Re-staging Chaos Ander and the Underground Chilean Cultural Scene

The first time I visited Chile, over a decade ago, I walked through the streets of Matucana and San Martín, passing the building street numbers 19 and 841. These numbers and names meant nothing to me at the time. They appeared as banal urban spaces: a hardware store (19) and a housing department (841). However, I now know more about what happened inside those buildings in the 80s and felt affected by memories I technically did not experience. I was not there, but I have tried to recreate some of the histories of these spaces. I engage the memories of artists who were there and artworks and archives that survived oblivion and obscurity.

I can explain my fascination with Chilean art of the 1980s: when I lived in Santiago, I had direct contact with many of the artists, art historians and art critics who worked in that decade; I became immediately attracted to the fusion between disciplines that took place at that time, and the persistence of, in a small dose, the eighties energy in the unruly Chile of the new millennium. Also, why not say it: my anemoia for the Movida Madrileña, which took place in Spain, and my inclination for the marginal, the peripheral, and the political. All of this led to my curatorial research leaning toward the 80s.

For most of the 2010s, I lived and worked in Santiago, learning, analysing, interviewing and researching artists from the 1980s and sometimes the 1970s, a generation of creators who had invented new aesthetic strategies during the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990). At the same time, hegemonic art centres of art became interested in artists working under the dictatorship. In turn, retrospective exhibitions, acquisitions for museum collections, essays, awards, and rediscoveries ensued.1 However, most of these outputs focussed on the escena de avanzada, a group of conceptual artists and writers living in Santiago canonised in Chilean art history today.2

Other Chilean creators from the 1970s and 1980s still needed to make it into books, exhibitions and museums. These are “the dissidence of dissent,” in the words of Ramón Griffero, one of the protagonists of the Chilean underground. A heterogeneous group that, for the most part, was not so interested in conceptual art and did not receive the attention of institutional spaces or art critics.

In this essay, I trace my interest in the Chilean underground, focusing on the two cultural epicentres active from the early 1980s in Santiago: El Trolley and Matucana 19. More than this, I seek to analyse how, from the second decade of the twenty-first-century perspective, it’s possible to engage with histories of the 1980s curatorial work critically. I focus on my curatorial project entitled Ander (2022), which was shown at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Chile. In this essay, I chart my curatorial methodologies for engaging and re-staging the activities and the “vibe” of El Trolley and Matucana 19, prioritising intergenerational dialogue, archival knowledge, and sensory, affective encounters with the past to impact the present.

The Underground

The Trolley and Matucana 19 were two sheds led by local creative youth in the 80s—many of them recently having returned from exile—which hosted concerts, exhibitions, plays, performances, meetings of magazines and comics, poetry readings, feminist events, parties and political actions during the Chilean dictatorship. Because of their fragile, fleeting and unclassifiable nature, many of these experiences had been lost or were unknown to the public and the history of local art.3

Pablo Lavin, a recently returned exile, opened El Trolley in 1983. Its location: 841 Calle San Martin, Santiago, surrounded by brothels, a prison and the headquarters of the investigative police (torture centre). Lavin returned in 1983, intending to create a cultural space in a slum, drawing on his experiences of the culture that ensued in squats on the outskirts of London. He adapted the warehouse of the Empresa de Transportes Colectivos del Estado de Chile (State Collective Transport Company, ETC), which at the time was in disuse. He opened it up to theatre, music, performance and parties. The shed became the headquarters of the Fin de Siglo Theatre Company, led by the Griffero, whose experimental and committed theatrical works became profoundly influential in Chile. Further, El Trolley hosted hundreds of events: performances by Vicente Ruiz, concerts by Los Prisioneros, Javiera Parra, Tumulto, UPA, or the Banda del Pequeño Vicio, and events such as the First Underground Biennial, launches of magazines such as Noreste, Mapuche dance shows, exhibitions and temporary murals by Pablo Barrenechea, Bernardita Birkner, Bruna Truffa, and Roberto di Girolamo, video-art premieres by Gonzalo Justiniano, Carlos Altamirano and Enzo Blondel, or poetic readings by Santiago Elordi, Cristián Warnken, Sebastián Grey or Juan Pablo del Río.

In a story similar to that of El Trolley, exiles Rosa Lloret and Jordi Lloret opened Matucana 19 after returning from exile in 1983. Rosa Lloret had fled to Paris in 1974. Her brother, Jordi Lloret, migrated to Barcelona. They did not think twice when their father offered them the chance to occupy the garage he had abandoned at Matucana 19. The siblings returned wanting to create a collective, collaborative cultural scene, bearing in mind such references as the Movida Madrileña. They gradually converted the old garage their father had used as a car wash company into an open space: they painted the space, brought in seven ping-pong tables, a radio cassette player to blare music, and took out a patent for recreational games and artistic exhibitions. They transformed the space in the mid-80s into a site for rehearsals and concerts of punk and new wave bands, film screenings, art exhibitions, dances, performances, murals, launches of magazines and comics, and creative events linked to the political and social context. Jordi Lloret recalls that first moment in a series of interviews conducted during the research period of the exhibition: “It was a blank page that began to fill with curious young people. We all took the party as a form of resistance.” Fatigue, the absence of economic benefits to face debt (they had failed to pay real estate taxes), led to the sale of the garage space in 1991 (El Trolley ended in 1988). During its heyday, an endless number of activities took place at Matucana 19, such as the “Cena Papal” (“Papal Dinner”), decorated with the flag of Vatican City, the broadcast of the fall of the Berlin Wall, the “Fiesta del Colón Irritable” (“Feast of the Irritable Columbus”) of October 12, the “Fiesta ON” (“Feast ON”), held after the victory of the “no” vote that ushered in democracy into Chile, and finally, the visit of actor Christopher Reeve -known for his role as Superman, who spoke out to the defend the group of actors and artists of Matucana 19 threatened by the dictatorship. This event registered the arrival of thousands of people, including sex workers from the neighbourhood, who, according to Jordi Lloret, welcomed the actor with yelps of “Let him fly, Let him fly!”

Although the Llorets and Lavin returned from exile with many international references, what emerged inside these two sheds had no precedent. With creative freedom as a priority, they faced excessive censorship, which made self-censorship disappear. In the Trolley, a new theatrical language began with El Teatro de Fin de Siglo (1983-1988) by Ramón Griffero with scenographies by Herbert Jonckers, or, in Matucana 19, with El Teatro del Silencio (1989-1999) by Mauricio Celedón. Here, artists translated punk, pop, and rock rhythms into a local language with bands such as Fiskales Ad-Hok, Pinochet Boys, Electrodomésticos, and Viena. The performance reached new heights with Vicente Ruiz and the Las Yeguas del Apocalipsis. Magazines and comics experienced a golden age, as seen in publications like Matucana, Trauko, Noreste, Daga or Beso Negro. The visual arts explored new fields thanks to Victor Hugo Codocedo, Contingencia Sicodélica or Colectiva Wurlitzer. Space and time for people hitherto discriminated against in the artistic field arose as seen in the Mapuche performances of Lorenzo Aillapán or gender debates in the multitudinous event of Las 3,000 Mujeres. All of these actions occurred with complete autonomy from the mainstream and state media: the “do it yourself” ethos prevailed and became a method and motto for young people dressed in North American clothes that cited cultural movements from the 60s and 70s, especially punk, remodelled to generate a unique style: the Chilean new wave.

Lavin, Griffero, Jordi Lloret and Rosa Lloret incited the activities of Trolley and Matucana 19, turning disused sheds into cultural centres where the avant-garde, the party and the resistance went hand in hand. The regime’s authorisation for the exiles to return in 1983 contributed to the return of young talents who brought European influences. However, due to the economic recession of 1982/83 and the dictatorship, they found themselves in a country limited by a curfew and without cultural budgets. Still, their oppositional stance outweighed their financing difficulties; they were able to experiment, criticise and denounce the dictatorship through creativity and generate works and actions that, most times, were shown on a single occasion.

Curating the Underground

In August 2020, the producer Matías Cardone and the exhibition designer and artist José Délano contacted me to propose the curatorship of an exhibition on Chilean art of the 80s. They reached out because of my previous work with the art of that period and because I am a foreigner in Chile.4 It was assumed that my foreign gaze would offer some distance from local politics for this adventure. In a country with a reduced art ecosystem, partly because of the neoliberalisation of everything in Chile, it is easy to fall into professional and personal philias and phobias, manifesting in nepotism or, on the contrary, marginalisation due to enmity. I could escape from that mill wheel cycle. Rather than developing an exhibition on the Chilean underground based on a theme or a common thread among a list of names, I proposed that we focus on animating the cultural life of just two spaces, El Trolley and Matucana 19, since they were the most active, the most visited and the most influential.

To reference the Spanish pronunciation of “under”, we named the exhibition Ander, representing a critical, “Chilean-style” translation of the European underground movement. Ander was a word used by some of the protagonists of both spaces, places that harboured humour but also resistance: a will to live.

We offered the project to the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, which was accepted, and we applied for a Chilean state cultural grant, which they awarded us. We had an exhibition space, funding, and date secured. However, the most challenging issue needed resolving. How can we exhibit at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in 2022 what took place in the eighties in two disappeared sheds?

Little by little, the curatorial team agreed based on the work and our intention:

- • Recreating emotions. Rather than exhaustively showing the history of these spaces academically, we would focus on evoking energy, an environment, with an approach that privileges the affective and sensory. In any case, it would not make sense to produce a chaotic period in which the creators worked without thinking about the archive or posterity and without the intention of being considered by the institution but seized by the dissident through an academic project. We wanted to offer the viewer the possibility to listen to music (through audio bells, open audio, and headphones), to sit down to see a play or performance, to play and to leaf through period magazines (we printed exact copies of the originals for the exhibition). Moreover, we presented archives and support structures to hold the artworks or audio-visual material that hints at the materiality or vibes of the concerts, exhibitions, and events that initially took place in both spaces. For example, we constructed a ping pong table to display such art under glass to show small-format drawings rather than pinning them on a white cube wall. The ping pong tables were an iconic element in Matucana 19, which began its journey by inviting its neighbourhood residents to play.

- The past within the present. We sought coherency between the materials we used and the events, actions and works of art we reproduced without denying current techniques (provided that these were at the service of reproduction and did not stand out above the content). The most challenging re-enactment for Ander was “Eclipse II”, an installation shown at Matucana 19 in 1987 by the artist Víctor Hugo Codocedo. Many elements composed it: three wooden trunks and public lighting poles leaning against the wall; a flag of Chile on which the film Nosferatu (1922) was projected; a wall clock; a chair pierced by a spear, and the shadow of the chair painted black; an exhaust fan whose blades caused an intermittent shadow; a series of photographs of the artist’s previous works; a sign that read “Pharaoh has a face again”; and, last but not least, a horse. As an anecdote tells us, initially, the horse was meant to be on-site at Matucana 19 for two weeks. However, Codocedo took pity on the horse and released it a week later “because he [the horse] began to get nervous, which proves that we are all fatigued by the confinement”, as he had commented to a local newspaper during the show. For Ander, we recreated Codocedo’s installation following the order in which the artist had arranged the elements in Matucana 19: a clock identical to the original, a flag on which Nosferatu was reproduced, and rather than include an actual horse, we simulated the living horse as a digital projection. In addition, we showed photographs that Jorge Brantmayer took of the original installation, sketches by Codocedo, and the original poster. We even displayed a handwritten notebook by Codocedo days after dismantling the installation, in which he implied the frustration he felt for the little understanding and the little diffusion that his work had had in Matucana 19.

- Maintain error and criticism. We included a book that witnessed one of the events included in the exhibition and that, in its description, made mistakes. Leonardo Aller’s Dadá: Underground en dictadura: La Calabaza del Diablo (2011) states that Tiananmen (1989) was the first-ever performance by the now iconic art collective Yeguas del Apocalipsis. This is not true, but we included the book in the show because those legends were part of the spirit of the spaces. We concluded that our mission was not to correct errors but to be faithful to the sources of the time and to refer to what happened as accurately as possible. We also included a statement by Francisco Casas of Yeguas del Apocalipsis, who considered the scene of Matucana 19 as elitist and bourgeois. We had that criticism as wall signage. Sometimes distance makes up and exalts the past, and, again, we would do a disservice to the search for objectivity.

- Contact zone. Establish links between the tumultuous and creative past and the present through parallel activities (interviews and conversation tables, workshops, film cycle, musical performance at the inauguration, website activation and creation of own content on social networks). For example, during the development of the exhibition, a historic vote took place in Chile, the choice between the “approval” and the “rejection” of the proposal for a new national constitution5. In our social networks, we discussed the vote (obviously, without expressing an inclination for one or another option) by way of history, remembering the plebiscite that occurred in 1988 and opened the doors to the end of the dictatorship and the beginning of democracy.

- Second readings. The approach to the exhibition was emotional and sensory (the information in the room was basic, and simple and accessible language was used). However, the exhibition offered, to those viewers who wanted it, a deep and detailed contextualisation. A free fanzine was published that analysed the show’s works and a catalogue dedicated to exploring both spaces through exhaustive research, fed by personal interviews with the protagonists of the time, the few existing written references, and the conclusions obtained after studying the derivative works of art. At the same time, and showing another example of current technology in a historical review exhibition, we used QR codes that offered information about each work, expanding and adding another format to those physically present in the room.

- Consistency between the content and how it is displayed. We followed this ethos by trying to get the same materials or aesthetics initially used in the 80s. For example, in the fanzine for Ander, we used typographies, textures, aesthetics and layout methods used at the time. If we approached a period highlighted by the influence of “do it yourself” and punk music, we reflected these methods and aesthetics in our recreation.

- Understand and access spaces and works through the protagonists’ voices. We conceived our revisionist project by engaging the testimony of those who lived through an era. We recorded interviews in 2022 with the promoters of the two cultural spaces and reproduced them on two screens in the exhibition. For some of the wall text, we included some of the most memorable phrases the protagonists spoke during our interviews with them in 2021 and 2022 (and had the interview date). We also included verbatim quotations taken from magazines of the 1980s that gave an account of some of the activities in the Trolley and Matucana 19. During the show, we hosted interviews with the original protagonists in a different non-museum location (called the “control tower”) and organised round tables, open to the public and accessible. We dedicated posts reproducing interviews on social networks or including paraphrases and quotes to their discussions. In addition, our team had the advice of two of the protagonists of the spaces, who offered us, better than anyone, a personal and empirical perspective towards the cultural events of the exhibition.

Going down to the underground

In the MNBA, the spectator who wanted to visit the exhibition had to follow an arrow pointing them downward to the museum’s basement gallery (Matta Gallery). The basement seemed an excellent venue for encountering the Chilean “underground”. This architectural location allowed a perfect allegory of the indifference that officialism and the history of art applied to the activities accumulated in Trolley and Matucana 19.

An enormous mirror is in the stairwell leading to the museum’s basement gallery. On its surface, we wrote “Where is the underground?” drawn from a news report from the time. We wanted the question to prompt viewers to locate the answer in the show. As a secondary function, we knew that the mirror would encourage “selfies,” something we planned by adding URLs/links to the museum’s social networks on the mirror.

In front of the gallery entrance door, the viewer saw a vast black wall on which we projected a selection of videos, fragmented and edited, drawn from the show. We wanted to offer a sensory and vague encounter of what was inside the room, not regulated, homogeneous and parcelled but instead chaotic, confusing, and promiscuous. This projection included a brief introductory text to the exhibition:

The Trolley and Matucana 19 were counterculture centres in Chile in the 80s. In these two sheds, plays, performances, concerts, exhibitions, debates, exhibitions, launches of magazines and comics, and events of a feminist nature took place. They happened under dictatorship.

The party and the resistance went hand in hand on the part of young people who generated works and actions that, in many cases, were shown on a single occasion. Moreover, they did it with autonomy: the “do it yourself” ethos prevailed.

No one even considered making money from their creativity, and different “urban tribes” and people from diverse social and economic realities lived together. They needed to get together, create, shout and laugh. There was a rebellion against the absence of freedoms, hedonism, and debauchery.

Thirty years have passed, perhaps the distance needed to address the cultural resistance of the eighties. Welcome to ANDER.

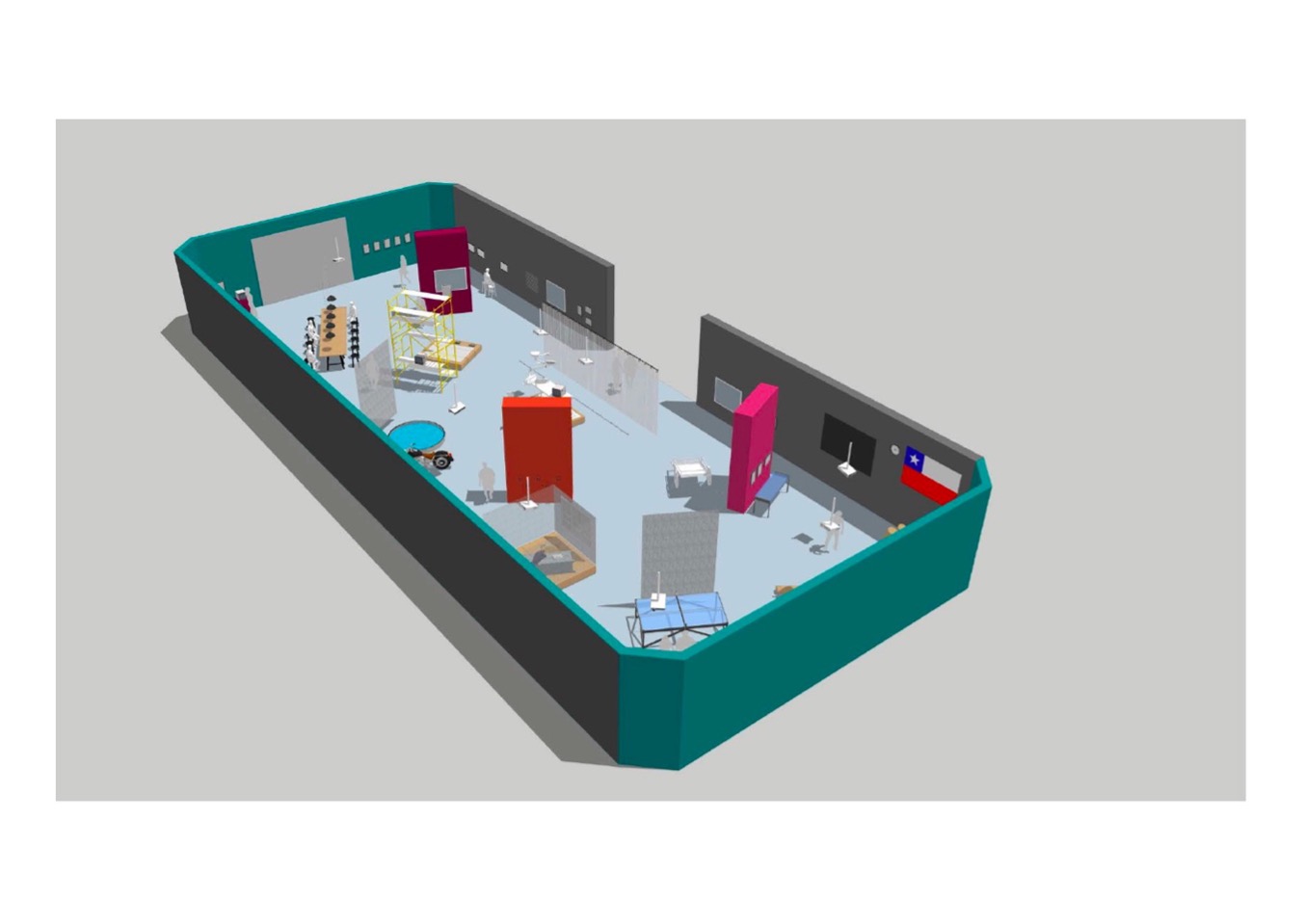

Within the Matta Gallery, we exhibited the works without an order through which visitors should pass through the show, without a division by themes or disciplines, and without a central axis from which, radially, a narrative expanded. We treated the space as if it were a large shed. The exhibition’s lighting was low intensity to be consistent with a party vibe and the spirit of the works.

Paintings, drawings, screens, photographs, writing, magazines, installation, vitrines, projections, and sound occupied the entire gallery space in an alleged disorder, with some elements of identification or with the mission of amalgamation: for example, we used the colour pink in parts of the exhibition. In the central area of the gallery, we presented the milestones, those works to which we devoted greater attention.

Some small-format informal works or archives helped us communicate to young viewers the historical depth of what they were seeing. At the entrance of one of Griffero’s plays, the organisers of Trolley presented a typed invitation warning the public that they would postpone the function in case of curfew. The invitation is torn in a corner, yellowed by the passage of time. However, this small document can forcefully communicate the moment’s tension, uncertainty, and risk. The other object we presented for historical context is the bass-machine gun of the punk-rock band Índice de Desempleo (Unemployment Index). This group always understood music as a field of political turmoil from its very name, which alluded to the dubious official figures of the volume of active workers. For the exhibition, we commissioned an exact copy of the original bass that the band’s bassist, “Tatán” Millas, had built in the 80s, and which is inspired by the AKA-47 rifle that appeared on the flag of the Manuel Rodríguez Patriotic Front. It sounded perfect, and you can see him in action in the music video for his song “Warema K.K.” (1988). We included the recreation of that bass-machine gun because we thought this object, better than any other, combined the political character with the playful.

During and after the exhibition, the team received numerous compliments from the public and specialised media. The one that most stimulated us was that of the protagonists of the time. I am not naïve: I know that if someone expresses criticism in person, usually, it will be positive. In my opinion, the number of spectators or the satisfaction of the artists involved is not the measure of the success of cultural outputs. For me, what determines whether the impact of artistic and cultural work is greater or lesser lies in its ability to inspire another person to do something of their own, another work driven by what they saw, heard, or read: Something that is impossible to compute.

However, if both the public and specialised media repeated something, it was the relevance of Ander’s exhibition design by Délano, which maintained an antagonistic position to violletleduquism.

The rule of Viollet-le-Duc

I had researched previous exhibitions that revisited, recreated or reconstructed samples from the past. I did it with one of the samples analysed in two volumes I published in 2018 and 2020 (Curatorship of Latin America I and II, Cendeac editorial), in which I investigated Latin American historical exhibitions and interviewed their curators. It was Tropicália. A revolution in Brazilian culture (1967-1972), curated by Carlos Basualdo and toured by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, The Bronx Museum of the Arts in New York, the Barbican Art Gallery in London, and the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin.6 Basualdo, aware that the tropicalist movement, in its artistic section led by Helio Oiticica and Lygia Clark, was unrepeatable, decided to reconstruct some of the works and installations that took place in the years of the “Brazilian cultural revolution”7, generating through them a new experience. To do this, he commissioned various contemporary artists to create new works capable of dialoguing with the sixties works of that subversive and dictatorship-dependent Brazil.

Another example I had in mind when developing Ander’s exhibition design with Délano was the most famous exhibition in the history of contemporary curatorship: When Attitudes Become Form (1969), curated by Harald Szeemann. When the Diego Portales University of Chile invited me to elaborate on the subject of “The History of Curatorship”, I analysed the exhibition and its two subsequent recreations; one of them, in my opinion, was very successful, and the other, which I had the opportunity to see in person, a disaster. When Attitudes Became Form Become Attitudes (2012), curated by Jens Hoffmann for the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco, was based on Szeemann’s 1969 exhibition but focused on new commissions from creators such as Zarouhie Abdalian, Abraham Cruzvillegas, Annika Eriksson, Simon Fujiwara, Jeppe Hein, Jonathan Monk, Nicolás Paris or Hank Willis Thomas. They responded directly to the history of the 1969 show. Contemporary artworks were displayed alongside archival materials, plans and images from the 1969 exhibition, making no distinction between what was past and what was present. In 2013, at the Prada Foundation in Venice, curator Germano Celant, in dialogue with Thomas Demand and Rem Koolhaas, developed the exhibition Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form, trying to be as faithful as possible to the ‘69 show, something impossible, especially considering that what Szeemann was attempting to expose were “attitudes” and not “forms”. Celant’s revision was replete with errors, free adaptations, and reconstructions that he did not identify as such and, in its entirety, read as a lifeless, academic rereading of something elusive, malleable, and imprecise.

However, the most direct antecedent, or anti-antecedent, to Ander was Losing the Human Form, an exhibition that I visited in its itinerancy to the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid (2012-2013), an analysis of which I also included in my book Curatorship of Latin America.8 The collective Red Conceptualismos del Sur, who curated the show, sought to review the art of resistance in 1980s Latin America in what I’d describe as an academic exercise; it was an exhibition showcasing an enormous amount of archives with minimal recreation. A crystal palace composed of dozens of vitrines that captured written documents and photographs as if they were collections of stuffed insects. A show that was going to be read by audiences rather than seen or touched. A doctoral thesis in three dimensions, something that conflicted with the content of the exhibition: rebellious art, subversion, hooliganism and agitation.

I told Délano my intention to do something as distant as possible from “Losing the Human Form” and he understood it instantly. Délano brilliantly proposed a reactivation from the sensory, visual, Ander, and we c and aesthetic, away from a surgical and aseptic look. Moreover, we didn’t want to fall into the errors of the “restorers” of previous artistic experiences, that our “signature” be compared to that of the original creators.

In his restorations of the city of Carcassonne, which suffered a period of neglect, the nineteenth-century French architect Eugene Viollet-le-Duc was able to eliminate existing elements and add new creations alien to the original style and material. For the restoration of Carcassonne, he used materials not typical of the area for the reconstruction, such as slate (instead of native tile). He altered the towers’ structure, finishing them with a dome instead of the traditional terrace of the region. Self-centeredness and the need to stand out over the restored object, Viollet-le-Duc immortalised himself by including a statue of himself in Notre Dame Cathedral. Those who confused that effigy with that of St. Thomas left doubts when they saw what the figure carries in his hand: a ruler with the signature of Viollet-le-Duc.

Délano proposed a museography at the service of the works of art without fuss, distortions or stridency. The key to the excellent symbiosis between the work of art and the display resided in the fact that Délano was present in all phases of the conceptualisation of this exhibition, even in the initial state, when they were still nothing but attempts and thoughts. Thankfully, the dialogue between museography and curatorship was fluid, horizontal and constant.

However, this essay chronicle is not a hagiography. I have to accommodate criticism here. An artist, part of the underground, disagreed with our selection of works. In another case, an artist requested that we remove a painting depicting her naked body from the exhibition. During the long process before the inauguration, there were comments about the fact that the vast majority of the team were young professionals who had not experienced first-hand what we were showing. One of the museum workers, who had already positioned herself against this project because she considered it alien to the institution’s programming, said that several artists had yet to feel accepted by the project. Another person criticised the curator for being of Spanish origin, describing my presence as colonialist and extractive. During the Ander seminar at the museum, one of the attendees denounced that we, the curatorial team, had appropriated the anti-dictatorship discourse. Although no one stopped us, it is divisive to recreate, 40 years later, works that never had the will to be anything more than fleeting and to give transcendence to those who never possessed such an intention. I considered all these adverse reactions, even those I disagree with. Sometimes, you must listen, incorporate criticism, and rectify the situation or error when reasonable. At other times, you have to maintain boundaries.

Understanding today by revisiting yesterday

Ander archived its processes with the intention that its research work and collection of oral sources should not be an end to the underground’s history. The Ander website houses, and will continue to house, the content our research generated, just as the fanzine and catalogue will remain in libraries and households. We are also planning on publishing a book that will expand on our research and include archives and histories that did not make it into the exhibition.

For me, Ander was an exercise in activated memory about what happened in two spaces that had been almost forgotten. Its most outstanding quality was not looking back per se but tracing a possible connection between current struggles, especially after the Estadillo Social9, and their origins. In Trolley and Matucana, one of the first feminist events in Chilean culture occurred. Here, art defended the rights of the LGBT, now what we term queer, collectives. A cultural space in Chile hosted a Mapuche performance for the first time. And some works proposed a reflection on care for the environment.

Perhaps for this reason, Ander was an exhibition attended by a young audience: Twenty-somethings who, in 2022, were discovering for the first time what twenty-somethings did in 1982. Who could understand passions, actions and DIY works made with little money but which were far-reaching? What is most valuable for me is that they reflected on how young people escaped and faced censorship under dictatorship,10 while today, they are self-censoring under democracy. This anemoia, this nostalgia for the unlived, this seduction of the way of dressing, putting on make-up, posing, singing or expressing oneself was part of exercising freedom.

Let me return to one of the pieces in the exhibition. Perhaps one of the most fragile, of the least striking. In the handwritten notebook by Victor Hugo Codocedo, he wrote that he was frustrated by the little impact his work had, days after dismantling Eclipse II. What would Codocedo feel, who died in 1988 at age 34, that in the 2020s, his installation would be revisited? It is vital to continue investigating and recreating the works of the past; many of them have the power to continue giving meaning to the present. We revitalise the legacy of these eclipsed artists because their resistance can still energise ours.

-

Some examples are the exhibition “Losing the Human Form” at the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid (2012-2013), Cecilia Vicuña’s 2022 Venice Biennale’s Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement, or the research of Francisco Copello’s work carried out by the AMA Foundation since 2018. ↩

-

Escena de Avanzada was a concept developed by French-Chilean cultural critic Nelly Richard in 1981 based on the production of artists and writers who made conceptual artworks committed to the political context after the 1973 coup d’état, such as CADA, Carlos Altamirano, Juan Castillo, Eugenio Dittborn, Diamela Eltit, Carlos Leppe, Lotty Rosenfeld and Raúl Zurita. Nelly Richard, Una Mirada Sobre El Arte en Chile, 1981, Santiago de Chile, available: https://icaa.mfah.org/s/es/item/730121#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=-934%2C-83%2C3057%2C1711 ↩

-

. To cite some of the books and essays that helped to build the history of Trolley and Matucana 19: Aguayo, E. (2012). Las Voces de los ’80: Conversaciones con los protagonistas del fenómeno pop-rock. RIL editores; Lukinovic, J. (2015). La canción punk de los 80 en Chile. Oxímoron; Guerrero del Río, E. (1996). La creatividad a Escena (teatro chileno de los ochenta). Variaciones Sobre El Teatro Latinoamericano: Tendencias y Perspectivas, 85–102. https://doi.org/10.31819/9783964567789-005; Munsell, E. (2011). Subculturas Visuales y la Intervención Urbana. Santiago de Chile 1983-1987. Comunicación y Medios, 0(20). https://doi.org/10.5354/0716-3991.2009.15012; S., R. G. (2006). Poéticas de Espacio Escénico: Herbert Jonckers: Chile 1981-1996. Ediciones Frontera Sur; Conejeros, M., & Trigueros, I. (2008). Los Pinochet boys: Chile (1984-1987). Midia Comunicación; Paredes Figueroa, J. (2021). Jorge Canales. 2019. punk Chileno 1986-1996. 10 años de autogestión. Contrapulso - Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios En Música Popular, 3(1), 95–99. https://doi.org/10.53689/cp.v3i1.86; Jeria, A. L. (2011). Dadá: Underground en dictadura. La Calabaza del Diablo. ↩

-

I have written monographs about artists of the ’80s, such as Gonzalo Díaz (Art Nexus 103, Dec-Feb 2017); Yeguas del Apocalipsis (Art Nexus 95, Dec-Feb 2015); Carlos Leppe (Art Nexus 110, Sep-Nov 2018); or Paz Errazuriz, (Art Nexus 97, Jun-Aug 2015), an interview with Nelly Richard for the Spanish newspaper El País (May 8 2017), or with Elias Adasme for the magazine El Mostrador (September 10 2013), and articles about the period, such as “Residuos Americanos (La Revuelta del Arte Chileno de los 80)”, (A*Desk, April 2017), or “Avant-Garde in Chile in the 80’s” (Art Press 53, March 2020). ↩

-

On September 4, 2022, Chileans were called to vote on the proposal for a new Constitution emanating from the Constitutional Convention. The “Rejection” option won with 61.86% of the votes. ↩

-

Santos Mateo, Juan José (2020) “Curaduría de Latinoamerica Vol II”. Ed. Cendeac, Murcia, España. Pag. 179-197. ↩

-

Movement started in Brazil in the 1950s, which brought together creators from all cultural disciplines. See more at https://revistapesquisa.fapesp.br/en/cultural-revolution-brazilian-style/ ↩

-

Santos Mateo, Juan José (2018) “Curaduría de Latinoamerica Vol I”. Ed. Cendeac, Murcia, España. Pag. 339-363. ↩

-

Estallido Social was a series of massive demonstrations and riots originated in Santiago de Chile and spreading to all regions of the country, developed between October 2019 and March 2020. The demonstrators were protesting the systematic and continuous abuse of corrupt businessmen and politicians. ↩

-

On the censorship imposed from the institutional framework during the dictatorship, it is valuable to read Donoso. F. Karen. (2019). Cultura y dictadura: Censuras, Proyectos E Institucionalidad Cultural en Chile, 1973-1989. Ediciones Universidad Alberto Hurtado. ↩

Juan José Santos is an art writer, curator and researcher. He holds an International PhD in Artistic, Cultural and Literary Studies from Autónoma University (Spain). He is a member of the Researcher Group DeVisiones, Discursos, Genealogías y Prácticas en la Creación Visual Contemporánea. His work appears in Artforum, e-flux Criticism, Art Review, Spike Art Magazine or ARTNews, as well as in journals such as El País. He was a contributor of Arte! Brasileiros with a section of exhibition histories. He has been contributor-editor of Momus, editor-in-chief of Arte al Límite, and director and founder of Art on Trial. He is the author of two compilations of essays and interviews focusing on historical exhibitions; Curaduría de Latinoamérica (Vol I, Ed. Cendeac, 2018, and Vol II, Ed. Cendeac, 2020), and the art criticism book Juicio al Postjuicio.¿Para qué Sirve la Crítica de Arte Hoy? (Ed. Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes de España, 2019). Amongst his recently curated exhibitions are Extraña Dignidad (Museum of Contemporary Art, Chile, 2023-2024), and Ander (National Museum of Fine Arts, Chile, 2021-2022).