28 The following day, in an article entitled “Für Klimt” (In support of Klimt), he assumed an even more impassioned tone in confronting the uncomprehending conservatives.29 With sarcastic humour he pilloried those university professors (and their contradictory arguments) who dared to express (whether publicly or as private individuals) their displeasure with the painting. One day later, titling his article “Die Bilderstürmer von Wien” (The iconoclasts of Vienna),30 he continued his campaign against the opponents, and also republished the text in the Pester Lloyd. (This time, he included a new version of his analysis of the artistic virtues of Philosophy.)

Thanks to the scandal, crowds of visitors flocked to the Secession during the three weeks of the exhibition, while questions of painting, modernism and art criticism filled columns in the press for months afterwards. The incorruptibly stringent Karl Kraus, who used his one-man journal Die Fackel to expose the absurdities of society and especially the manipulative tactics and fabrications of the daily press, twice cast his opprobrium on the painter and his allies, in March and again in May.31

Since Klimt followed in the footsteps of Makart he attracted attention because he painted Khnopff-like heads which caused some astonishment; when he moved on to Pointillism, a genre that he mastered with honour, we could observe by means of a cunning use of eclecticism the representative of a period of decline in true art in which, in place of individuality, only ever more interesting individuals are highlighted. Younger artists, who often failed to transmit an authentic personality, saw in Klimt the ultimate craftsman, and the more unfinished his products appeared, the more they were inclined to overvalue them.32

In his March pamphlet, Kraus also sarcastically gave a topical political angle to his interpretation of the picture.

From the first moment it was clear to me. The ever-topical Klimt had painted an allegory of the Austrian language problem. Sexes come and go, the young appear full of hope and the oldies proceed forlornly to the grave: meanwhile voices of the people, their unfathomable, unsolved yearnings, lurk in a greenish fog, nurturing their aspirations to master the language puzzle.33

Naturally, Kraus defended the university professors in the name of reason, for they were protesting against the introduction of allegorical works in the Great Hall of their institution.34

In his defence of Philosophy, Hevesi consistently, albeit uncharacteristically vehemently, pleads in favour of stylistic freedom for art (and for artists); he peppers his text with numerous aphoristic turns of phrase (“Künstlerkunst nicht Publikumkunst” [Art for artists, not art for the public]) and goes so far as to define the confrontation in extreme terms (“Kunst oder Nichtkunst ist die Frage” [Art or non-art, that is the question]),35 even though all that was at stake here were differences in taste and differences in aesthetic sensibility, rather than any anti-art sentiment. Hartel, the Minister of Culture and a professor of classics and philology, stood on the side of the Secession and supported the freedom of artistic experimentation. What Hevesi failed to acknowledge here was that the matter at hand was actually about the freedom of critical opinion, and about the conceptual conflict between traditional liberal, bourgeois public opinion and the role of professionalized, elitist modern art criticism. Over the preceding decades he had grown so accustomed to the unquestionability of his professional reputation in Vienna, and he believed so sincerely and devotedly in Klimt’s stylistic experiments (in the exceptionally high artistic standard that the painter embodied, and in the artist’s pursuit of a new, individual synthesis), that not for an instant could he contemplate that anyone could reasonably or justifiably have a different opinion of this style. He railed against all those who failed to understand that Philosophy was an extraordinary masterpiece, an emotion-charged, symbolic manifestation of the modern, pessimistic view of life and the world, transposed into a colourful image. In Hevesi’s view, anyone who lacked the capacity to feel this way was—in this respect—a blinkered, conservative philistine, regardless of how progressive and accomplished they might be in their own field of science.36 Hevesi’s role was to enlighten people, to win them over to the artistic way of seeing things, and he used all his verbal skills in his efforts to help people understand this irrational, questioning, pessimistic yet aesthetically persuasive worldview.37 For the first time in his life, he was met with trenchant resistance from the public, and what is more, from the elite and cultured public who otherwise believed in progress. Initially perhaps, he did not even notice that his role in the public sphere of art was now different from what it had been fifteen or twenty years earlier. There was no longer any possibility of reaching a uniform aesthetic consensus, neither in the now sharply divided art world, nor within the community of art connoisseurs.

Notwithstanding all the individual style variants and the diverse trends that were developing alongside one another, Vienna’s art scene had previously been relatively homogeneous. The works displayed at the annual Jahresausstellung and in the Kunstverein all rested on a more or less uniform concept of art, a common cultural platform. At the same time, the didactic task of the critics, as the representatives of the bourgeois public, consisted of communicating to the artists the expectations of the professional and cultural elite of society, which were rooted in the idealistic tradition stretching back to the Enlightenment; their auxiliary task was to explain the works to the less culturally educated layers of society and to clarify their intellectual and aesthetic messages. This role of the critics, at least until the 1880s, was the norm throughout Europe. Though there was a certain amount of leeway for individual preferences of style and taste, it went without saying that art, on the whole, was expected to fit in with the overarching progressive process of the ethical improvement of society. Even taking into account the Romantic cult of the genius, with its emphasis on individuality, there was no legitimacy in questioning art’s duty to society as a whole to make things better and more beautiful and to support the social utopia which, in this period, also encompassed the ideal of political (and artistic) democracy. (This was still the case even if the wider public primarily meant the more highly cultivated strata of the bourgeoisie.) This fundamental consensus was shaken to the core in Vienna in the 1890s, as manifested most divisively in the press debate surrounding the Faculty Paintings. Now, waving the banner of art for art’s sake, modern, experimental artists attempted to withdraw from this “social contract,” which was still tied to the concepts of the Enlightenment. Instead, artists sought to release themselves from the responsibility of painting works with a didactic, edifying purpose or with a decorative, representative function imposed upon them by state institutions. Rather than sustaining traditions, they opted to make a break with them, and in the name of individualist modernization, they expected the whole of society to accept, with neither question nor restraint, the new art (style, interpretation, artistic solution) that they, the modern artists, were creating for them. This implied that the right to pass judgement on art and on artworks was the sole realm of the modern artists and their allies, and that anybody else was unqualified to comment on this issue.

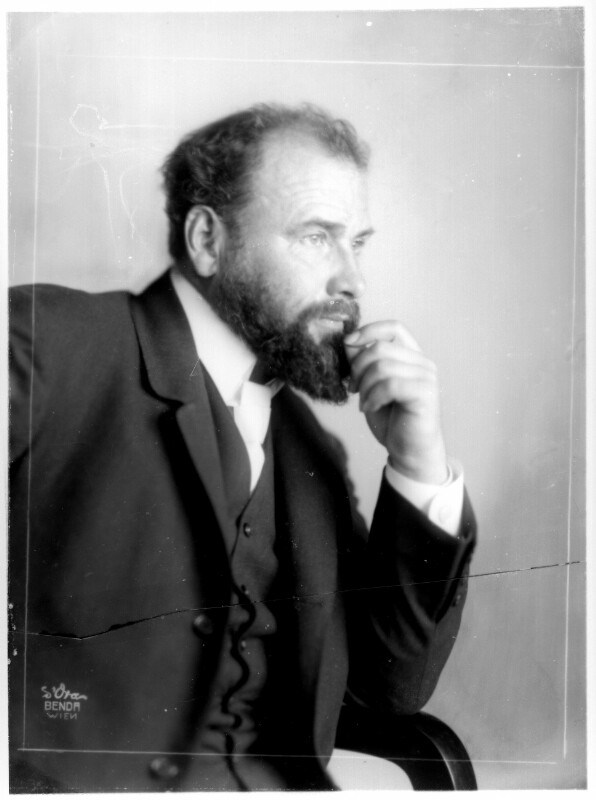

From 1900 onwards, the theorists of the Vienna Secession and the artists with a propensity for formulating theories (Hevesi, Hermann Bahr, and also Carl Moll and Ernst Stöhr) were convinced that they alone could decide which works of modern art were aesthetically beyond dispute. Despite being the main protagonist in the series of cultural political scandals known to contemporaries as the “Klimt affair,” which remained on the boil for four years, Gustav Klimt himself never engaged in theoretical debates. Klimt continued on his path of artistic and stylistic experimentation apparently unconcerned, above the fray, creating a new synthesis to reflect his own worldview. This almost naive resolve and authenticity were what Hevesi so admired in Klimt, and what made the artist the perfect embodiment of the aims of modernity: absolutist and intolerant of all else, fully committed to the creation of something new in art, whatever the cost.

The rebellion against tradition by the modern artists (first and foremost by Klimt) was approached by Carl E. Schorske from the artistic and philosophical angle. Using Freudian terminology in his analysis, he shone a light on the fault line in the worldview at the time, but without emphasizing the other social or sociological aspects of the events surrounding the Faculty Paintings (or indeed the arguments of the opposing side).38 Werner Hofmann concentrated on the philosophical message of the works as strictly applied to the internal artistic world of paintings, likewise without reference to the broader social and economic milieu. Only Robert Jensen, the pioneering researcher of the fin de siècle pan-European art market, placed the Secessionist “rebellion” in its wider social context, highlighting the problems associated with the market for artworks, and underlining that at the very heart of the debates revolving around what were ostensibly purely questions of aesthetics and taste, and despite all the idealist rhetoric, there lay the interests of power and money.39 Jensen, however, focused mainly on the situation in France and Germany and on the role of the secessions there, and only touched upon Vienna in passing.

As the commercialization of the art scene in the Imperial City gained momentum, the relative homogeneity of the exhibition system, supported equally by the state and by society, began to crumble, while the concept of art that rested on the artistic philosophy of the Enlightenment shattered under the influence of the notion of ars gratia artis, making way for all the different art theories of all the different art groups. The critics were also forced to alter their role: due to the function they fulfilled in the press and in the public sphere, they were incessantly obliged to adopt a standpoint among the various competing—and often conflicting—art groups, and they struggled in vain to maintain their own intellectual and moral independence in this battle of interests. It became nigh on impossible to remain neutral and objective.

Hevesi’s emotional and intellectual radicalization is psychologically understandable, but to an extent it is nevertheless a mystery why the tone he used to condemn his uncomprehending and stubborn opponents now became so uncustomarily scathing. Not once did any of the other critics refer to Hevesi by name, nor did they ever accuse him of bias or prejudice (perhaps not wishing to, perhaps not daring?); they merely made allusions. The sharp-eyed Karl Kraus, however, who, like the indignant professors, was no true connoisseur of painting, wrote in Die Fackel about the discrepancies between the intended function and message of the commissioned painting and its “fulfilment”40 in a tone that was similarly schoolmasterly and spiteful: “A philosophical artist may certainly paint philosophy; but he must allegorize it exactly as it appears in the philosophical brains of his age.”41

The most elegant analytical report on the situation is the dignified response to the press campaign that was published in the Sunday 1 April edition of the Neue Freie Presse, the paper with the largest circulation at the time.42 The author of the article was none other than the paper’s long-time columnist Hugo Wittmann,43 who incidentally declared himself a devotee, or at least a sympathizer, of the Secession and the modernists. In respect of the debates that had erupted over Klimt’s painting, he pointed out some substantial artistic and political questions. He felt that the public was being terrorized by the critics: “Du sollst und mußt bewundern!” (You should, indeed you must admire!). With infallible logic, he argues that behind the slogan of “freedom for art!,” what was going on in practice was discrimination by the supporters of the Secession against those with different tastes when it came to matters of style. The starting point for his argument was Hevesi’s own motto on the front of the Secession Building: “Der Zeit ihre Kunst, der Kunst ihre Freiheit” (To the age its art, to art its freedom). But, the author asks, who decides what kind of art is truly desired or considered contemporary by the (present) time? And is obscure symbolism really the contemporary style of the turn of the century?

In this article, there is another direct though nameless allusion to Hevesi and the other rapt critics who accepted the painting without reservation and who wanted to impose this opinion on the public as well. In the interest of individual taste, the author analyses at length the reasons why he dislikes Philosophy. He presents his case with logic and composure, and he credibly explains why, to the rationally minded “average viewer,” raised amid the cultural values of humanist traditions and believing in human progress (and thinking about the world with a similar optimism to that held by the majority of the generation of positivist scholars), the bewildering, disorientating symbolism represented by Philosophy, with its undertones of pessimism, may not appear as a reasonable expression of the present time, which regards itself as progressive, modern and rationalist.44 The problem illustrates how the elite intellectuals working in the state system of institutions and the young intellectuals (especially artists) who worked outside this system had become separated by a chasm in worldview. The young rebels now believed in the irrational view of the world and of humanity, which they felt was a qualitative improvement on what had gone before.

Klimt’s panneau was taken off the wall in April and sent to the Exposition Universelle in Paris, which opened in May. It was exhibited in the Austrian pavilion there, was awarded a Grand Prix by the international jury, and by all accounts, the painting was well received in the Parisian press.45 The painting’s admirers naturally felt vindicated, while its detractors took not the blindest bit of notice. In May, eighty-seven professors from the University of Vienna submitted a petition to Dr. Wilhelm von Hartel, Minister of Education, asking for Philosophy not to be installed on the ceiling of the Great Hall. The petition was ignored by the ministry. Hartel asked his friend, Professor Franz Wickhoff (with whom he had once co-authored a book), to help him persuade the doubters of the merits of the painting. Wickhoff, one of the most respected art historians in Vienna, travelled home from Rome to lend his support to Klimt’s painting, in opposition to his fellow teachers at the university. Wickhoff challenged the idea that the figures in the painting were ugly. On 9 May 1900, he delivered a lecture entitled “What is ugly?” to the Philosophical Society. Though no verbatim record of the lecture survives, the essence of his argument about the substance and relative nature of the artistic, aesthetic notions of beauty and ugliness was printed in the 15 May issue of the Fremden-Blatt. The aim of his lecture was to garner acceptance of modern art (and Klimt’s painting), which intuitively reflects the fundamental questions of the world.46

In the first press debate in March, Karl Kraus did not yet mention Hevesi by name. In May, however, discarding his earlier deference towards Hevesi, he launched a vituperative attack on him in his response to the critic’s most recent writing:

This art critic, who has developed over the last few years from a sharp-witted Feuilletonist into an adviser on confusion for the Secession, and whose style through association with Herr Bahr has become completely degraded, requires a determined resistance… Herr Hevesi produces valuable concessions. I believe he secretly agrees with the suggestions made in the 36th number of Die Fackel: one only needs to change the title from “Philosophie” in order to point the enterprise in another direction. The artist was, after all, only concerned with “creating an interestingly painterly flickering of colour spots.” The “cosmic imagination,” about which Herr Hevesi originally discoursed in his commentary on Klimt’s pictures, has now entirely vanished. That Hevesi was indeed the originator of this conceit is the second valuable admission that he makes in his latest public relations effort and which confirms my suspicion. Of the interpretation of the picture in the catalogue Klimt is guiltless; Herr Hevesi confesses that he wrote it because he felt that the public would stand before the picture and be unable to comprehend it. This is the background to the cosmic slogan devised by journalism, which has befogged all critical brains and has bubbled up around Herr Klimt and his weak artistic product. Because eighty-seven professors have dared to raise their voices against the desecration of their domain, they are treated with patronizing flippancy by the satellite reviewers of the new art as if the latter possessed the wisdom and knowledge to make judgements rather than the beneficiaries of three years gymnasium study. Messrs. Hevesi and Bahr have supplied the tune, the witless youth twitter in their wake.47

As the ministry had failed to respond to the professors’ petition, Kraus continued:

The protesters include men such as Boltzmann, Jagic, Lammasch, Lang and Wiesner, while the twaddle about “reactionaries” is sufficiently reduced to absurdity by the addition of names like Benedikt, Jodl and Sueβ. But Herr Bahr applauds the “brief dismissal and calling to order,” which the Ministry of Education inter alia accorded the opponents of Philosophy, while Herr Hevesi rejoices in those who recently offered judgements delivered in the Art Committee with “all the weight that bespeaks the confidence of competence.” One might ask wherein lies the competence that dismisses as unimportant the protest of eighty-seven professors consisting of senior and in some cases outstanding scholars?

The closing lines of the article react to the Parisian reception, and here Kraus, who also stemmed from an assimilated Jewish family, coined a fearsomely double-edged phrase that was later repeated on countless occasions in condemnations of the style represented by the Secession and especially by Klimt: “The great success of Herr Klimt and the Secession in Paris lies in the fact that the Parisians have derided the imported art [from Vienna] as goût juif (Jewish taste).”48

The heat of summer quelled the tempers of the combatants, and the eminences at the faculty quietly accepted defeat, for now. Klimt, meanwhile, seemingly unaffected by the enduring scandal, continued to work on his next Faculty Painting, Medicine.

Medicine

At the tenth Secession exhibition, held the following spring, Klimt presented his newest, as yet unfinished composition, which caused the debate to flare up once more. Exacerbating the problem was the fact that, published to coincide with the opening of the exhibition, the latest issue of Ver Sacrum, the Secession’s exclusive periodical,49 featured the series of nude drawings that the painter had made in preparation for Medicine. A few indignant moral guardians at the public prosecutor’s office called for the issue to be pulped, and although this was not upheld by the Viennese provincial court, the furore had already re-erupted.

The daily press was filled with polemics, and the exhibition broke all previous records at the Secession, attracting 38,349 visitors.50 Five days after the opening, twenty two members of parliament submitted an interpellation to Hartel concerning the Faculty Paintings, but the minister remained firmly on the side of artistic freedom. He refused to cancel Klimt’s commission

Inevitably, it was Hevesi who published the first review of the exhibition, which appeared in the Fremden-Blatt the day after it opened on March 15.51 Before discussing the painting, he emphasized loudly and clearly that, in terms of imagination, purity of artistic invention, and loyalty to his own true self, Klimt’s artistic greatness was unsurpassed by any modern foreign master. “The greatest modern painters abroad do not excel Klimt in painterly imagination or in the greatness and purity of his artistic sensibility, or in authenticity. This authenticity is what continually drives him forward in his career.” Hevesi admits he nursed anxieties about whether the painter could possibly reconquer the artistic heights that he had reached with Philosophy, but he was now relieved to see that, “in the course of this struggle he ripened into a master.” His praise is conveyed in a reverential tone, and his exultant style attests how sincerely he adored the painting. After a concise and evocative description of the work’s content, the critic discusses how it will fit in with the other Faculty Paintings, and then continues with his analysis of the painterly effects, deploying his customarily powerful and magical language, which was equalled only in the reviews written by Muther, Hofmannsthal and Servaes. Having conjured up an impression of the spectacle, he writes, “And yet everything is no more than vision. As in philosophy it is not something that can be directly grasped, but an individual aestheticizing of the corporeal.” Hevesi concludes by praising the other paintings exhibited by Klimt at the same time, two female portraits and two landscapes, stressing that the master had once again added something new to every genre. With his lengthy and detailed analysis, he sought to convince viewers that with Medicine, Klimt had outstripped even the artistic achievement of Philosophy.

On 20 March, the Pester Lloyd published Hevesi’s article of 18 March in which he reports how the passions surrounding Klimt’s painting already reached boiling point on the day of the vernissage.52 He now wrote with far greater restraint, analysing Medicine in nuanced detail. While this time around he did not state explicitly that the painting was more significant than Philosophy, he deemed its motifs to be richer and its overall effect to be more decorative. (The painting glowed in warm shades of red and orange.) His description here is briefer and more measured than expressed than in the Fremden-Blatt. He relates how the Viennese public was outraged by the naked depiction of the young pregnant woman. For the benefit of his readers in Budapest, he lists a long line of art historical precedents. (The feuilleton also reviewed the other pictures at the exhibition.) The newest round of debates caused deep tremors in Vienna’s artistic life, and indeed in the entire cultural scene, and though it continued for many more weeks, Hevesi contributed no further writings to it.

In the Wiener Zeitung supplement, Armin Friedmann wrote about the picture, albeit briefly, emphasizing that, as it was unfinished, it could not be properly judged, although he also noted the work’s pessimistic tone.53 Friedmann likewise predicted that the intellectual and moral confrontation over Philosophy, which had only just abated, would break out anew and even escalate more intensively than the year before, so he preferred not to take up any position at all.

Three days later, in the Neue Freie Presse, Franz Servaes analysed the painting exhaustively and with utmost care.54 Like Hevesi, he considered Medicine a more successful panneau than Philosophy. He first reviewed the portraits exhibited at the same time, widely admired by other commentators (only two of the portraits were by Klimt, while the rest were by other masters of the Secession), and only afterwards, as though building up the readers’ curiosity, did he turn to Medicine. Out of precaution and by way of explanation, he ponders at length on the long-standing tradition of depicting nudes in allegories to express general notions applicable to the whole of humanity. (This was his way of deflecting the objections, probably already rife by then, to the “unchaste nudity” that could be seen in the Faculty Paintings.) Treating almost every single figure one by one, Servaes strives to enlighten his readers about their meaning, their references, and the inner logic of their artistic solutions. He is at pains to insist, however, that a work of this kind is not merely a visual expression of complex, intellectual content, for “the main thing about this work, as with every true work of art, is that it is born from feeling.” The aesthetic effect that transforms the original concept is the fruit of an instinctive artistic creative process:

This world of forms sways in front of us under a gentle mist that is made suddenly vivid with flashes of colour. A dreamlike mood encompasses it: the eyes of all these naked human beings are closed. They are unconscious partners in their destiny. Neither self-determination nor free will exist in this ethos. Every creature is subject to the force of destiny and it never occurs to them to resist it or acquiesce in it.

It was this passivity, this emphasis on human vulnerability to both fate and death, so brilliantly evoked in the painting, that was rejected by the medical professors, because it challenged the achievements and progress of their science. Seligmann’s profoundly analytical and now harshly critical review55 dwelt on this very notion. At the end of his article, Franz Servaes is in complete agreement with Hevesi: “Klimt’s Medicine is an outstanding, serious and appealing work; compared to Philosophy by the same artist, it represents a marked progress in power and clarity.” With this opinion, however, Hermann Bahr, Bertha Zuckerkandl and the Secession members remained in the minority within Vienna’s elite intellectual circles. The pessimistic symbolic interpretation of science was rejected not only by the older, so-called “conservative” generation of intellectuals, but also by the professors who had been raised on liberalism and positivism, while for completely different reasons it was also dismissed by the other modern-minded and radical circle, Karl Kraus and his followers. An interesting example of the “conservative” view can be found in the lecture delivered to the Wissenschaftlicher Club by Dr. Hugo Ganz, the regular correspondent in Vienna for the Frankfurter Zeitung and the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, who regarded the whole fashion for modernism as reactionary, and not in any sense progressive.56 In his opinion, the decade-long trend of modernism—which declared itself against objective naturalism in the name of unbound individualism, as the sole authentic artistic and intellectual expression of the present time—had humiliated itself. In a sharply hostile tone, but evidently well-informed, he pointed out that “[t]he public’s trust in the reliability of art criticism has been falling for decades. The overall effect is dismaying. A few fanatics of an exclusive sect, who could also be described as buffoons, dandies and simpletons, are the storm troops of Modernism. Trash, known in Vienna as G’schnas [roughly ‘vacuous whimsy’, Tr.] is the end result of their labours.” He barely mentions any names, offering just a couple of positive counterexamples of the kind of art he considered truly great, while stating that Tolstoy’s Resurrection was the most important literary achievement of the decade.

In human terms, it is fully understandable that the professors of the internationally renowned Viennese school of medicine found it unacceptable for the allegory of their science in the Great Hall of the university to depict the triumph of death; that is, the powerlessness of medical science in the face of disease and sickness. Although some of the cultural historical summaries57 retrospectively claim that while medicine in Vienna was outstanding at diagnosis, its position on healing was often one of scepticism. In reality, the school at the time was at the height of its success. It could truly be proud of having furthered developments in healing by enriching medical science with countless innovations, discoveries and surgery methods. At this time the Viennese medical school could no longer be accused of “therapeutic nihilism,” implying that its representatives were interested only in diagnosis and not in healing. For them, the negative interpretation, emphasizing the power of death, must have seemed incredibly cynical. From a human and professional point of view, their outrage was entirely justified: a work with such a worldview should not become the symbol of their vocation.

It was not just the ultra-conservatives who turned against the Secession, against the aggressive and intolerant fashion for the modernist style that they represented, and against their media campaign (which was denounced as an aesthetic dictatorship), but also traditional intellectual bourgeois members of political liberalism, the elite readership of the Wiener Sonn- und Montagszeitung, who had always stood against the anti-liberal, Christian socialist politics embodied by politician Karl Lueger. This circle included a substantial proportion of the assimilated Jewish bourgeoisie as well. Seligmann, who as a painter could genuinely appreciate the technical virtuosity of his peer, Gustav Klimt (and who fully and approvingly acknowledged Klimt’s landscapes), found fault with Medicine. This was primarily because of its deeper, philosophical message—its worldview, as it were. “The entire company of acrobats turns away from her [from Hygeia] and crowds around the grinning skeleton. It is as if the picture were intended to represent not the effectiveness but the helplessness of medicine.”58 While he gives credit to Klimt’s artistic integrity, in that he applied himself seriously to his task, he deems him an insufficiently profound thinker to fulfil such a challenging commission effectively. Consequently, Klimt had managed (unconsciously, in Seligmann’s view, and with unintended cynicism), “to represent philosophy as a pointless dream in the face of unfathomable mysteries, to paint it as an allegory of ‘Medicine’ but also as the ‘Triumph of Death.’”59 With this, Seligmann hit upon the inner, hidden message of the paintings. He could therefore be more nuanced in disentangling the internal workings of the moral outrage felt by the positivist generation of scientists than, for example, Karl Kraus, or the overly hostile critics and viewers (who frowned upon the abundance of nudity and the naturalist manner of painting). While twenty two members of parliament were attacking Medicine and urging the minister to reject the picture, one week later Seligmann returned to the matter and came to Klimt’s defence. He wrote:

It is not hard to see why both the true and false moralists are in the end unsatisfied with Medicine and Philosophy. But the attempt to view the life of the mind entirely in terms of sexuality, or even to elide the two, is a feature of modern art that is as frequently occurring as it is repulsive. I would even say that it has taken and manipulated elements that are not so much neurasthenic as nearly psychopathic.60

Karl Kraus defended the twenty two elected representatives who had condemned Klimt’s state commission in parliament. Sardonically, he wrote:

And if he should happen to discover the slightest sense of the connection between what has been painted and the title of same, “Medicine” among the bodies that throng behind the luxurious saloon lady [that is, Hygeia, I. S.], it will perhaps dawn on him that Herr Klimt, who has spotted that we urgently need a ceiling picture for “Medicine,” has delivered a satirical modification of his ministerial contract to depict the chaos and confusion of terribly diseased bodies to be seen in [Vienna’s] Allgemeines Krankenhaus.61

The literature on Karl Kraus often shies away from discussing his irrepressibly moralizing anti-Secession and anti-Klimt writings. Kraus’s satirical comments tend to be attributed to personal affronts. Pillorying the perceived aberrations in the art scene, however, fitted in well with his moral stance against the corrupt and manipulative “liberal” press, and the publicist’s relative conservatism may have played a part in his habit of attacking, whenever the opportunity arose, the liberal plutocracy and their snobbish taste and lifestyle.62

The Secession as a group adhered so strongly to the belief that the “artist” was entitled to complete freedom and to do whatever he pleased that they ended up raising tensions even further. That spring, they committed an error that ultimately backfired on them, leading to a weakening of the group’s earlier positive social image. Carl Moll, writing in the Neue Freie Presse, and Ernst Stöhr, in the pages of Ver Sacrum, took it upon themselves to castigate sharply the critics who disagreed with them. The conceited tone and aggressive style of the two painters now summoned up the wrath of one of their most important foreign allies, the highly respected professor Richard Muther.63 The German Muther, one of the leading apostles among critics of modern painting,64 always judged the art events in Vienna from an international perspective, that is, more strictly than the locals and Hevesi. Muther recognized that Klimt now ranked among the true greats of contemporary European art (his other examples being Besnard, Klinger, Ludwig von Hoffmann and Toorop!), but he was no fan of the Faculty Paintings. In 1901 he called into question the compositional unity and calm monumentality in Philosophy, and he voiced similar complaints in connection with Medicine. Muther also condemned the Austrian parliament for attempting to interfere in matters of art, but he was enraged by the arrogance in Carl Moll’s writing and especially by the tone of Ernst Stöhr’s article in Ver Sacrum. In Muther’s view, the artists’ pompous aristocratism, with which they rejected all criticism and looked down on laymen, was a sign that the Vienna Secession had lost its sense of proportion and now complacently overestimated the worth of its own achievements. Having been the first to summarize the history of nineteenth-century European painting in three hefty volumes and working at the time on comprehensive books on modern Belgian and French painting, Muther was intimately familiar with the international art scene. He was withering in his assessment of the first three years of the Secession’s artistic output, especially when set against the ambitious expectations. Singling out Klimt’s works as the exception, he considered the others to suffer from “characterless eclecticism achieved through a vulgar coquetry with foreign nations.” One by one, he deals with the works by the Austrian artists at the tenth Secession exhibition, and one by one he tears them to pieces, sparing only Adolf Böhm, for his artistic independence, and Carl Moll, for his quality. His criteria are artistic autonomy, a new and convincing synthesis of forms and styles, and a fresh and authentic visual experience, but he finds no evidence of this anywhere. Naturally his article is very subjective and emotive, but it does not contradict his previous praise and encouragement. In his view, there are two sides to everything: the Secession did indeed bring something new to the stagnating Viennese art scene, but that was not enough. Muther wanted to remind the artists what it was that differentiated the rearguard from the avant-garde.

This brutal criticism was perceived by many as sorely unjust, and it came as a blow not only to the targets of the diatribe, but also to Vienna’s leading Secession-supporting critics, Hermann Bahr among them. Muther was invited a few more times to report in the columns of Die Zeit on exhibitions in Vienna, especially those presenting works by foreign painters, but the bond had been loosened, and it soon snapped completely. In any case, from November the following year, Die Zeit became a daily paper. Its newly appointed art critic was the writer Felix Salten, who, as a member of “Jung Wien” since the early 1890s and a friend of Hermann Bahr and Arthur Schnitzler, was very much an insider.

Muther’s rebuke inspired Seligmann to deal once more with the role of the critic in artistic life and with the unignorable consequences of this role.

Criticism has changed just as art has. Both have become aggressive and polemical. A fundamental shift of attitudes has occurred. Earlier criticism regarded itself as the opinions formed by an educated and cultivated public, but now it identifies with the artists. … This completely changed relationship has resulted in a personal bond being formed between artists and critics. … The critics are now the publicity arm of the artists, they recycle what they hear from the artists in more or less literary guise, organize the whole into an elevated overview, and whereas the artists used to be afraid of them, it is now the public that fears them.65

The explanation for this, incidentally, he sees in the commercialization of art.

According to the principles of national economy that nowadays see cartels and trusts built up in steel or petroleum, so also the same may be observed in art and criticism. A new artistic stream will be founded and led like a shareholding company. Investors will be sought to lure organizational and administrative talent, make a lot of propaganda, and when what the holding company produces achieves a value or in some other way proves to be successful, the market will be tapped, leaflets printed and at the end of the year dividends paid out. Opinions and views on everything concerning the enterprise are the province not of the shareholders but of course only of the directors; they are the source from which advice is on offer at any time, their sole duty being to influence public opinion in favour of the company.

Our Secession, which may be taken as a model for the founding and leadership of this kind of enterprise, has been extraordinarily lucky. Where idealistic concepts are promoted by such adroit businessmen, one would not expect the venture to fail; yet we believe the founders themselves never anticipated the success with which it was indeed crowned. The shares in the company at present stand well above par; exports are as yet meagre, but the domestic market is booming, and whatever is whispered to the press is immediately brought before the public by more or less gifted hacks.

In the latest Klimt row one saw that quite clearly. The literary pioneers of the Secession worked feverishly to convert a recalcitrant public.66

Here Seligmann addressed a taboo that was generally eschewed at the time by art periodicals, by the wider press, and by public opinion in general, either out of naive idealism or out of ignorance. The business-minded organizers operating in the background of the art market, who cleverly exploited the illusions of the mostly idealistic cultural elite, did whatever they could to avoid giving publicity to the economic mechanisms at play in the field of art or to the underlying financial and technical systems. This article by the keen-eyed painter-cum-critic (who was not a member of these circles, nor of the Secession, and who therefore likely observed their successes with a certain degree of jealousy) must therefore have come as an uncomfortable and unwelcome shock to a number of players on the Viennese art scene.

Even among the closest allies of the Secession, there were few who took account of the ruthless financial interests that lay behind the plethora of texts on art, style and artistic freedom. Though money, in the form of the prices fetched by paintings, was sometimes mentioned, it was merely as an incidental fact, a sort of “proof” of the worth and value of an extraordinary masterpiece, emphasizing the sacrifice that a patron or client was willing to make for art. Hitherto, nothing had been written in Vienna about the operations of the art world that dominated and controlled the art market, or about the press that acted in its service. Seligmann observed a certain change in this situation in the furious press debate surrounding Medicine. This was the work that spurred the cultured public (the university professors) into rebellion, and the controversy culminated in the conceited and clumsy attack by the two painters of the Secession. Richard Muther mistakenly took these attacks as a personal insult, prompting the international crusader for modern endeavours to switch from celebrant to maligner of the Vienna Secession. With a soupçon of Schadenfreude, Seligmann noted that this had called the entirety of modern art criticism into question. Later, in 1910, when selecting from his earlier writings for inclusion in an anthology of studies, Seligmann considered this feuilleton so important that it was his only review from the Wiener Sonn- und Montagszeitung to be republished.67

The “final report” on the turmoil surrounding Medicine, a balanced and elucidatory summary of the scandal, was once again published in the Neue Freie Presse, penned as before by Hugo Wittmann.68 After denouncing, with a modicum of irony, the grotesque reactions of the visitors to the exhibition and of the politicians, Wittmann averred that politicians (indeed politics) had no right to demand any sort of state or official art. Moreover, Wittmann said, it should not be the majority who decided who was a great artist (he supported this point with numerous examples from history), although he also condemned the steps taken by the other side. In his view, the critics who opposed the painting had also erred, for by focusing on the political angle, they had stifled the otherwise legitimate complaints about the work’s form and content. He then tackled the criticism of the painting, which he regarded as botched, giving a lengthy and thorough explanation of his reasons.

He was supposed to paint an allegory of healing, and he painted a triumph of death, something like a dance of death. How can you understand that? … Precisely the wonderful achievements of modern healing, for example the terrific advances in painkillers, should have been highlighted. But the artist has simply painted the powerlessness of medicine.

Despite all his personal remonstrances, his artistic objections and his protestations of principle, Wittmann acknowledged Klimt’s prerogative to paint the allegory of medicine as he saw fit, because, he argued, even such geniuses as Michelangelo were known to make mistakes in their works.

It is not for the state to take sides in this matter. It is a quarrel between art and criticism, in which anyone can take part, because judgement is free – as free as art itself. Even a parliamentary representative may make his contribution, naturally as a private individual. The only thing that is not acceptable is for him to call in aid the official weight of the state; he should not try to tamper with the opinions of the majority.

These clear-headed contemporary writings underpin Werner Hofmann’s finding:

The protest of the professors against the Faculty Pictures touches on one of the central conflicts in the humanities in the nineteenth century. In the resistance of the academics to Klimt’s “nebulous thoughts” one sees the clash between the researcher and the visionary, between “knowledge” and “wisdom,” between rationalism and irrationalism. This was the conflict in which Nietzsche spied the beginnings of a new, tragic culture, of which the most salient characteristic is that wisdom displaces knowledge as the most elevated aim. Undeceived by the tempting diversions of the sciences, wisdom turns an undeviating gaze on the whole world scene and tries to replicate its endless suffering with empathy and love as if it were its own experience. This conflict places the artist who nurtures sympathy for this boundless tragedy in the camp of “wisdom.” Progress, the ancient knowledge of something that remains forever the same, counts for nothing in his eyes. This stance impels Klimt’s search for a greater mystical profundity in his repertoire of themes.69

The Secession and its artists, Klimt included, pulled through this first major crisis of their artistic legitimacy, and undeterred they carried on with their preparations for the Beethoven exhibition. This would be the most complete manifesto of their union, conveyed in symbolic language, the ars poetica of their concept of art and of the world, centring on the immortal figure of the composer-artist-genius.

Art criticism in Vienna changed after the controversies of the Faculty Paintings. Hevesi, in particular, must have endured a period of deep crisis; henceforward, he gave up fighting with such vehemence, and refused to “sink” to the level of pointlessly sparring with Karl Kraus. He also had to decide whether to remain faithful to the ideals and worldview of his youth, when he believed that science and progress would create a modern liberal, developing and viable civic society, or to side with the irrational, emotion-driven branch of modernism, which proclaimed a pessimistic view of humanity and which sought to guide the world not with science, but with the help of art. Judging from his writings, he continued his efforts to emphasize the most positive aspects of both, and he unfalteringly supported the experiments of the Secession with all his heart and soul.

Whereas the previous year, Hevesi had published his ironic and combative articles in defence of Philosophy with almost daily regularity, on Medicine, as we have seen, he only wrote a single feuilleton in Vienna, in the Fremden-Blatt. It is as though he had given up on his role as the main “influencer” of art criticism. Hermann Bahr had always been louder than Hevesi, but Hevesi was the éminence grise. Bahr gave a lecture in defence of Medicine in the Concordia, and later, in 1903, he compiled an anthology in which he gathered together all the attacks directed against Klimt.70

Could it be that Hevesi felt that the other side also had a valid point? Whatever the truth, he continued to compose thoughtful articles on the works exhibited elsewhere in Vienna, lending his support to other talented artists. He analysed the exhibits in the Künstlerhaus, the Hagen-Bund, the Galerie Pisko, and the applied art shows, and voiced his enormous appreciation of high-quality works by older artists. He did not renounce his conviction that the future of Viennese art was taking shape in the experiments of the Secession, but he no longer accorded them the sole privilege, no longer saw them as the only chosen ones, not even in Vienna. It was already becoming clear that a younger generation was emerging, even bolder and more radical in their experimentation. It was probably a different task that led to the reduction in his regular output of reviews. In 1901 and 1902 he devoted the bulk of his energy to demonstrating, both scientifically and in a historical context, that the most important contemporary artists and stylistic endeavours in Austrian art were to be found in the Secession, and that the Secession artists were carrying on a long and noble tradition in Austrian/Viennese art. It was at this time that he wrote the first substantial summary of nineteenth-century Austrian art in an effort to prove that the most important painters, who with every passing generation came up with fresh, new approaches and styles, were all the “Secessionists” of their own time.

-

The exhibitions of watercolourists were traditionally held in winter. Their popularity gradually increased, and they were often visited by Emperor Franz Joseph. Large numbers of works were sold at these exhibitions, and foreign artists were also invited to participate. ↩

-

“Die Sezession im Künstlerhause,” Fremden-Blatt, 12 January 1900. Quoted in Ludwig Hevesi, Acht Jahre Sezession: (März 1897–Juni 1905) Kritik, Polemik (Chronik. Wien: C. Konegen, 1906), 212–216. ↩

-

Adalbert Franz Seligmann, “Aus dem Künstlerhause – Ausstellung des Aquarellisten-Clubs,” Wiener Sonn- und Montagszeitung, 15 January 1900. The reader’s letter was signed “Ein Kritiker für Viele,” and it appeared immediately after the reviews. ↩

-

Adalbert Franz Seligmann, “Aus dem Wiener Kunstleben – Ausstellung des Hagen-Bundes im Künstlerhaus,” Wiener Sonn-und Montagszeitung, 19 February 1900. ↩

-

The members of the Hagen-Bund left the Künstlerhaus at the end of the year, on 29 November 1900. Following the example set by the Secession, they campaigned for their own exhibition building as an independent association. ↩

-

Some of the most important analytical summaries are: Hermann Bahr, Secession (Wien: Wiener Verlag, 1900); Werner Hofmann, Gustav Klimt und die Wiener Jahrhundertwende (Salzburg: Verlag Galerie Welz, 1970); Carl E. Schorske, Fin de Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture (New York: Knopf, 1980); Gottfried Fleidl, Gustav Klimt, 1862–1918: The world in female form (Cologne: Benedikt Taschen, 1989); Jeroen Bastiaan van Heerde, Staat und Kunst. Staatliche Kunstförderung 1895–1918 (Vienna: Bohlau Verlag, 1993). ↩

-

The idea of “victimhood” was in fact already present in the narrative of the contemporary press that sided with the Secession, and the later literature built on this. ↩

-

The vast majority of the art historical and cultural historical literature on Klimt’s life’s work tends to focus on the erotic element in his entire oeuvre. In Klimt’s case, there may be some justification in this, because before him, at least in Vienna and in Central Europe, no other painter had been so powerfully defined by portrayals of sensuality and sexuality. Among Klimt’s contemporary European stylistic innovators, it was only in the lives and works of Edvard Munch and Auguste Rodin that these themes played a similarly decisive role, becoming leitmotifs in their art a good decade earlier. ↩

-

See Schorske, Fin de Siècle Vienna, 208–278; 186–248. ↩

-

Hofmann, Gustav Klimt. ↩

-

As such, Hofmann accorded these works a universal meaning. ↩

-

The inscription of Nuda Veritas: “Kannst Du nicht allen gefallen durch deine That und dein Kunstwerk - mach es wenigen recht. Vielen gefallen ist schlimm.” (Schiller: “If you cannot please all with your actions and art, try to please the few; pleasing the many is no good.”) ↩

-

In the last thirty years, the critics of the pictures have always been tarred with the same brush, branding them in general as rigidly conservative and liberal. The literature tends to quote those sentences that were gathered together and published by Bahr in his volume entitled Gegen Klimt, which are often taken out of context for maximum dramatic effect. Hermann Bahr, Gegen Klimt: Historisches, Philosophie, Medizin, Goldfische, Fries (Wien: Eisenstein & Co., 1903). Nebehay’s first collection of critical quotations, while much broader than Bahr’s, is likewise a compilation of uncontextualized excerpts, and what is more, it does not cite the sources precisely. Nevertheless, this has become an essential resource to researchers, as Nebehay also managed to include oral sources. See: Christian Nebehay, Gustav Klimt: Dokumentation (Wien: Galerie Christian M. Nebehay, 1969). ↩

-

Hevesi, Acht Jahre Sezession, 232–238. ↩

-

Hevesi, Acht Jahre Sezession, 233. ↩

-

Hevesi, Acht Jahre Sezession, 234. ↩

-

Armin Friedmann, “Bildende Kunst – VII. Kunst-Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Oesterreichs, I,” Wiener Abendpost, Beilage der Wiener Zeitung, 12 March, 1900. ↩

-

Armin Friedmann, “Bildende Kunst – VII. Kunst-Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Oesterreichs, I,” Wiener Abendpost, Beilage der Wiener Zeitung, 12 March, 1900. ↩

-

Adalbert Franz Seligmann, “Aus der Wiener Kunstleben – Frühjahrsausstellung der Secession, II,” Wiener Sonn-und Montagszeitung, 19 March 1900. ↩

-

Franz Servaes, “Secession – Eine Porträtgalerie – Gustav Klimt,” Neue Freie Press, 19 March 1901. Franz von Servaes (1862–1947) was a German journalist, critic and writer. He graduated in German studies and art history, and from 1888 he worked for the German periodicals Gegenwart and Nation. In 1899 he moved to Vienna, working as an art critic for Neue Freie Press, and after Theodor Herzl, he took over as the feuilleton editor. In 1902 he wrote a book on Segantini, a commission he received thanks to Hevesi. ↩

-

Franz Servaes, “Secession – Gustav Klimt und andere Jung-Wiener,” Neue Freie Press, 13 March, 1900. ↩

-

In these years Muther regularly wrote reviews for the Vienna weekly Die Zeit, and in 1900 his articles were collected into a volume entitled Studien und Kritiken, Bd. I, published by Wiener Verlag. ↩

-

Richard Muther, Studien und Kritiken (Vienna: Wiener Verlag, 1901), 57–58. ↩

-

“Aus dem Tagebuche eines Zeitgenossen – Unpolitisches über die ‘Philosophie,’” Wiener Sonn- und Montagszeitung, 9 April 1900. The signature, W, probably conceals Hugo Wittmann, an old friend of Ludwig Speidel and a well-known writer of feuilletons. Wittmann often published theatre and music reviews in the same paper, and he was not averse to irony and humour. The article was clearly written by a professional, well-practised hand. ↩

-

Fliedl, Gustav Klimt, 65. ↩

-

Bahr, Secession, 10. ↩

-

As is well known, the motto above the entrance to the exhibition building was coined by Hevesi. ↩

-

Hevesi, Acht Jahre Sezession, 243–245. ↩

-

Hevesi, Acht Jahre Sezession, 245–250. ↩

-

Hevesi, Acht Jahre Sezession, 250–254. ↩

-

Die Fackel, no. 36 (March 1900): 16–19; Die Fackel, no. 41 (May 1900): 18–22. ↩

-

Die Fackel, no. 36 (March 1900): 16. ↩

-

Die Fackel, no. 36 (March 1900): 17. ↩

-

Die Fackel, no. 41 (May 1900): 18. ↩

-

Hevesi, Acht Jahre Sezession, 253. ↩

-

Among the professors who deemed the worldview conveyed by Philosophy to be unacceptable were many of the most prominent members of the scientific community at the time, such as Ludwig Boltzmann, Friedrich Jodl and Heinrich Gomperz. ↩

-

Hevesi was brought up in the worldview of Enlightenment, progress, and an optimistic belief in development, and having wholeheartedly embraced these values, he worked all his life to improve the world. The revolution in art brought about by the Secession turned these values on their head and rejected Hevesi’s entire spiritual and philosophical heritage, so for him now to accept these changes as progress marks a sharp contradiction in his attitude. He himself, quite strangely, did not perceive (or was unwilling to acknowledge?) this almost irreconcilable contradiction. ↩

-

Schorske, Fin de Siècle Vienna, 208–278; Schorske, Thinking with History: Explorations in the Passage to Modernism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998), 186–248. ↩

-

Robert Jensen, Marketing Modernism in Fin-de-Siècle Europe (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1994), 182–187. ↩

-

Karl Kraus, Die Fackel, no. 36 (March 1900): 9–12. ↩

-

Karl Kraus, Die Fackel, no. 36 (March 1900): 9–12. ↩

-

Hugo Wittman, “Der Kampf um die Philosophie,” Neue Freie Presse, 1 April1900. Hugo Wittmann, writer, publicist, colleague of Theodor Herzl, and co-author of several theatre plays, though not personally attached to any group, knew the Viennese art scene “from within.” ↩

-

Wittman, “Der Kampf um die Philosophie,” Neue Freie Presse, 1 April 1900. ↩

-

This article was omitted from the critical anthology compiled by Hermann Bahr, Gegen Klimt. ↩

-

Meier-Graefe, who in the next decade would become the great founder of the art canon, wrote a volume in German summarizing the Art shows at the Paris exhibition, which was published that year in both Paris and Leipzig. In his summary, he was very brief in his descriptions of the impressive quantity of paintings on show, devoting just half a page to the Austrians, in which he mentioned three paintings by Klimt. At that time, he considered the Portrait of Sonja Knips to be the best. See Alfred Julius Meier-Graefe, Die Weltausstellung in Paris 1900: mit zahlreichen photographischen Aufnahmen, farbigen Kunstbeilagen und Plänen (Paris; Leipzig: F. Krüger, 1900), 92. There is no published research so far specifically dealing with the Parisian press reception of the Austrian artists. ↩

-

For details on Wickhoff’s arguments, see: Edwin Lachnit, Die Wiener Schule der Kunstgeschichte und die Kunst ihrer Zeit: Zum Verhältnis von Methode und Forschungsgegenstand am Beginn der Moderne (Vienna: Böhlau, 2005), 40–47. ↩

-

Hevesi, Acht Jahre Sezession, 261–264. ↩

-

Karl Kraus, Die Fackel, no. 41 (May 1900): 12–14. Kraus unfortunately did not state from whom or from where he quoted the French reviews, but later he himself frequently referred to the style of both the Secession and the Wiener Werkstätte as “goût juif” (“Jewish taste”). His only basis for this was the fact that the most outstanding works (such as Klimt’s portraits, or the furnishings and jewellery of the Wiener Werkstätte) were only affordable to the plutocracy (bankers and industrial magnates), the majority of whose members belonged to the assimilated Jewish bourgeoisie in Vienna. This accounts for why so many Klimt paintings have left Austria in the last two decades through claims for restitution. The hugely influential moralist and publicist Karl Kraus was a gifted writer, greatly esteemed in literary and cultural history. The rival whom Kraus despised most vehemently in Vienna was the writer, critic and author of feuilletons Hermann Bahr, who later compiled a volume of articles written against Klimt, published in 1903. Notably, Kraus’s articles in Die Fackel were all omitted from Bahr’s selection. Bahr, Gegen Klimt. ↩

-