Abstract Sculpture or Colonial Monument? Deception and Reception in the Commemorative Landscape of Newcastle, Australia, 1970 to 2020

The 250th anniversary of Lieutenant James Cook’s landing in Australia coincided in 2020 with mounting critique of colonial monuments globally, notably in North American and South African campaigns against statues of imperialists and industrialists, now reclassified and outed as slaveholders and slave traders. In a replica of the national reckonings that occurred in 1938, 1970, and 1988, a further wave of introspection and protest approached these shores having already washed through other destinations on the Endeavour’s Pacific route. Cook statues in New Zealand were defaced in 2019 and not for the first time. Australia too had been building up to the occasion; Thomas Woolner’s monument to the explorer in Hyde Park, Sydney was targeted in 2017 and again in 2020, together with its peer in Randwick. His effigy in St Kilda, Melbourne was disfigured in 2018. Given the present scrutiny of monuments, the relationship of Margel Hinder’s Captain James Cook Memorial Fountain (1966–70, fig. 1) to colonial narratives presents an interesting case for study, which art-historical accounts have so far elided. The 2021 retrospective exhibition Margel Hinder: Modern in Motion is the most recent and visible example, inscribing the artist’s work solely within an aesthetic history of abstraction while neglecting its political aspects.1

Next to figurative bronzes of James Cook, Hinder’s fountain in Newcastle’s Civic Park is an unlikely target of decolonising action. Nothing in its form, iconography, or the original commission indicate any relationship with colonial celebration. And yet names are powerful. Inaugurated as Civic Park Fountain, it was renamed as a memorial to the British explorer in 1970, four years after its completion. Adjacent bronze plaques (fig. 2) exalting Cook’s discovery were fitted. Overnight, an alchemical transformation took place whereby a publicly maligned modernist sculpture became a much-lauded memorial to the founding of a nation. As an autonomous object of art, Hinder’s work was criticised as a gratuitous sinkhole of public funds; as a monument to nationalist pride it found acceptance in an atmosphere hostile to abstraction and public spending on the arts. In 2020, sentiment changed and that same act of naming, which in 1970 inured Hinder’s fountain to attacks from cultural conservatives, now exposes the unresolved violence in the originary myths of the nation. At the commencement of writing this paper, only one of the two “discovery plaques” remained; the westernmost example disappeared in June 2020 in a fate identical to that suffered by the Woolner statue’s inscription in 1991.2

The origins of a sculptural centerpiece for Civic Park date to 1961 when the Newcastle City Council called for submissions from “architects, sculptors, designers or other persons throughout Australia.”3 That it was to be a fountain—and an illuminated one no less—indicated a desire to associate the city with a verdant modernity. As demonstrations of the availability and abundance of drinking water at the heart of the metropole, fountains have long been a symbol par excellence of civic progress.4 This ambition continued a broader strategy for the industrial port city of Newcastle, including the construction of cultural amenities—a cultural centre, library, and art gallery—necessary for the betterment of a parochial working-class and ex-convict population. The Newcastle Art Gallery’s founding benefactor, ophthalmologist Roland Pope, stated his vision clearly: that “a steel city could have the best art gallery in the country.”5

The beautification of the park constituted a process of identity formation as Newcastle moved in violent fits and starts from its Indigenous origins through its convict past and glory days of steel production towards today’s ill-named “post-industrial” reality; a perpetually arriving future-present so far thwarted by ongoing shipping and expanded mining operations. Until the 1950s the land now known as Civic Park was criss-crossed with tracks for coal carts. Mining companies plied the rich seams of carbon of neighbouring Cooks Hill and shunted their export through the city centre en route to the harbour for loading onto ships. As local deposits dwindled, extraction travelled further up the Hunter valley, and the working-class suburb underwent gentrification; once humble miners’ terraces now fetch high prices.

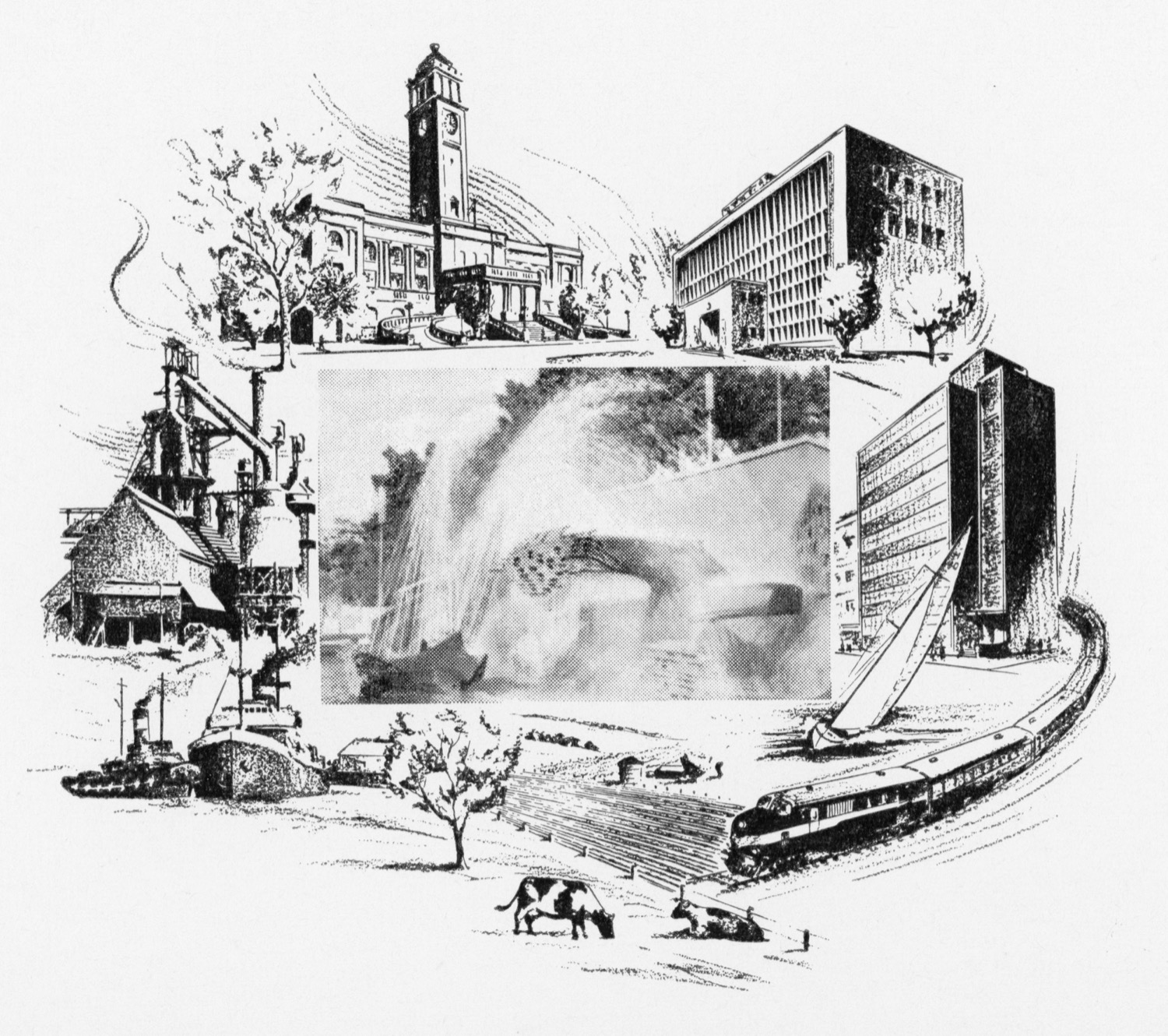

Rid of the railways marring the site, local councillors, and town planners set about describing a civic square, traversed by an axis of cultural and political landmarks, punctuated at one end by Civic Theatre (1929) and City Hall (1929), at the other by the War Memorial Cultural Centre (1957) and buttressed on the east by the Newcastle Art Gallery (1977). The construction of the Cultural Centre was followed by significant landscaping of the park including a wide dais, flanked by staircases, for the installation of a monument. Along the axis also stands a sandstone cairn later topped by a black granite obelisk, known as the Newcastle Civic Park War Memorial (established 1954; rededicated 2003). A figurative bronze of former lord mayor Joy Cummings was added in 2019 to the northernmost point of the axis on Hunter Street, extending its limits both physically and semantically. The chosen site for the fountain, to the front of the Cultural Centre and opposite City Hall, was therefore situated within a modest “monumental avenue” (figs. 3 and 4).

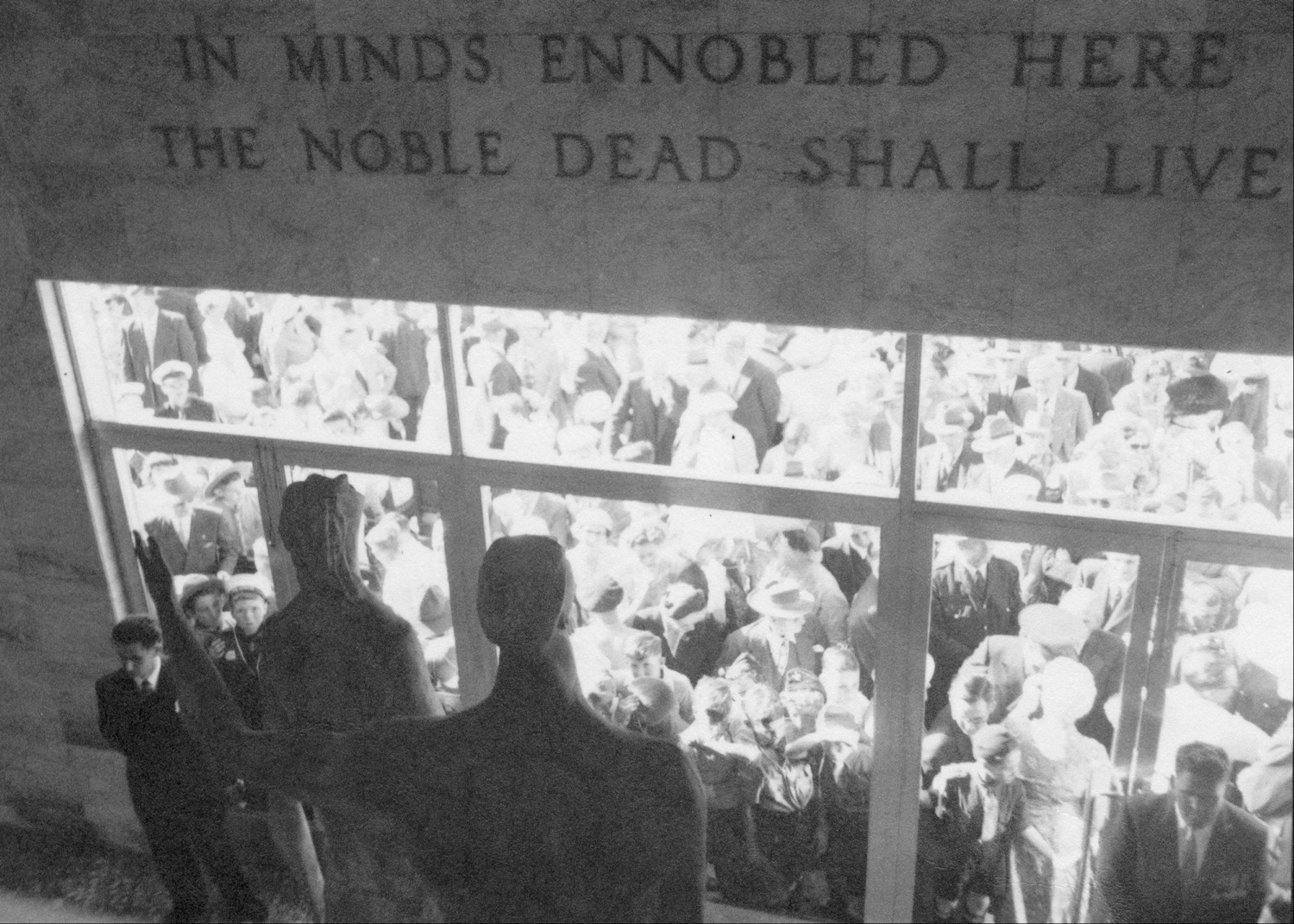

The placement of monuments along this axis demonstrates the close relationship between culture, war, and nation in the conception of Newcastle’s urban space. Especially telling is the commemorative function of the Cultural Centre, home to a public library, local history archives, gallery and, initially, a conservatorium. On entering the foyer, the visitor encounters two Lyndon Dadswell figures (1954–57), broken sword at their feet, looking upward at an inscription: “In minds ennobled here, the noble dead shall live” (fig. 5). The foyer engulfs the citizen in a vision of art as commemorative instrument and speaks of culture’s debt to belligerent nationalism for its survival, as if declaring “Thanks to war we may now read and enjoy art.” Such sentiment found echo in the Australian War Memorial’s announcement in 2018 of a $498 million expansion to commemorate recent military operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, the Solomon Islands and East Timor.6 This investment dramatically outstrips support—through the Australia Council and state government bodies—of the small to medium arts sector, more inclined towards independent and critical cultural expression.7 According to the historical truism, political power brokers employ culture as a transactional nation-building tool, epitomised by former politician Tony Abbott’s advocacy of Anzac. Culturally conservative Australian governments do not neglect the arts but are instead highly selective in allocating funding to projects that promote an ideologically constructed image of the nation.8

Patronage, Reception, and Interpretation of the Civic Park Fountain

On completion of the fountain in 1966, none could have anticipated its assimilation to patriotic celebration. Neither the competition terms nor the artist, Margel Hinder, contemplated anything remotely related to a memorial, much less one to Cook. The design won with a “clear and undoubted lead” over ninety other entries according to a panel formed by professor of urbanism Denis Winston, architect Eric C. Parker, and Newcastle City Art Gallery’s inaugural director, Gil Docking. The judges deemed the horizontal, non-figurative composition advantageous in not competing with the verticals of the nearby church spire, City Hall tower or the standing Dadswell figures framed behind by the Cultural Centre. They perceived in its forms the “strength of geological formations; of eroded rock on the coast-line, of tunnelling formations in coal mines,” symbolism they affirmed as “well developed” and likely to be “readily appreciated” by its prospective public.9 Yet claims that the sculpture “represents the rock faces of the region’s coastline,” while frequent in the popular imagination, are no truer than its attribution to James Cook.10 Allusions to local environs in Hinder’s competition entry statement were more likely a calculated appeal to her audience’s tastes and expectations than a true reflection of her artistic language:

the shapes are intended to signify certain qualities that I feel are expressive of Newcastle—energy, vigor, a metallic strength typical of the city’s industry, etc., without being representational or descriptive [author’s emphasis].11

Hinder expressed similar sentiments to a local journalist shortly before the fountain’s inauguration, explaining that the sculpture has “a certain rugged character because I feel the city has that character.”12 Decades later Hinder recalled how she responded to 1960s Newcastle—“a masculine city, filled with industry”—through “big strong …, rough shapes”.13 While acknowledging that “some of the things around the city that influenced [her] include the rugged coastal cliffs … the old rock walls,” Hinder repeatedly rejected any mimetic quality in the sculpture: “Somebody thought that I based it on the rocks or something, of Newcastle, no.”14 Art historical accounts have insisted on reading naturalistic origins into even her most doggedly non-representational work. Accordingly, the textured vertical and horizontal piping of the Reserve Bank and Civic Park sculptures was inspired by the play of moonlight across the giant bamboo from Margel’s bedroom window.15 In contrast, the artist herself presents the relationship between nature and her work as one of loose inspiration only: she postulates that although “the results of bushfires [and] burnt out trees” on field trips to Newcastle may have informed the fountain, “they weren’t directly related to [it].”16

These repeated negations of representationalism are consistent with Hinder the abstractionist, who from 1953 increasingly explained her practice in terms of volume, movement, and light.17 A reading of David Thomas’ 1973 catalogue or Ian Cornford’s 2013 monograph show that Hinder’s smaller figurative wooden pieces, so characteristic of her 1940s work, were replaced by large-scale abstraction by the 1950s. A statement by the artist in 1992 summed up her approach as “the relationship of shape and space and how one organizes space … It’s interpreting these things into a sculptural language.”18 Hinder is most convincing when she explains her monumental work in forceful, uncompromising terms. Her defence of the Reserve Bank sculpture in Martin Place, Sydney—both contemporaneous and visually similar to the Civic Park fountain—is exemplary: “It depicts nothing and represents nothing.” Indeed, the terms of the Reserve Bank competition in 1962 required no symbolism.19 On the fountain itself, a year before her death the artist put any debate to rest: “[it] doesn’t represent anything … I don’t believe symbolising is part of our age.”20 These are the statements of a militant abstractionist, in whom art historian and critic Bernard Smith censured “the pretension that the abstract and formalist art of the time was the only viable visual art.”21

The selection of a non-figurative design from a total of ninety-one entries was a declaration of war in 1960s Australia. The antagonism of modernism—particularly abstraction—meant that the sculpture was condemned by reactionary critics as a “boot last” and a “pile of junk.”22 A rival camp of figurative artists led by Smith had in 1959 produced The Antipodean Manifesto, as “a protest, inter alia, against a complete dominance of Australian painting by US-based kinds of abstraction and the formalist aesthetic that accompanied it.”23 As a US-expat artist trained in American schools through the 1920s and 1930s, Hinder was at the frontline of aesthetic warfare.

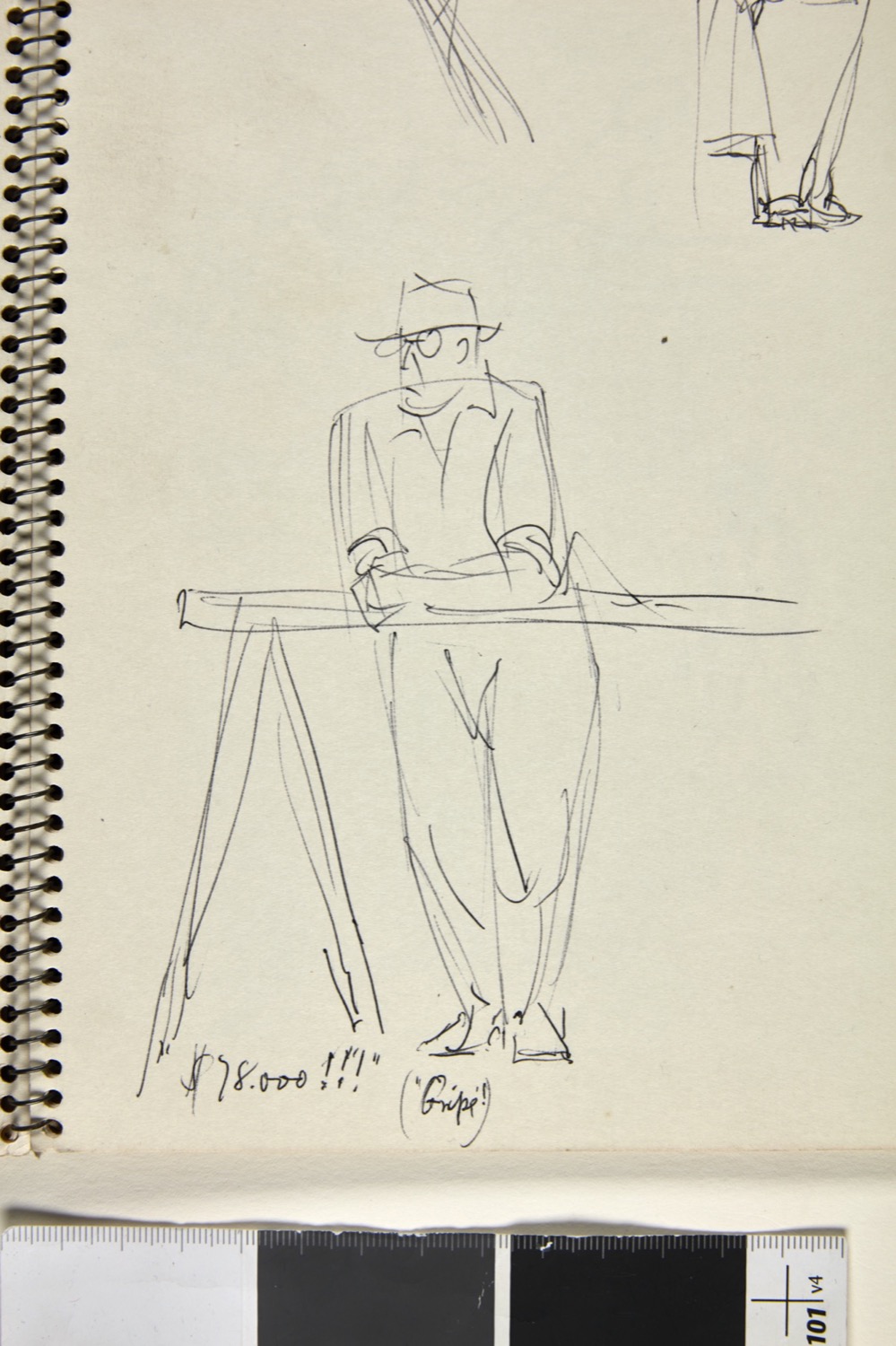

Contemporary art was not a common sight at the time of the judges’ decision in 1961; only four years prior to the competition launch the first exhibition space for art opened, the Newcastle City Art Gallery, on the second floor of the War Memorial Cultural Centre. Pope’s donation in 1945 of 123 works had languished in storage for twelve years awaiting a serviceable venue; it would wait a further twenty before it received a dedicated gallery. Anne von Bertouch’s commercial galleries—whose stables grew to include Arthur Boyd, David Boyd, Lloyd Rees, Judy Cassab, Margaret Olley, Donald Friend, and John Coburn–began trading early 1963.24 Despite this increasing demand for modern art in Australia, public acceptance was decidedly shaky. One of Hinder’s inner circle, artist and gallerist Carl Plate, recalled how “passers-by would hurl insults through the open door of the gallery when he hung [Ben] Nicholson’s work in the window” in conservative mid-century Sydney.25 The reception of non-representational work was further strained in the case of public work.26 The cost of Hinder’s fountain only served to sharpen criticism. Initial estimates of £20,000 ($40,000) had almost doubled by the time the work was completed. On-site spectators expressing their outrage at the public expense were recorded by Frank Hinder in sketches and poems (fig. 7).27 Counter to the model of popular subscription, which underwrites monuments as expressions of collective sentiment, funding did not come from spontaneous donors but government coffers.28 The same can be said of the sizeable spends on the 2015 Anzac centennial and the 2020 Cook sestercentennial celebrations, which provoked their own measure of indignation.

Further evidence of the top-down nature of the fountain’s genesis is the dedication plaque at its rear. This original bronze plate is as easy to miss as it is telling of the motives behind the commission. A full list of municipal representatives heads the credit roll, while sculptor Margel Hinder, the principal author of the work, appears in twenty-second position, on equal footing with the architects, builder, and town clerk W. Burges (fig. 8). Hinder was consulted on the wording and composition of the plaque, a detail significant for reasons that will become clear later. Without explicitly criticising the inclusion of so many minor names, Hinder referred Burges to the case of architect and renowned fountain designer Robert Woodward, who in his contemporaneous Morshead fountain (Royal Botanic Garden, Sydney, 1966) had omitted all but his own name from the plaque so numerous were his collaborators. Rather than request the removal of her patrons, however, Hinder politely recommends including the architectural firm and building company, as it “seems to be the accepted thing,” and changing her own title from the antiquated “sculptress” to “sculptor.”29 Any such concessions to Hinder were exceptions to the rule; decisions affecting the artistic integrity of the work were more often unilateral, most famously the installation of green lighting, which sparked a legal battle between the artist and City of Newcastle.

Seen from today’s prism, however, the most flagrant instance of co-optation is the renaming of the fountain for the 1970 bicentenary. Having witnessed opposition to state funding of public art, council members perceived a political opportunity in reframing the fountain as a memorial to Cook. Constant pushback at the cost of the fountain—via public, local press, and members of council—had impeded its full execution and ongoing maintenance. Temporary rails still bordered the staircases in place of suitable balustrades, and the lacklustre concrete formwork awaited appropriate sheathing. The complexity of the integrated plumbing required regular cleaning, which Margel and Frank undertook personally and at their own cost on regular trips from Sydney. Undesirable as all of this was, bicentenary funding from the Department of Local Government and Local Government Assistance Fund represented a timely opportunity to complete the fountain’s second stage. Loathe to recycle an existing monument, aldermen V.C. Bell and G.B. Rich conceded that the $15,000 raised would not do for a “fitting tribute.” Despite fears it would read as a “backhanded compliment” to Cook, council chose the rebranding of the Hinder fountain over proposals of new construction—including a band shell and new fountain—which were impossible to build within the budget and time available.30 Historian of Latin American art Rodrigo Gutiérrez Viñuales notes that such practicalities are typical of fiscally constrained state administrators, who “take advantage, at the lowest cost, of extant monuments, placing new commemorative inscriptions and plaques in bronze, all with a corresponding inaugural performance.”31 Yet even with these shortcuts the council had moved too slowly. The incomplete memorial formed the backdrop for the royal visit on 10 April (fig. 9). So thick were the crowds that Queen Elizabeth II, on her promenade from the Cultural Centre to City Hall, would not have seen the two identical bronze plaques had they been installed in time (fig. 10).32

The newly named Captain James Cook Memorial Fountain was thus rebranded in the public realm, despite its form and conceptual origins bearing no relation to Australia’s colonisation. It was another case of the “triumph of nationalism” over “international ideas” that Hinder biographer Ian Cornford observed in the Australian artistic and intellectual landscape from 1918 through the 1960s. Margel and the Sydney Second Wave Moderns, being “conscious, determined internationalists,” saw their work suffer as a result.33

Hinder’s insistence that “the fountain doesn’t represent anything” was all but forgotten, not to mention the original plaque with its litany of political piggy-backers. The artist and her vision again risked being buried under political jockeying and a second menace: patriotic fervour. Those who stop to read the dedications to Cook might, in earnest, confuse the sculpture’s characteristic forms for the bow, spars, and rigging of the Endeavour. Yet the renaming has been largely unsuccessful. Contrary to the declarations of the new plaques, the sculpture is still more commonly referred to as “the Civic Park fountain” and is associated with geological formations and civic grandeur in the popular imagination.

The 1970s coining has, on the other hand, been more effective in art-historical accounts, where the work has been canonised as the Captain James Cook Memorial Fountain with scarce attention paid to the semiotic and ideological ramifications. While the 1973 Newcastle Art Gallery catalogue privileges the fountain’s initial title and makes only discreet mention of the “amendment,” subsequent curatorial scholarship elides the issue altogether and refers only to the Cook memorial.34 Renée Free’s sustained interest in Hinder fails to explore the origins of the work’s title, while Luke Morgan’s 2008 text appears entirely ignorant of the sequence of events, stating that the “non-representational memorial … makes no direct allusion to its erstwhile subject.”35 Ian Cornford’s 2013 monograph does no more justice to the story: “Fortunately, the 1988 [sic] bicentenary of the discovery of Australia by Captain Cook stirred some interest in the fountain.”36 Again, in 2015, Cassi Plate’s curation of Newcastle Art Gallery’s Sydney 6: Hinders, Lewers, Plates, Abstract Artists fails to interrogate the chronology, motives and implications of the highly loaded name-change, as does Hinder’s landmark retrospective curated by Lesley Harding and Denise Mimmocchi in 2021.37 Aside from a brief commentary in July 2020 by Wiradjuri museum archivist Nathan mudyi Sentance, the issue has only been raised by council and local media when forced to by public indignation and the first plaque’s unsanctioned removal.38

Outrage has been a constant in the fountain’s life since its competitive selection, taking different turns according to the historical moment. The changing concerns of its audience has over time prompted novel reasons for protest, but the emotions have stayed the same. The public’s counter-modernist rage through the 1960s has morphed into decolonial wrath. Today’s indignation at the weaponisation of statuary and the whitewashing of Australian history was apparently not felt by the fountain’s first audience or by Hinder: a committed formalist and a North American to boot.

The Extent of Hinder’s Patriotism

Historical records suggest that, were Hinder consulted on the plan to transform her fountain into a memorial to Cook, she would not have found the reference to “discovery” as inappropriate as it now appears.39 A council letter from early 1970 informs the artist of an internal proposal to “complete the existing fountain in Civic Park and … consider naming [it] the ‘Captain James Cook Fountain’ (to mark the Bicentenary of his discovery of the eastern coast of Australia in 1770).” Hinder is invited to offer only her “views on the method of treatment of the immediate surrounds of the fountain.” Margel makes no mention of the title under consideration, limiting herself to objections of an aesthetic kind.40 How she felt about the content of the bicentennial plaques remains a mystery. If pressed, would she have voiced opposition, support, indifference or stoic acceptance? How might her US origins and personal politics have influenced her?

For Hinder’s peers, colonialism was a distant concern. The proliferation of commemorative projects and competitions in 1970 presented more of an opportunity for professional advancement than a cause for historical reflection. The Victorian Artist’s Society held the Captain Cook Bicentenary Art Awards with funding from the state government.41 References to the anniversary of European arrival in this competition and in the major annual awards are absent from finalists’ work, a clear exception being Edwin Tanner’s entry to the Society’s competition. Endeavour II alludes in its title to a second coming of Cook. Describing it as a “comparatively small picture of a white ship seen whimsically suspended on stocks in an open window frame,” one critic appreciated a blue seascape “impregnated with life-giving complementaries” and made no mention of the death-mongering overtones of the ghost-white ship and skeletal figures on board. The critic, in interpreting the vessel either as a “charming toy” or a “floating home of one of the world’s greatest explorers,” further demonstrates how far decolonial thought was from mainstream artistic and art critical discourse.42 More broadly within the cultural field, Indigenous rights activist Charles Perkins resigned from his position on the Captain Cook Bicentenary Celebrations Organising Committee out of protest at the insignificant role of Aboriginal people in the commemorative events.43 Urban practice was similarly insensitive to issues of colonisation. The period witnessed the construction of a public housing estate in Waterloo-Redfern known as the Endeavour project. The tower blocks Marton, Solander, Banks, Turanga and Matavai were named respectively after Cook’s birthplace, two botanists on his voyages and two locations he visited.44 Landmark expressions of anti-colonial activism, such as the Freedom Ride (1965), Harold Thomas’ design of the pan-Aboriginal flag (1971) and the establishment of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy (1972) were therefore still marginal to the concerns of artistic circles of the time.

It is nevertheless tempting to trace in Hinder a manifest humanism, especially in her entry to the 1953 International Sculpture Competition responding to the theme of “the unknown political prisoner.” A highly politicised event taking place during the cultural diplomacy of Cold War tensions, the entry form called for the commemoration of unknown individuals who had sacrificed their lives or liberty for human freedom.45 Art critic Emily Genauer saw no coincidence in the fact that all American pre-finalists were abstractionists, given “artists working in the abstract idiom” were frequently made political prisoners by the dictatorships that the competition was surreptitiously aimed at.46 Promising a monumental site “of world importance, such as a prominent situation in any of the great capitals of the world” the competition attracted thousands of entries.47 The calibre of artists and judges ensured attention from Western media and academia. Hinder finished in the top twelve, at third place, on equal footing with Max Bill, Alexander Calder, Lynn Chadwick, and others. Judges Alfred H. Barr Jr, then director of MoMA, and art critic Herbert Read, awarded Reg Butler first prize, while Naum Gabo and Barbara Hepworth ran equal second.48 Given the spectacular visibility of the International Sculpture Competition, Hinder was likely driven to enter as much by artistic ambition as by any affiliation with the causes espoused by the competition organiser.

Yet there is no denying the political engagement of Hinder and the Sydney modernists she kept in close contact with. Gatherings between Margel, her husband Frank, Gerald and Margot Lewers, Carl Plate, and Jocelyn Zander (later Jocelyn Plate)—dubbed the “Sydney 6”—was often a heated affair. Hinder’s daughter recounted the “excitement of arguments and forthright discussions about art and politics.”49 As World War II began, these artists helped found the Contemporary Art Society of NSW, “driven by a belief that they were living a revolution in the arts.”50 While Margel could not be persuaded to join the Communist Party by its many adherents in the Society, her politics and those of her peers were undoubtedly left-leaning.51 In her own words, “We all were leftist in those days.”52 Her correspondence with politicians through the late 1970s and 1980s show her to be an active lobbyist on animal rights and the natural environment, and reveals a concern for Indigenous rights also. Writing in 1978, Hinder protested Queensland state policy seeking to remove federal protection of Indigenous communities’ right to self-manage. In 1986 and 1987 letters to then prime minister Bob Hawke expressed her “great anger at the sliding of the Labor Party’s Moral Values” on Aboriginal matters and its abandonment of the conservation movement and Indigenous people to gold prospecting by BHP in Kakadu. Identifying as a “very consistent Labor supporter of fifty years,” Margel’s engagement with parliamentary process in Australia hints at a latent patriotism towards her adoptive country.53 Any dismay she experienced at losing US citizenship after voting in the 1941 New South Wales election was outshone by her desire to be Australian: “if you are here, making your living here, bringing your child up here … you should belong to that country.”54

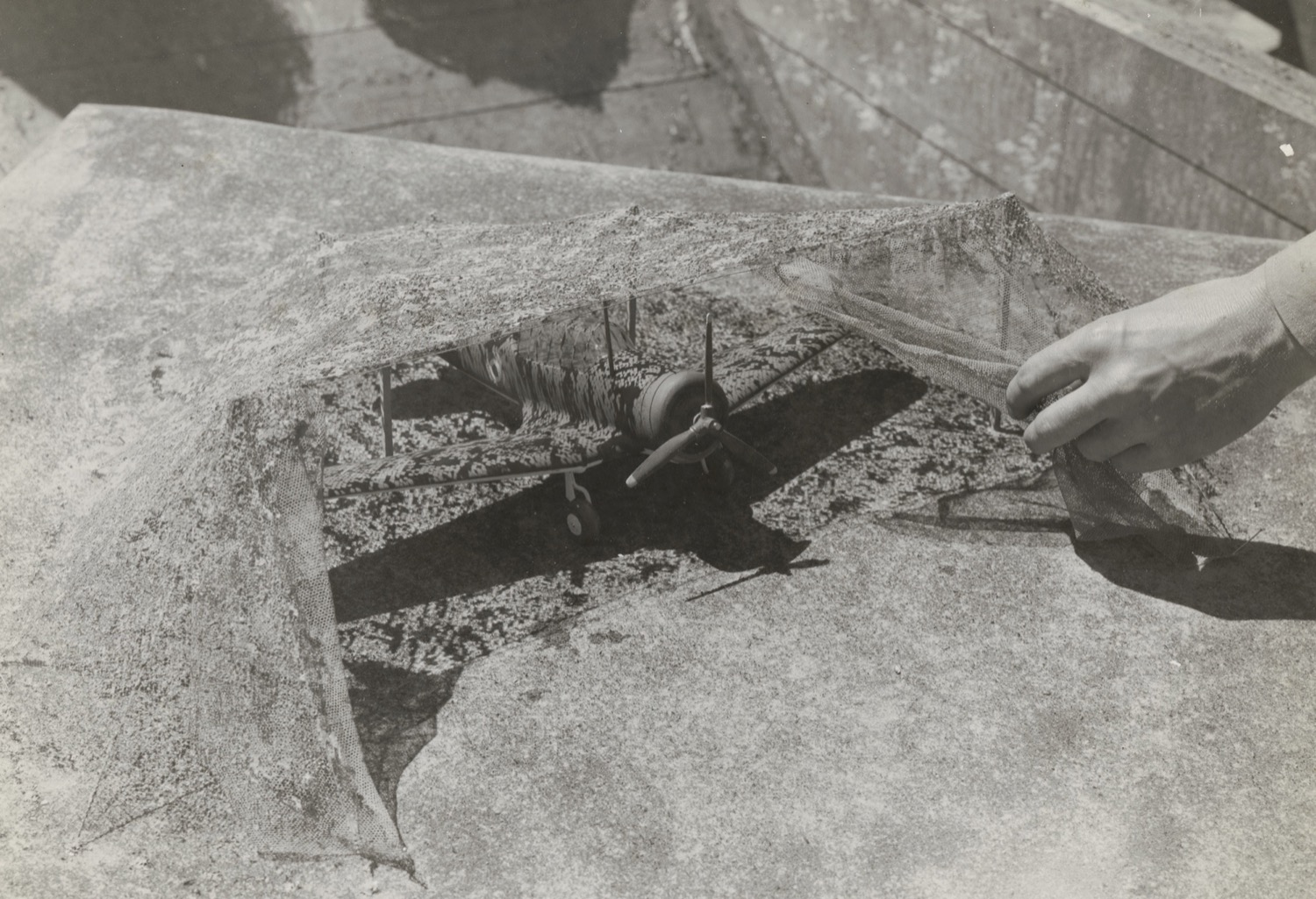

Hinder’s origin as a US citizen was no obstacle to her participation in Australian political life, nor did it impede her full involvement in the defence of her adoptive country from 1939 to 1944. Where Australian-born Margot Lewers objected to military service out of pacifism, Hinder became heavily involved in the war effort. Enamoured by the excitement, adventure, and variety of tasks she was assigned, Hinder would later describe the period as “wonderful” and “lively,” and her uniformed husband as “wonderfully handsome.”55 Through Frank, Margel had close contact with the Sydney Camouflage Group, described by its director as an assembly of “professional workers who have offered their help and are keenly interested” in the role of visual deception in warfare.56 The group was formalised as the Camouflage Research Section of the Department of Home Security, where the Hinders both worked. Margel contributed to the concealment of military assets and critical supplies at strategic sites in Sydney, Newcastle and Port Kembla. She created balsa wood models of aircraft, naval vessels and bulk storage petrol tanks for experiments in visual deception.57 Camouflage techniques were applied to the sculpted miniatures then photographed to judge their efficacy (figs. 11 and 12).

The recruitment of Margel, a sculptor, reflected the fact that camouflage had become less about painted surface and more about three-dimensional structure.58 Art historian Ann Elias notes how modern artists’ command of abstract form and visual trickery made them accomplished camoufleurs, so akin are these strategies to the principles of camouflage. Artists like Hinder possessed a highly trained “facility to turn their knowledge of Abstraction towards Concealment, and their knowledge of Illusionism towards Deception.”59 The utilitarian demands and conservative tastes of the 1940s meant that modernist practice could be recognised as something more than a “useless activity connected with decoration” through its application to the camouflage industry.60 The military service of many twentieth-century abstractionists provides an interesting counterpoint to their progressive politics.

There is a distinct possibility that Hinder’s exposure to the optics, textures, and forms of camouflage and war machinery informed her later practice. Work at the Camouflage Research Section exposed her eye to the deceptive play of light and shadow on the forms she produced. More than cobblers’ tools or rock faces, the robust curvilinear forms of the Hinder fountain are arguably reminiscent of the ships and planes she helped conceal from enemy bombers. In one observer’s fatidic words the sculpture appears as if “the twisted wreckage of a huge burnt-out plane,” a wreck that lies under the current flight path of military aircraft based at nearby Williamtown.61

Where Hinder’s earlier camouflage work deceived airborne foes, her fountain tricks the land-bound passerby not through shadow, colour, or form but nomenclature. This time the subterfuge is practised by concealing the work’s dangerous abstraction under the guise of founding myths of nationhood. It is a colonial tribute that cloaks the monument, and not the mottled surface treatment or the webbed sections resembling the camouflage netting Hinder wove as a civil servant.62 Curiously, at both these points in Hinder’s career—first as camoufleur, then as monumental sculptor—her work is instrumentalised through government commission. Both the camouflage miniatures and the Cook monument defend national sovereignty, whether from the physical threats of Japanese bombers or more discursive challenges from domestic actors. The fountain did this in two important ways for the 1970s public. Firstly, critics of abstract sculpture and government spending on the arts were assuaged by its newly ascribed patriotic function. Secondly, political conservatives and adherents of the “discovery narrative” saw their position bolstered in a period of fervent Indigenous self-affirmation and protest.

War, Colony, and Indigenous Absence

Newcastle memorials show that local commemorative politics stray little from the canon of colonial origins and wartime sacrifice. Civic construction follows a strict calendar marked by dates significant to the national narrative. Newcastle boasts the first soldier statue in Australia, marking the first anniversary of Australian and New Zealand forces landing in Gallipoli, Turkey in 1915.63 A century later in 2015, a lavishly funded “memorial walk” was built skirting the precipice of the city’s highest cliff. Best known as a tribute to Anzac, the monument’s lesser-known function is to celebrate the material history of a former steel-making city. Funded in its majority by mining and manufacturing titan BHP Billiton, the structure is an ode to ferrous matter and industrial might; allusions to military history are superficial by comparison. Silhouettes of soldiers in Corten steel, etched stainless steel panels, and Scrabble-like tiles spelling “A-N-Z-A-C” strike one as decorative afterthoughts intended to imbue an abstract piece of civil engineering with national piety. Official interpretations have taken considerable licence in declaring that the undulating structural design “reflect[s] the double helix of human DNA to identify fallen soldiers on the battlefield of Europe.”64 Like Hinder’s fountain and the War Memorial Cultural Centre, however, the monument’s real interest resides in its formal, spatial, and material qualities; the historical narratives inscribed on all three read like poorly integrated surface scrawl.

The symbolic axis inscribed by Hinder’s fountain and numerous architectural monuments has continued to grow. The addition in 2019 of a life-size bronze figure of former lord mayor Joy Cummings is a welcome, albeit timid, attempt at including women and Indigenous people in the civic pantheon. Completed by Mudgee-based sculptor Margot Stephens, the statue is conceived of as a celebration of Australia’s first female lord mayor and her contributions to reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. What appears to be a purse in the statue’s hand is on closer inspection a folded Aboriginal flag, patinated to evoke the colours red, black, and gold, in reference to Cummings raising the flag over the city hall and bestowing a civic reception in honour of Aboriginal Australians, the first lord mayor to do so.65 Without questioning Cummings’ merits, the statue’s understated approach to historical revision in the pseudo-presence of the flag is flawed in its subtlety. As a proxy for Indigenous people it is semantically camouflaged to the point of invisibility.

Arguably, absence more than presence characterises the Indigenous monument landscape of Newcastle. The missing top half of Whibayganba at the mouth of the harbour—cropped to form what is now Nobbys Head—is emblematic. Further inland, and a short distance from the Cummings statue, stands a similarly sculptural object: the charred remains of an Aboriginal fishing tree significant to the Worimi, whose country spans from the Hunter River through Port Stephens and the Great Lakes. Worimi woman Carol Ridgeway Bissett remembers climbing the tree to watch schools of mullet approaching from upstream. Attacked by arsonists in 2001, the 300 to 400-year-old tree was later felled from its original site near Bagnall’s Beach at the request of Worimi community members and donated to Newcastle Museum for conservation work and custodianship.66 Its truncated form is now compressed between ceiling and floor in the museum foyer. Accompanying information includes a brief description of the footholds that generations of use wore into the trunk. As a monument, the lack of the human figure is palpable, banished from this would-be plinth. The text is both chilling in its assumption of the disappearance of the Worimi people–they “fished”, “made canoes” and “would climb” [author’s emphasis]–and contradictory in affirming that Worimi “have a strong and continuous culture.” Further, the use of the term “vandalised” to describe the tree’s treatment ignores the context of cultural destruction in which the event took place and obfuscates any appraisal of the authors’ intentions as rational or premeditated.67 Vandalism connotes irrational, wanton destruction without ideological motives. It is the wild, program-less and purely delinquent cousin of iconoclasm, which in contrast operates in deliberate and politically motivated ways. To speak of “vandalism” frames the incident as unfortunate, isolated; “iconoclasm” would suggest a more protracted, systematic and collective effort at erasing Aboriginal people and culture.68

Sculptural depictions of Indigenous subjects do exist in the local memorialscape in the virtual reality work Niiarrnumber Burrai (Our Country), though not without irony. Part of a larger project involving the dual-naming of eight significant locations in the Hunter region, content can be accessed by web browser or via an augmented reality app and mobile device.69 By donning a headset or triggering an app, users find Indigenous bodies and knowledges populating an electronically expanded sculptural field. Users are met with virtual environments, animals, objects and Indigenous subjects: Awabakal and Worimi Elders Wayila (Black Cockatoo) and Buuyaan (Bellbird) guide the viewer along placid shores and through the swaying grasses of pre-colonisation.

Yet for all their dynamism these virtual tributes struggle to maintain a purchase on embodied space. The avatars have made less of a mark on the cityscape and the collective imaginary than their physical sculptural counterparts. As a group of electronic experiences, these works are seen only by publics with sufficient interest, technological access, and digital literacy, and therefore remain largely invisible. It is noteworthy that memorials to Indigenous and other underrepresented groups have entered the public realm at a time when the traditional monument is considered by many as anachronistic. The digital turn of many contemporary counter-monumental and anti-memorial strategies raises several questions. Will contemporary sculptural depictions of Australian Aboriginal sovereigns in public space be assimilated into the virtual? How effective a shelter is cyberspace for cultural practice and identity, given its vulnerability to technological obsolescence? Cultural critic Ziauddin Sardar suggested as early as 1995 that the trend towards the digitisation of non-western cultures—their curation in cyberspace—may justify and accelerate their demise in the tangible world.70 No matter how well-intentioned, “extended reality” may in this sense be a new form of cultural erasure.

Whatever the artist’s original designs, Margel Hinder and the Civic Park fountain have become implicated in race politics. Anti-racism campaigners chose the iconic fountain as a backdrop for speakers at a Black Lives Matter protest in June 2020. Evidently, the plaques proclaiming Cook’s discovery did not escape the attention of the public, with one disappearing a month later.71 The second plaque was stolen the following year (fig. 13). This is a curious turn of events for a politically progressive artist who guarded her work from misattributions of meaning. Hinder’s supremely political gesture as an artist was to announce that her abstract work “represents nothing” and in doing so deny the object any function as a vehicle for ideology. She opposed the use of her Woden sculpture as a surface for posters during the “Free Baba” campaign by religious group Ananda Marga, and reluctantly acknowledged that public sculpture “might possibly have to provide a platform” for political rallies.72

As problematic as the semantic transformation of the fountain is, it would be simplistic to conclude that the name of James Cook politicised an otherwise apolitical monument. In 1966 the abstract sculpture already worked to promote an image of civic and cultural progress in line with local government policy. By the same token, positioning the artist as an innocent bystander to the instrumentalisation of her work would be disingenuous. We might venture that, while Hinder exercised great control over the formal and technical aspects of her work, she was cognisant that the meaning of a commissioned piece is not always “the product of a mutual understanding between artist and patron”—much less the exclusive domain of the artist—but that the patron may sometimes resignify the work unilaterally.73 Hinder was after all no stranger to politics and its relationship with art. Indeed, a reliance on institutional patronage has made ideological flexibility a hallmark of monumental sculptors.74 For Hinder the effort paid off. In 1979 after decades of courting government favour, Margel was awarded the Australia Medal for her artistic contributions, the Civic Park fountain widely recognised as her crowning achievement. Such an account of Hinder’s professional activities contrasts with the well-rehearsed narrative of a left-leaning internationalist pitted against the aesthetic parochialism of a culturally conservative and nationalistic Australia. Far from the innocent and naive “sculptress,” Hinder’s actions are those of a pragmatist rather than an idealist. She appears to accept that, in return for the possibility of realising her creative vision, her work will be co-opted by the bodies that fund it, curate its display, and choose to conserve or neglect it. Nowhere is this more evident than in the successive “dual-naming” of her fountain’s deceptive title.

-

See Lesley Harding and Denise Mimmocchi, eds., Margel Hinder: Modern in Motion (Sydney and Melbourne: Art Gallery of New South Wales and Heide Museum of Modern Art, 2021). ↩

-

The second plaque has since been removed in what appears to be a second iconoclastic act. The first published account appears to be the author’s own on 6 May 2021 at https://twitter.com/nikolas_orr/status/1390245309196816385. ↩

-

Newcastle City Council, “Conditions of Competition for Design of a Fountain in Civic Park, Newcastle, NSW,” 1961, held in State Library of New South Wales, MLMSS 6088 “Margel Hinder Papers, ca.1900–1995.” ↩

-

Daniel J. Sherman, “Art, Commerce, and the Production of Memory in France after World War I,” in Commemorations: The Politics of National Identity, ed. John R. Gillis (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), 203. ↩

-

Newcastle Art Gallery, “About the Gallery,” accessed 13 November 2020. https://newcastle-collections.ncc.nsw.gov.au/gallery?page=about. ↩

-

Scott Morrison and Darren Chester, “Telling the Stories of Our Service Men and Women,” (Australian War Memorial, 1 November 2018). https://www.awm.gov.au/media/press-releases/telling-the-stories. ↩

-

Rhonda Jolly, “Arts and Culture,” Budget Review 2017–18, Parliament of Australia, 2017. https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/BudgetReview201718/Arts#\_ftn15. ↩

-

Desmond Manderson in Hilary Charlesworth, Desmond Manderson, and Julie Gough, In Politics and Law, Does Art Matter?, podcast, Big Ideas, 2020, https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/bigideas/art,-law-and-politics/11670728. ↩

-

See assessor’s report dated September 1961 in State Library of New South Wales, MLMSS 6088, Box 1. ↩

-

“Our Public Art: James Cook Fountain,” Newcastle Herald, 24 January 2014; Mike Scanlon, “Margel Hinder’s Design Survived Many Suggestions,” Newcastle Herald, 2017. https://www.newcastleherald.com.au/story/4594143/the-painful-birth-of-civic-park-fountain/. ↩

-

Margel Hinder, Competition for the Design of a Fountain in Civic Park, Newcastle, NSW: Copy of Report Submitted by Author of Design No. 24 (September 1961), unpublished. Located at Art Gallery of New South Wales Research Library and Archive, MS1995.2 “Papers of Margel Hinder,” Folder 11 “Work 1961–62” (M78), ARC322.78.2. ↩

-

Margel Hinder, “Fountain That Will Read As Sculpture,” Newcastle Herald, 3 October 1966, quoted by curator Sarah Johnson in Newcastle Art Gallery, Sydney 6: Hinders, Lewers, Plates: Abstract Artists, Friends, Partners, Siblings, 1940s–1970s (Newcastle: Newcastle Art Gallery, 2015). http://www.nag.org.au/getattachment/Exhibitions/Current/Archives/2015/SYDNEY-6-Hinders-Lewers-Plates-Abstract-artists,/Sydney_6_catalogue_pageview_SML.pdf.aspx. ↩

-

Larissa Smagarinsky, Gaye Evans, and Margel Hinder, “Three Australian Woman Sculptors,” Transforming: Art 3, no. 2 (1989): 19. ↩

-

Norm Barney, “New Fountain Made a Splash,” Newcastle Herald, 3 September 1994; Unidentified interview in State Library of New South Wales, MLMSS 6088, Box 8. ↩

-

Renée Free, Frank and Margel Hinder 1930–1980 (Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 1980), 55; referred to again in Ian Cornford, The Sculpture of Margel Hinder (Willoughby: Phillip Mathews, 2013), 119. ↩

-

Smagarinsky, Evans, and Hinder, “Three Australian Woman Sculptors,” 19. ↩

-

In 1953 Hinder definitively swapped wood for metal as her preferred medium, opening the way to outdoor sculpture. For a catalogue raisonée of her work, see David Thomas’ exhibition catalogue, Frank and Margel Hinder Retrospective (Newcastle: Newcastle City Art Gallery, 1973) and Free, Frank and Margel Hinder 1930–1980. ↩

-

Dinah Dysart, Frank Hinder, and Margel Hinder, “A Productive Partnership: Frank and Margel Hinder Interviewed,” Art and Australia 29, no. 3 (Autumn 1992): 344. ↩

-

Cornford, The Sculpture of Margel Hinder, 119. ↩

-

Barney, “New Fountain Made a Splash.” ↩

-

Bernard Smith, “The Antipodean Manifesto: Essays in Art and Art History,” Leonardo 13, no. 1 (1980): 87, https://doi.org/10.2307/1577968. ↩

-

Matt Hayes, “Bird or Beast … Or Outsize Boot Last?,” Newcastle Sun, 26 July 1966, Point of View; “City Gets Its ‘Pile of Junk’,” Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 2 November 1966. ↩

-

Smith, “The Antipodean Manifesto: Essays in Art and Art History,” 87. ↩

-

Newcastle Art Gallery, “About the Gallery.” ↩

-

Christine France, “A Total Creative Force: The ‘Sydney 6’,” Art Monthly Australasia, no. 280 (2015): 31. ↩

-

Attacks on abstraction in public sculpture are by no means limited to regional Australia nor to the early-to-mid-century period. The defacement and removal of Ron Robertson-Swann’s Vault took place in urbane 1980s Melbourne. ↩

-

See Art Gallery of New South Wales Research Library and Archive, MS1995.1 “Papers of Frank Hinder.” ↩

-

Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 6, 210. ↩

-

Correspondence from Margel Hinder to William Burges dated 2 May and 29 June 1966, held at State Library of New South Wales, MLMSS 6088, Box 1. ↩

-

“Fairer Fountain as Memorial,” Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 29 April 1970, 1, 23. ↩

-

Author’s translation from Rodrigo Gutiérrez Viñuales, Monumento conmemorativo y espacio público en Iberoamérica (Madrid: Cátedra, 2004), 163. ↩

-

Civic Park attendance numbered 15,000 according to “Stroll Through Civic Park Delights People,” Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 11 April 1970, 1. ↩

-

Cornford, The Sculpture of Margel Hinder, 134. ↩

-

Thomas, Frank and Margel Hinder Retrospective. ↩

-

Free’s texts include Frank and Margel Hinder 1930–1980; “The Art of Frank and Margel Hinder, 1930–1980,” Art and Australia 18, no. 3 (1981); “Hinder Family,” Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online, updated 1 December 2004; see also Luke Morgan, “Abstract Fountains,” in Modern Times: The Untold Story of Modernism in Australia, ed. Ann Stephen, Philip Goad, and Andrew McNamara (Carlton: Miegunyah Press, 2008), 41. ↩

-

Cornford, The Sculpture of Margel Hinder, 123. ↩

-

Cassi Plate, “An Untold Story: How Three Artistic Couples Became the ‘Sydney 6’,” Exhibition review, Art Monthly Australasia, no. 280 (2015); Harding and Mimmocchi (eds.), Margel Hinder: Modern in Motion. ↩

-

Kiera Lindsey et al., “Statue Wars (1)–Vandalism or Vindication and What to Do with the Empty Plinth,” in History Now (History Council of New South Wales, 13 September 2020). https://youtu.be/1Iir4UL2Voo; Michael Parris, “Call to Remove Captain Cook Plaques Over ‘Offensive’ Text,” Newcastle Herald, 20 July 2020, https://www.newcastleherald.com.au/story/6840443/call-to-remove-captain-cook-plaques-over-offensive-text/; Michael Parris, “Newcastle Council Reviews Captain Cook Plaques in Civic Park,” Newcastle Herald, 29 July 2020, https://www.newcastleherald.com.au/story/6854852/newcastle-council-reviews-captain-cook-plaques/; City of Newcastle, “Ordinary Council Meeting,” updated 28 July, 2020, https://newcastle.nsw.gov.au/council/news/latest-news/council-update-ordinary-council-meeting-tuesday-28. ↩

-

Evidently, Hinder felt a greater threat to her moral rights in the local government’s decision in 1973 to illuminate the fountain with green light, which she fought successfully via legal action. Were Hinder to have felt similarly about the fountain’s name, she would have found little consolation in Australian copyright law, which like most modern legal systems does not protect names or titles. See Australian Copyright Council, “Australian Copyright Council,” 2020, https://www.copyright.org.au/; Ruth Bernard Yeazell, Picture Titles: How and Why Western Paintings Acquired Their Names (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), 81. ↩

-

In a letter dated 7 April, Margel Hinder replies only to the “lamp standards at the bottom of the steps” and additional step lights, which she foresees will “negate the fountain lighting.” See State Library of New South Wales, MLMSS 6088, Box 1. ↩

-

Alan McCulloch, “Letter from Australia,” Art International 14, no. 10 (1970): 41. ↩

-

McCulloch, “Letter from Australia,” 42–43. ↩

-

“Perkins Resigns Cook Committee,” Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 3 May 1969. ↩

-

Mayane Dore, “Waterloo-Redfern and the Racism Rooted in Cities,” Sapiens, 15 September 2020, https://www.sapiens.org/culture/waterloo-redfern-housing/; James Cunningham, “As It Happened: The Queen Opens Waterloo Towers,” Sydney Morning Herald, 4 December 2017, https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/as-it-happened-the-queen-opens-waterloo-towers-20170412-gvjksz.html. ↩

-

Alex J. Taylor, “Cold War Diplomacy,” In Focus: The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) 1952 (London: Tate Research Publication, 2018), https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/in-focus/unknown-political-prisoner/cold-war-diplomacy. ↩

-

Emily Genauer, “Art and Artists: Sculptors Chided for Conceiving Political Prisoner as Abstraction,” New York Herald Tribune, 1 February 1952, 10, cited in Taylor, “Cold War Diplomacy.” ↩

-

The Unknown Political Prisoner competition entry form, Tate Archive TGA 955/1/12/256, cited in Helen Little and Arthur Goodwin, “Reg Butler: Final Maquette for ‘The Unknown Political Prisoner’ 1951–2,” Art & Artists, Tate, updated December 2018, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/butler-final-maquette-for-the-unknown-political-prisoner-l01102. ↩

-

Cornford, The Sculpture of Margel Hinder, 85–86. ↩

-

Quoted in Plate, “An Untold Story: How Three Artistic Couples Became the ‘Sydney 6’,” 33. ↩

-

Denise Mary Whitehouse, “The Contemporary Art Society of NSW and the Theory and Production of Contemporary Abstraction in Australia, 1947–1961” (Doctor of Philosophy, Monash University, 1999), 37–38. ↩

-

Margel Hinder, “Interview of Margel Hinder,” interview by Hilary McPhee and Drusilla Modjeska, 13 August 1993 as transcribed in State Library of New South Wales, MLMSS 6088, Box 8. A full recording is available at National Library of Australia, https://nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn2939743. ↩

-

Dysart, Hinder, and Hinder, “A Productive Partnership: Frank and Margel Hinder Interviewed,” 341. ↩

-

Correspondence located at State Library of New South Wales, MLMSS 6088, Box 5. ↩

-

Letters between Hinder and US consul Charles H. Derry, 5 August to 4 November 1942, located at State Library of New South Wales, MLMSS 6088, Box 8; Hinder, interview by McPhee and Modjeska. ↩

-

Hinder, interview by McPhee and Modjeska. ↩

-

Ann Elias, “The Organisation of Camouflage in Australia in the Second World War,” Journal of the Australian War Memorial, no. 38 (2003): para. 5, 7, https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/journal/j38/camouflage. ↩

-

Elias mentions only bulk fuel deposits in “The Organisation of Camouflage in Australia in the Second World War,” para. 12, whereas ship and plane models are referenced by Margel in several manuscripts in State Library of New South Wales, MLMSS 6088, Box 8, and by Eileen Chanin, “Hinder, Margel Ina (1906–1995),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, 2016, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hinder-margel-ina-18079/text29445. ↩

-

Elias, “The Organisation of Camouflage in Australia in the Second World War,” para. 6. ↩

-

Elias, “The Organisation of Camouflage in Australia in the Second World War,” para. 9. ↩

-

Elias, “The Organisation of Camouflage in Australia in the Second World War,” para. 10. ↩

-

Scanlon, “Margel Hinder’s Design Survived Many Suggestions.” ↩

-

Hinder, interview by McPhee and Modjeska. ↩

-

Only its foundation stone was laid in time for the first anniversary of the Anzac landing, 25 April 1916. Returned servicemen saluted an empty plinth. The statue—a proxy for the missing dead—had not yet shipped for Australia from Italy. See Kenneth Stanley Inglis and Jan Brazier, “The Great War,” in Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape (Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 2005), 75, 100; also New South Wales Government, “Newcastle First World War Memorial,” New South Wales War Memorial Register, n.d., accessed 24 October 2020, https://www.warmemorialsregister.nsw.gov.au/memorials/newcastle-first-world-war-memorial. ↩

-

Northrop, “Newcastle Memorial Walk,” n.d., accessed 21 October 2020, https://northrop.com.au/project/newcastle-memorial-walk. ↩

-

uoncc, “Joy Cummings–“Words Were Not Important – Love Has Its Own Language”–A Tribute to Australia’s First Female Lord Mayor,” Hunter Living Histories, University of Newcastle, updated 18 January, https://hunterlivinghistories.com/2019/01/18/joy-cummings/. ↩

-

Viola Brown et al., Aboriginal Women’s Heritage: Port Stephens, ed. Kath Schilling (NSW: Department of Environment and Conservation, 2004), 42. ↩

-

Newcastle Museum, “Fishing Tree,” n.d., accessed 21 October 2020, https://www.newcastlemuseum.com.au/collection/highlights/fishing-tree. ↩

-

For an extended critique of the popular distinction between vandalism and iconoclasm see David Freedberg, The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989); and Dario Gamboni, The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism Since the French Revolution (London: Reaktion, 1997). ↩

-

City of Newcastle, “Niiarrnumber Burrai (Our Country) – Newcastle VR,” (8 July, 2018). https://youtu.be/fbMqrQd2FsI. ↩

-

Ziauddin Sardar, “alt.civilizations.faq: Cyberspace as the Darker Side of the West,” Futures 27, no. 7 (1995). ↩

-

Parris, “Call to Remove Captain Cook Plaques Over ‘Offensive’ Text.” ↩

-

Unidentified interview in State Library of New South Wales, MLMSS 6088, Box 8. ↩

-

Yeazell, Picture Titles: How and Why Western Paintings Acquired Their Names, 20. ↩

-

One of countless such examples is the Spanish artist Juan de Avalós (1911–2006), responsible for the key sculptural elements of the emblematic Francoist monument, El Valle de los Caídos (Valley of the Fallen). De Avalós was, in the years immediately after the Spanish Civil War, prohibited from executing state-funded projects or occupying official positions due to his earlier affiliation with the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party. In 1950, however, he accepted an invitation from the regime to submit an entry to a closed competition for the ornamentation of El Valle de los Caídos. See “Biografía cronológica de Juan de Avalós,” Fundación Juan de Avalós, n.d., accessed 4 November 2020, http://www.fundacionjuandeavalos.es/biografia.htm. ↩

NIKOLAS ORR is a 2020–2021 Gowrie scholar and PhD (History) candidate at the Centre for Studies of Violence, University of Newcastle, Australia. He has held various teaching and research roles in the School of Creative Industries, School of Humanities and Social Science, and Newcastle Law School of the same institution since 2018. Nikolas graduated with first-class honours and distinction respectively from a Bachelor of Fine Arts (Sculpture) at University of Sydney and a Masters in Contemporary Art History and Visual Culture at Universidad Autónoma de Madrid and Universidad Complutense de Madrid. He is currently conducting research into contemporary anti-colonial iconoclasm with a transnational perspective on former British and Spanish colonies especially.

Email: nik.orr@newcastle.edu.au

Twitter: @nikolas_orr

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3371-7871

The author acknowledges Dr Una Rey for her deft edits and insightful suggestions that lent much art-historical depth to the article, Gionni DiGravio for his help in mapping the evolution of Civic Park, and the librarians at Newcastle Region Library, State Library of New South Wales, and Art Gallery of New South Wales Research Library and Archive.

Bibliography

- Art Gallery of New South Wales Research Library and Archive. MS1995.1 “Papers of Frank Hinder”.

- Art Gallery of New South Wales Research Library and Archive. MS1995.2 “Papers of Margel Hinder.”

- Australian Copyright Council. “Australian Copyright Council.” 2020. https://www.copyright.org.au/.

- Barney, Norm. “New Fountain Made a Splash.” Newcastle Herald, 3 September 1994.

- “Biografía cronológica de Juan de Avalós.” Fundación Juan de Avalós, n.d., accessed 4 November 2020. http://www.fundacionjuandeavalos.es/biografia.htm.

- Brown, Viola, Beverley Manton, Val Merrick, Colleen Perry, Carol Ridgeway Bisset, and Gwen Russell. Aboriginal Women’s Heritage: Port Stephens, edited by Kath Schilling. NSW: Department of Environment and Conservation, 2004.

- Chanin, Eileen, “Hinder, Margel Ina (1906–1995).” Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography. Canberra: Australian National University, 2016. http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hinder-margel-ina-18079/text29445.

- Charlesworth, Hilary, Desmond Manderson, and Julie Gough. In Politics and Law, Does Art Matter? Podcast. Big Ideas, 2020. https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/bigideas/art,-law-and-politics/11670728.

- “City Gets Its ‘Pile of Junk’,” Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 2 November 1966.

- City of Newcastle. “Niiarrnumber Burrai (Our Country) – Newcastle VR.” 8 July 2018. https://youtu.be/fbMqrQd2FsI.

- City of Newcastle. “Ordinary Council Meeting,” updated 28 July 2020. https://newcastle.nsw.gov.au/council/news/latest-news/council-update-ordinary-council-meeting-tuesday-28.

- Cornford, Ian. The Sculpture of Margel Hinder. Willoughby: Phillip Mathews, 2013.

- Cunningham, James. “As It Happened: The Queen Opens Waterloo Towers.” Sydney Morning Herald, 4 December 2017. https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/as-it-happened-the-queen-opens-waterloo-towers-20170412-gvjksz.html.

- Dore, Mayane. “Waterloo-Redfern and the Racism Rooted in Cities.” Sapiens, 15 September 2020.

https://www.sapiens.org/culture/waterloo-redfern-housing/. - Dysart, Dinah, Frank Hinder, and Margel Hinder. “A Productive Partnership: Frank and Margel Hinder Interviewed.” Art and Australia 29, no. 3 (Autumn 1992): 338–45.

- Elias, Ann. “The Organisation of Camouflage in Australia in the Second World War.” Journal of the Australian War Memorial, no. 38 (2003). https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/journal/j38/camouflage.

- “Fairer Fountain as Memorial.” Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 29 April 1970, 1, 23.

- France, Christine. “A Total Creative Force: The ‘Sydney 6’.” Exhibition Review. Art Monthly Australasia, no. 280 (2015): 30–31.

- Free, Renée. “The Art of Frank and Margel Hinder, 1930–1980.” Art and Australia 18, no. 3 (1981): 241–48.

- Free, Renée. Frank and Margel Hinder 1930–1980. Exhibition catalogue. Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 1980.

- Free, Renée. “Hinder Family.” Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online, updated 1 December 2004.

- Freedberg, David. The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989.

- Gamboni, Dario. The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism Since the French Revolution. London: Reaktion, 1997.

- Gutiérrez Viñuales, Rodrigo. Monumento conmemorativo y espacio público en Iberoamérica. Madrid: Cátedra, 2004.

- Harding, Lesley, and Denise Mimmocchi, eds. Margel Hinder: Modern in Motion. Exhibition Catalogue. Sydney and Melbourne: Art Gallery of New South Wales and Heide Museum of Modern Art, 2021.

- Hayes, Matt. “Bird or Beast … Or Outsize Boot Last?” Newcastle Sun, 26 July 1966.

- Hinder, Margel. “Interview of Margel Hinder.” By Hilary McPhee and Drusilla Modjeska, 13 August 1993.

- Inglis, Kenneth Stanley, and Jan Brazier. “The Great War.” In Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, 75–122. Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 2005.

- Jolly, Rhonda, “Arts and Culture.” Budget Review 2017–18. Parliament of Australia, 2017. https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/BudgetReview201718/Arts#\_ftn15.

- Lindsey, Kiera, Nathan Mudyi Sentance, Jess Moody, Claire Baxter, and Christer Petley. “Statue Wars (1) – Vandalism or Vindication and What to Do with the Empty Plinth.” In History Now, History Council of New South Wales, 13 September 2020. https://youtu.be/1Iir4UL2Voo.

- Little, Helen, and Arthur Goodwin. “Reg Butler: Final Maquette for ‘The Unknown Political Prisoner’ 1951–2.” Art & Artists, Tate, updated December 2018. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/butler-final-maquette-for-the-unknown-political-prisoner-l01102.

- McCulloch, Alan. “Letter from Australia.” Art International 14, no. 10 (1970): 40–45.

- Morgan, Luke. “Abstract Fountains.” In Modern Times: The Untold Story of Modernism in Australia, edited by Ann Stephen, Philip Goad and Andrew McNamara, 36–41. Carlton: Miegunyah Press, 2008.

- Morrison, Scott, and Darren Chester. “Telling the Stories of Our Service Men and Women.” Media Statement. Australian War Memorial, 1 November 2018. https://www.awm.gov.au/media/press-releases/telling-the-stories.

- New South Wales Government. “Newcastle First World War Memorial.” New South Wales War Memorial Register, n.d., accessed 24 October 2020. https://www.warmemorialsregister.nsw.gov.au/memorials/newcastle-first-world-war-memorial.

- Newcastle Art Gallery. “About the Gallery,” n.d., accessed 13 November 2020. https://newcastle-collections.ncc.nsw.gov.au/gallery?page=about.

- Newcastle Art Gallery. Sydney 6: Hinders, Lewers, Plates: Abstract Artists, Friends, Partners, Siblings, 1940s–1970s. Exhibition catalogue. Newcastle: Newcastle Art Gallery, 2015. http://www.nag.org.au/getattachment/Exhibitions/Current/Archives/2015/SYDNEY-6-Hinders-Lewers-Plates-Abstract-artists,/Sydney_6_catalogue_pageview_SML.pdf.aspx

- Newcastle Museum. “Fishing Tree,” n.d., accessed 21 October 2020. https://www.newcastlemuseum.com.au/collection/highlights/fishing-tree.

- Northrop. “Newcastle Memorial Walk,” n.d., accessed 21 October 2020. https://northrop.com.au/project/newcastle-memorial-walk.

- “Our Public Art: James Cook Fountain.” Newcastle Herald, 24 January 2014, 48.

- Parris, Michael. “Call to Remove Captain Cook Plaques Over ‘Offensive’ Text.” Newcastle Herald, 20 July 2020. https://www.newcastleherald.com.au/story/6840443/call-to-remove-captain-cook-plaques-over-offensive-text/.

- Parris, Michael. “Newcastle Council Reviews Captain Cook Plaques in Civic Park.” Newcastle Herald, 29 July 2020. https://www.newcastleherald.com.au/story/6854852/newcastle-council-reviews-captain-cook-plaques/.

- “Perkins Resigns Cook Committee.” Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 3 May 1969, 31.

- Plate, Cassi. “An Untold Story: How Three Artistic Couples Became the ‘Sydney 6’.” Exhibition review. Art Monthly Australasia, no. 280 (2015): 32–33.

- Sardar, Ziauddin. “alt.civilizations.faq: Cyberspace as the Darker Side of the West.” Futures 27, no. 7 (1995): 777–94.

- Savage, Kirk. Standing soldiers, kneeling slaves: Race, war, and monument in nineteenth-century America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997.

- Scanlon, Mike. “Margel Hinder’s Design Survived Many Suggestions.” Newcastle Herald, 2017. https://www.newcastleherald.com.au/story/4594143/the-painful-birth-of-civic-park-fountain/.

- Sherman, Daniel J. “Art, Commerce, and the Production of Memory in France after World War I.” In Commemorations: The Politics of National Identity, edited by John R. Gillis, 186–211. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994.

- Smagarinsky, Larissa, Gaye Evans, and Margel Hinder. “Three Australian Woman Sculptors.” Transforming: Art 3, no. 2 (1989): 15–20.

- Smith, Bernard. “The Antipodean Manifesto: Essays in Art and Art History.” Leonardo 13, no. 1 (1980): 87. https://doi.org/10.2307/1577968.

- State Library of New South Wales. MLMSS 6088 “Margel Hinder Papers, ca.1900–1995”.

- “Stroll Through Civic Park Delights People.” Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 11 April 1970, 1, 3.

- Suters, Brian. “Fountain Artist Would Not Change Her Mind.” Newcastle Herald, 25 August 2018, 30. https://www.newcastleherald.com.au/story/5606191/letters-fountain-artist-would-not-change-her-mind/.

- Taylor, Alex J., “Cold War Diplomacy.” In Focus: The Unknown Political Prisoner (Defiant and Triumphant) 1952. London: Tate Research Publication, 2018. https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/in-focus/unknown-political-prisoner/cold-war-diplomacy.

- Thomas, David. Frank and Margel Hinder Retrospective. Exhibition catalogue. Newcastle: Newcastle City Art Gallery, 1973.

- uoncc, “Joy Cummings—“Words Were Not Important – Love Has Its Own Language”—A Tribute to Australia’s First Female Lord Mayor.” Hunter Living Histories, University of Newcastle, updated 18 January. https://hunterlivinghistories.com/2019/01/18/joy-cummings/.

- Whitehouse, Denise Mary. “The Contemporary Art Society of NSW and the Theory and Production of Contemporary Abstraction in Australia, 1947–1961.” Doctor of Philosophy, Monash University, 1999.

- Yeazell, Ruth Bernard. Picture Titles: How and Why Western Paintings Acquired Their Names. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.