Towards Transformative Propaganda A History of Student Activism at the Australian National University (2020)

In his 2019 study Propaganda Art in the 21st Century, Dutch artist Jonas Staal engages with a question that has been at the heart of progressive artistic research since the turn of the century: what type of artistic production might help us imagine and articulate political alternatives in our era of planetary crisis?1 Seeking to provide an answer, Staal examines the concept of propaganda art, and he challenges the stereotype of propaganda art as being little more than a product of dictatorship. By tracking the evolution of this genre under different modern political systems, Staal demonstrates that “the notion of propaganda art has itself been subjected to propaganda,” and that this has given rise to a belief that any such art could only be “one dimensional, totalitarian.”2 Yet for Staal, propaganda is best defined as “the performance of power,” representing a process through which infrastructures of power shape our understanding of reality, from the “micro-performative scale of a citizen, to the macro-performative scale of a government.”3 This definition demythologises the idea that liberal and capitalist democracies are “beyond propaganda,” or that this form of production “belongs exclusively to a totalitarian past.”4 Instead, Staal heralds propaganda as a strategy “aimed not only at communicating a message, but constructing reality itself” according to the interests of specific power structures, irrespective of their political orientation.5

Seeking to demonstrate that propaganda is not a dirty word, Staal highlights the fact that all systems of power—both established and emerging—draw on its potential to shape consciousness. In making this point, Staal’s approach is reminiscent of the work of philosopher Louis Althusser who, in his famous 1970 essay “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses,” rejected the habitual use of ideology as a term of political abuse, by which “the accusation of being in ideology only applies to others, never to oneself.”6 For Althusser, the notion of ideology could not be reduced to a mere synonym of dogma or doctrine, because in fact every society operated within some form of internalised ideological framework—“a schematic grid through which individuals order, conceptualize, comprehend, and comment upon a world.”7 In a similar manner, propaganda for Staal is not reserved solely for “the other side.” One the one hand, Staal’s study thus captures a philosophical tradition that has sought to draw the curtain over the structure of power—criticising simplistic dichotomies of us and them, good and evil, democratic or illiberal—to reveal principles common to any system of power. At the same time, it reflects renewed efforts by artists, critics, and art historians to rescue the meaning of certain critical concepts from “the dustbin of history,” and imbue them with new activist potential. The term “utopia” stands as a common reference point here: instead of serving to denote something impossible or impractical, this term is used in contemporary progressive artistic practice to recall our collective ability to imagine and actualise alternative social structures and future possibilities. Equally, terms such as “socialist” or “post-socialist” re-emerge in artistic discourse not as a nostalgia for political experiments of the past, but as a principle for the future that preferences solidarity over competition, internationalism over globalisation, emancipation and equality over expansion, extraction, and exploitation.8 By moving away from a reductionist application of these terms and restoring the full complexity of their meaning, progressive artists and critics have sought to counter a discourse that, despite current emergencies, continues to reinforce the status quo.

In the context of art historical scholarship, Staal’s approach sits squarely within an academic tradition that has questioned the frequent equation of propaganda art with totalitarian art, by which both are deemed retrograde and of low aesthetic value.9 Discussions on modern art in particular tend to carefully delineate the use of propaganda as an explanatory tool, conscious that this concept has never enjoyed a straightforward application.10 Staal’s study, however, goes further than recognising the complex meaning of propaganda in calling for a revival of its activist potential, arguing that “today the art of propaganda is of more importance than ever.”11 As we are faced with a seemingly permanent war on terror, rising ultranationalist and alt-right regimes, ongoing refugee crises, structural racism, gender violence and inequity, deepening precarity, and climate emergency, there is an urgency to understand how ruling elites shape our world according to their interests through propaganda. Equally, by expanding traditional propaganda models to include emerging forms of power, Staal opens an avenue for thinking about how propaganda can be used for emancipatory purposes.12 In calling for this renewed attention to propaganda art as a force of “democratization, mobilization, and transformation,” Staal adds this genre to the repertoire of contemporary activist art or “artivisim”—a phenomenon that has been described as the twenty-first century’s first new art form.13

In thinking about propaganda art—whether in historical or contemporary contexts—it is common to train our focus on works of monumental art. Indeed, large-scale public artworks have traditionally served to encapsulate a dominant ideology, and propagate a set of values or ideals that underpin a specific (and often monolithic) worldview. Public monuments that punctuate and orient the layouts of our cities are, therefore, no political innocents: they represent dominant groups and their histories, often to the exclusion of all others. In many ways, this explains why these urban markers have been so central to contemporary protest culture all over the world. It is also why monuments have become a key feature of contemporary artivism, as progressive artistic practice has become intertwined with protest movements over the past two decades. Here, the focus has been predominantly on aesthetic and activist engagement with existing monuments and sites of symbolic significance through which artists transformed, appropriated or occupied existing structures to reveal or change their meaning.14 Staal’s analysis, however, extends beyond the familiar focus on forms of propaganda developed by established political elites, and asks what the propaganda art of emerging power structures based on collectivist principles might look like.

Taking up Staal’s challenge, this article examines the latest addition to the collection of public artworks located around the campus of the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra. Conceptualised and executed in 2020 by ANU students and alumni, this piece—entitled A History of Student Activism at the Australian National University—commemorates student activism on this campus. In situating an analysis of this artwork within a global context, this examination opens with a discussion on the intersection between art and (student) activism, and offers a range of different models for artistic engagement with public monuments arising out of contemporary protest movements. These are presented as belonging to one of three categories: counter-monuments, or structures erected separately from (but in response to) an existing monument or urban marker; anti-monuments, which result from the temporary occupation or alteration of an existing structure; and a-monuments, being the empty space left after a monument has been removed. This taxonomy provides a launchpad for thinking not just about whether efforts to alter existing monuments are effective in challenging prevailing power structures, but indeed—and in answer to Staal’s call—what monumental art capable of capturing a progressive ethos might look like. As a public artwork dedicated to collective emancipatory action, A History of Student Activism offers a valuable reference point in the debate on transformative propaganda art for our times.

A History of Student Activism at the Australian National University

Launched in late March 2021, A History of Student Activism at the Australian National University is a large-scale wall-mounted installation examining six decades of student activism at ANU. As its title suggests, the work showcases a range of protests and interventions, from the march on the South African embassy to call for an end of apartheid in 1960, through to the 2020 campaign against the use of Proctorio software for exam invigilation due to privacy concerns. Created by ANU alumni Esther Carlin, Joanne Leong, and Aidan Hartshorn—who were brought together by Alex Martinis Roe, then Head of Sculpture at ANU School of Art and Design and curator of the project—the installation is a first-time collaboration between these artists on a piece of public art. A History of Student Activism represents the culmination of a string of earlier student-led research projects, including the production of the seventh issue of the progressive Demos journal, which was edited by Vanamali Hermans and Mia Stone, designed by Leong, and accompanied by an audio-visual installation by Carlin and Amelia Filmer-Sankey.15 The seventh issue of Demos, published in February 2018, was dedicated to the history of student activism at ANU, and included a large, fold-out poster of the ‘ANU Activism Timeline’ with information gathered by Hermans and Stone about critical moments in the university’s activist history.16 This meticulously researched and tightly packed timeline would become both the conceptual and formal core of the History of Student Activism installation.

Extending across the white background of the wall, the timeline is constructed around decades, beginning with the 1960s and running through to the 2010s. In translating the printed timeline into a spatial structure, Leong sets out the key events in a series of geometric tiles, which hover around the bold black decadal markers, and spill into adjacent spaces as decades merge into each other. Drawing on her practice of employing design strategies to communicate knowledge, Leong makes the timeline visually readable by using colours and shapes to group key themes—blue for university matters; green for environmental issues; red for activities associated with the Indigenous rights movement—while photographs from each period augment the overall visual impact. With the 1960s and ’70s still regarded as a period of particularly intense political activism in Australia, the installation timeline guides the viewer across some of the major global events of this period, and the responses by ANU student activists to them. These include the anti-apartheid movement, student campaigns against Australia’s participation in the military intervention in Vietnam, and campaigns for Indigenous rights. Subsequent decades are dominated by student-centred issues, including student representation in decision-making processes, the question of housing and food affordability, inclusive curricula and pedagogy, and efforts to address systemic inequities within the educational system. Strong interest in Australian and global social issues continues to inform student activism, with tiles covering ongoing student support for Indigenous rights, gender and marriage equality, refugee rights, and environmental issues.

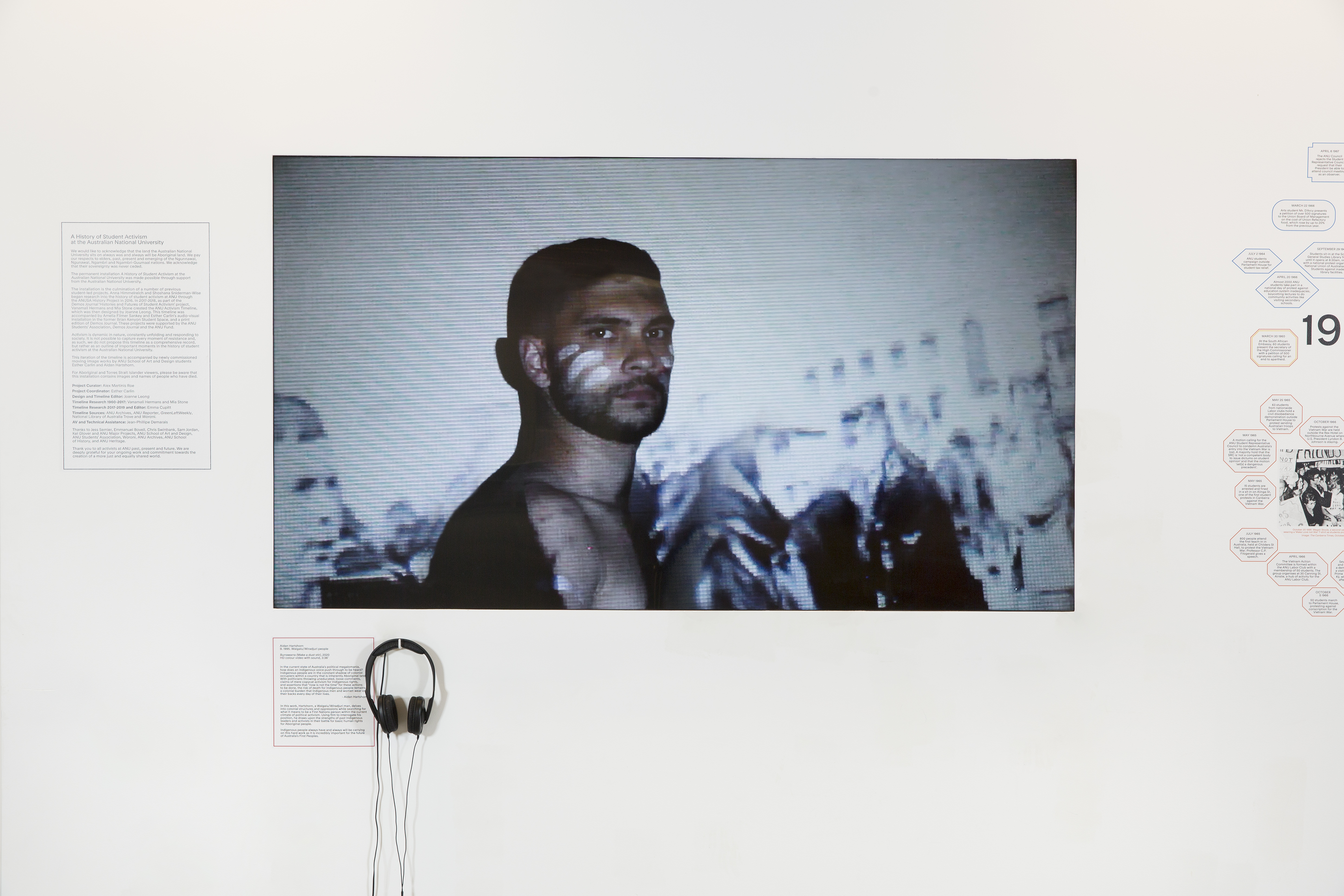

Complementing this central timeline, two moving-image artworks complete the work: Burrawarra—Make a dust stir (2020) by Walgalu/Wiradjuri artist Aidan Hartshorn, and Esther Carlin’s piece Critical Mass: The Establishment of Women’s Studies at the Australian National University (2020). Both video pieces, these works bookend the timeline by highlighting a pair of themes that were formative in the evolution of student activism. Hartshorn’s work acknowledges the struggle of past Indigenous activists, and is offered as a statement about the experience of First Nations people within the current political climate. Carlin examines the student-led establishment of Women’s Studies at ANU, which remains the only academic program at the university to have been founded as a direct result of student activism. Hartshorn’s piece is a self-portrait, examined through frames that alternate between profile and front-on views, perhaps in a nod to police mugshots. Throughout the duration of the piece, footage of police brutality at the site of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in 1972 is projected onto the artist’s face. Established as a protest occupation site opposite Old Parliament House in Canberra in response to the government’s approach to Indigenous Australian land rights, the Aboriginal Tent Embassy remains a powerful symbol of resistance—and one that has inspired generations of activist artists in the country.17 In evoking this imagery, Hartshorn creates a living archive of struggles for recognition that have lost none of their intensity. Carlin’s video demonstrates an equally strong archival orientation, comprising interviews with activists who were involved in establishing Women’s Studies at ANU—Ann Curthoys, Christine Feron, Susan Magarey, Liz O’Brien, and Julia Ryan. These interviews are combined with footage from a personal archive of ANU campus and Canberra from the 1960s and 1970s, which evoke the interplay between the personal and the political that is embedded in the history of feminist movements. Carlin’s work here captures her interest in feminism, and expands upon the practice within Australian art of employing historical and archival strategies to examine feminist politics.18 The two video works create points of focus, which draw out from the central timeline political entanglements that ANU student activists have grappled with across generations.

The artwork’s on-campus location plays a vital role in emphasising the sense of continuity that is foregrounded through the installation’s timeline format. Occupying the light and airy ground floor of the Marie Reay Teaching Centre, the work is a central feature of what is a newly-constructed, multi-use, six-floor building erected as part of the development of the newest precinct on campus, and named after the renowned Australian anthropologist who enjoyed some thirty years of tenure at ANU. The redevelopment of this site, however, involved the erasure of spaces that had once been at the epicentre of student activism on campus—including the ANU Student Union buildings, which were demolished between 2017 and 2018. During the redevelopment, the ANU community raised concerns about preserving the history of the site. Through discussions with the university and the developer, the commissioning of a public artwork dedicated to the social history of the campus would become part of the redevelopment project. The fact that the ANU community ensured that the design and execution of this commission would be entrusted to the student body—along with its location at the entrance of a building designed equally for student academic and leisure activities—allows the piece to successfully link past, present, and future campus life. In transcribing the social history of ANU onto its public infrastructure, the artwork captures a continuum of student experience that is by its nature ephemeral and often understood as specific to each generation of graduates.

Occupying a spacious and light entrance area, the artwork is surrounded by large tables that are often populated with students and campus visitors. This animated yet peaceful atmosphere, however, stands in sharp contrast to the political reality in which the piece was created. Completed in 2020, the artwork came into being in circumstances that are commonly described as unprecedented.19 For Australians, the beginning of 2020 was marked by the culmination of one of the most devastating bushfire seasons in history—an event that further emphasised the fact that we are in the midst of a global climate crisis—followed quickly by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.20 These events also highlighted deep social inequities, drawing a line of demarcation between those who could weather the crisis and those forced to bear the brunt of it, and in the process revealed the decline of emancipatory politics worldwide. The pandemic and its politics have served as a dramatic backdrop to global Black Lives Matter protests that reached a climax in 2020—being, perhaps, the most vocal demonstrations since those mobilised in response to the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. As part of this wave of activism, public sites and monuments have frequently become beacons for discussion about the type of values contemporary societies affirm through urban development. Against this turbulent background, the ANU installation made a forceful debut. Dedicated to a memory of collective emancipatory action, the work took shape amid intensifying debate about public monuments, the type of histories they capture and commemorate, and the values that are reproduced through our heritage landscape.

Monument and its discontents

We are today, as poet Joshua Clover has put it, living in a new era of uprisings.21 Writing in 2016, he noted “riots are coming, they are already here, more are on the way.”22 From the Coloured Revolutions and the Arab Spring to the Indignados, Occupy Wall Street, Women’s March, Black Lives Matter, Gilets Jaunes, and Extinction Rebellion movements, a pervasive sense of frustration with political and economic power structures has manifested itself in a string of protests, many of which have spilled out onto the streets of the world’s major cities. Within this charged environment, public monuments have often come to serve as both catalysts for and targets of public discontent. It was the “Rhodes Must Fall” campaign in 2015 that brought focus to a broader debate about the role of public monuments and heritage sites within contemporary protest culture. Stemming from the University of Cape Town (UCT), this campaign was triggered by student demand for the removal of a statue of mining magnate and politician Cecil John Rhodes—the benefactor of the land on which the university is built.23 The presence of a towering bronze statue glorifying the colonial ruler who carried out a campaign of exploitation, discrimination, and violence against black Indigenous people was seen by the protestors as “symptomatic of the lack of transformative actions being taken by the institution” to address the legacy of this politics.24

According to Brenda Schmahmann, Rhodes’s statute was “a constant reminder for many black students of the position in society that black people have occupied due to hundreds of years of apartheid, racism, oppression and colonialism.”25 On 9 March 2015, UCT student Chumani Maxwele would command the world’s attention by tossing a bucket of human excrement at the sculpture—an act that, as one commentator observed, was reminiscent of protests in black townships that sought to draw attention to the lack of proper sanitation infrastructure.26 The campaign to remove the statue—and through this act compel the university to commit to racial equality, including by decolonising the built environment—involved a suite of protest activities: from performances and debates held on the site, to modification of the sculpture through graffiti, banners, paint, and wrappers made from black rubbish bags, and ultimately the occupation of university administrative buildings and decision-making sites. By April, the UCT Senate decided to permanently remove the sculpture of Cecil Rhodes from the campus grounds.

The “Rhodes Must Fall” campaign subsequently extended to other campuses in South Africa, before spreading across cities worldwide and gaining momentum through social media platforms.27 Having been initially driven by student activism, this now global socio-political movement was characterised by “spatial practices of occupying, modifying and pulling down monuments in public space,” in an effort to counter the influence of monuments that embodied and propagated a value system deemed incompatible with contemporary demands for change.28 “Rhodes Must Fall” engendered another twenty-first-century “ism,” as the movement came to be referred to as “fallism,” with protestors referring to themselves as “fallists,” and promoting their activities through Twitter hashtags #Fallism and #MustFall. The label soon expanded to capture other student demands—#FeesMustFall was used to protest against rising student fees, while #PatriarchyMustFall sought to raise issues associated with gender inequity, exposing the rapid erosion of advancement that had been achieved in this domain in previous decades.

These new labels notwithstanding, the use of monuments as a catalyst for political intervention has a long historical tradition. As Sybille Frank and Mirjana Ristic note in their study of the “fallist” movements, the destruction of monuments has always been an arrow in the activist quiver, with forms of iconoclasm that include the elimination of physical landmarks a universally recognisable expression of opposition to political authority or ideology.29 The act of iconoclasm here, as one commentator has observed, operates not as one of mindless destruction, but as a “sophisticated semiotic process.”30 The stand-out feature in the context of twenty-first-century public protests has been the intensity with which monuments became focal points for public expressions of discontent. The focus on monuments within contemporary protest cultures thus opens a path to think about how modifying, occupying, and removing a piece of public art from an urban location operates as a means of political struggle, and a form of political engagement. It also invites consideration of how contemporary activist art has absorbed this tension between public art and protest to inform its own creative response.

Counter-, anti-, and a-monuments

Forms of artistic engagement with monuments have been rich and varied in the past decade, with some of the most powerful being those that seek to modify the appearance, and by extension the meaning, of individual works or sites. Consider Maurizio Cattelan’s (in)famous sculpture L.O.V.E.—a 36-foot-tall rendition of a human hand making a vulgar gesture in front of the Milan stock exchange.31 Unveiled in 2010, its title is an acronym of the Italian words for freedom, hate, revenge, and eternity (libertà, odio, vendetta, and eternità), although locals refer to it simply as ‘the finger’ (il dito).32 Cattelan’s sculpture is made from Carrara marble, a material of choice among Italy’s renowned Renaissance masters, and his meticulous rendering of skin texture and veins further echoes that epoch’s penchant for naturalism. In a nod to the ruinous state of many antique and Renaissance artworks that occupy our museums, the hand’s digits appear to have been lost over time—save for the middle finger, which makes for the universally recognisable gesture of derision. This loss of lateral digits transforms the hand’s gesture from the so-called Roman salute, used during the fascist years, into a middle finger pointed at the stock exchange, which is itself housed in a fascist-era building. Though originally intended as a temporary installation, the statue remains in place following a successful public petition; the humour and playfulness common to Cattelan’s work does nothing to detract from a stinging critique of political structures that pushed the country into financial ruin.

While Cattelan’s piece was envisioned as a type of counter-monument, a structure juxtaposed against an existing urban marker to question or challenge its meaning, elsewhere (temporary) occupations of public monuments have become a powerful strategy for political and creative expression. This form of intervention has certainly been prevalent within political environments where efforts to vocalise opposition have been systematically marginalised or supressed. In Russia, for example, the past decade has seen an emergence of a vast archipelago of artists and art collectives whose acts of creative occupation have attracted significant attention.33 The work of Pussy Riot, whose practice drew precisely on their ability to organise spectacular and rapid occupations of urban sites with great symbolic significance, stands as a paradigmatic example of this practice. For their most audacious intervention, the group’s target was nothing less than the Moscow Cathedral of Christ the Saviour.34 Dressed in their trademark outfits with florescent balaclavas, on 21 February 2012 the group’s members—Mariia Alekhina, Ekaterina Samutsevich, and Nadezhda Tolokonnikova—walked onto a section in the area of sanctuary reserved for the clergy and commenced dancing and singing their punk prayer titled Mother of God, Chase Putin Away! With presidential elections looming and Vladimir Putin certain to win his third presidential term, Pussy Riot’s performance had been designed to upset the decorum of the Cathedral and draw attention to the relationship between Orthodox Church officialdom and the ruling regime, which was increasingly using spaces of spirituality as a stage for its political campaigning. Expressly defined by the group as a form of political art, this work triggered controversy, generated a global response, and ultimately revealed just how powerful the intersection between monuments and (artistic) activism can be. Indeed, this brief, ephemeral act would evolve into a type of anti-monument, antithetical to the occupied structure in both form and content, but equal in its symbolic power.

The death of 46-year-old black man George Floyd during police arrest in Minneapolis on 25 May 2020 has, among other things, brought this interplay between public monuments and protest into sharper focus.35 Having been recorded by a witness, the brutal treatment by the police and the horror of Floyd’s last moments would cause worldwide shock and anger, galvanising protests against police violence and systemic racism across American cities. These protests unfolded within the charged atmosphere of the COVID-19 pandemic, which in the United States as elsewhere had a particularly devastating effect on minority and underprivileged groups.36 Widespread anger would be channelled against public monuments that had once been erected to commemorate and celebrate political actors whose actions had ultimately contributed to contemporary inequities. From Richmond to St Paul, Boston to Miami, statues of Christopher Columbus were toppled or damaged; Confederate statues across the United Sates also became prime targets. The statue of Robert E. Lee, the Confederate general, which towers over the Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia received a makeover with an image of George Floyd projected on the base along with a Black Lives Matter symbol. The wave of fallism quickly spread worldwide as controversial statues were dismantled: from the removal of statues of King Leopold II in Belgium, whose forces are responsible for deaths of millions following the seizure of Congo in the late nineteenth century, to the spectacular public removal of a statue of seventeenth-century slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol, which was pulled to the ground by rope-carrying protesters, before being dragged through the streets and thrown into the harbour, leaving behind an empty pedestal as the sculpture’s negative or ready-made a-monument.37 In Australia, too, various sympathetic protests would renew the push to take down monuments considered offensive to Indigenous Australians, with statues of James Cook being prime targets.38 Australia’s response is also captured in A History of Student Activism, with student participation in a Black Lives Matter protest in Canberra and a campaign to remove a statue of Winston Churchill from the campus featured in tiles that close out the central timeline.

These creative interventions have all highlighted the various ways in which contemporary urban environments continue to express values of political elites that shape our reality. To return to Staal’s analysis, in recognising the continued existence of (state) propaganda art, the aim is not to equate democracies with dictatorships, but rather to highlight the fact that so-called democratic propaganda was historically far from innocent. In re-examining the critical interplay between politics and art, Staal insists that together political power (or infrastructure) and artistic imagination (which provides a narrative to support it) are the cornerstones of any reality—a dynamic whose relevance cannot be denied by sealing the notions of propaganda and propaganda art “in a time capsule labelled ‘totalitarianism.’”39 Staal’s analysis, however, goes beyond efforts to reveal the ways in which monopolised forms of elite power today deploy artistic production (from public monuments to video games) to protect their interests: the challenge he poses is to identify forms of transformative propaganda that can create conditions for the construction of a different reality. How can alternative forms of power use propaganda art to help a new emancipatory value system—a system that embodies a plurality of views, and allows for coexistence of multiple narratives of the past, present, and future—to take hold? This is a propaganda art model for which, as Staal rightly notes, “the full potential remains largely unknown today.”40

Monuments to activism, or activist monuments

The modification, occupation, and removal of public monuments as a component of contemporary protest raises a critical question: beyond counter- or anti-monuments, or empty pedestals, how should we reimagine a more heterogeneous memorial landscape, which acknowledges the legacies of diverse communities? More poignantly, perhaps, what would a public monument to collective action in the name of transformative politics look like? Here, perhaps, historical experience provides a useful point of reference.

A 2020 issue of the City: Analysis of Urban Change, Theory, Action journal dedicated to the phenomenon of urban fallism included a contribution on the fate of public monuments during the Russian Revolution of 1917—an episode that remains an obligatory reference point to any discussion of monumental art in the context of popular uprisings.41 A monarchy headed by the Romanov family that had been on the Russian throne for three centuries collapsed in a matter of months.42 Seemingly overnight, the vast Russian Empire transformed into the first socialist country in the world, the dizzying pace of this change was astonishing to those bearing witness as it has been for subsequent generations. This major transformation actively included a revision of the country’s mnemonic landscape: as Tsarist monuments were removed across the country, Russia’s revolutionary leaders and artists alike began debating what kind of public monuments and urban design would be suitable for commemorating the collective action that had delivered revolution. The reach of this debate owed precisely to its focus on not simply eliminating the past, but courageously reimagining the present and offering an alternative to “the binary discourse of veneration and annihilation” of existing structures.43

The most fascinating and innovative contribution came from Russia’s avant-gardists—a cohort of young artists whose revolutionary political views, often shaped precisely through student activism, matched their radical aesthetic ambitions.44 Yet while these artists are often remembered for their bold calls to destroy the past, their true genius was in fact their profound ability to imagine a type of artistic production (including monumental art) fit for a radically new society—one that no longer relied on traditional artistic vocabulary. The most remarkable solution proposed by Russia’s avant-garde was Vladimir Tatlin’s well-known Monument to the Third International (1918–20). Known popularly as “Tatlin’s Tower,” this monument was never built—yet its design continues to reverberate within artistic imagination to this day.

Work on the Monument to the Third International commenced within the framework of a large official campaign.45 In April 1918, Vladimir Lenin unveiled his famous Plan for Monumental Propaganda—an ambitious creative undertaking aimed at inspiring and fortifying new values within the Russian population by placing a series of monuments dedicated to revolutionary figures around Petrograd and Moscow.46 As the outcome of the October Revolution still hung in the balance, and Russia became enthralled in civil war between revolutionary forces and remnants of the old Tsarist regime, the new Soviet leadership understood that the conflict would not be won by bayonets alone, but rather that the arts—and more specifically public art—would play a critical role in stimulating revolutionary mobilisation. While the old Tsarist sculptures were being pulled down, 67 new monuments were commissioned for Petrograd and Moscow—but most of these took the traditional figurative form of a full-length sculpture or a bust. Avant-garde artists such as Tatlin argued against this form of production, noting that the old formats could not capture the collectivist and activist nature of the new revolutionary power. As Tatlin’s colleague, art critic and writer Nikolai Punin would emphasise, form just like content communicates the value system and mindset of a society.47 In other words, Punin realised that it was not sufficient to modify or occupy old artistic forms—instead, artists would need to find new ones.

Tatlin’s proposal represented an alternative vision, dramatically different to the traditional commemorative statues and busts that were produced as part of this campaign—and which writer Ilya Ehrenburg characterised as an “epidemic of plaster idiots.”48 Tatlin’s monument aimed both to commemorate the revolution and its collectivist principles, but also to maintain activist momentum among the population. Indeed, this work was conceptualised as a powerful weapon of societal agitation at a critical moment in the revolutionary process—a moment in which victory was still far from certain, and the ability of the population to persevere would be decisive. For the avant-garde artists, the traditional form of monuments simply did not fit this complex brief. In content, these monuments celebrated individual heroes, which went against collectivist principles. In form, familiar solutions presented both a potential ideological threat, in that they inevitably propagated a worldview of the past.

By stark contrast, Tatlin’s Tower offered something radically different in both form and content.49 The artist began working on a prototype in 1918, and towards the end of 1920 a large-scale wooden model was exhibited in Petrograd and Moscow. Tatlin chose a double spiral framework which housed a cube, pyramid, and cylinder in an ascending order, capped with a hemisphere. The cube was intended as a venue for international meetings and conferences, and designed to revolve annually; the pyramid was envisaged as an administrative centre and intended to rotate on a monthly basis; and the cylindrical section would house a propaganda centre and revolve daily. This propaganda section was to be a hive of media activity, complete with an information bureau, a publishing section for producing newspapers, proclamations, brochures, and manifestos, a radio and telegraph broadcasting station, and a projector that would continually beam slogans onto the skies above. The top hemisphere would rotate hourly and also serve propaganda purposes.

Inspiration for this construction was to a significant degree drawn from the contemporary agitational trains and boats that Soviet leaders used to disseminate the latest news and revolutionary propaganda across Russia. These so-called agit-trains were decorated by artists with images and slogans, and the trains themselves contained cinema equipment, radios, printing presses, and libraries. As the trains travelled to meet audiences in the most distant corners of the vast country, they gave people in remote locations access to films, broadcasts, and publications, as carriages transported visual and print materials that supported onboard lectures, the work of mobile libraries, and educational exhibitions; rooftops meanwhile served as stages for theatre performances and political speeches. This was truly a fusion of the political, the artistic, the agitational, and the technological in support of the revolutionary campaign. It was the experience of working on these agitational projects that avant-garde artists drew on to reimagine a new, activist-built environment—including its monuments.

Tatlin’s Tower was never realised, although we know today that his construction was structurally sound and ‘buildable’—thereby challenging the prevailing label of utopianism as a synonym for impractical and impossible that is so readily associated with this famous work, and, by extension, the idea of radical change that it embodied.50 For its contemporaries, however, the point was not whether such a colossal steel and glass structure could have been built, but rather that it shifted artistic research towards a new mode of thinking that would capture the spirit of collective action and maintain its momentum, turning the monument, as Punin explained, into a place of “most intense movement.”51 This model was precisely what Staal has described as a work of art that is “both a carrier of propaganda art and a tool through which its users can partake in the collective propaganda effort”52—infrastructure for the transformative, emancipatory, and collective construction of life. The ability to reimagine reality through art is what distinguishes this historic “fallist” episode, and explains why this “paper monument” remains influential. As Svetlana Boym has noted, this work has acquired a second life by coming into material existence as artistic heritage through the realisation of many subsequent models, each serving as a “reservoir of unofficial utopian dreams,” where utopia designates a potential rather than foreclosure.53

Towards Transformative Propaganda for the Twenty-first Century

Precisely a century after Tatlin’s ground-breaking model for a new type of transformative propaganda, A History of Student Activism was beginning to take shape within a large-scale and long-term monumental campaign of its own. Since its foundation in 1946, the design of ANU’s campus has been underpinned by an effort to integrate the natural features of its location into its built environment.54 Around the campus, more than fifty public sculptures demonstrate the commitment to this objective—with the vast majority of these works drawing on the university’s own pool of talent, having been commissioned from artists who were graduates of, or lecturers and fellows at the ANU School of Art and Design. Hartshorn, Leong, and Carlin’s installation represents, on the one hand, a continuation of this logic: by involving generations of alumni and affiliates in the production of these public artworks, this campaign continues to demark the campus as a space for and of the students, while the focus on meaningful integration of these public artworks within the surrounding landscape and architecture echoes the aspiration towards an organic relationship with the land on which the campus is situated. At the same time, however, in its evolution, conception, and execution, A History of Student Activism departs from the set of figurative and abstract pieces that have historically defined this public collection, and in this way offers a new reference point for the future.

Much like its distant avant-garde predecessor, A History of Student Activism represents the physical manifestation of the agitational and activist ethos of a particular place and time. Its main conceptual source—the seventh issue of the Demos journal—was the product of a collective effort by ANU students to capture the history of student activism on their campus in a moment when some of the key sites of that history were being demolished. This issue of the journal operates simultaneously as an archive, capturing a history that has not previously been systematically documented or safeguarded; as an activist manual; and arguably as a work of propaganda art aimed at inspiring collective action. Contributions to this issue bring together materials that had previously been dispersed across national, organisation-based, or personal archives—from records of the ANU Students’ Association (ANUSA), the archives of the university’s flagship magazine ANU Reporter, and collections from ANU’s Noel Butlin Archive Centre (including recordings of lectures delivered as part of the first Women’s Studies course), to relevant oral history collections from the National Library and interviews with both past and present student activists conducted specifically for this publication. This archive informs contributions to this issue that together foreground a history of disobedience that challenged social injustices. At the same time, it stands as a compendium of activist methods and strategies used to achieve political change—from spectacular ‘trashing the joint’ interventions, to more subtle forms of everyday activism along with advice for maintaining hope that change is, indeed, possible. Finally, this issue of Demos is also a collection of creative work developed in support of activist causes, from poems and drawings to graphic design.

With A History of Student Activism, Hartshorn, Leong, and Carlin translated the content of—and impetus for—the Demos issue into spatial language in a way that maintains its deep archival quality, its collectivist ethos of production, and its activist potential. Leong’s redesign of the printed timeline, with additional research carried out by Emma Cupitt, hovers lightly against the white background, evocative of a computer-generated word cloud, or perhaps a presentation poster designed to accompany a student assignment. The lightness of the design does nothing to temper the seriousness of its content, from the 1981 Women Against Rape in War demonstrations organised on ANZAC day that audaciously challenged one of the major glorifying narratives of national history, to the 2014 campaign to achieve ANU’s divestment from fossil fuel companies. This same logic underpins the two video installations. Hartshorn’s piece captures, through image and sound, a record of Indigenous Australians’ struggle for rights, with physical and emotional traces of past fights visible to this day. Indeed, as the title of the piece suggests, the dust has all but settled. Carlin’s own piece is a moving and powerful homage to women who championed change not only within ANU but across Australia, by introducing a feminist perspective in both academic practice and political activism forming a titular ‘critical mass’ at a point in time that would bring about long-awaited change. The set of interviews are all staged in these women’s homes, with Carlin here drawing attention to alternative lines of and possibilities for activism within the domestic setting. Interspersed with footage of Canberra from the second half of the twentieth century, the viewer is faced with an austere layout of the Australian capital defined by monumental design in which humans can only feel small, but which, as the installation shows, has not extinguished the activist impulse.

The strongest aspect of the installation, captured in each of its three components and collectively, is certainly the continuity of student activism at the ANU, and with this a call for intergenerational solidarity in tackling urgent issues. It is through this element that the artwork achieves its transformative potential, and extends beyond merely providing a record of a history that remains on the margins of the national narrative about the past, or a commemoration of the achievements produced through collective action. This sense of continuity captures the attention of viewers, who are left to ponder whether or not they have just seen the same issues recently covered by the media. The format of the piece seeks to inspire this very conversation, and in this way the artwork represents an important launchpad for future engagement. In a more structured manner, this conversation is also provoked by the inclusion of the piece within ANU curriculum, as part of the School of Art and Design’s course on the politics of memory in contemporary art practice.55

A History of Student Activism is envisaged as being open-ended, and in this way intended for viewers to engage with one or two aspects at a time, and to continue returning. Its location within a space for contemplation, discussion, and encounter invites this form of regular interaction. In this way, though remote in time and space, this public artwork echoes the principles set out in Tatlin’s model for an activist monument—a space for meeting and discussion; a locus of information, education, and agitation that, by synthesising various media, extends its reach. It is precisely the installation’s multifaceted nature—which extends across a diverse series of platforms including the print and online publication of the Demos issue, live and streamed public launches, a university course, and even this article—that helps to overcome the limits that A History of Student faces due to its location within the premises of an elite institution. In its content, the installation speaks to the continuity of activism; in its form, it captures the continuity of an artistic and activist impulse that is permanently searching for ways to break down boundaries in a quest to actualise a different and better reality. Today, as we come to terms with the fact that our response to the major challenges we face will undoubtedly define our planetary future, we have much to gain from answering Staal’s call to harness the potential of transformative propaganda art—and in the process reactivate the arsenal of political and artistic forms that have previously captured the power of collective action. Indeed, as long-time activist Liz O’Brien notes in her interview with Carlin, in observing that much has changed over the past half century, we must also acknowledge “but not nearly enough.”

-

Thank you to the three reviewers of this article—I am grateful for your insightful and informative comments. I am also thankful for the feedback I received from colleagues following a presentation of this work at the ANU School of History seminar series. Thank you to the artists and the curator of A History of Student Activism, and in particular Alex Martinis Roe and Esther Carlin for their assistance in developing this piece.

Jonas Staal, Propaganda Art in the 21^st^ Century (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2019). This publication is based on Staal’s “Propaganda Art From the 20^th^ to the 21^st^ Century” (PhD diss., Leiden University, 2018), available at: https://monoskop.org/images/8/8e/Staal_Jonas_Propaganda_Art_from_the_20th_to_the\_\

21st_Century_2018.pdf. The article draws on both versions of Staal’s study. ↩

-

Staal, “Propaganda Art From the 20^th^ to the 21^st^ Century,” 13. ↩

-

Staal, Propaganda Art in the 21^st^ Century, 44–45. ↩

-

Staal, Propaganda Art in the 21^st^ Century, 9. ↩

-

Staal, Propaganda Art in the 21^st^ Century, 2; see also Staal, Propaganda Art From the 20^th^ to the 21^st^ Century, 18. ↩

-

Louis Althusser, “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses,” in Louis Althusser, On the Reproduction of Capitalism, Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (New York: Verso, 2014), 265. ↩

-

Leonard Williams, “Althusser on Ideology: A Reassessment,” New Political Science 14, no. 1 (1993): 57. ↩

-

On this point, it is useful to consult Ana Janevski and Roxana Marcoci with Ksenia Nouril, Art and Theory of Post-1989 Central and Eastern Europe: A Critical Anthology (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2018). ↩

-

On this debate, see, for example, Boris Groys, “The Art of Totality,” in Landscape of Stalinism: The Art and Ideology of Soviet Spaces, ed. Evgeny Dobrenko and Eric Naiman (Seattle: Washington University Press, 2003), 96–122. See also Igor Golomstock, Totalitarian Art in the Soviet Union, the Third Reich, Fascist Italy, and the People’s Republic of China (London: Collins-Harvill, 1990). ↩

-

See, for example, James A. Leigh, Space and Revolution, Projects for Monuments, Squares, and Public Buildings in France, 1789–1799 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1991), 3–6; and Joes Segal, Art and Politics: Between Purity and Propaganda (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2016), 7–16. ↩

-

Staal, Propaganda Art in the 21^st^ Century, 9. ↩

-

Staal, Propaganda Art in the 21^st^ Century, 9; 148. ↩

-

Staal, Propaganda Art in the 21^st^ Century, 190; See Peter Weibel, “Preface” to Global Activism, Art and Conflict in the 21^st^ Century, ed. Peter Weibel (Karlsruhe: ZKM|Centre for Art and Media, 2013), 23. ↩

-

On the development of new monument forms that aim to articulate alternative collective narratives see, for example, James E. Young, “Germany’s Memorial Question: Memory, Counter-Memory, and the End of Monument,” The South Atlantic Quarterly 96, no. 4 (1997): 853–880; Catherine De Lorenzo, “More Than Skin and Bones: A Recent Australian Public Art Project Re-evaluating History,” De arte 54, no. 2 (2019): 22–40. ↩

-

Demos Journal, ‘Student Activism’ 7 (February 2018), available at: https://demosjournal.com/issues/issue-7/. An electronic version of the issue, which replicates the layout of the print journal, is available at: https://issuu.com/demosjournal/docs/demos_web. Carlin and Filmer-Sankey’s work on this installation took place in concert with the production of the seventh issue of Demos, and was incorporated into the launch of the issue. The temporary installation comprised a board with handwritten text and images from various archives, and a series of unedited oral history interviews within two small listening pods. Participants in those interviews included Chris Swinbank, Judy Turner, Julius Roe, Odette Shenfield, Rashna Farrukh, Steph Cox, Stevie Skitmore, Yen Eriksen, and Tim McCann. The installation was displayed in the Brian Kenyon Student Space (prior to the campus redevelopment) for several months. Photographs featuring this installation are available on the Demos Facebook page, February 14, 2018: https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?vanity=demosjournal&set=a.2021071524784317 ↩

-

On the history of political activism in Australia, see, for example, Clive Hamilton, What Do We Want? The Story of Protest in Australia (Canberra: National Library of Australia Publishing, 2016). ↩

-

See, for example, Michael Young, “Where I Work: Richard Bell, A Firebrand Artist Fighting for Indigenous Rights,” ArtAsiaPacific 113 (May/June 2019): 147–150. ↩

-

See, for example, the work of Alex Martinis Roe, and in particular To Become Two (2014–17), available at: https://www.alexmartinisroe.com/To-Become-Two; Jane Devery, “Living Libraries: Feminist Histories in the Art of Emily Floyd,” National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, accessed September 21, 2021, https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/living-libraries-feminist-histories-in-the-art-of-emily-floyd/. ↩

-

John Reed, Ten Days that Shook the World (New York: Boni & Liveright, 1919). ↩

-

On the intersection between the pandemic and climate change in Australia see, for example, Tim Flannery, The Climate Cure: Solving the Climate Emergency in the Era of COVID-19 (Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2020). ↩

-

Joshua Clover, Riot. Strike. Riot: The New Era of Uprisings (New York: Verso, 2016). ↩

-

Clover, Riot. Strike. Riot, 18. ↩

-

Brenda Schmahmann, “The Fall of Rhodes: The Removal of a Sculpture from the University of Cape Town,” Public Art Dialogue 6, no. 1 (2016): 90. ↩

-

Schmahmann, “The Fall of Rhodes,” 90; see also Sybille Frank and Mirjana Ristic, “Urban Fallism, Monuments, Iconoclasm, and Activism,” City: Analysis of Urban Change, Theory, Action 24, no. 3–4 (2020): 552–564. ↩

-

Schmahmann, “The Fall of Rhodes,” 90. ↩

-

Paul M. Garton, “#Fallism and Alter-globalisation: South African Student Movements as Multi-institutional Responses to Globalisation,” Globalisation, Societies, and Education 17, no. 4 (2019): 407–418. ↩

-

See Garton, “#Fallism and Alter-globalisation,” 407–418; Sabine Marschall, “Targeting Statues: Monument ‘Vandalism’ as an Expression of Sociopolitical Protest in South Africa,” African Studies Review 60, no. 3 (2017): 203–219. ↩

-

Frank and Ristic, “Urban Fallism,” 552–564. ↩

-

Frank and Ristic, “Urban Fallism,” 552–564; see also Dario Gamboni, The Destruction of Art, Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolution (London: Reaktion Books, 1997). ↩

-

James Rann, “Maiakovskii and the Mobile Monument: Alternatives to Iconoclasm in Russian Culture,” Slavic Review 71, no. 4 (2012): 767. On the use of terms iconoclasm versus vandalism in destruction of monuments and works of art, see, for example, Gamboni, The Destruction of Art, 13–24. ↩

-

Nancy Spector, Maurizio Cattelan: All (New York: Guggenheim Museum Publication, 2011), 54–57; 241–242. ↩

-

Claire Shea, “Maurizio Cattelan, L.O.V.E. (2010),” Institute for Public Art, accessed September 21, 2021, https://www.instituteforpublicart.org/case-studies/l.o.v.e/. ↩

-

See, for example, Post-Post-Soviet? Art, Politics, and Society in Russia at the Turn of the Decade, ed. Marta Dziewanska, Ekaterina Degot, and Ilya Budratskis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013); Iva Glisic, “From Futurism to Pussy Riot: Russia’s Tradition of Aesthetic Disobedience,” History Australia 13, no. 2 (2016): 195–212. ↩

-

Glisic, “From Futurism to Pussy Riot,” 195–212. ↩

-

“How Statues Are Falling Around the World,” The New York Times, June 24, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/24/us/confederate-statues-photos.html. ↩

-

See, in particular, “George Floyd was Infected with COVID-19, Autopsy Reveals,” Reuters, June 4, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-minneapolis-police-autopsy-idUSKBN23B1HX. See also April Thames, “Coronavirus Deaths and those of George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery Have Something in Common: Racism,” The Conversation, June 9, 2020, https://theconversation.com/coronavirus-deaths-and-those-of-george-floyd-and-ahmaud-arbery-have-something-in-common-racism-139264. ↩

-

“Edward Colston Statue: Protesters Tear Down Slave Trader Monument,” BBC News, June 8, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-52954305. ↩

-

Camron Slessor and Eugene Boisvert, “Black Lives Matter Protests Renew Push to Remove ‘Racist’ Monuments to Colonial Figures,” ABC News, June 10, 2002, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-06-10/black-lives-matter-protests-renew-push-to-remove-statues/12337058 ↩

-

Staal, Propaganda Art in the 21^st^ Century, 187. ↩

-

Staal, Propaganda Art in the 21^st^ Century, 62. ↩

-

Aaron J. Cohen, “The Limits of Iconoclasm: The Face of Tsarist Monuments in Revolutionary Moscow and Petersburg, 1917–1918,” City: Analysis of Urban Change, Theory, Action 24, no. 3–4 (2020): 616–626. ↩

-

See, for example, Peter Holquist, Making War, Forging Revolution: Russia’s Continuum of Crisis, 1914–1921 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002); Sheila Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008); Laura Engelstein, Russia in Flames, War Revolution, Civil War, 1914–1921 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018). ↩

-

Rann, “Maiakovskii and the Mobile Monument,” 783. ↩

-

Iva Glisic, The Futurist Files, Avant-Garde, Politics, and Ideology in Russia, 1905–1930 (DeKalb, Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press, 2018), 19–30. ↩

-

Glisic, The Futurist Files, 68–87. ↩

-

“On the Dismantling of Monuments Erected in Honour of the Tsars and their Servants and on the Formulation of Projects for Monuments to the Russian Socialist Revolution,” April 12, 1918, published in Izvestiia April 14, 1918. For Tatlin’s comment on this decree, see V. Tatlin, S. Dymshits-Tolstaia (published by John Bowlt), “Memorandum from the Visual Arts Section of the People’s Commissariat for Enlightenment to the Soviet of People’s Commissars: Project for the Organization of Competitions for Monument to Distinguished Persons (1918),” Design Issues 1, no. 2 (1984): 70–74. ↩

-

Glisic, The Futurist Files, 72–87. ↩

-

Glisic, The Futurist Files, 73; English translation of the quote in Svetlana Boym, “Ruins of the Avant-Garde, From Tatlin’s Tower to Paper Architecture,” in Ruins of Modernity, ed. Julia Hell and Andreas Schönle (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2010), 61. ↩

-

Nikolai Punin, Pamiatnik III Internatsionala (Peterburg: Izdanie Otdela Izobrazitel’nykh Iskusstv N. K. P., 1920); For an English translation of this text see Nikolai Punin, “The Monument to the Third International,” in Art in Theory 1900–1990, An Anthology of Changing Ideas, ed. Charles Harrison and Paul Woods (Oxford: Blackwell, 1993), 311–315. ↩

-

N. Punin, Pamiatnik III Internatsionala (Peterburg: Izdanie Otdela Izobrazitel’nykh Iskusstv N. K. P., 1920); For an English translation of this text see Nikolai Punin, “The Monument to the Third International,” in Charles Harrison and Paul Woods eds., Art in Theory 1900-1990, An Anthology of Changing Ideas (Oxford: Blackwell, 1993), 311-315. ↩

-

Klaus Bollinger and Florian Medicus, Unbuildable Tatlin?! (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2012). ↩

-

N. Punin, “O pamiatnikakh,” Iskusstvo kommuny no. 14 (9 March 1919): 3, in Rann, “Maiakovskii and the Mobile Monument,” 776. ↩

-

Staal, Propaganda Art in the 21st Century, 59. ↩

-

Boym, “Ruins of the Avant-Garde, From Tatlin’s Tower to Paper Architecture,” 70. ↩

-

Australian National University, Sculpture Walk, available at: https://services.anu.edu.au/files/guidance/Sculpture-Walk-Brochure_0.pdf ↩

Iva Glisic is a Visiting Fellow at the Australian National University. Her work explores the history of radical ideas and the relationship between art and politics, with a particular focus on historical and contemporary forms of artistic activism in Russia and Eastern Europe. She is the author of the award-winning book The Futurist Files: Avant-Garde, Politics, and Ideology in Russia, 1905–1930 (Dekalb, Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press, 2018).

Bibliography

- Althusser, Louis. On the Reproduction of Capitalism, Ideology, and Ideological State Apparatuses. New York: Verso, 2014.

- Australian National University, School of Art and Design. “Politics of Memory: Video, Installation, Sculpture, Documentary and Monuments.” Accessed September 21, 2021. https://programsandcourses.anu.edu.au/course/ARTV2802.

- Australian National University. “Sculpture Walk.” Accessed September 21, 2021.

- https://services.anu.edu.au/files/guidance/Sculpture-Walk-Brochure_0.pdf.

- Bollinger, Klaus and Florian Medicus. Unbuildable Tatlin?! Berlin: De Gruyter, 2012.

- Clover, Joshua. Riot. Strike. Riot: The New Era of Uprisings. New York: Verso, 2016.

- Cohen, Aaron J. “The Limits of Iconoclasm: The Face of Tsarist Monuments in Revolutionary Moscow and Petersburg, 1917–1918.” City: Analysis of Urban Change, Theory, Action 24, no. 3–4 (2020): 616–626.

- De Lorenzo, Catherine. “More Than Skin and Bones: A Recent Australian Public Art Project Re-evaluating History.” De arte 54, no. 2 (2019): 22–40.

- Devery, Jane. “Living Libraries: Feminist Histories in the Art of Emily Floyd.” National Gallery of Victoria. Accessed September 21, 2021. https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/living-libraries-feminist-histories-in-the-art-of-emily-floyd/.

- Dobrenko, Evgeny and Eric Naiman, eds. Landscape of Stalinism: The Art and Ideology of Soviet Spaces. Seattle: Washington University Press, 2003.

- Dziewanska, Marta, Ekaterina Degot, and Ilya Budratskis, eds. Post-Post-Soviet? Art, Politics, and Society in Russia at the Turn of the Decade. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013.

- “Edward Colston Statue: Protesters Tear Down Slave Trader Monument.” BBC News, June 8, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-52954305.

- Engelstein, Laura. Russia in Flames: War, Revolution, Civil War, 1914–1921. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila. The Russian Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Flannery, Tim. The Climate Cure: Solving the Climate Emergency in the Era of COVID-19. Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2020.

- Frank, Sybille and Mirjana Ristic. “Urban Fallism: Monuments, Iconoclasm, and Activism.” City: Analysis of Urban Change, Theory, Action 24, no. 3–4 (2020): 552–564.

- Gamboni, Dario. The Destruction of Art, Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolution. London: Reaktion Books, 1997.

- Garton, Paul M. “#Fallism and Alter-globalisation: South African Student Movements as Multi-institutional Responses to Globalisation.” Globalisation, Societies, and Education 17, no. 4 (2019): 407–418.

- “George Floyd Was Infected with COVID-19, Autopsy Reveals.” Reuters, June 4, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-minneapolis-police-autopsy-idUSKBN23B1HX.

- Glisic, Iva. The Futurist Files: Avant-Garde, Politics, and Ideology in Russia, 1905–1930. DeKalb, Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press, 2018.

- Glisic, Iva. “From Futurism to Pussy Riot: Russia’s Tradition of Aesthetic Disobedience.” History Australia 13, no. 2 (2016): 195–212.

- Golomstock, Igor. Totalitarian Art in the Soviet Union, the Third Reich, Fascist Italy, and the People’s Republic of China. London: Collins-Harvill, 1990.

- Hamilton, Clive. What Do We Want? The Story of Protest in Australia. Canberra: National Library of Australia Publishing, 2016.

- Harrison, Charles and Paul Woods, eds. Art in Theory 1900–1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas. Oxford: Blackwell, 1993.

- Hell, Julia and Andreas Schönle, eds. Ruins of Modernity. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2010.

- Holquist, Peter. Making War, Forging Revolution: Russia’s Continuum of Crisis, 1914–1921. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002.

- “How Statues Are Falling Around the World.” The New York Times. June 24, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/24/us/confederate-statues-photos.html.

- Janevski, Ana and Roxana Marcoci with Ksenia Nouril. Art and Theory of Post-1989 Central and Eastern Europe: A Critical Anthology. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2018.

- Leigh, James A. Space and Revolution: Projects for Monuments, Squares, and Public Buildings in France, 1789–1799. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1991.

- Marschall, Sabine. “Targeting Statues: Monument ‘Vandalism’ as an Expression of Sociopolitical Protest in South Africa.” African Studies Review 60, no. 3 (2017): 203–219.

- “On the Dismantling of Monuments Erected in Honour of the Tsars and their Servants and on the Formulation of Projects for Monuments to the Russian Socialist Revolution.” Izvestiia. April 14, 1918.

- Punin, Nikolai. Pamiatnik III Internatsionala. Peterburg: Izdanie Otdela Izobrazitel’nykh Iskusstv N. K. P., 1920.

- Punin, Nikolai. “O pamiatnikakh.” Iskusstvo kommuny no. 14 (9 March 1919): 3.

- Rann, James. “Maiakovskii and the Mobile Monument: Alternatives to Iconoclasm in Russian Culture.” Slavic Review 71, no. 4 (2012): 766–791.

- Reed, John. Ten Days that Shook the World. New York: Boni & Liveright, 1919.

- Schmahmann, Brenda. “The Fall of Rhodes: The Removal of a Sculpture from the University of Cape Town.” Public Art Dialogue 6, no. 1 (2016): 90–115.

- Segal, Joes. Art and Politics: Between Purity and Propaganda. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2016.

- Shea, Claire. “Maurizio Cattelan, L.O.V.E. (2010).” Institute for Public Art. Accessed September 21, 2021. https://www.instituteforpublicart.org/case-studies/l.o.v.e/.

- Slessor, Camron and Eugene Boisvert. “Black Lives Matter Protests Renew Push to Remove ‘Racist’ Monuments to Colonial Figures.” ABC News. June 10, 2002. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-06-10/black-lives-matter-protests-renew-push-to-remove-statues/12337058.

- Spector, Nancy. Maurizio Cattelan: All. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publication, 2011.

- Staal, Jonas. Propaganda Art in the 21^st^ Century. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2019.

- Staal, Jonas. Propaganda Art From the 20^th^ to the 21^st^ Century. PhD diss., Leiden University, 2018.

- Tatlin, Vladimir and Sofya Dymshits-Tolstaia, “Memorandum from the Visual Arts Section of the People’s Commissariat for Enlightenment to the Soviet of People’s Commissars: Project for the Organization of Competitions for Monument to Distinguished Persons (1918).” Design Issues 1, no. 2 (1984): 70–74.

- Thames, April. “Coronavirus Deaths and those of George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery Have Something in Common: Racism.” The Conversation. June 9, 2020. https://theconversation.com/coronavirus-deaths-and-those-of-george-floyd-and-ahmaud-arbery-have-something-in-common-racism-139264.

- Weibel, Peter, ed. Global Activism, Art and Conflict in the 21^st^ Century. Karlsruhe: ZKM|Centre for Art and Media, 2013.

- Williams, Leonard. “Althusser on Ideology: A Reassessment.” New Political Science 14, no. 1 (1993): 47–66.

- Young, James E. “Germany’s Memorial Question: Memory, Counter-Memory, and the End of Monument.” The South Atlantic Quarterly 96, no. 4 (1997): 853–880.

- Young, Michael. “Where I Work: Richard Bell, A Firebrand Artist Fighting for Indigenous Rights.” ArtAsiaPacific, no. 113 (May/June 2019): 147–150.