Time, After Time Or How to Work with History

That journey into the desert that you’d spoken of, you will take it alone?1

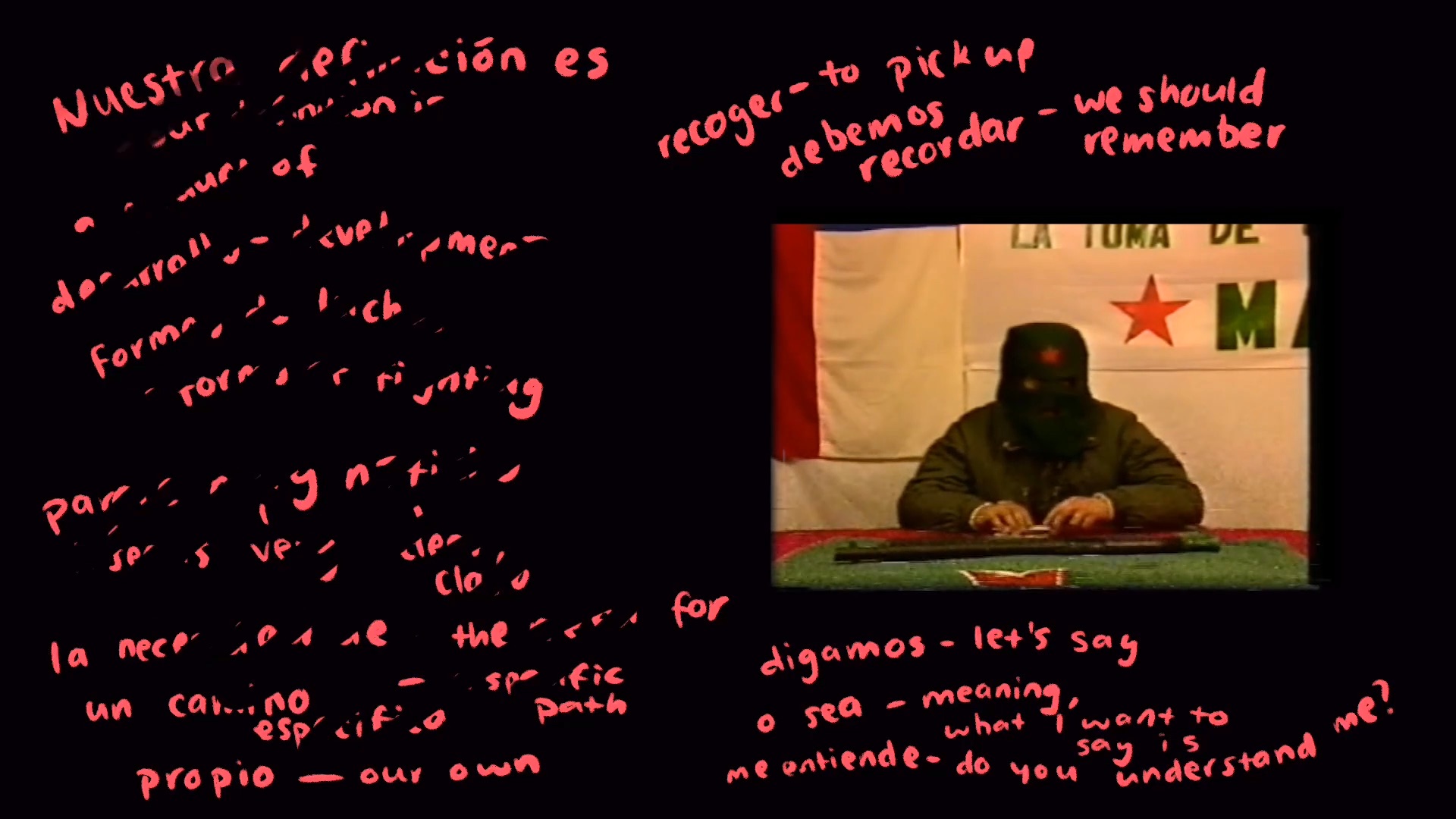

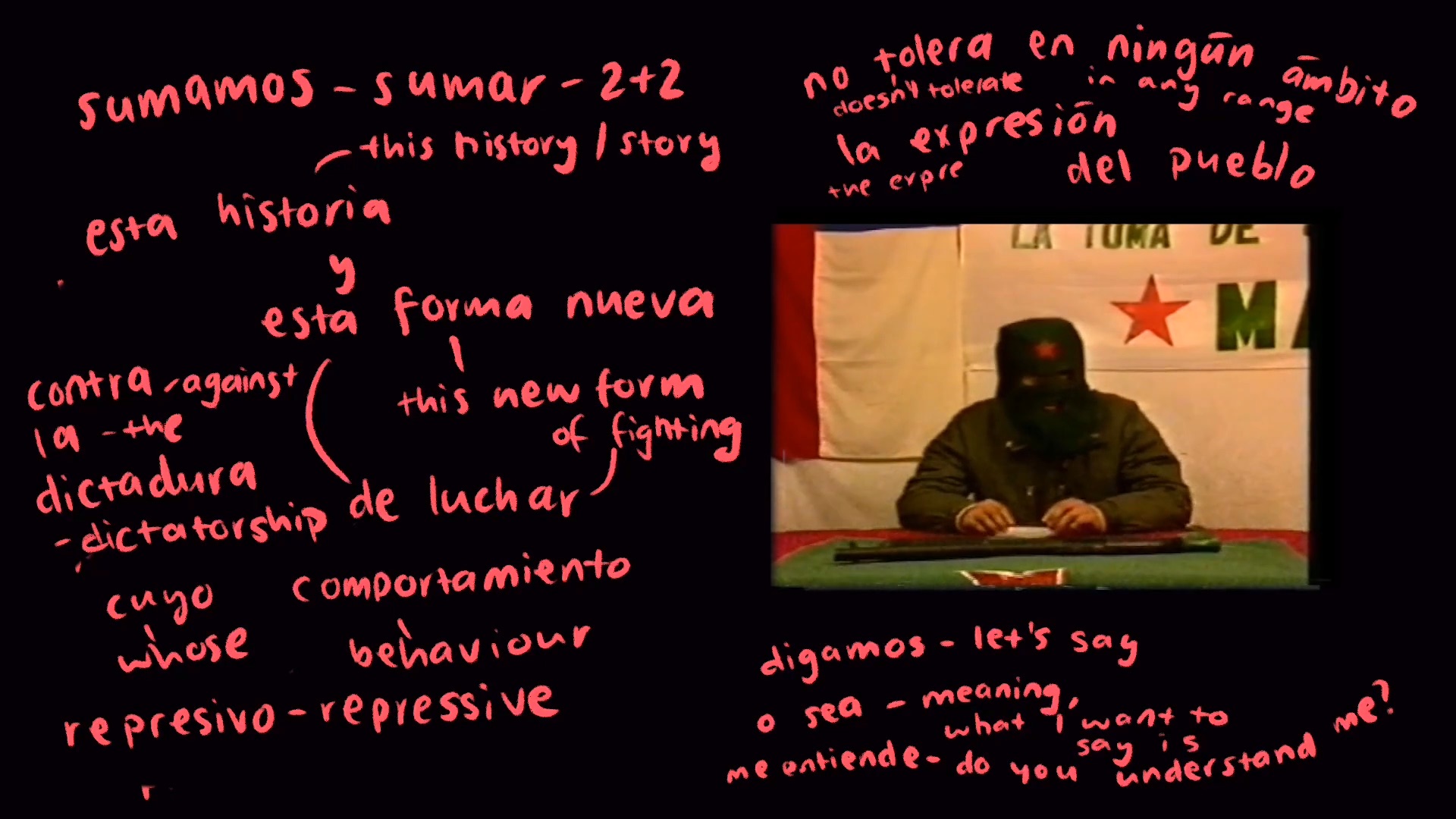

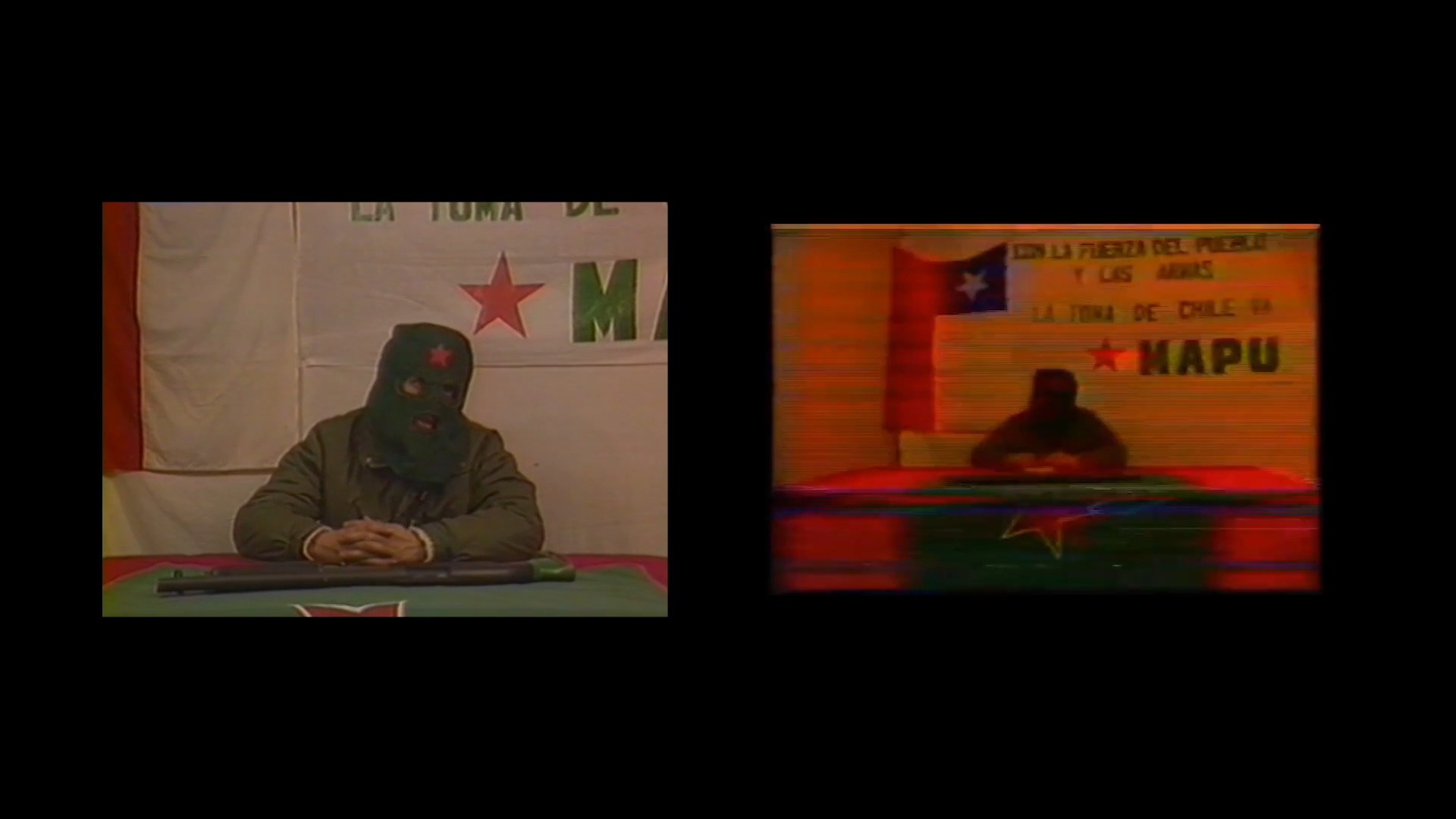

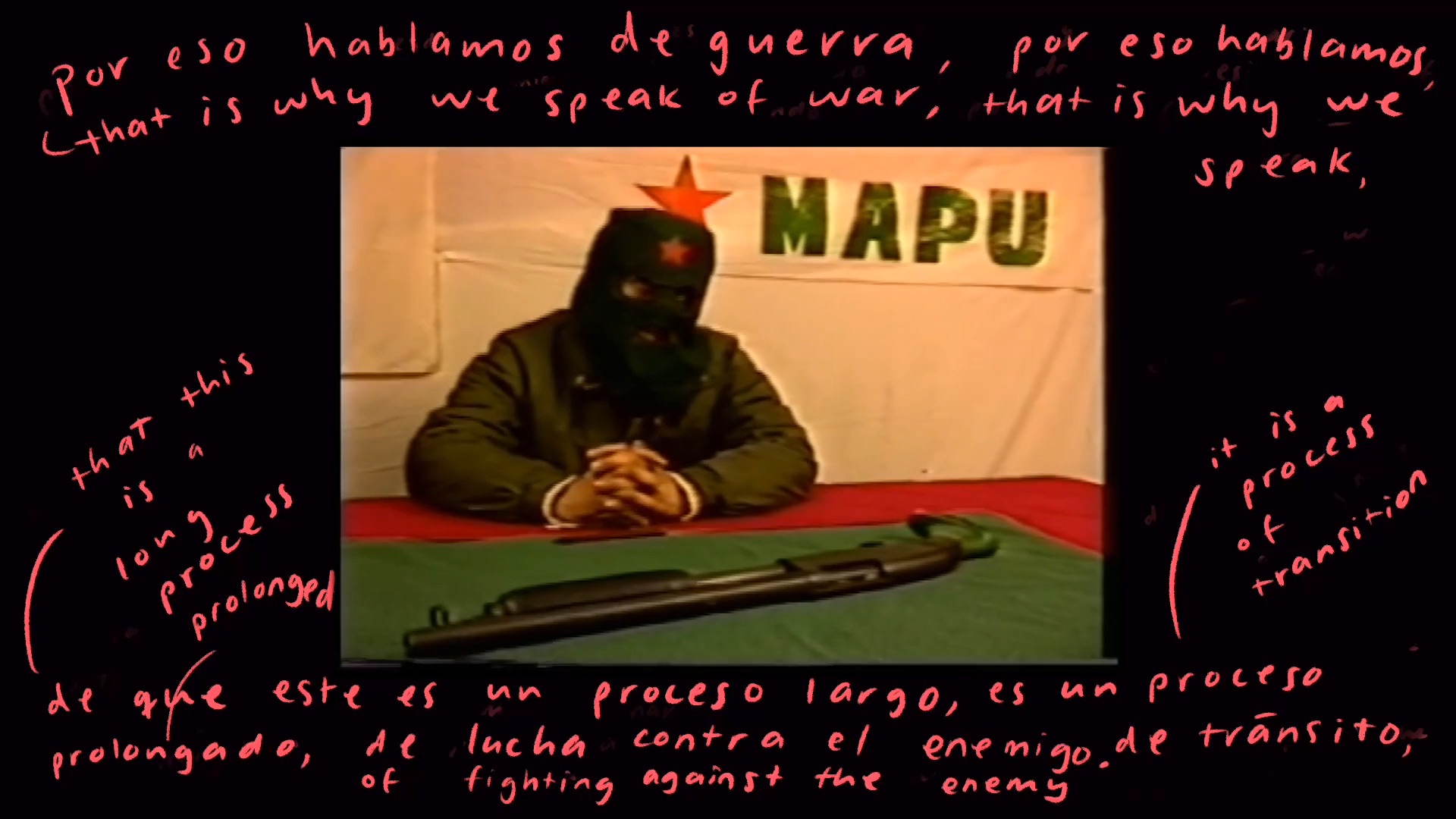

In 2019, I worked on a video project titled Vecino Vecino. It was a 20-minute, single-channel documentary that unpacked a French news segment from 1986 portraying an armed resistance group, The Lautaro Youth Movement or MAPU-Lautaro in Chile, to whom my forbearers were connected.2 As a second-generation Chilean-Australian living in exile, I was drawn to the news segment for its content. However, this information was hidden behind layers of language, performance (for the camera and the self), subjective storytelling, and nationalist agendas. As an artist and a researcher, I was interested in how we understand and process history and how shifting these ideas can change our perceptions of the present and ourselves. Throughout Vecino Vecino, I examined the media’s content and archival forms, highlighting the ongoing rifts caused by state violence.3

While developing Vecino Vecino, I devised the syllabus for Time, After Time: a re-performance workshop—a workshop and lecture series produced by Free Association for the Channels Festival: International Biennial of Video Art 2019.4 The workshop had an eight-person cohort, and each participant brought a historical document, an object, or a story as a springboard for making. The workshop ran for three weeks and ultimately culminated in a public presentation. Sessions were divided into lectures, discussions, and “crits,” where participants were supported to develop new works, drawing on the same methodology for making but eventuating differing forms. Some of these works were intimate and familial stories, while others were connected to threads within the participants’ practices. Some participants were finding new directions for themselves, and others were continuing projects already underway. All the works developed in the workshop were smaller components of larger research and studio-based projects—works within themselves and gestures towards broader ideas. I use the term “re-performance” within my practice as a container for various ways to work with historical events and documents. Rather than simply being a re-enactment of exact events, I view re-performance as a more fluid and malleable process.

History is known and understood through representation. It is understood through historical documentation and contemporary interpretation. Re-performance within contemporary art affords inquiry into the content and context of history. It offers the opportunity to construct alternative forms of memory. Here, I have revisited and edited my 2019 lectures, which are reprinted in the following pages—a re-performance in themselves. Although the years have passed since I delivered these lectures, I maintain that artists can use re-performance as a valuable tool for assessing history, promoting historical and media literacy, and telling complex personal stories. The following lectures guide artists and outline my thinking on how re-performance can be used within contemporary art—forged through my own artistic practice and research. The lectures look at how and why re-performance is used in artworks, outline steps towards creating work, and discuss approaches to ethical considerations.

I had been working with re-performance as a tool in my practice for several years: scripting and copying the movements of stand-up comedians in I want to discover my masterpiece right now and I want them to see it (2007), spontaneous gestures of mimicry in Let’s Defo hang out in Melbz (2007), and the re-performance of films and books such as Crocodile Dundee (1986) (Dead End. Brilliant., 2020) and Albert Camus’ The Plague (1947) (Unwelcome Visitant, 2020). I have worked with the term “re-performance” over the term “re-enactment” as I believe it holds more space for interpretation and transmutation rather than exact reproduction. If re-enactment is a method, re-performance is a tool to work with the material of history.5

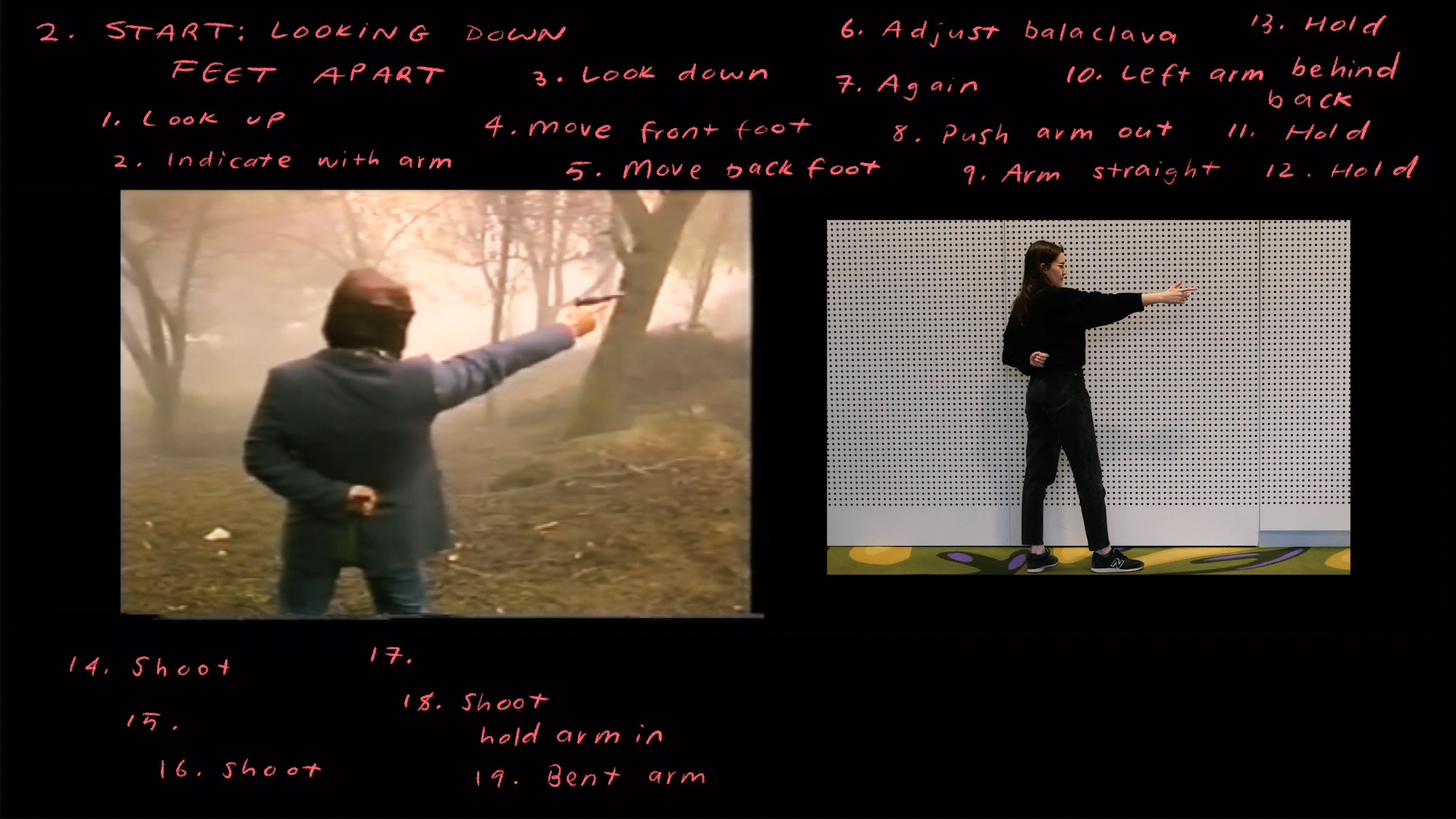

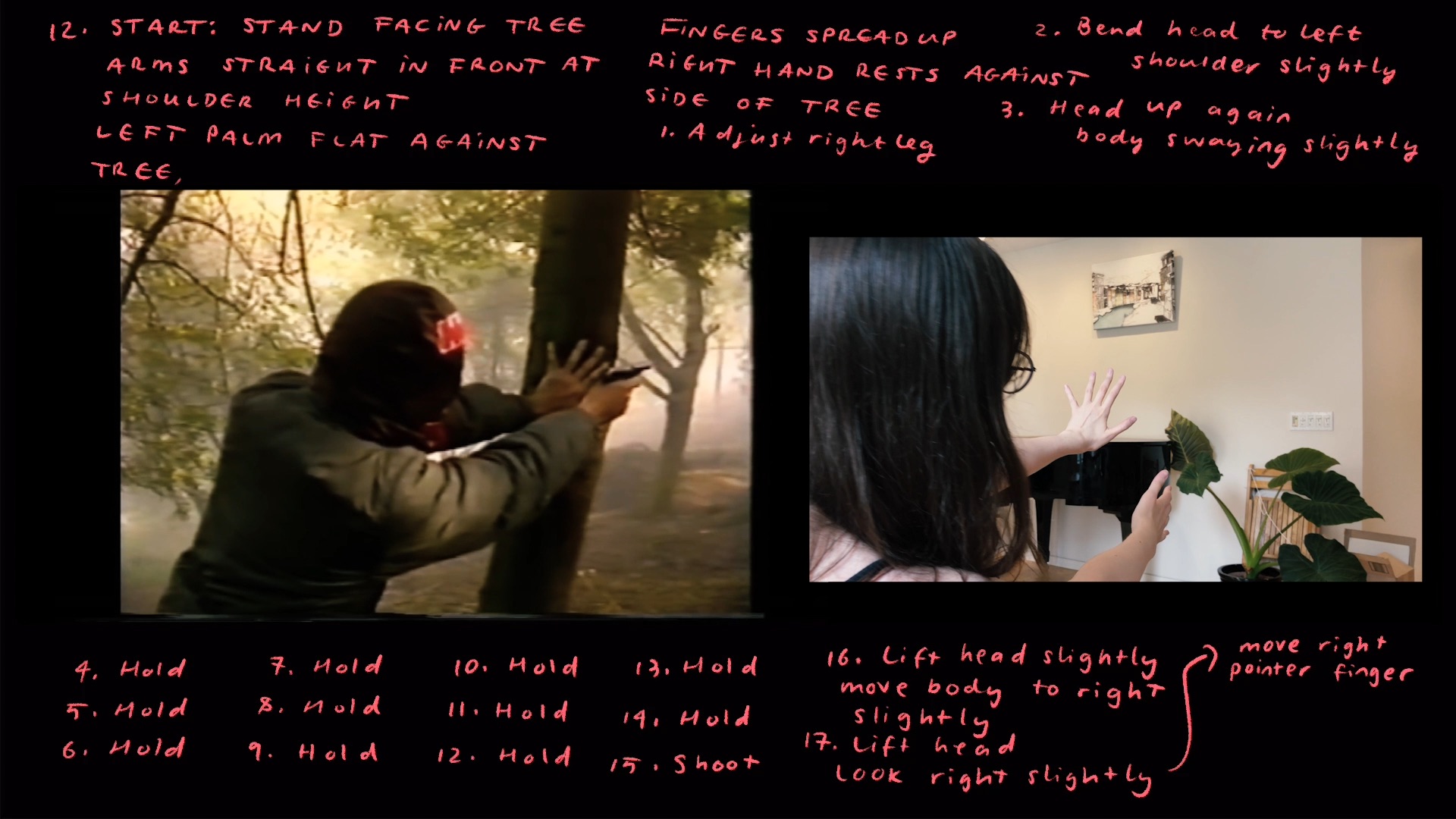

My stance on re-performance versus re-enactment was informed by my research for Vecino Vecino. I began developing Vecino Vecino by analysing keywords and building descriptions of scenes from the French segment. I translated the archival footage from French to English using Google Translate and then into Spanish by hand in real-time. This turned into translations of sequences from the original work onto my own body. To develop these movements, I worked with the dancer and choreographer Vanessa Vargas at the Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center at Rensselaer Polytechnic in Troy, New York. 6I had originally met Vanessa while taking her class “The Body in Exile” at the School of Making Thinking—an organisation dedicated to challenging disciplinary conventions in art making—in New York in 2018. This class informed the bulk of the choreography during Vecino’s early development. At EMPAC, we worked with movement scripts I had created based on scenes of MAPU members demonstrating how they trained to shoot guns in the forest of Cerro San Cristóbal in Santiago, Chile. I copied these movements and later worked with Vanessa to shape the individual gestures into a longer, abstracted sequence that features at the end of Vecino Vecino.

I finished Vecino Vecino towards the end of 2021, and it premiered at the 2022 Prismatic Ground Experimental Documentary Festival in New York City a few months later. It has since screened at the Festival Ojo al Cine, Colombia; RABIA Festival de Cine Latinoamericano, Argentina; Frontera Sur Festival Internacional de Cine de No Ficción, Chile; and MUTA Festival Internacional de Apropiación Audiovisual, Peru. As I write this paper in early 2023, I am preparing for Vecino Vecino to be presented in the exhibition Lejos, muy lejos at the Matucana 100 Cultural Center in Santiago, Chile, curated by Ignacio Szmulewicz. This pivotal exhibition is part of the programming marking fifty years since the Chilean coup d’état leading to the military dictatorship. By re-staging Vecino Vecino, adding additional digital prints and writing, and seeing the work in the context of programming devoted to unpacking the present through representations of the past, I returned to my notes for Time, After Time: a re-performance workshop.

II.

1: (Re)Sources

Author’s note: Re-performance is revisiting history to understand the past through the present. However, the use and intention behind re-performance in contemporary art vary between specific works. In this lecture, I looked at examples of artworks, types of source material, how and why they are used, and the shifting roles of the actors, artists, and audiences within these works. Within contemporary art, sometimes re-performance is an aim, a tool, and sometimes an element within a larger work. I proposed re-performance as a framework and a way of approaching the creation of art that looks to use or respond to histories, archives, and other source materials.

1.1 We access history through mediated means: archives, oral histories, technology, official history, books, photographs, and cultural memory. Re-performance offers us a way of looking at and dissecting the histories and stories each text recounts and the opportunity to interrogate the conditions of the source material itself: the mediums and contexts through which we view and access history.

I will be focusing on three types of source material. Firstly, familial. This includes stories, photographs, home movies, objects, and memories. Secondly, historical and archival, including official histories, oral histories, memories and accounts, documents, and events. And thirdly, cultural, specifically pop culture, which speaks to society and can highlight the ideas of public and private and includes music, film, books, celebrity, and performances and concerts. These come with their worlds of analysis and ways of reading.

Similarly, many artworks utilise re-performance, but grouping them conceptually under this umbrella is difficult. As Robert Blackson has articulated concerning reenactment, “this diversity of artistic intentions and approaches to reenactment is also what dissociates them from being considered a formal movement or genre in contemporary art”.7 Re-performance can be used alongside different methods and intentions and work with source material with its own frame of reference. As such, re-performance can include examining the conditions of the source material itself: how it came about, what gets remembered and how, what it’s used for, and how that affects or shows something about society. When considering the source material and work construction, artists must understand their intention and positionality to the source.

This analysis can help guide the construction of the artwork. For instance, in South Korean artist Jiwon Choi’s 2014 video work Generation’s Girl, Choi dances in front of a projection of YouTube footage of the K-pop group Girls Generation. The artist wears the same costume as the singers and re-performs the same choreography but can never fully integrate into the group. The video projection plays across her body, an obvious betrayal of her separation in space from the original performers. Here, an accurate re-performance is not necessary or even the goal. Choi’s decision to distance herself from the original performers enables readings addressing identity, fandom, media, and women’s equality.

1.2 Meanings and intentions come from the positioning of the roles of the artist, actor, and audience, and sometimes manipulation of those within the work. - Artist: Because source material can be very specific, it allows the opportunity to delve into the specifics of an artist’s interest. Why this source material? What is trying to be said about the larger world? What other layers can be added or connections, often across time (linking present and past), push the works further? - Actors: The actors are involved in the re-performance or set-up. This can be the artist, people who first experienced the event, actual actors performing a script, and even the audience. - Audience: The audience can be considered from multiple angles: witnesses, participants, and sources. An artwork using re-performance is not purely about the artist’s experience; it also includes the message being transmitted to the audience through re-performance. How does the re-performance put them in the scene? Are they active or passive viewers?

Use of the complication of these roles can be seen in Omer Fast’s 2003 film Spielberg’s List in which a replica of a concentration camp near Krakow was constructed next to its original as a set for Steven Spielberg’s 1993 film Schindler’s List. Fast constructed his two-channel video using footage from tours of both camps and interviews with extras from the movie, some of whom were also Holocaust survivors. Fast plays with the roles of the actors, the witnesses, the sources, the audience, and the artist by purposely muddling truth, half-truth, and fiction.

1.3 The creation of a script can be a useful starting point for an act of re-performance. The scriptwriting process can be a way of unpacking and engaging closely with a text or source material. Sometimes there is a clear script given to you already within the source. This could be recounting an event or instructions like a series of steps. But even when not, there are also less obvious things that can be scripted: for instance, sounds, gestures, rhythm, small movements, or light.

For Yoshua Okón’s 2011 video project Pulpo/Octopus, the event referenced doesn’t provide an exact “movement script,” but each participant’s memory does. Reflecting on the CIA involvement in the 1954 Guatemalan coup d’état, Okón used interviews and documented military manoeuvres to create choreography.8 The choreography was originally developed as storyboards tracking movement over time and providing the basis for a series of sequences performed and filmed in the parking lot of a Home Depot store. While using actors who originally were involved in the Civil War fighting in the 1990s, Okon has transposed the action to a contrasting location within the United States, creating a comment on the US involvement in the war and the US tradition of Civil War re-enactments.

You can create a script with the intention of an accurate performance, and you can write a script that purposely leaves room for interpretation. Scripts can be worked on and remixed to create an abstracted performance—more of a response to the source material. Many elements can be dissected and layered to build scores. You can incorporate sections from other source material as a collage to create further meaning for your work.

In a way, we can think of re-performance as a “song.” It is possible to dissect the elements of the source material to create a score that utilises references and interpolations of the original piece without being a direct copy. In the end, it ultimately creates something new which contains the complex meanings of the original material.

2: Ethics and the Archive

Author’s note: In this second session, I addressed issues of ethically using archival material, and the ethics of the archive itself. Re-performance allows us access to a range of thought processes around meaning, ethics, and personhood essential when creating works that use history and the archive. It is also a way to engage with under-represented histories and stories—bringing diverse archives into the present through art and analysing their access points and power dynamics. Re-performance is complicated by the intentions of the artist and the conditions of the past. This lecture discusses the ethics of creating re-performances, the role of power and empathy, and the use of archives. Continuing with ideas of scripting from lecture one, I looked at methods of abstraction as a way of addressing ethical considerations.

2.1 There is power in archives, and they often determine whose stories get remembered and how. When it comes to art making, I have a rather broad view of what an archive is: from official records to items found in personal collections. Heidi McKee and James Porter note that viewing archives as being solely official records omits most—in some cases, all—women, indigenous people, people of colour, people who identify as LGBTQ, people with disabilities, and people of lower economic status.9 By maintaining a broad view of the archival landscape, including valuing archival methods outside of institutions, we as artists create space for stories that have been historically overlooked or intentionally marginalised, in many cases, our own.

When working from source material, the conditions of that material are embedded within it. This can be questioned from multiple angles: from the objects themselves (how did they arrive in the archive? Was it collected with consent?) to the archivists (who decided to archive/store this? Who made choices about how it is arranged and kept?). Additionally, there are considerations of the moral rights for someone to re-perform materials, and for those wanting to present the source material, an issue of copyright.

There are many ethical and moral aspects to consider when developing work this way. As each work is subjective and dependent on context, it is important to be self-aware and flexible enough to adjust as you go along. In most cases, we, as artists, are not drawing the same conclusions as traditional researchers. There is no requirement to show the original documents or even a legible analysis of our references. As Michael Levan has noted when discussing the work of Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar, we can choose not to show the original material or to divorce the source from our work.10 However, it’s important to have an understanding (or be working towards an understanding) of why we are using the source material and the possible implications of that.

2.2 Following McKee and Porter’s research on archival ethics, when working with source material or archives specific to a person, it’s important to think of “recognizing the person-ness of archival materials”.[^11 ] Curator and theorist Inke Arns also recognises when we start looking at subjective histories and the context of a person’s life and the community and culture around them, objects, texts, and other source materials can be seen as an extension of the person.11 There is no clear distinction between the individual and the text when thinking this way. It is harder to define this distinction when considering the moral issue of consent instead of legal ramifications, but we can look to existing artworks for guidance.

Combining the personal, the political, and the journalistic is Argentine-American artist Silvia Kolbowski’s A Few Howls Again? (2010), which includes a reanimation of German political militant Ulrike Meinhof (1934-1976). She was a well-known journalist who joined the Red Army Faction (Baader-Meinhof group) active in West Germany in the late 1960s and 1970s when the radical left shifted into extreme factions. Members of the group, including Meinhof, were arrested, imprisoned, and died in jail. Although Meinhof’s death was pronounced as a suicide, her death was laden with controversy. In A Few Howls Again? Kolbowski takes a noted image of Meinhof after her death and reanimates it with a doppelganger. Beginning as a silent film with quotes by Meinhof and the media over a black and white photo, Kolbowski shifts the film into colour as the Meinhof stand-in turns to look at the viewer. The re-animation of Meinhof is used to consider the event itself, the actions of the state, and the purpose of the media’s framing while acknowledging the delicate personal-political nature of the source image—at once an image of a person while at the same time holding all semiotic meanings of its political context.

The double meaning of archive and context is a core element in July, 14th? (2013) by Kosovan artist Petrit Halilaj. In this video work, Halilaj approaches the Prishtina Museum of Natural History collection, which was entombed in the basement for 13 years following the ‘98/’99 Kosovo War. The video documents the opening and discovery of the condition of the collection, 90% of which was damaged and had lost scientific value. This film is part of a larger project that includes an installation of copies of taxidermal animals from the archive based on descriptions before they decayed.

While not specifically human-personhood, July, 14th? is an example of working with objects with stories to tell beyond their original intention: While the objects contained may have lost scientific value, they maintain historical and cultural value. The work examines the conditions under which an archive had been made, used, and stored while highlighting the historical and political circumstances that impacted these decisions. Halilaj deftly balances the many angles and contexts held within these objects through changing circumstances, re-production with intent, and acknowledgement of history.

2.3 There are ethical obligations to be considered when working with history, and in many cases, outside of strict legal considerations, there are no clear guidelines or rules to follow. Firstly, there is an obligation to the people involved who cannot consent because they’re deceased, and following them, their descendants. I believe there is also an obligation to third parties included in the source material/archive that don’t have a legal right to control how it’s used, as well as contemporary communities connected with historical material. Sometimes, these considerations fall outside of legal rules and more into the realm of personal philosophy and community responsibility. The question of what is public and what is private—especially after a long period—comes into play here. Is something that was a public document automatically available for use? What role does context play? What does this work/research contribute to the individuals, families, or communities it discusses? You may see consent as not given for another if consent was given for one context.

These questions come back to an understanding and analysis of our motivations to create the work and use specific source material. As mentioned, meaning is often found beyond our initial interest in the material. Instead, we need to connect with the broader issues we use to discuss and understand this source material. We must ask ourselves the key question: what are we trying to say with this work? By creating artwork in this manner, we are linking into histories and telling stories that may become part of the narrative and lineage. We must think beyond ourselves—both to the past and future that this work might influence or represent.

Carlos Motta addresses this in Six Acts: An Experiment in Narrative Justice (2010), developed during the 2010 election campaign in Colombia. Motta features actors re-performing testimonies of individuals who have suffered violence due to their sexual orientation or gender identity. The re-performance becomes a means of bringing marginalised voices into the public sphere, challenging the official narratives and fostering empathy and understanding. Motta describes these re-performances as a “fictionalisation of historical speeches through interpretation and performance,” transforming the work from a reflection to politics proper and having the ability to resonate and affect change in the present; “an eerie dislocation of time and place occurred… Gaitán’s words re-spoken today in front of the presidential palace were strikingly contemporary.”12 In this instance, the ethical considerations involve respecting the experiences of the individuals whose testimonies are re-performed and using art as a platform for social justice.

2.4 Sometimes, re-performance can be used to understand what another person was feeling or thinking through inhabiting their body movements or reciting their words. In some cases, this can be a problematic gesture that must consider the power balance within the relationship. Susan Leigh Foster notes that “the fact that colonizers could imagine themselves both inside the colonized body and also outside observing it established their omniscience and authorized their actions.”13 There is also a power imbalance between actor and observer or, as Foster puts it: “Those who feel and those who feel for them.”14 By embodying someone, presuming that we can take those motions away and into our bodies and understand what they are feeling, that power imbalance extends even further. This is not to say that this can never be used, but it goes back to fully understanding our intentions in creating the work and using the source material. Methods for working with these concepts vary. Asking for direct permission, consulting with stakeholders, or discussing with peers working similarly can all provide guidance and direction as one develops a work.

There is also the relatively safe(r) haven of responsive work rather than re-performative work. In these cases, I suggest using re-performance and scripting as a starting point to gain an analytical understanding of the archival text and then work beyond the text itself. Use it as a tool, a stepping stone, in which you break apart the script and focus on creating a response with those elements.

3: Memory and Mediation

Author’s note: In this final lecture, we looked at layers of truth and mediation within source material and how this can be extended through re-performance. I explored how re-performance can be used as a transitional tool to create works that speak to the mediated conditions of the past and the present and consider the role of cultural and personal memory.

3.1 It is difficult to decipher what is true in a world where technology and mass media filter the information we receive. Many works using re-performance pull apart the layers of mediation entangled within our episteme and perceptions of history. These works show how re-performance can problematise historical truth, reconsidering what was presented as truth, the forces that have shaped it, and the presentation of evidence. The way we access history is always mediated.[16] Whether through journalistic footage, documentary, film, video, audio, tropes or through the oral histories, archivists, concepts of the state, Institutions. We can also consider why certain images are available to the public: who decides what images are put forward and what they are trying to achieve?

British artist Rod Dickinson uses re-performance across his practice and as the basis for many projects. He usually works with actors and also includes a website component to his works that has extra information or plays into the idea of the project. In the live performance and installation Who, What, Where, When, Why and How (2009), Dickson uses the tropes of a generic political press briefing with few contextual clues, presented by a politician and an army officer who are seemingly interchangeable. They read excerpts from speeches that justify political actions, with each excerpt announcing that the time for speeches is over and the time for action is now. These media events have a worldwide impact, founded on a sense of legitimacy created through rhetoric and staging. In re-performance, Dickson is questioning the systems and ideologies at play in forming and presenting the evidence of events.

3.2 Collective memory can be mediated through a nation’s mass media and popular culture. A work that demonstrates how these three forces can be interconnected is Croatian director Renata Poljak’s video work Staging Actors / Staging Beliefs (Boshko Buha) (2011). Poljak’s work often examines the aftermath and impact of the breakup of Yugoslavia, particularly in connection with personal identity. In Staging Actors / Staging Beliefs (Boshko Buha), Poljak employs the actor Ivan Kojundzic, who, as a child, starred in the popular, eponymous Yugoslav film Boshko Buha. This pro-Yugoslavia film holds a sense of culture, identity, and collective memory of a certain generation. In Boshko Buha, Kojundzic portrayed a real person who was a Yugoslav Partisan resistance movement member. Interestingly, Kojundzic himself was later involved in fighting the Croatian War of Independence in the 1990s, which marked the end of the Yugoslav Federation—the cause the character he had played was fighting for. After the war, Kojundzic became a news anchor. Poljak’s work includes an interview, archival footage from his time as a newscaster, and scenes from the TV show Boshko Buha. “Once an actor who constructed ideology, he was now simply reporting the truth.”15 Staging Actors / Staging Beliefs (Boshko Buha) places different mediums in the same conversation across time, complicating decisions on truth and authenticity. By displaying one man’s ideology through re-performance, Poljak emphasises the performative ideology within ideas of nationhood and perceptions by popular media of self-described and questions how much of our identity is connected to ideas of nationhood.

Conclusion

That journey into the desert that you’d spoken of, you will take it alone? Once you said to me that peace and happiness might be found there, you gave me hope and now, now we have to say goodbye.16

Works that use re-performance are not merely exercises in replication. They are journeys of displacement and recontextualisation, shedding light on the ever-evolving, cyclical nature of history. In utilising strategies of re-performance alongside self-awareness and adaptability, we, as artists, embark on a continuous dialogue with the past: asking questions, challenging perspectives, and creating new narratives. The process of re-performance invites us to reimagine history, reconsider our roles within it, and navigate the ever-changing landscape of memory and interpretation. As we have come to understand, history is not objective; it is an ever-evolving narrative shaped by archives, media representations, and cultural memory. Re-performance allows us to dissect the stories within history and the conditions embedded within its archiving and recording. Working in this way takes time. Time to unpack and repack and consider ethical considerations of dealing with the material at hand. From my experience with Vecino Vecino, the creation of highly personal work connected to family runs in parallel to the hard work of unpacking this emotionally and sometimes physically within one’s life. This has been a self-analytical and rewarding journey within my practice and life. As artists, we must question and reevaluate our place in history, privileges and positions, and rights to use certain texts. It asks us to engage fully with the world in which our art exists, to communicate with stakeholders, to research and consider, and to create community and engagement around our practices. As I look back on the creation of Vecino Vecino and the presentation of these workshops, I am reminded that history is not confined to the pages of a book; it is a living and evolving narrative that continues to unfold with every reinterpretation, every recontextualisation, and every re-performance.

-

This quote is pulled from The Garden of Allah (1936) quoted in Cyndi Lauper’s Time After Time music video (1984). The title for this paper and for the workshop, Time, After Time, is taken from Cyndi Lauper’s song by the same title from 1983. Since running workshops by the same name (as discussed in this article) Lauper’s song has regularly appeared in my life: in supermarkets, karaoke bars, the name of a store in the Tropicana Casino in Atlantic City. In the music video Lauper is curled up in bed inside an airstream trailer sitting in the middle of the woods. Lauper mimes the words to an old film, “re-performing” the lines from The Garden of Allah (1936)—the third film based on a 1904 novel by British writer Robert S. Hichens by the same name. Through archives and cultural media, the iterative nature of history is made visible. ↩

-

The Lautaro Youth Movement or MAPU-Lautaro was a left-wing militant organisation who were active in the 1980s. See Erica Pearson “Lautaro Youth Movement” in The SAGE Encyclopedia of Terrorism, Second Edition (London: Sage Publications, 2011), 343. ↩

-

Vecino translates to neighbour Spanish ↩

-

Free Association is a platform for workshops, public programming, and publishing through the expanded fields of fiction, poetry, critical theory, philosophy, art and art criticism. ↩

-

For further reading on the debates between re-enactment and re-performance see Amelia Jones, ““The Artist is Present”: Artistic Re-enactments and the Impossibility of Presence,” TDR: The Drama Review 55, no. 1 (Spring 2011): 16–45 and André Lepecki, “The Body as Archive: Will to Re-Enact and the Afterlives of Dances,” Dance Research Journal, 42 no. 2 (Winter 2010): 28–48. ↩

-

This mentorship was graciously supported by the Australia Council for the Arts, now Creative Australia. ↩

-

Robert Blackson, “Once More … with Feeling: Reenactment in Contemporary Art and Culture,” Art Journal 66 no. 1 (2007): 37. ↩

-

Raúl Hernández Valdés, “Las extensiones del sentido/The extensions of meaning,” in Pulpo/Octopus, edited by Okon Studio (Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana: Mexico City, 2012) 5. ↩

-

Heidi A. McKee and James E. Porter, “The Ethics of Archival Research,” College Composition and Communication 64 no. 1 (September 2012): 60. ↩

-

Michael Levan, “Folding Trauma: On Alfredo Jaar’s installations and Interventions,” Performance Research 16 no. 1 (2011): 86. ↩

-

Inke Arns, “History Will Repeat Itself,” 8. ↩

-

Carlos Motta and Gabriela Rangel, “Enacting a Manifesto,” In The Creative Act, edited by Tone Hansen, (Torpedo Press: Oslo, 2012). ↩

-

Susan Leigh Foster, “Choreographing Empathy,” Topoi 24 (January 2005): 87. ↩

-

Foster, “Choreographing Empathy,” 82. ↩

-

Elaine Ritchel, “Evolving Beliefs: Renata Poljak Discusses New and Old Work,” Ikon Arts Foundation. Published March 3, 2013, http://ikonartsfoundation.org/evolving-beliefs-renata-poljak-discusses-new-and-old-work/ ↩

-

From The Garden of Allah (1936) quoted in Cyndi Lauper’s Time After Time music video ↩

Camila Galaz (1989, Adelaide, Australia) is a multimedia artist, writer, and researcher based in New York City. Her work looks at social histories of technology, identity through media archives, and reconsiderations of cultural touchstones. She is the creator and co-host of the podcast Our Friend the Computer with the Media Archaeology Lab, University of Colorado; member of the Superkilogirls research group with the Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam; contributing editor of the Millennium Film Journal; and a Y10 NEW INC Incubator Member at the New Museum, New York.

Acknowledgements

This research was originally developed as a curriculum for a lecture and workshop series for the Channels Video Art Festival and Free Association. It took place over two months at School House Studios in Naarm, Melbourne, Australia in 2019. The participants of this workshop were: Emanuel Rodriguez-Chaves, Elijah Money, Kate Stodart, Sumarlinah Raden Winoto, Kori Miles, Kate O’Boyle, Sha Sarwari, and Georgia Kartas. More information about the projects they developed can be found on the Free Association website.

I acknowledge the custodians of the land on which these workshops took place, the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation, and pay respect to their Elders, past, present and emerging.

Bibliography

- Arns, Inke. “History Will Repeat Itself.” In History Will Repeat Itself. Strategies of re-enactment in contemporary (media) art and performance, edited by Inke Arns and Gaby Horn, 1-9. Berlin: Revolver, 2007

- Blackson, Robert. “Once More … with Feeling: Reenactment in Contemporary Art and Culture.” Art Journal 66 no. 1 (2007): 28—40, DOI: 10.1080/00043249.2007.10791237.

- Blouin, Jr., Francis X. “Archivists, Mediation, and Constructs of Social Memory.” Archival Issues 24 no. 2 (1999): 101—111

- Foster, Hal. “An Archival Impulse.” October 110 (Autumn 2004): 3-22.

- Foster, Susan Leigh. “Choreographing Empathy.” Topoi 24 (January 2005): 81-91, DOI: 10.1007/s11245-004-4163-9.

- Gere, Charlie. “The technologies and politics of delusion: an interview with artist Rod Dickinson.” Stud. Hist. Phil. Biol. & Biomed. Sci. 35 (2004): 333—349, DOI: 10.1016/j.shpsc.2004.03.010.

- Kolbowski, Silvia, and Michèle Thériault. “Models of Intervention.” In Nothing and Everything, edited by Michèle Thériault, 1-8. Montreal: Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery, 2009.

- Levan, Michael. “Folding Trauma: On Alfredo Jaar’s Installations and Interventions.” Performance Research 16 no. 1 (2011): 80—90, DOI: 10.1080/13528165.2011.561678.

- McKee, Heidi A., and James E. Porter. “The Ethics of Archival Research.” College Composition and Communication 64 no. 1 (Sep 2012): 59-81

- Motta, Carlos, and Gabriela Rangel. “Enacting a Manifesto.” In The Creative Act, edited by Tone Hansen. Henie Onstad Art Centre and Torpedo Press, 2012.

- Ritchel, Elaine. “Evolving Beliefs: Renata Poljak Discusses New and Old Work,” Ikon Arts Foundation. Published March 3, 2013, http://ikonartsfoundation.org/evolving- beliefs-renata-poljak-discusses-new-and-old-work/

- Valdés, Raúl Hernández. “Las extensiones del sentido/The extensions of meaning.” In Pulpo/Octopus, edited by Okon Studio, 5-11. Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Art Matters, 2012. http://yoshuaokon.com/assets/pulpo_hernandez2.pdf