Maps and Circulations A Way of Expanding Biennials through Time and Space?

In 2019 and 2020, Brazil and Italy commemorated their biennials with exhibitions of exhibitions. The exhibition I Bienal Latino-Americana de São Paulo: 40 anos depois [First Latin American Biennial of São Paulo: 40 years later] sought to retrieve and question this milestone of the São Paulo Biennial, which endeavoured to mark a shift from the hitherto international orientation of the event.1 By contrast, Le muse inquiete—La Biennale di Venezia di fronte alla storia [The Disquieted Muses—When La Biennale di Venezia meets history] was intended to be a moment of reflection on the Biennale’s century-long history, exploring how it has been intertwined with social and cultural transformations, and historical and geopolitical events.2

Based on materials held in the Arquivo Multimeios of the Centro Cultural São Paulo (CCSP) and the Archivio Storico delle Arti Contemporanee (ASAC), photographs, videos, newspaper clippings, and documents entered into dialogue in the respective exhibition spaces. The symphony between these materials created the opportunity to reconstruct these fragments of biennials from a plurality of perspectives, which reflects the complexity of what an exhibition is. A portion of the exhibited materials have been documented in the catalogues, which, complemented by artistic and historical texts alongside photographs of the rooms, evolved into visual and documentary sources. In this way, these restaged biennials recalled an event and generated material for future readings.

Reesa Greenberg argues that the increasing number of exhibitions that remember themselves points to a developing interest in the history of exhibitions. “Remembering exhibitions” can be defined as discursive events, dynamic cultural moments of exchange or occasions to spatialise memory (making it tangible, current and interactive). They can alter past and future perceptions of what might be defined as the exhibition condition. Furthermore, the rise of this format demonstrates how the need to remember exhibitions has become part of contemporary exhibition culture.3

Restaging can be conceived as an “afterlife” of an exhibition. The restaged exhibition represents, remakes, and reinterprets the documents, testimonies, and traces left by other exhibitions. Likewise, the revisions and reinterpretations to which the exhibitions are subjected lead to the generation of new memories in addition to the previous ones.4 Moreover, the act of restaging enables the complexification of the exhibition as a medium. The materials it has produced are “objects of time” because different times coexist within them: the time of those who produced them, that of those who engaged them, that of those who preserved them, and that of those who take them back and use them again.5 Their juxtaposition and questioning in the exhibition space, or academic research, offers lessons about these dilated and fragmented, sometimes even contradictory times, and brings them into dialogue.

The materials produced by the exhibitions also show the different agents (including curators, artists, critics, art historians, museum directors, collectors, etc.) involved in them. Moreover, they reveal how exhibitions were places of meeting and exchange, where transnational networks converged, giving rise to alliances and the inception of collaborative projects.6 For example, the meeting between the art collector Peter Ludwig and the director of the Centro Wifredo Lam Llilian Llanes during the IV Havana Biennial (1991) gave impetus to the project of bringing the Biennial to Germany. In 1994, after the closure of the fifth edition, a section of Arte, Sociedad, Reflexión [Art, Society, Reflection] crossed the Atlantic and was exhibited at the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst (Aachen).7

Thus, precisely by starting with the understanding of an exhibition as a place of encounter and exchange, acknowledging that revisiting an exhibition creates fresh memories that often overlap with existing ones, one wonders what new perspectives the study of circulations of people and ideas and the use of maps in biennial research could contribute? How can analytic maps “expand” the event beyond the exhibition space, including other locations, temporalities, agents, and biennials?

What I am proposing entails a form of re-staging that moves away from the physical exhibition space and into written text, animating the history of exhibitions through text and images. In effect, an article like the one I am describing serves as a locus wherein the “objects of time” produced by exhibitions are questioned and interpreted, acquiring a new and more complex temporality. It is also a place where the exhibition can be expanded visually and contextually, tracing multidirectional plots that take us to other latitudes.

On this occasion, the focus will be on the Havana Biennial and its first three editions (1984–1989). Yet, despite its weight in the history of biennials, the Havana Biennial has not been the subject of a “remembering exhibition.”8 The reason for choosing these five years is its importance for the Biennial itself, as these years witnessed the development and consolidation of the Wifredo Lam Centre project, the institution organising the art event, as well as the establishment of the exhibition model that projected the Havana Biennial internationally.9

This article does not intend to restage a particular edition but to question some of the materials produced by this exhibition, such as the reviews and articles in newspapers and magazines and the documents of the theoretical meetings, to see what new perspectives they offer on this and other biennials. Furthermore, the article will attempt to show how the transformations of the Havana Biennial model are based on changes at the global level and on personal exchanges.

Why Maps and Circulations? A Brief Overview of Exhibition Studies

The study of the history of exhibitions is a relatively recent phenomenon. It was in the 1990s that the urgency of studying exhibitions, their histories, structures, and socio-political implications became apparent. An essential contribution is Thinking about Exhibitions (1996). This book brings together essays by curators, artists, sociologists, and historians on the history of exhibitions, forms of staging and spectacle, and questions of curatorship, spectatorship, and narrative. It also includes a bibliography on the subject of art exhibitions.10 This pioneering book has been a turning point in the study of exhibitions, which today are investigated by various methods, approaches, entry points and historiographies.

The current abundance of these publications goes hand in hand with their heterogeneity to the extent that some research has sought to identify and classify the different methodologies of this disciplinary field.11 In a very schematic way, and without claiming to be exhaustive, these include chronological or individual approaches, perspectives based on the display, or relating to curatorial practices. The exhibition space has played a leading role in these by various means.

Exhibitions have been studied chronologically, creating a linear history (even sequential) where these artistic events are concatenated one after the other. Publications such as Salon to Biennial and Biennials and Beyond analyse a set of exhibitions to reconstruct a synthetic history of each one by compiling textual and visual materials.12 In contrast to this approach with ‘universal’ pretensions, the Afterall series Exhibition Histories proposes an exhaustive analysis of an exhibition, presents a plurality of voices (artists, curators, and historians) who explore it from various angles, and provides visual sources for the reconstruction and understanding of the artistic event under examination.13

Other approaches analyse the exhibition as a visual tool that intensifies, critiques or reinforces a way of seeing based on the analysis of spaces and presentation methods. It analyses how exhibitions are organised, installed, and designed, from the design of the exhibition as an aesthetic medium and a historical category to the impact of exhibition devices on the interpretation of works of art.14 Thus, they study the relationship between the history of exhibitions and art history. Likewise, recent investigations have delved into the crossed narratives of exhibitions and curatorship. They show how their histories are interwoven since curating as a practice and exhibition as a medium function in a complementary way.15

The study of an exhibition is also somewhat complex because of the multiple layers (artistic, political, and historical) of which it is composed. In this regard, Bruce Ferguson defines exhibitions as situated intertexts: they must be seen based on their forms, contents, and expressive forces within the environment and historical conditions in which they are proposed and received, as the poetics and politics of exhibitions are interrelated and interdependent.16 Furthermore, as Olga Fernández López points out, they are a place of meeting and debate, where the artistic field’s personal, political, and economic relations are projected.17

The understanding of an exhibition as a place of encounter, debate, and exchange entails paying particular attention to the circulation of ideas and people. Indeed, the study of transnational exchanges, cultural encounters, and processes of cultural transfers enables the construction of a more plural and polycentric historical and artistic narrative.18

In Circulation in the Global Art History, Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, Catherine Dossin, and Thomas Da Costa Kaufmann point out that by studying the transnational circulations of images, styles, people, and ideas, it is possible to escape the cultural hypostasis of the bipolar and unidirectional narrative. The authors also remark that, despite its importance, the study of the circulation of people and ideas is still a marginal trend (especially in comparison to the analysis of circulations of images and style).19 This field is as yet little explored in exhibition studies. Nevertheless, I consider it important as an investigation of this kind allows us to understand how these circulations (and the resulting exchanges) have affected the perception of the art historians, critics, artists, or curators involved in the biennials.

In this regard, one must consider cultural transfers, namely the transformations that ideas, texts, or objects undergo when they cross borders and are analysed in new contexts. Simultaneously, it is necessary to consider the transformations that these contexts undergo when receiving and welcoming objects and ideas.20 Moreover, the specificity of each context requires a comparison of the political, social, and cultural realities of the areas under analysis.21

I envisage a biennial as an exchange zone where heterogeneous networks intersect, merge, or confront and create maps of relationships. By giving visibility to these networks, the processes of transfer and exchange and their relationships with different geopolitical and art-historical contexts enable us, on the one hand, to articulate dense multidirectional plots in the history of biennials. On the other hand, one may trace a transnational history of complex geographies, relationships and overlapping cartographies.22

In such an investigation, employing maps as instrumental tools can offer new perspectives.23 It should be noted that the use of maps in art-historical research remains a marginal trend; however, as Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel points out, the potential inherent in this methodology for art-historical research is considerable. Maps help one see and think differently and observe relationships or aspects that reading texts, statistical data, or images do not illustrate.24 Consequently, they become a tool for explaining, teaching, and visualising the object of study in novel ways.

In biennial studies, maps have predominantly been used to quantify the phenomenon or to illustrate its global extent. Such maps are useful given the transnationality of the biennial phenomenon and the circulation of people, works, and ideas therein.25 I think that maps can enhance comprehension of how an exhibition was conceived and developed, what agents or forces were at work in it, and its territoriality or subsequent critical reception. Therefore, maps may be perceived as a means to enhance the scope of the exhibition because they help us reconstruct and understand it, not only limiting it to the exhibition space but also other places, temporalities, and agents.

As a working tool, maps must be used with cognisance of their potential and limitations and should be one of many ways to approach the object of study. Working with maps requires a scrupulous methodology and a careful analysis of the results.26 The collection and processing of data needs to be thorough and reasoned so as not to give rise to partial, biased, or “directed” readings. It is also important to scrutinise the maps with the awareness that they may conceal others while they render certain results visible. In the case of network analysis, for example, they can provide evidence of cultural exchanges that challenge canonical narratives. Still, they can also minimise the complexity of temporality, relegate hierarchies to the background, or silence mechanisms of marginalisation.27 This helps us to understand how, in analysing the results given by the maps, the underlying artistic, political, social, and economic issues must be further considered.28

Questioning maps

Reviews and articles in newspapers and magazines are often the main sources for studying an exhibition. The information they impart varies in that it changes according to the period and how the exhibition is understood. In broad terms, they provide information about the event, the participating artists and the works exhibited.29 These articles also offer insights into the locations and occasions in which a particular exhibition was discussed, as well as the personalities who were interested in it, and their analysis can help one ‘access’ the exhibition from a different perspective. Likewise, the data collected from this approach can be cross-referenced with other data, which, in turn, offers new perspectives on the artistic event.

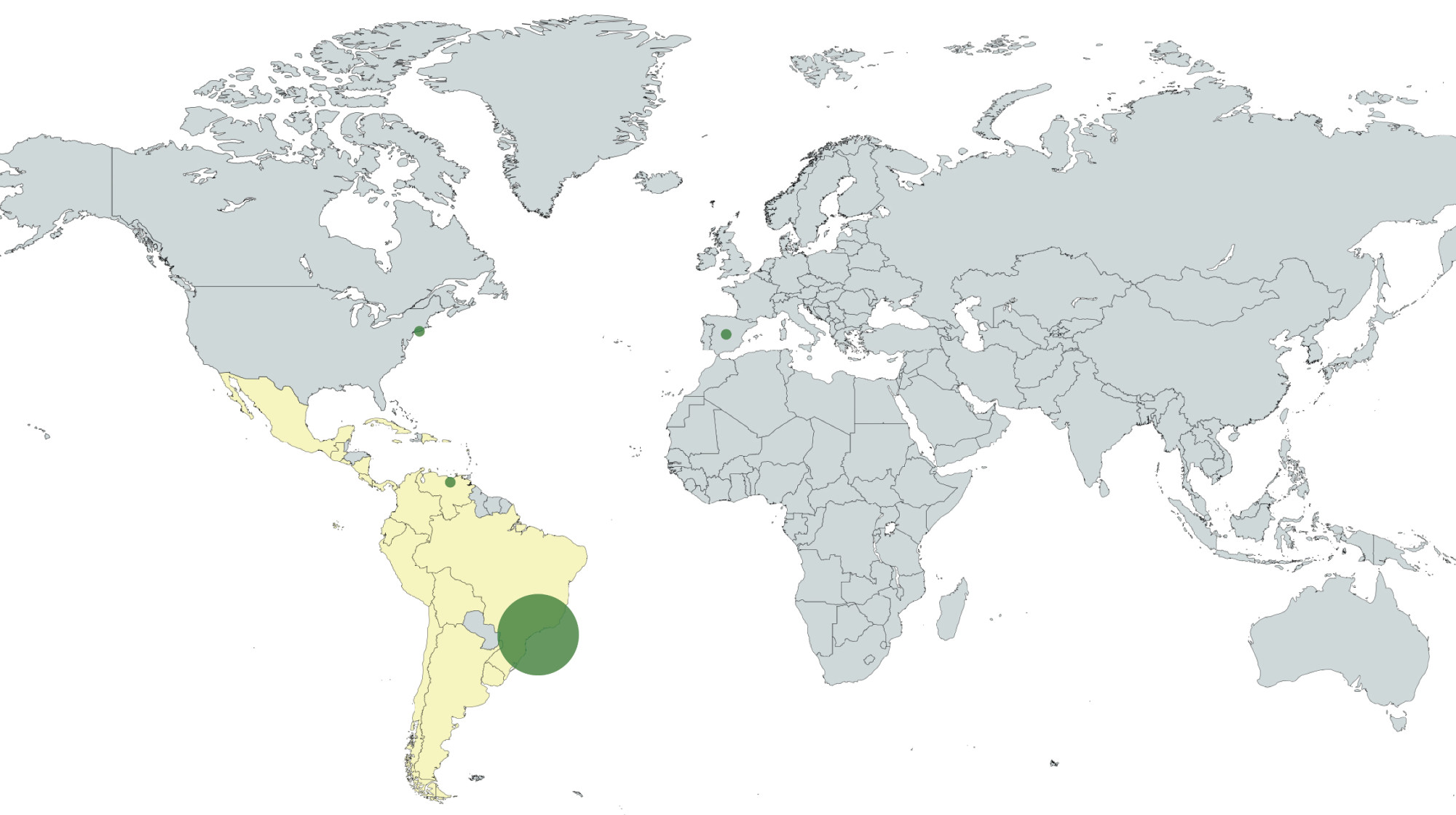

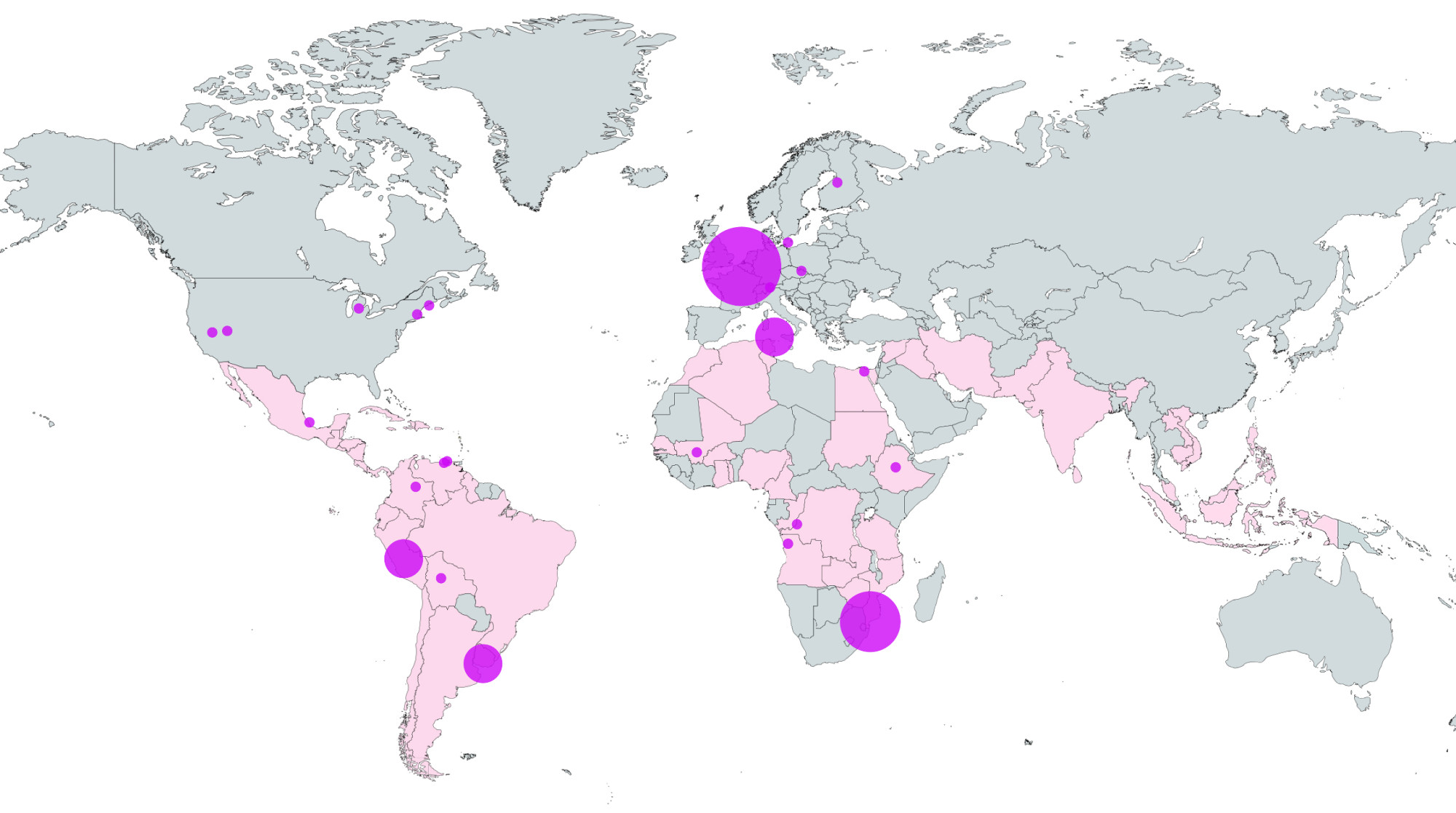

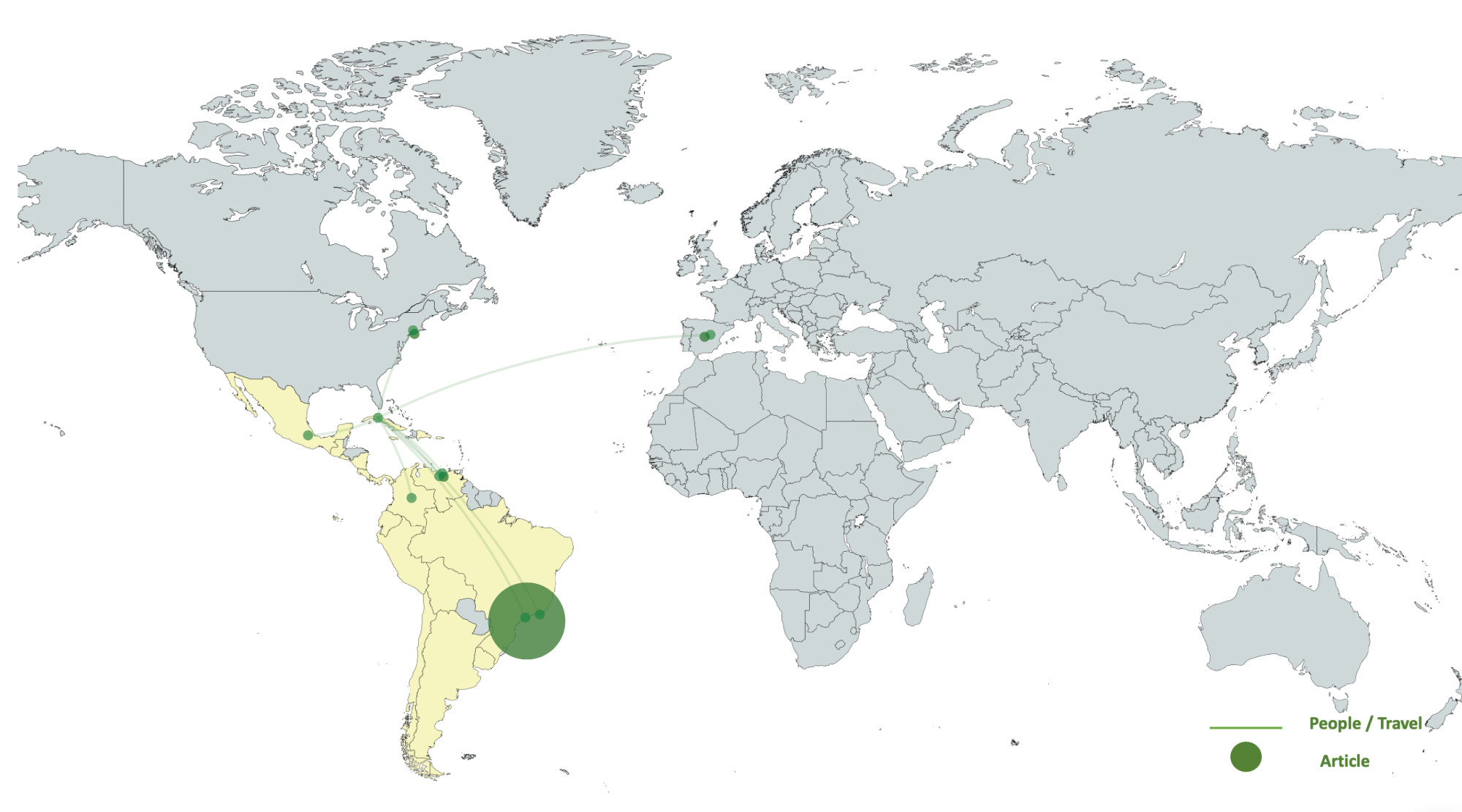

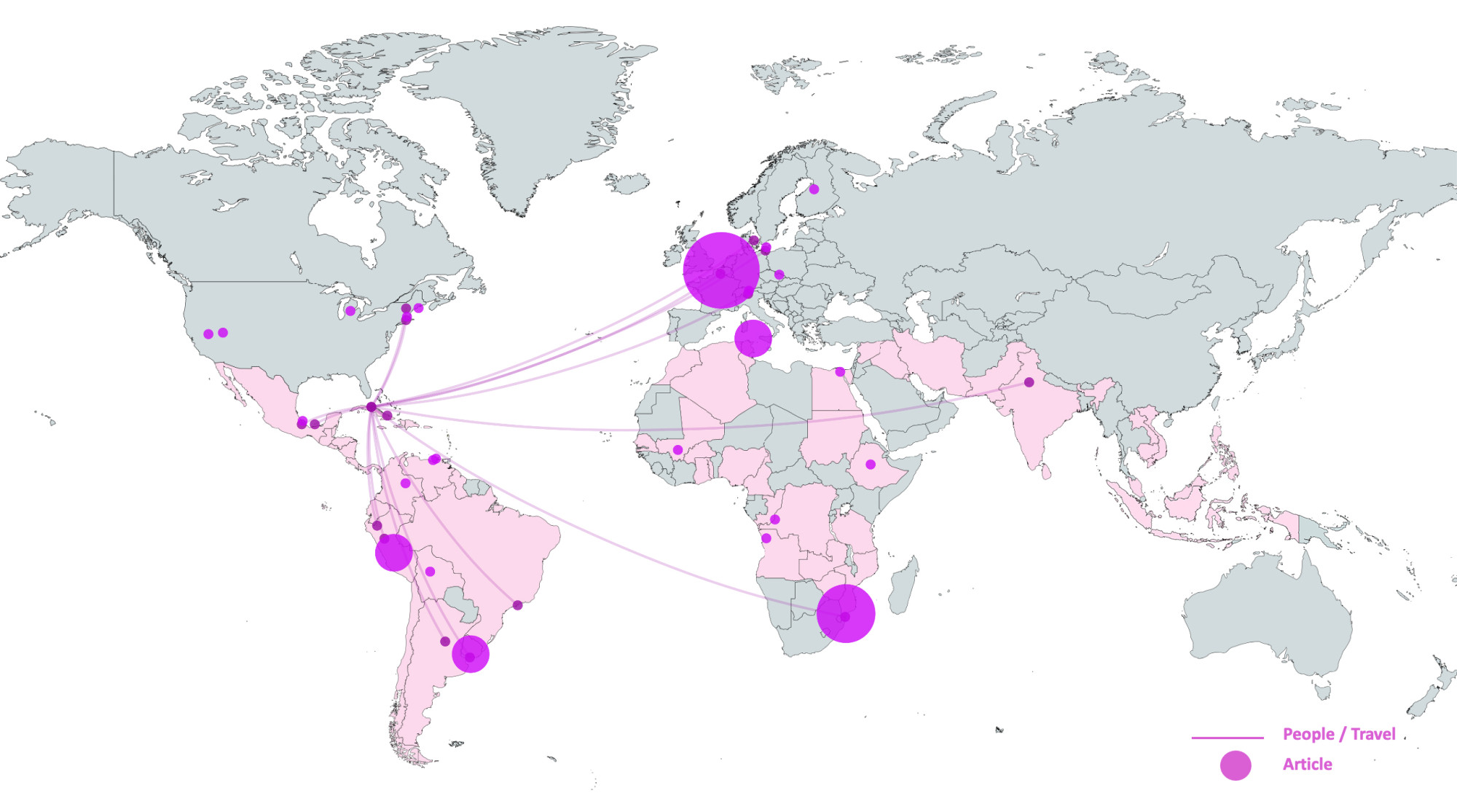

For example, the geospatial analysis of the press and public of the first two editions of the Havana Biennial helps us to question them from the point of view of the dissemination and reception of this Biennial and its project abroad.30 If one analyses, from a quantitative point of view, the articles or reviews on the first and second editions of the Havana Biennial, one can observe a considerable increase (Fig. 1 and 2). Furthermore, if one crosses these quantitative data with those of the foreign public who visited the Biennial, it emerges that, unlike the second edition, in the first, the articles are written only by people who visited the Biennial (Fig. 3 and 4).31

Examining the map relating to the press coverage of the First Havana Biennial, one notices that the place where the most articles were written (a total of three) was Brazil; in the map that also shows the foreign public, there is a connection between São Paulo and Havana. If the documentation found at the Wifredo Lam Centre provided me with the quantitative data, it was only when I consulted the funds of the Wanda Svevo Historical Archive that I understood the nature of this network and its repercussions.

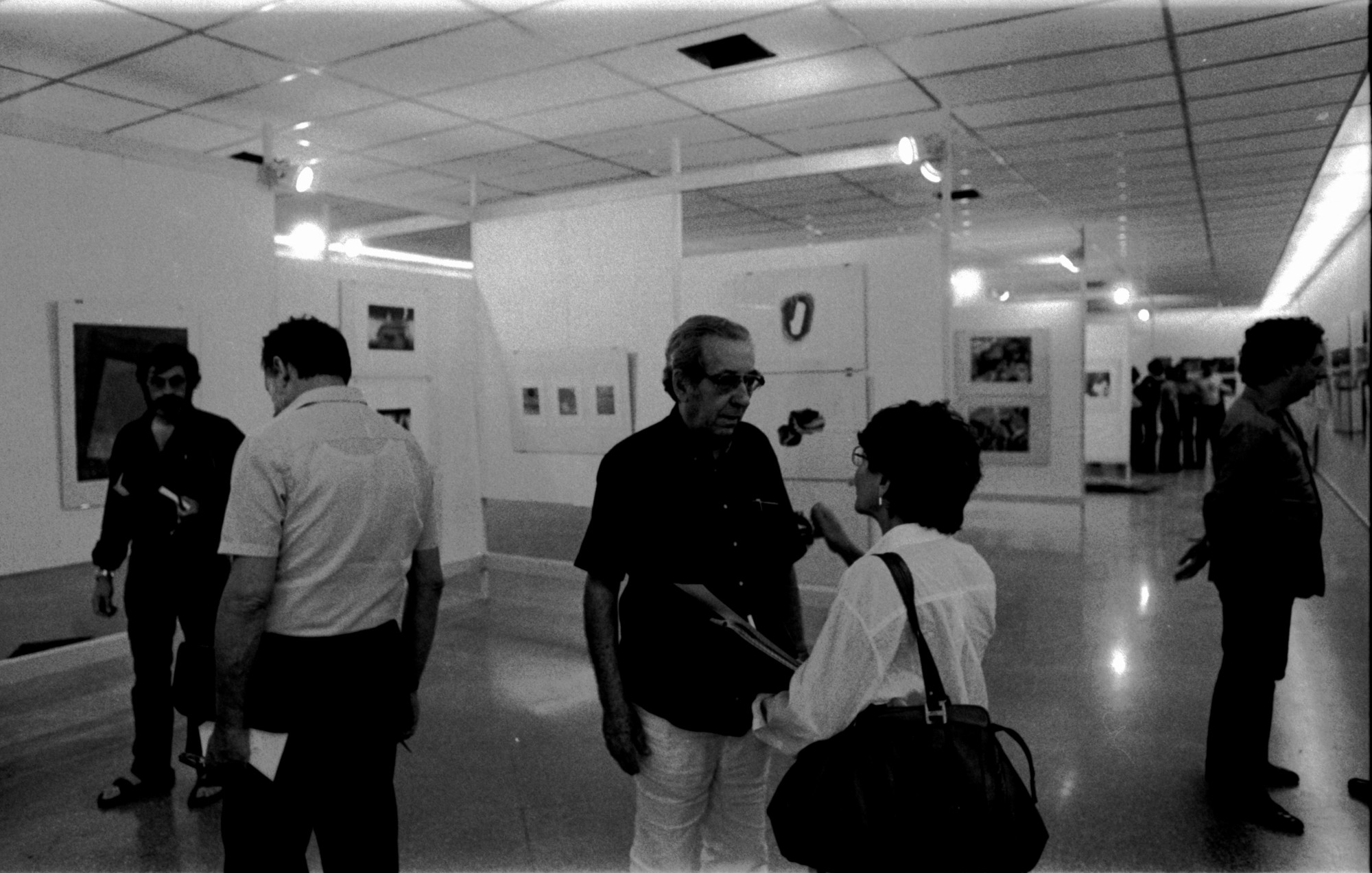

A large Brazilian delegation visited the Biennial, which included Aracy Amaral, Luis Villares, Roberto Muylaert and Sheila Leirner, among others.32 The origin of the trip can be traced, in the case of Amaral, to her participation as a member of the jury (Fig. 5), and in the case of the others, to the invitation formalised by the Cuban Ministry of Culture to Villares (President of the São Paulo Biennial Foundation, henceforth FBSP, during the 16^th^ and 17^th^ Biennial) and later extended to Muylaert (President of the FBSP during the 18^th^ Biennial) and Leirner, curator of the 18th São Paulo Biennial.33

Interestingly, this biennial delegation was the only one to attend the event despite the non-existence of diplomatic relations between the two countries. The contacts established there were essential for the return of artworks by Brazilian artists and, additionally, for the return of Cuba to the São Paulo Biennial after twelve years of absence since its last participation was in 1973.

Indeed, due to the isolation of Cuba, both the dissemination of the call for entries to the Biennial and the sending of artworks took on an unofficial character. In the first case, it was distributed by people who travelled abroad with the help of cultural institutions or associations of solidarity with Cuba. In Brazil, the José Martin Cultural Association oversaw relations with the Biennial. Regarding the shipment, many artworks had travelled long and complicated routes before arriving in Havana, going from Latin America to Europe (mainly Madrid and Paris) and then back across the Atlantic to Havana.34

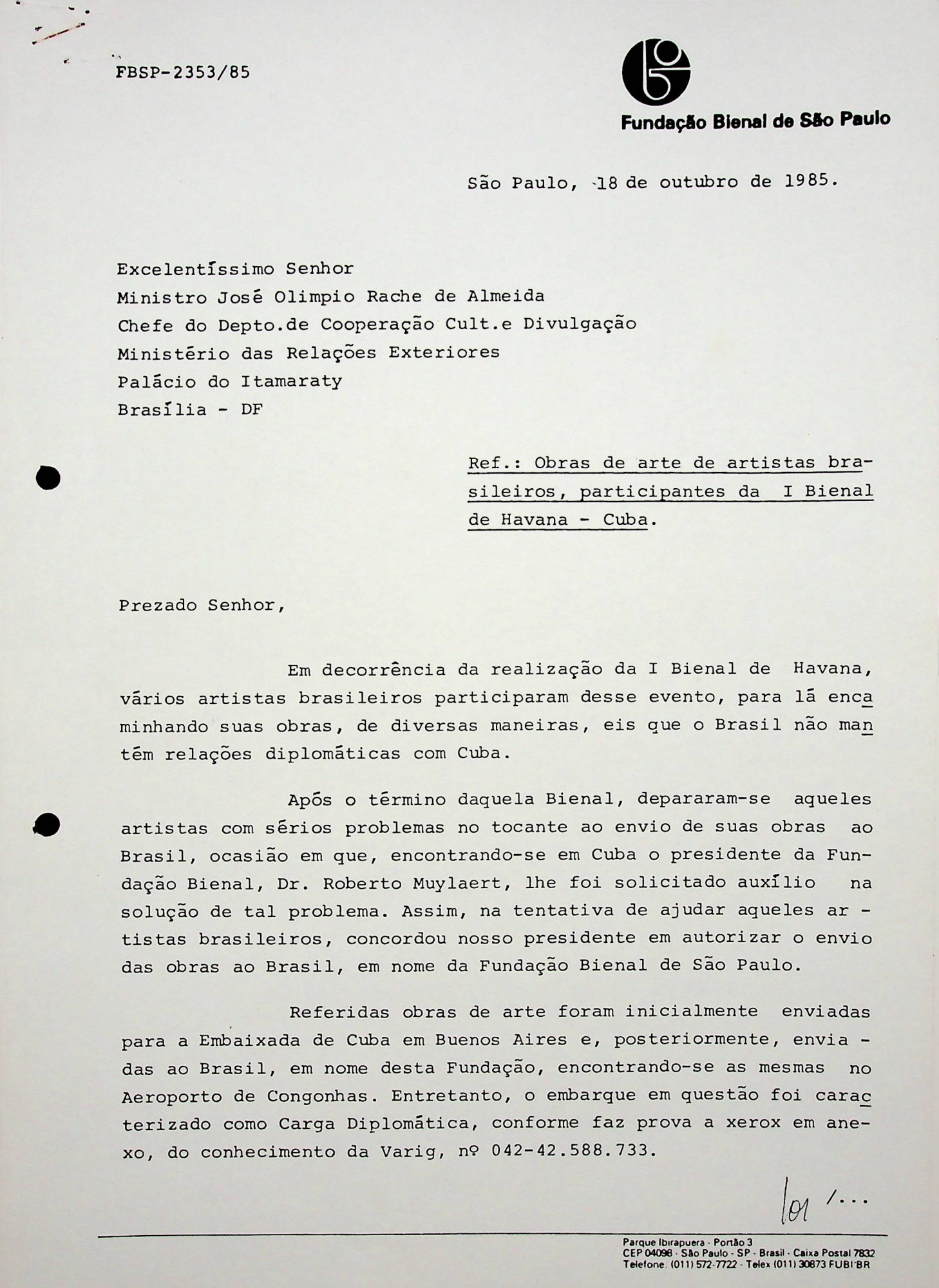

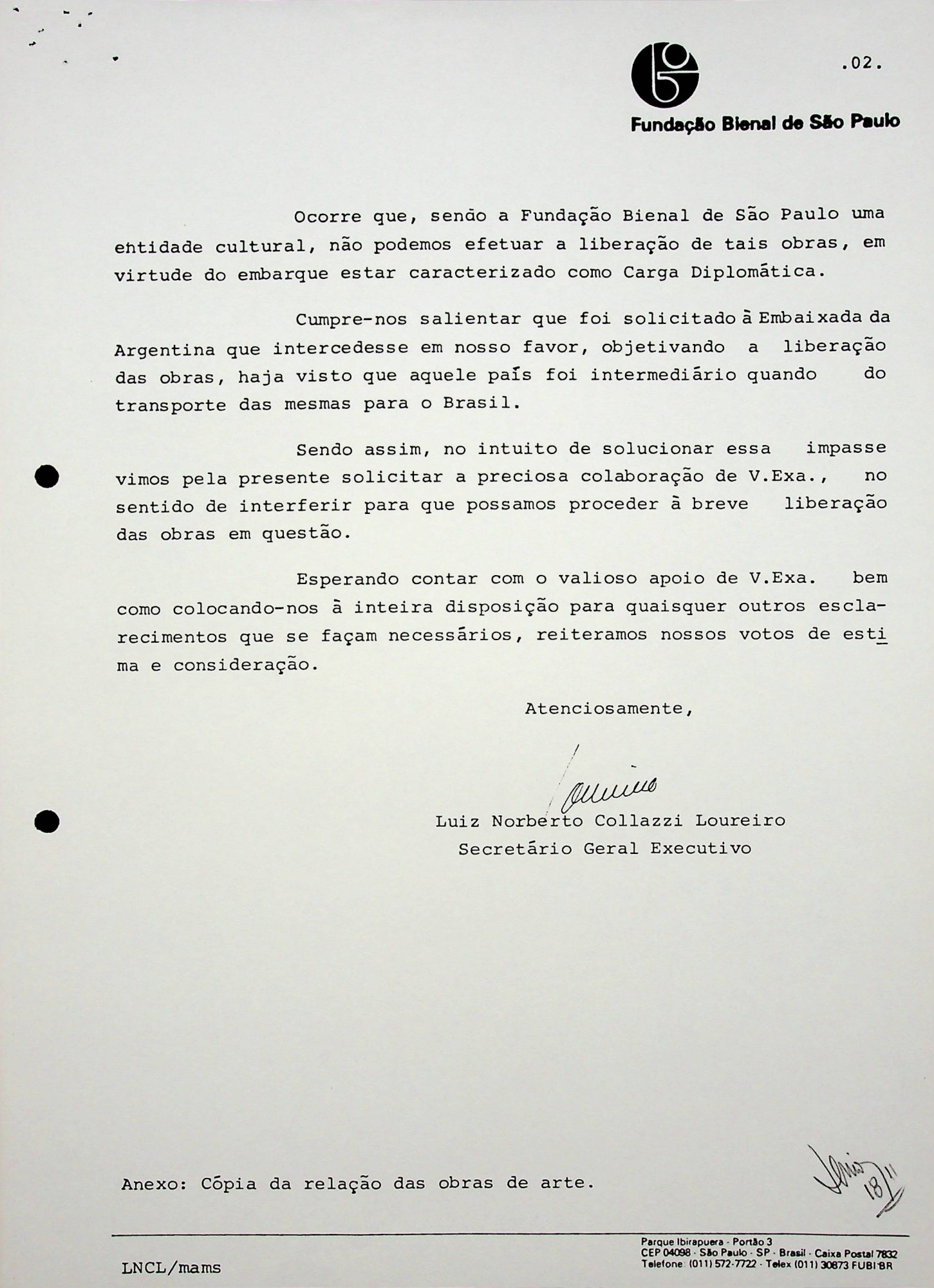

Once the event was over, the problem of returning the artworks arose, and the Biennial requested the collaboration of the São Paulo Biennial Foundation to carry it out. The documentation preserved in the Wanda Svevo Historical Archive attests that the FBSP negotiated with Itamaraty (Ministry of Foreign Affairs) in the return of the artworks that the Brazilian artists “in various ways” had sent to the Havana Biennial, and whose return journey involved a changeover in Buenos Aires before arriving at Congonhas Airport (Fig. 6 and 7).35

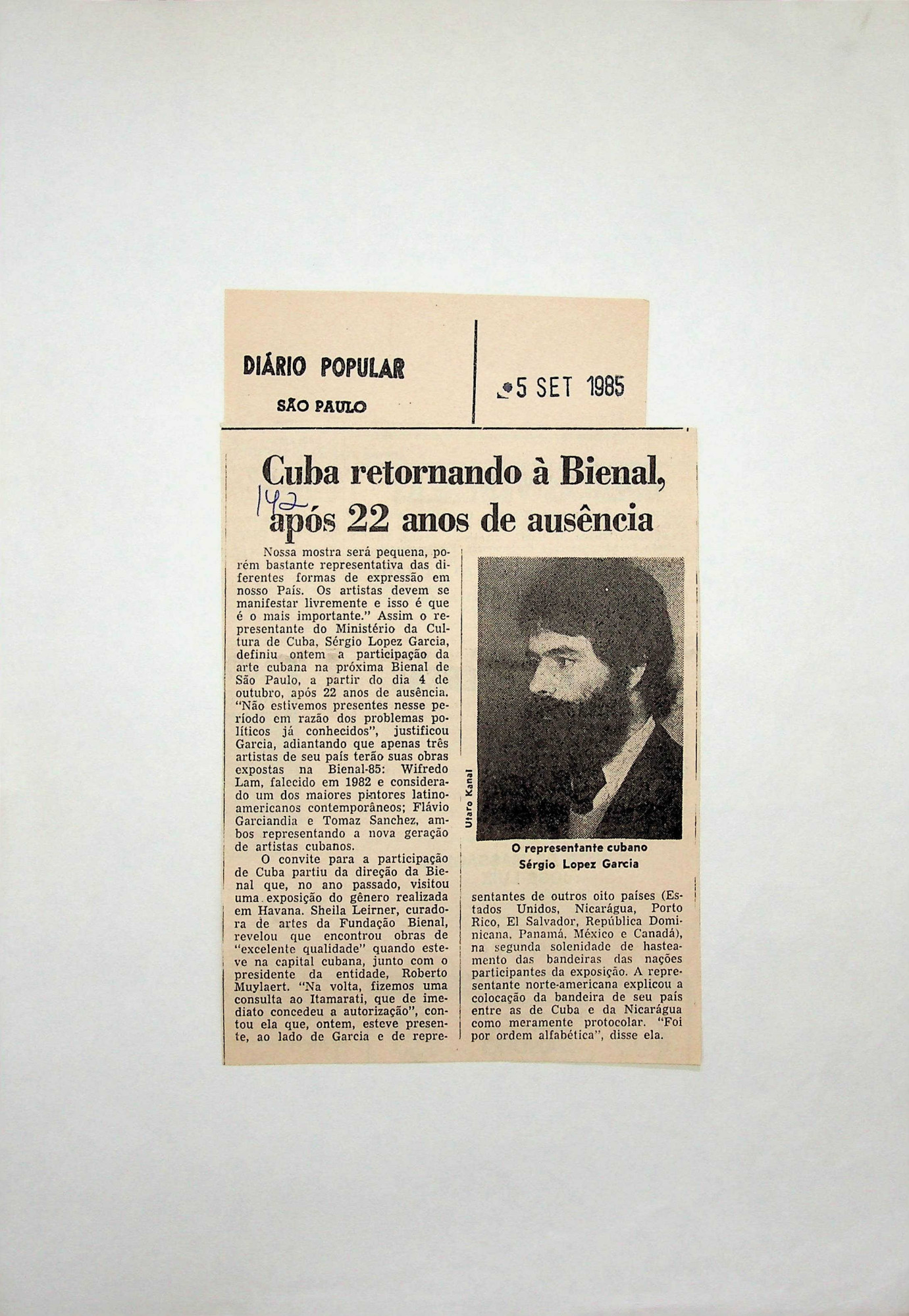

The letter with which Llilian Llanes expresses her gratitude to Roberto Muylaert for his collaboration begins with the sentence: “Finally the artworks of Lam arrive in São Paulo.”36 Indeed, the impact of the paintings of Wifredo Lam exhibited in Cuba was so great that the delegation of the São Paulo Biennial asked for a solo exhibition to be held in the following edition (1985).37 This led to the exhibition of some forty works by Lam (paintings, drawings, and engravings) at the historic nucleus. The Brazilian press echoed the return of Cuba to the Biennial after twenty-two years with articles such as Cuba volta, com Lam, à Bienal [Cuba returns, with Lam, to the Biennial] or Cuba retornando à Bienal, após 22 anos de ausência [Cuba returns to the Biennial after an absence of 22 years] (Fig. 8).38 Finally, the admiration for Lam’s artistic production is also evident in the articles published about the First Havana Biennial: Sheila Leirner defines the exhibition of Wifredo Lam in the National Museum of Fine Art as “beautiful” and Aracy Amaral as “magnificent and essential.”39

Revisiting the maps and examining the one concerning the press of the Second Biennial reveals that France and Mozambique were among the primary places where articles were written (three in both cases). Moreover, in the map that also shows the foreign public, in the case of France, there is a connection between Paris and Havana.

Indeed, personalities from the Parisian art community—such as the critics and art historians Pierre Gaudibert, Hélène Lassalle, Giovanni Joppolo, Jean-Louis Pradel, and Pierre Restany—visited the Havana Biennial.40 On their return to Paris, they wrote their impressions of the event in magazines such as Opus International or Cimaise, thereby giving this biennial an international projection.41 Gaudibert and Restany will return to Cuba for the third edition (1989), and, in addition to strengthening the relations established during the first trip, they will continue to write and disseminate their reflections on the Biennial in the press and specialised magazines.42

By contrast, in the case of Mozambique, the articles featured in the press mainly comprise reviews that address the participation of this country in the Biennial, highlight the election of artist Malangatana Ngwenya as a member of the jury and refer to the on-site activities of Gerardo Mosquera.43 Thus, in this instance, the analysis of the maps and related documentation directs our attention back to a strategy used by the Wifredo Lam Centre to organise the Biennial: the research trips.

Indeed, from the outset, the Wifredo Lam Centre understood the need for and importance of carrying out research in situ to gain first-hand knowledge of the art scene in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America and to overcome the impasse of the official (and diplomatic) selection of artists by the institutions of each country. Since the Ministry of Culture did not financially support the research trips, two mapping strategies were implemented: invitations to events abroad and cultural agreements with Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, which established a commitment to exchange exhibitions. The Wifredo Lam Centre prepared and offered exhibitions to these countries on the condition that curators accompanied them.44

By this procedure, in 1986, Gerardo Mosquera travelled to Angola and Mozambique for the exhibition África dentro de Cuba [Africa inside Cuba]. These trips facilitated his engagement with the local art scene and allowed him to select artists for the Biennial.45 In addition, during his stay in Mozambique, he gave lectures on topics related to the exhibition, the visual arts in Cuba, and the project of the Havana Biennial.46 Hence, the research trip also proved an opportunity to present and promote the project of the Wifredo Lam Centre.

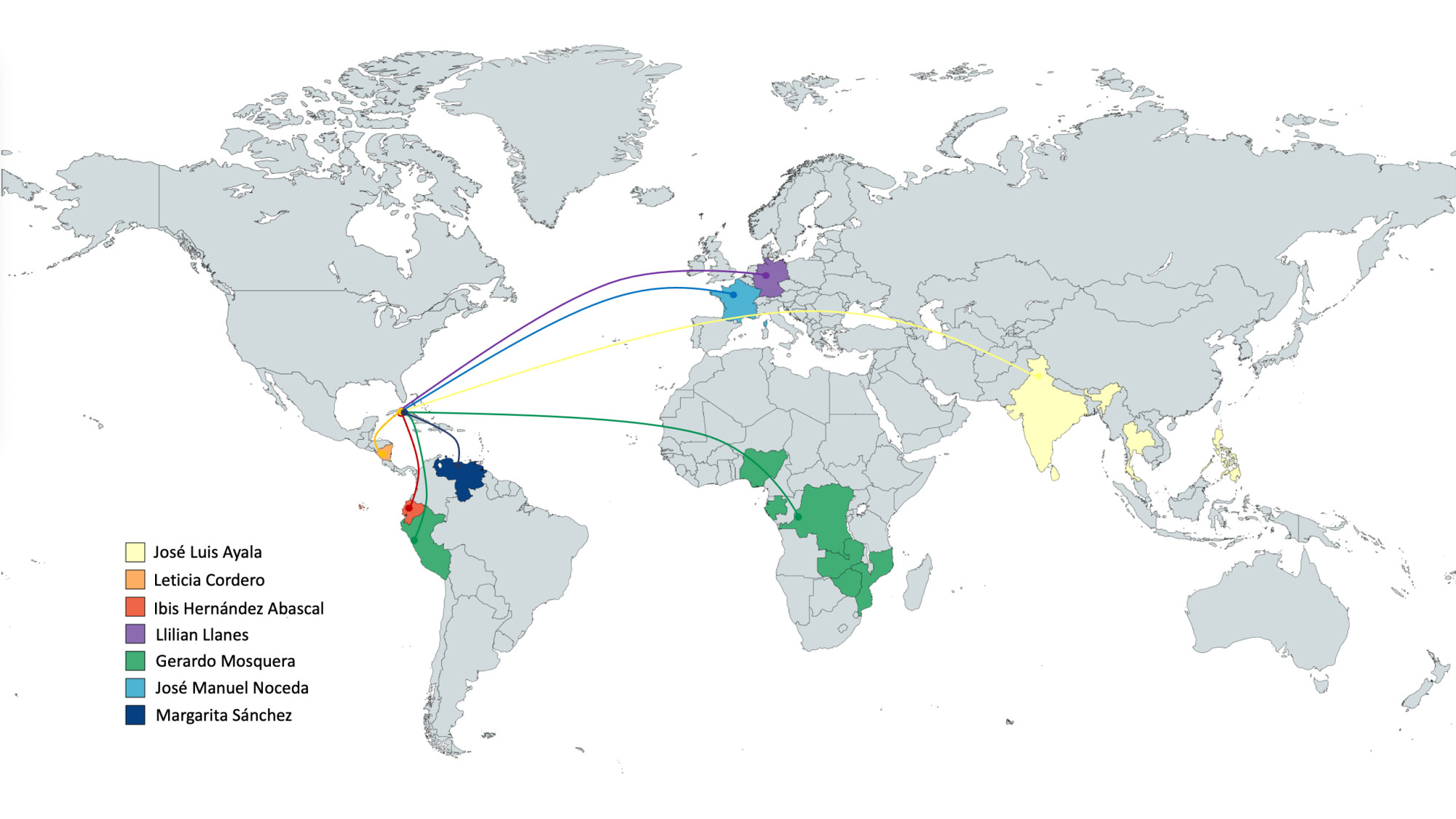

The research trips continued with the organisation of the third edition. Members of the Wifredo Lam Centre team travelled to various latitudes: Gerardo Mosquera returned to Africa (Gabon, Zaire, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, and Nigeria), as well as visiting Peru, while José Luis Ayala travelled to Asia (Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and India). Latin America was covered by Margarita Sánchez, Ibis Hernández Abascal, and Leticia Cordero, who were in Venezuela, Ecuador, and Nicaragua, respectively. In Europe, José Manuel Noceda was present in France, while Llilian Llanes was in Germany (Fig. 9).47 Following these trips, meetings were organised where curatorial team members presented the material collected and a project for the Biennial, which was submitted for collective discussion.48

Mapping circulations

“Cuban experts travelled through these regions, selecting artworks and artists to avoid official shipments of ‘diplomatic art’.”49 This is how Pierre Gaudibert described the importance of the research trips in Le monde diplomatique. This work enabled the “creative effervescence” of the artistic practices of the Third World to be shown, and the Havana Biennial affirmed itself as “one of the main poles of meeting, encounter and exchange between artists from all over the planet.” Finally, the article referred to some new features of the exhibition model, such as eliminating awards.

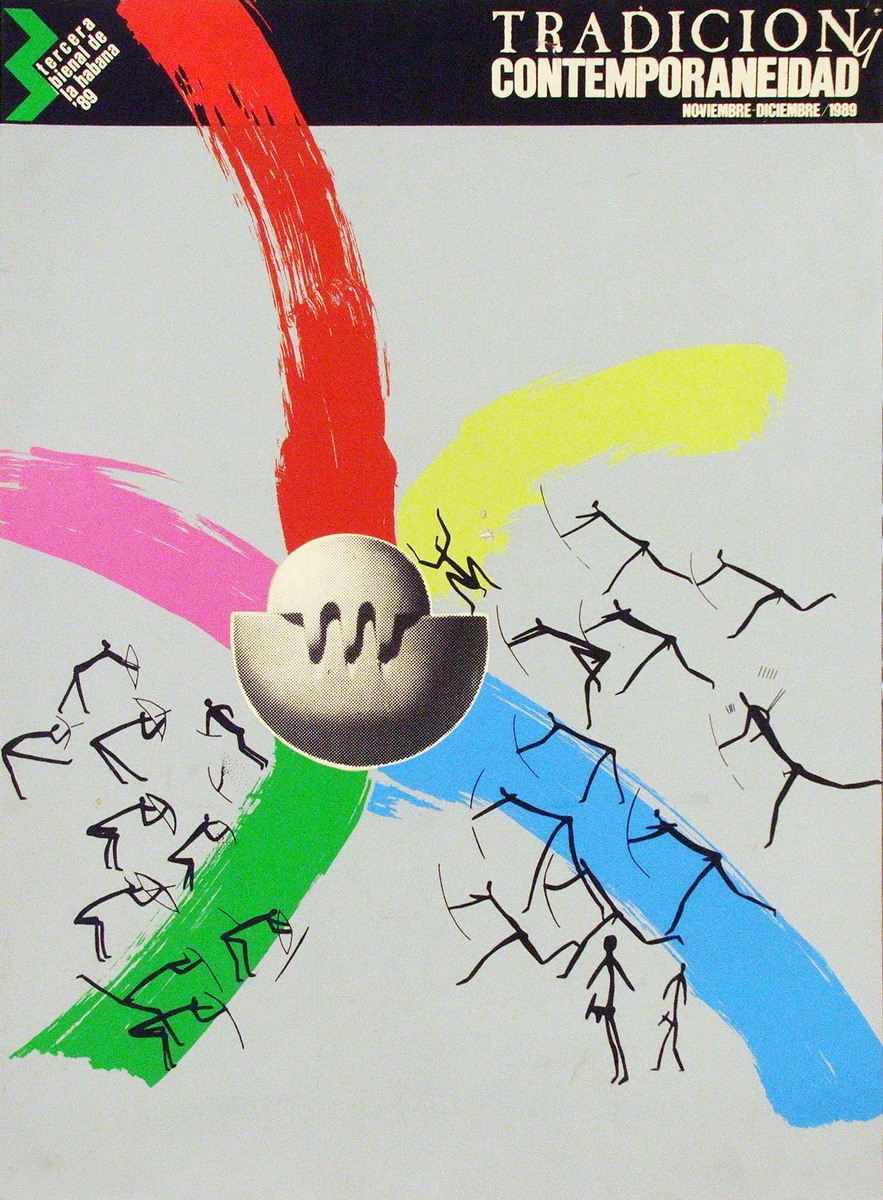

In fact, in the third edition, the Biennial eliminated the competitive character, abandoned the division by nationalities, and established a thematic axis of reflection (Tradición y contemporaneidad en el arte del Tercer Mundo [Tradition and Contemporaneity in Third World Art], Fig. 10). The theme interconnected and interrelated the sections of its triadic structure (exhibitions, workshops, and theoretical meetings). Therefore, the Biennial was conceived integrally: the exhibitions were to provide the visual material for a first level of analysis, configured as an essay to exhibit a theme and multiple points of view. The workshops were intended to encourage exchange between artists from different countries, to contribute to the enrichment of Cuban artists, and to facilitate public participation. Finally, the theoretical meetings were intended to enrich the conceptual character of the event and provide the basis for future debates.50

The study of the theoretical meetings allows us to see how networks crisscrossed it articulated around common projects and shared horizons, which refer us to the reality of biennials in the seventies. Among the participants in the theoretical meetings were personalities such as Mirko Lauer and Juan Acha, who belonged to the network of intellectuals who believed the biennial model needed to be transformed.51 In the previous decade, they were involved in two important initiatives that attempted to transform this model: the First Latin American Biennial of São Paulo (1978) and the First Colloquium of Non-Objectual Art and Urban Art (Medellín, 1981).

A point of interest is how these events and theses were held there, and their reflections were present in the theoretical meetings in Havana. Throughout his intervention, Mirko Lauer referred to the First Latin American Biennial of São Paulo as “the most direct antecedent of this Havana Biennial.”52 Meanwhile, Juan Acha pointed out that biennials devoted exclusively to the exhibition of artworks were meaningless and that it was essential to incorporate the discursive component.53 These statements allow us to weave maps of relationships with the two events indicated and to trace the circulation of currents of thought.

In terms of model, the project for the First Latin American Biennial of São Paulo envisaged the choice of a theme (Mitos e Magia [Myths and Magic]), to which the exhibition and symposium were to be attached, along with the elimination of competition and the abandonment of national representations. Although this last aspect was not implemented because the countries preferred to [maintain pavilions, it] is worth highlighting the will to superimpose a conceptual structure on the traditional geopolitical logic of [national] representations.54 Furthermore, the biennial was criticised for [failing to establish a real dialogue between the exhibition and the symposium.]55

In 1981, Juan Acha, who had directed that symposium, organised the First Colloquium of Non-Objectual Art and Urban Art in Medellin. It was divided into two interrelated sections: a theoretical meeting, with the participation of art historians and critics such as Mirko Lauer, and an exhibition presenting artists’ proposals. Throughout the event, activities and public discussions were privileged since the aim was that artistic production and critical thinking nurtured each other. [The]{.mark} Colloquium was thus a further attempt to imagine alternatives to the conventional exhibition model, bringing together theory, practice, and experience.56

Indeed, at the opening of the Colloquium, Juan Acha stated that “it is no longer possible to hold biennials or exhibitions without a guiding idea or a research purpose.”57 In an article of the same year, he expressed his ideas on the model, sustaining the need for “biennials of research.” The biennial theorised by Acha envisaged the choice of a theme by “one or several critics,” who were to conduct “fieldwork research” and select the artworks. This model was based on the discursive component (a symposium that would conceptually accompany the biennial) and did not contemplate competition.58

This map of relations intensifies if the considerations of Pierre Restany on the IV Medellin Biennial are included, which was taking place in parallel to the Colloquium and sought to be a space for the exhibition of “universal art.”59 The French critic questioned its format, approach, and purpose, asserting that a biennial organised in this way is no longer productive anywhere in the world. In particular, he questioned the interest of this Biennial in strengthening ties and making comparisons between Latin America and the West. He suggested redirecting its attention to Asia and Africa, establishing a direct connection between their countries and those of Latin America. Restany then proposed the creation of a “Biennial of Marginality,” a Third World biennial, understanding the Third World as a methodological concept from which to reflect on the difficulty of being.60

It is interesting to note that the Third World as a concept was one of the points addressed by Restany in his lecture at the theoretical meetings of the Third Havana Biennial.61 This point is taken up again in the interview he gave to the magazine Arte en Colombia, during which he recalls the proposal of a “biennial of difficult identities” made in Medellin eight years earlier.62

Biennial Adventure

“My dear Pierre: Once again I am involved in the adventure of the Biennial. Once I have finished the document in which we explain what we want to do in the next edition, I am sending it to you because, as ever, you have been in my thoughts.” So begins the letter written by Llilian Llanes in 1996. It continues: “Many of the things we talked about the last time we met in Havana have helped me to plan this Biennial. I hope that as always you will accompany me and give me your spiritual support, which I need so much.”63

“The last Biennial [1994] saw an important qualitative leap,” the response from Restany asserted. He went on to include some considerations about the new generation of young artists from the Third World and how the art that was being created there “illustrates the beginning of a revolution of taste and judgement in our World.” The French critic closed the letter by stating that he would do “everything possible” to travel to Havana for the Sixth Biennial (1997) (but, if he failed, he would be “wholeheartedly committed to this prodigious undertaking”). He praised the work done: “thanks to your perseverance, the Cuban Biennial is acquiring its true ethical dimension, that of the emergence of the periphery in the splendour of its expressive autonomy.”64

These letters testify to the longevity of the professional and personal relationship between Restany and Llanes and the exchange of ideas about the Habanero event. According to Memorias. Bienales de La Habana 1984–1999, the exchanges of 1986 proved fruitful when Restany, together with other critics and art historians from Paris, visited the Second Biennial. Subsequently, Llanes began to analyse “the basic strategies of each edition of the Biennial” with the assistance of Restany. In this Memorias, the director of the Wifredo Lam Centre also explains that, during a moment of reflection on the exhibition model of the biennials, there was an article by Restany that caught her attention and gave her “many ideas about what an event of this nature should be.”65

The reflections on the model began after the first edition, so much so that she herself, who had just taken over the direction of the Wifredo Lam Centre, started research on “the problematics of biennials.”66 The research allowed her to understand that “the patterns of the biennials were obsolete” and that it was necessary to look for a “new organisational and structural formula” for the Havana Biennial.67 This research continued after the closure of its second edition. To ascertain opinions about the event, the Wifredo Lam Centre analysed what had been written about this edition on a national and international level. The information thus gathered complemented what was already available and derived from previous research and conversations with historians and artists who had visited the Biennial. The study of these materials corroborated the previous idea of reconsidering the exhibition model formerly adopted.68

It is worth noting that 1986 was when Havana was already beginning to experiment with the exhibition model. Indeed, although this edition retained the competitive approach and the division by country, it had been organised as a constellation of events.69 However, still lacking a thematic axis, the Biennale had limited itself to compilation and display, presenting a panoramic view of the artistic production of the Third World. Yet, it had not established communication and interconnection among its sections, including exhibitions, workshops, and theoretical meetings. Since its objective was to promote a debate on art, to question rather than merely to illustrate, this structure necessitated being “filled with content.” This was achieved in 1989 by establishing the theme, the object of reflection on which to base all its sections.70

The theoretical meeting of this third edition demonstrated the convergence of personalities in Havana who, hailing from various parts of the world, were demanding and promoting the transformation of the biennial model. Throughout the article, the characteristics that the “research biennial” theorised by Juan Acha should have been expounded upon, thereby revealing a series of elements in common with the model of the Third Havana Biennial. It is worth noting that some of these characteristics were already present in the structural reforms of the model indicated by Pierre Restany in the mid-sixties after he visited the VIII São Paulo Biennial (1965).71 An example is the adoption of a central theme chosen by an international commission of specialists (in the “research biennial” by “one or more critics”).72 Another aspect is the choice of artists and, consequently, the exhibition structure, without considering nationality principles but adding artists’ production to the designated theme. In the case of the Third Havana Biennial, artworks were not exhibited by countries but rather by “thematic affinities” around the object of reflection.73

The reflections of Restany circulated in newspapers and magazines in Brazil and Italy, as well as in France. Meanwhile, the ideas of Acha were published mainly in Colombia and, thanks to his participation in the First Latin American Biennial of São Paulo, were also recognised in Brazil.74 The analysis of these currents of thought has exposed intellectual networks interconnecting the Havana Biennial with other artistic events in Latin America, such as the Latin American Biennial or the Colloquium of Non-Objectual Art and Urban Art. In contrast, the quantitative study of the press coverage of the first two editions of the Caribbean biennial, coupled with its geospatial visualisation, has revealed a considerable increase in publications from the first to the second editions, evidencing areas where the Biennial garnered increased attention and has even allowed highlighting the organisational strategies of the event or the work of personalities such as Gerardo Mosquera. Finally, by combining these data with those of the public, it has been possible to identify the existence of a São Paulo–Havana axis, which led to the return of Cuba in the Brazilian biennial.

Thus, the maps again refer to the circulation of ideas and personalities. The analysis of these circulations, in conjunction with the materials produced by the exhibition, has woven a dense network of institutional, professional, and personal relationships. This is the case with intellectuals such as Mirko Lauer and Juan Acha, who found a new space for reflection in the Havana Biennial, or the enduring relationship between Llilian Llanes and Pierre Restany, as evidenced by the correspondence they exchanged. This article has thus made these relationships visible and, in doing so, has demonstrated the interconnectedness between the institutional and the personal. Indeed, the transformation of the biennial model that was taking place during those years was a joint but delocalised effort in which several institutions took part and which was also conveyed by professional and personal connections.

Finally, in this act of remembering on paper, the questioning and interpretation of the “objects of times” produced by the Havana Biennial has offered an approach to this event that, instead of concentrating solely on the exhibition space, focuses on the events and dynamics that unfolded “around” the biennial, in turn exerting influence on the configuration of the exhibition space itself. In this way, other places, individuals, and temporalities emerged whose knowledge not only offers new “entry points” to the event under analysis but also, in my perspective, provides tools to perceive and comprehend the event itself distinctly and more broadly.

-

I Bienal Latino-americana de São Paulo. 40 anos depois (São Paulo: Centro Cultural de São Paulo, 2019). ↩

-

Cecilia Alemani, “Introduzione / Introduction,” in Le muse inquiete. La Biennale di Venezia di fronte alla storia/The Disquieted Muses. When La Biennale di Venezia meets history (Venice: La Biennale di Venezia, 2020), 25–27. ↩

-

Reesa Greenberg, “‘Remembering Exhibitions’: From Point to Line to Web,” Tate Papers 12 (2009). Greenberg uses the gerund (remembering exhibition) because “it is ambiguous, confounding subjective and objective acts of memory and suggesting an oscillation between the two.” ↩

-

Yu Jin Seng, “Restaging critical exhibitions: the will to archive/memorialise/subjectivity,” World Art 10, no. 2–3 (2020): 219–222. ↩

-

Lecture by Diana Toccafondi in Archives and Exhibitions. Proceedings of the Second International Conference Archives and Exhibition (Venice: La Biennale di Venezia, 2014), 175–187. ↩

-

On features relating to network formation, development and structures, see J. R. Mc Neill and William Mc Neill, Las redes humanas. Una historia global del mundo, Barcelona, Crítica, 2004, 1–6. On exhibitions as places of meeting see Olga Fernández López, Exposiciones y comisariado. Relatos cruzados (Madrid: Cátedra, 2020), 13–18. ↩

-

Llilian Llanes, Memorias. Bienales de La Habana, 1984–1999 (Havana: Arte Cubano Ediciones, 2012), 204–205 and 242–243; Die 5. Biennale von Havana: Kunst, Gesellshcaft, Reflexion: eine Auswahl ([Aachen: Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst, 1994). The exhibition took place from September 15 to December 11, 1994.]{.mark} ↩

-

The Havana Biennial has been defined as an “innovative moment” in the history of biennials by several historians. For example, Rafal Niemojewski defines it as the first contemporary biennial, while Rachel Weiss highlights its third edition for its aspiration to conduct, in terms of content and impact, global research and to do so from outside the European and North American art system. Rafal Niemowjeski, “Venice or Havana: A Polemic on the Genesis of the Contemporary Biennial,” in The Biennial Reader, ed. Elena Filipovic, Marieke Van Hal and Solveig Øvstebø (Ostfildern / Bergen: HatjeCantz Verlag / Bergen Kunsthall, 2010), 88–103; Rachel Weiss, “A Certain Place and a Certain Time: The Third Bienal de La Habana and the Origins of the Global Exhibition,” Making Art Global (Part 1) The Third Havana Biennial 1989, ed. Rachel Weiss (London: Afterall, 2011), 14–69. ↩

-

The Wifredo Lam Centre was created in 1983 “to promote internationally the art work of artists from Asia, Africa, and Latin America, as well as of artists that struggle for cultural identity and that are related to those territories” (Gaceta Oficial de Cuba - Decreto No. 113, 1983). The First Havana Biennial (1984), organised by the Cuban Ministry of Culture, was dedicated to Latin America and the Caribbean; the second edition (1986), already organised by the Wifredo Lam Centre, opened up to Africa, Asia and the Middle East. Throughout its first two editions, the Biennial remained anchored to the old biennial model, introducing, however, changes that gradually led to the establishment of the model inaugurated with the third edition (1989). ↩

-

Reesa Greenberg, Bruce W. Ferguson, and Sandy Nairne (eds.), Thinking about Exhibitions (London and New York: Routledge, 1996). The decade of the 1990s also saw the publication of Bruce Altshuler, The Avant-garde in Exhibition: New Art in the 20th Century (Berkley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994) and Bernd Klüser and Katharina Hegewisch, L’art de l’exposition: une documentation sur trente expositions exemplaires du XXe siècle (Paris: Éditions du Regard, 1998). ↩

-

Catalina L. Imizcoz, “Extending the Study of Exhibitions across Geographies,” Caiana 1, no. 10 (2017): 80–95. The author identifies six categories: linear, tangential, supportive, concentrated, alternative, and experimental. On exhibition studies see also Yaiza Hernández Velázquez, “Who Needs ‘Exhibition Studies?’,” in Critical Museology: Selected Themes Reflections from the William Bullock Lecture Series (Mexico City: MUAC–UNAM, 2019), 286–302. ↩

-

Bruce Altshuler, Salon to Biennial. Exhibitions that Made Art History, 1863–1959 (London and New York: Phaidon, 2008); Bruce Altshuler, Biennials and Beyond. Exhibitions that Made Art History, 1962–2022 (London and New York: Phaidon, 2013). ↩

-

In the case of biennials see Rachel Weiss, Making Art Global (Part 1). The Third Havana Biennial 1989 (London: Afterall Books, 2011) and Lisette Lagnado (ed.), Cultural Anthropophagy. The 24^th^ Bienal de São Paulo 1998 (London: Afterall Books, 2015). ↩

-

Charlotte Klonk, Spaces of Experiencie. Art Gallery Interiors from 1800 to 2000 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009); Isabel Tejeda, El montaje expositivo como traducción (Madrid: Trama Editorial, 2015); Mary Anne Staniszewski, The Power of Display, A History of Exhibition Installations at the Museum of Modern Art (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1998). ↩

-

Olga Fernández López, Exposiciones y comisariado. Relatos cruzados (Madrid: Ediciones Cátedra, 2020). ↩

-

Bruce W. Ferguson Bruce, “Exhibition Rhetorics: material speech and utter sense,” in Thinking about Exhibitions, eds. Reesa Greenberg, Bruce W. Ferguson, Sandy Nairne (London and New York: Routledge, 1996), 126–136. ↩

-

Fernández López, Exposiciones y comisariado. Relatos cruzados, 13–18. ↩

-

Paula Barreiro López, “Art History and the Global Challenge: A Critical Perspective,” Artl@s Bulletin 6, no. 1 (2017): 48–57; Monica Juneja, “Global Art History and the ‘Burden of Representation,” in Global Studies: Mapping Contemporary Art and Culture, eds. Hans Belting, Jakob Birken, and Andrea Buddensieg (Ostfildern: Hatje Canitz Verlag, 2011), 274–297. ↩

-

Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann, Chaterine Dossin and Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel “Introduction: Reintroducing circulations: Historiography and the Project of Global Art History,” in Circulation in the Global History of Art, eds. Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann, Chaterine Dossin and Béatrice Joyeux-Prune (London / New York: Routledge, 2015), 1-22. ↩

-

Michel Espagne, “La notion de transfert culturel,” Revue Sciences/Lettres, no. 1 (2013): 1-9. ↩

-

Michel Werner and Bénédicte Zimmermann, “Penser l’histoire croisée: entre empirie et réflexivité,” Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales, no. 1 (2013): 7-36. ↩

-

On the construction of new cartographies of artistic practices in their collaborations and tensions with political practices during the Cold War see Paula Barreiro López (ed.), Atlántico Frío. Historias transnacional del arte y la política en los tiempos del telón de acero (Madrid: Brumaria, 2018). ↩

-

Maps that are the result of a combination of a quantitative analysis and geospatial visualisation of the data. ↩

-

Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, “ARTL@S: A Spatial and Trans-national Art History Origins and Positions of a Research Program,” Artl@s Bullettin 1, no. 1 (2012): 9–25. ↩

-

A separate mention should be made of trans_action: The Accelerated Art Worlds, 1989–2011 (Stewart Smith, Robert Gerard Pietrusko, and Bernd Lintermann, 2011), a project that describes the temporal and spatial development of biennials and art markets. On the use of maps see, for example, the section “Mapping. The Biennials and New Art Regions” in the exhibition The Global Contemporary. Art World After 1989 (ZKM / Museum of Contemporary Art, 17.09.2011–05.02.2012) or the study conducted by OnCurating in 2018. See “Room of Histories,” in The Global Contemporary and the Rise of New Art Worlds, eds. Hans Belting, Jakob Birken, and Andrea Buddensieg (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2013), 50–151. Ronald Kolb and Shwetal A. Patel, “Survey review and consideration,” OnCurating 39 (2018), 15–34. ↩

-

Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, “Introduction: Do Maps Lie?,” Artl@s Bulletin, vol. 2, no. 2 (2013): 4 – 6. ↩

-

Miriam Kienle, “Between Nodes and Edges: Possibilities and Limits of Network Analysis in Art History,” Artl@s Bulletin, vol. 6, no. 3 (2017): 5-9. ↩

-

Joyeux-Prunel, “ARTL@S: A Spatial and Trans-national Art History Origins and Positions of a Research Program.” ↩

-

Olga Fernández López, “Comisariado y exposiciones: perspectivas historiográficas,” in Exit Book: revista de libros de arte y cultura visual 17 (2012): 52–69. For many decades Art History has been based on artists and their artworks. The exhibition was conceived as an instrumental element for the presentation of artworks, a mere container of the latter. This way of seeing has meant that there was no interest in documenting the exhibition. Interest put into artists and their production has meant that it was their artworks (and not the relationship that the latter established in space) that were photographed and reproduced in catalogues, magazines, and newspapers. Likewise, the exhibition was absent from the critical reviews, as these generally referred to the artworks exhibited. This [tendency]{.mark} has only recently started to reverse as a result of the increasing interest in exhibitions. ↩

-

This analysis has been carried out on the basis of the documentation preserved in the Archive of the Wifredo Lam Centre. The corpus of documents used includes reviews and articles in international newspapers and magazines. The information relating to the foreign public comes from the Memorias. Bienales de La Habana, 1984–1999 by Llilina Llanes and has been complemented with documentation found in the Wanda Svevo Historical Archive—São Paulo Biennial Foundation. The data has been dumped and processed in MoDe(s) Database, which belongs to the International Research Platform Modernidad(es) Descentralizada(s). As for the documentary corpus, it must be said that it is extensive and constitutes a good working basis for a first study, but it cannot be considered complete. ↩

-

The reasons behind these variations are multiple and interconnected: an increase in the number of participating countries, a greater global awareness of the project of the Wifredo Lam Centre, or even a precise historical moment of the biennial phenomenon. ↩

-

In Memorias. Bienales de La Habana, 1984–1999 (57–59), Llanes states that Mario Barata and Leonor Amarante were also there. I have not been able to verify the nature of this trip, as they do not appear among the members of the delegation to the São Paulo Biennial. ↩

-

Telegram from Lupe Velis (International Relations, Ministry of Culture of Cuba) to Luis Villares (São Paulo Biennial Foundation), February 23, 1984 (AHWS - FBSP, 01-07738); Telegram from Nina Hokka (Executive Secretary of the Presidency, São Paulo Biennial Foundation) to Lupe Velis (International Relations, Ministry of Culture of Cuba) and Marcia Leiseca (President, Organising Committee 1 Havana Biennial), São Paulo, February 28, 1984 (AHWS - FBSP, 01-07738). The telegram informs of the change of Board of Directors of the São Paulo Biennial Foundation, indicates the new members and requests their participation in the inauguration. ↩

-

Llanes, Memorias. Bienales de La Habana, 1984–1989, 37–42. ↩

-

Letter from Luiz Norberto Collazzi Laureiro (Executive General Secretary, São Paulo Biennial Foundation) to José Olimpo Rache de Almeida (Head of the Department of Cooperation and Culture, Ministry of Foreign Affairs), São Paulo, October 18, 1985 (AHWS - FBSP, 01-07536). ↩

-

Letter from Llilian Llanes (Director, Wifredo Lam Centre) to Roberto Muylaert (President, São Paulo Biennial Foundation), Havana, August 19, 1985 (AHWS – FBSP, 01-07997). Llanes was the director of the Wifredo Lam Centre between 1984 and 1999. ↩

-

The invitation was formalised after their having admired the artworks of Lam in Havana. The article by Sheila Leirner on the First Havana Biennial (see note 40) illustrates the room dedicated to Lam at the National Museum of Fine Arts, which was not part of the Biennial. Cfr. Telephone conversation with Margarita Sánchez Prieto (Curator, Wifredo Lam Centre), February 19, 2023. ↩

-

“Cuba volta, com Lam, à Bienal,” Jornal do Brasil, March 26, 1985; “Cuba retornando à Bienal, após 22 anos de ausência,” Diário Popular, September 5, 1985. Another article on the return of Cuba published in the Brazilian press is “A arte cubana na Bienal,” Jornal da Tarde, September 17, 1985. The Cuban press also celebrates it with “Participará Cuba en la 18va. Bienal de São Paulo,” Granma, August 9, 1985 (AHWS – FBSP, caixa 53). ↩

-

Sheila Leirner, “Havana, Bienal distante da abertura,” O Estado de São Paulo, June 3, 1984 (ACWL, I Bienal 1984); Aracy Amaral, “Bienal de Havana, um balanço positivo,” Folha de S. Paulo, June 12,1984 (IEB – USP, AAA-AA-119). ↩

-

A large group of Paris-based Latin American artists also travelled to Havana, both as public and as participants in the event. See Jean-Louis Pradel, “Quand le Paris latino-américain se déplace à La Havane,” L’evenement du jeudi, February 12–18, 1987, 86 (ACWL, II Bienal, 1986). ↩

-

Giovanni Joppolo, Lasalle Hélène, “Premiere Esquisse d’un recentrement de la diaspora africaine,” Opus International 194 (1987): 14–17 (ACWF, II Bienal, 1986); Restany, Pierre, “Bienal de La Habana. Cuba, Sí Cuba, no Cuba Libre,” Cimaise, year 34, no. 187 (1987): 2–4. ↩

-

Pierre Gaudibert, “Por un métissage culturel,” Le monde diplomatique, February, 1990 (MAM-ARCH-APG-EC); “La Bienal del Tercer Mundo. Entrevista a Pierre Restany,” Arte en Colombia 43 (1990): 56–58. ↩

-

“Bienal de Havana já em preparação,” Domingo, April 6, 1986; “Malangatana no jurí da Bienal de Cuba,” Domingo, May 4, 1986; “RPM participa,” Noticias, May 5, 1986 (ACWL, II Bienal, 1986). Gerardo Mosquera was part of the curatorial team of the Wifredo Lam Centre. The curatorial team was formed after the first edition of the Biennial, when Llilian Llanes assumed the direction of the Wifredo Lam Centre. Other members of the team were José Luis Alaya, Leticia Cordero, Ibis Hernández Abascal, Nelson Herrera Ysla José Manuel Noceda, Margarita Sánchez, and Eugenio Valdés. ↩

-

Llanes, Memorias. Bienales de La Habana, 1984–1989, 79–81. ↩

-

The trip to Angola enabled Mosquera to become acquainted with the artistic production of Antonio Ole and Víctor Teixeira, both of whom were present at the Second Havana Biennial. In addition, a personal exhibition was dedicated to both in the third edition. Llanes, Memorias. Bienales de La Habana, 1984–1989, 83–84; tercera bienal de la habana ’89. Catalogo general (Havana: Centro de Arte Wifredo Lam / Editorial Letras Cubana, 1989): 242–247. ↩

-

According to the newspaper Noticias (Maputo), the conference activity of Mosquera was intense, as he gave lectures on the development of the plastic arts in Cuba; the project of the Wifredo Lam Centre and the second Havana Biennial; the African presence in Cuban culture; as well as Cuban cultural policy and its impact on arts. See “RPM participa.” ↩

-

For a detailed description of these research trips see Llanes, Memorias. Bienales de La Habana, 132–138. ↩

-

Through the research trips, the members of the curatorial team gradually specialised in geographical areas. ↩

-

Gaudibert, “Por un métissage culturel.” This article was translated into Spanish and published in the Cuban newspaper Granma two months after being published in France. See Pierre Gaudibert, “Por un mestizaje cultural,” Granma, April 29, 1990 (MAM-ARCH-APG-EC). All expressions in inverted commas are direct quotations, the translation of which is mine. ↩

-

Llilian Llanes, “Presentación,” tercera bienal de la habana ’89. CATALOGO (Havana: Editorial Letras Cubanas, 1989), 13–18; Cecilia Lida, “Entrevista a Lilian Llanes: memoria y resistencia en los inicios de la Bienal de La Habana,” Ramona 95 (2009): 11–15. ↩

-

In 1989, the theoretical meetings were divided into two sections: Tradición y contemporaneidad en la plástica del Tercer Mundo [Tradition and Contemporaneity in Third World Art] and Tradición y contemporaneidad en el ambiente del Tercer Mundo [Tradition and Contemporaneity in the Third World Environment]. Lauer and Acha participated in the first and second, respectively. Other participants were Geeta Kapur, A. Rashid M. Diab, Frederico Morais, Pierre Restany (art), and Sergio Magalhães, Fruto Vivas, Aly Sinon, Roberto Segre (environment). ↩

-

Mirko Lauer, “Notas sobre plástica, identidad y pobreza en el Tercer Mundo,” in Debate Abierto. Tradición y Contemporaneidad en la Plástica del Tercer Mundo (Havana: Centro de Arte Wifredo Lam, 1989), 19–27. ↩

-

Juan Acha, “Tradición y contemporaneidad en el ambiente del Tercer Mundo,” in Debate Abierto Tradición y Contemporaneidad en el Ambiente del Tercer Mundo (Havana: Centro de Arte Wifredo Lam, 1989), 3–16. ↩

-

The Latin American Biennial was organised by the Art and Culture Council (Conselho de Arte e Cultura—CAC), a consultative and normative organ, composed of critics, art historians, and artists. It was the organ responsible for the organisation of the biennials from 1975 to 1991. Its project for the Latin American Biennial foresaw a montage in four sectors (Indigenous, African, Eurasian, and métissage) under the theme of Mitos e Magia [Myths and Magic]. On this project, see Conselho de Arte e Cultura, “I Bienal Latino-Americana. Un evento histórico,” I Bienal Latino Americana de S. Paulo (São Paulo: Ministério das Relações Exteriores, Ministério da Educaçao e Cultura—Funarte, Secretaria de Cultura, Ciência e Tecnologia SP, Secretaria Municipal de Cultura—PMSP, 1978), 20–22. On the CAC, see Thiago Gil Virava, “Seis décadas da Fundação Bienal de São Paulo: um percurso arriscado,” in Bienal de São Paulo desde 1951, ed. Paulo Miyada (São Paulo: Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, 2022), 365–379. ↩

-

Frederico Morais, “Apêndice: I Bienal Latino-Americana de São Paulo,” in Artes plásticas na América Latina: do transe ao transitório, (Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1979), 62–65. ↩

-

For an analysis of this evento, see Imelda Ramírez González, Debates críticos en los umbrales del arte contemporáneo. El arte de los años setenta y la fundación del Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín (Medellin: Fondo Editorial Universidad EAFIT, 2012), 36–52; and Miguel A. López, Robar la historia. Contrarrelatos y prácticas artísticas de oposición (Santiago de Chile, Metales Pesados, 2017), 98-99. ↩

-

Text “Palabras del señor Juan Acha, Director del Primer Coloquio Latino-Americano sobre arte no-objetual, en la sesión de instalación del evento” (FR ACA PREST.XSAML03). ↩

-

Juan Acha, “Las bienales en América Latina de hoy,” Re-vista del arte y la arquitectura en América Latina de hoy 2, no. 6 (1981): 14–16. ↩

-

The IV Medellin Biennial was an attempt to reactivate the Coltejer Art Biennial (1968–1972). It sought to be a place for the exhibition of Latin American art and to favour the comparison with the artistic practices of the United States, Canada, Japan, and Europe. Detlef Michael Noack in 4a. Bienal de Arte Medellín Colombia (Medellin: Corporación Bienal de Arte de Medellín, 1982), n.p. ↩

-

Óscar Gómez P., “Bienal de Medellín. Opiniones—entrevistas I,” Arte en Colombia 16 (1981): 50; Cecilia Sredni de Birbragher, “Pierre Restany propone: La Bienal de la Marginalidad [Entrevista],” Arte en Colombia 16 (1981): 71–73. ↩

-

Pierre Restany, “Consideraciones generales sobre el arte y el Tercer Mundo,” in Debate Abierto. Tradición y Contemporaneidad en la Plástica del Tercer Mundo (Havana: Centro de Arte Wifredo Lam, 1989), 44–46. ↩

-

“La Bienal del Tercer Mundo. Entrevista a Pierre Restany,” Arte en Colombia 43 (1990): 56–58. ↩

-

Letter from Llilian Llanes to Pierre Restany, Havana, July 11, 1997 (FR ACA PREST TOP AML 031). Although the letter is dated 1997 in the heading, the information given, the stamp (indicating 18th July 1996 as the “date of departure”) and the response of Restany from the previous year (which refers to the letter of July 11), suggest that the letter is from 1996 and that there was a typing error. ↩

-

Letter from Pierre Restany to Llilian Llanes, Paris, August 31, 1996 (FR ACA PREST TOP AML 031). ↩

-

Llanes, Memorias. Bienales de La Habana, 1984–1999, 113 and 72, respectively. It has not been possible to identify the Restany article referred to. ↩

-

After the first edition, meetings were organised to analyse the results and the future of the Havana Biennial; among the issues discussed were the competitive character and the modality of selection of the artists. ↩

-

Llanes, Memorias. Bienales de La Habana, 1984–1999, 72. ↩

-

Margarita Sánchez Prieto, “III Bienal de La Habana. Tradición y contemporaneidad en el arte del Tercer Mundo,” La Bohemia, October 27, 1989 (ACWL, III Bienal 1989). ↩

-

In the second edition, the jury drafted a document with some considerations, for example, re-evaluating the competitive character and favouring participatory activities. ↩

-

Lida, “Entrevista a Lilian Llanes: memoria y resistencia en los inicios de la Bienal de La Habana,” 14–15. ↩

-

“Restany: Brasília, Bienal e Vanguarda [Entrevista],” Correio da manhã, September 25, 1965 (AWS – FBSP, caixa 28 – 031). ↩

-

Acha, “Las bienales en América Latina de hoy”, 14–16. ↩

-

Llanes, Memorias. Bienales de La Habana 1984–1999, 142–146. The display by “thematic affinities” was intended to provide visibility to elements of union and points of divergence in the artistic production of the participating countries, leaving behind a spatial arrangement that would inevitably prioritise one country over another. ↩

-

Acha, “Las bienales en América Latina de hoy,” 14–16; “Restany: Brasília, Bienal e Vanguarda [Entrevista]”; Pierre Restany, “VIIIème Biennale de São Paulo: comment va la cousine australe de Venise?,” Domus 432 (1965): 47–52; Pierre Restany, “São Paulo 1965: Calme Plat” (ACA – FPR, PREST.XSAML 17); Pierre Restany, “Biennales,” in L’avant-garde au XXème siècle, eds. Pierre Cabanne and Pierre Restany (Paris: André Balland, 1969), 110–119. ↩

Anita Orzes is a PhD candidate at the Universidad de Barcelona and the Université Grenoble Alpes. Her research deals with the biennial phenomenon and the transformation of its model with a special focus on transnational networks in the seventies and eighties.

She participated in the Theoretical Event of the 14th Havana Biennial (2021) and worked as a cultural mediator at the 53rd Venice Biennale (2009). She was a documentalist for the exhibition Caso de estudio. España. Vanguardia artística y realidad social: 1936–1976 (Institut Valencià d’Art Modern, 2018–2019). She holds an MA in Contemporary Art History and Visual Culture (Universidad Complutense de Madrid/Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia) and a BA in Conservation of Cultural Heritage (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia)]

This paper is the result of research in the framework of an FPI contract (PRE2018-085848) as well as the research project MoDe(s)—Modernidad(es) Descentralizada(s). Arte, política y contracultural en el eje transatlántico durante la Guerra Fría/Decentralized Modernities. Art, Politics and Counterculture in the Transatlantic Axis during the Cold War (Universidad de Barcelona, HAR2017-82755-P).

Bibliography

- “La Bienal del Tercer Mundo. Entrevista a Pierre Restany.” Arte en Colombia 43 (1990): 56–58.

- “Le muse inquiete. La Biennale di Venezia di fronte alla storia” (Padiglione Centrale, Giardini della Biennale, August 29–December 8 2020).

- 4a. Bienal de Arte Medellín Colombia. Medellin: Corporación Bienal de Arte de Medellín, 1982.

- Acha, Juan. “Tradición y contemporaneidad en el ambiente del Tercer Mundo.” In Debate Abierto Tradición y Contemporaneidad en el Ambiente del Tercer Mundo, 3–16. Havana: Centro de Arte Wifredo Lam, 1989.

- Alemani, Cecilia. “Introduzione / Introduction.” In Le muse inquiete. La Biennale di Venezia di fronte alla storia / The Disquieted Muses. When La Biennale di Venezia meets history, 25–27. Venice: La Biennale di Venezia, 2020.

- Altshuler, Bruce. Biennials and Beyond. Exhibitions that Made Art History, 1962–2022. London and New York: Phaidon, 2013.

- Altshuler, Bruce. Salon to Biennial. Exhibitions that Made Art History, 1863–1959. London and New York: Phaidon, 2008.

- Archivi e Mostre. Atti del Secondo Convegno Internazionale Archivi e Mostre / Archives and Exhibitions. Proceedings of the Second International Conference Archives and Exhibition. Venice: La Biennale di Venezia, 2014.

- Barreiro López, Paula. “Art History and the Global Challenge: A Critical Perspective.” Artl@s Bulletin 6, no. 1 (2017): 48–57.

- Barreiro López, Paula, ed. Atlántico Frío. Historias transnacional del arte y la política en los tiempos del telón de acero. Madrid: Brumaria, 2018.

- Belting, Hans, Jakob Birken and Andrea Buddensieg. The Global Contemporary and the Rise of New Art Worlds. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2013.

- Collicelli Cagol, Stefano and Vittoria Martini. “The Venice Biennale at its Turning Point.” In Making Art History in Europe After 1945 edited by Noemi del Haro García, Patricia Mayayo, and Jesus Carrillo, 83–100. New York: Routledge, 2020.

- Conselho de Arte e Cultura. “I Bienal Latino-Americana. Um evento histórico.” In I Bienal Latino Americana de S. Paulo, 20–22. São Paulo: Ministério das Relaçoes Exteriores, Ministério da Educaçao e Cultura—Funarte, Secretarua de Cultura, Ciencia e Tecnologia SP, Secretaria Municipal de Cultura—PMSP, 1978.

- DaCosta Kaufmann, Thomas, Chaterine Dossin, and Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel. “Introduction: Reintroducing circulations: Historiography and the Project of Global Art History.” In Circulation in the Global History of Art edited by Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann, Chaterine Dossin, and Béatrice Joyeux-Prune, 1–22. London/New York: Routeldge, 2015.

- Die 5. Biennale von Havana: Kunst, Gesellshcaft, Reflexion: eine Auswahl. Aachen: Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst, 1994.

- Espagne, Michel. “La notion de transfert culturel.” Revue Sciences/Lettres 1 (2013): 1–9.

- Ferguson, Bruce W. “Exhibition Rhetorics: material speech and utter sense.” In Thinking about Exhibitions edited by Reesa Greenberg, Bruce W. Ferguson, Sandy Nairne, 126–136. London/New York: Routledge, 1996.

- Fernández López, Olga. “Comisariado y exposiciones: perspectivas historiográficas.” Exit Book: revista de libros de arte y cultura visual 17 (2012): 52–69.

- Fernández López, Olga. Exposiciones y comisariado. Relatos cruzados. Madrid: Ediciones Cátedra, 2020.

- Gil Virava, Thiago. “Seis décadas da Fundação Bienal de São Paulo: um percurso arriscado.” In Bienal de São Paulo desde 1951 edited by Paulo Miyada, 365–379. São Paulo: Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, 2022.

- Greenberg, Resa, Bruce W. Ferguson, and Sandy Nairne (eds.). Thinking about Exhibitions. London and New York: Routledge, 1996.

- Greenberg, Resa. “‘Remembering Exhibitions’: From Point to Line to Web.” Tate Papers 12 (2009).

- Hernández Velázquez, Yaiza. “Who Needs ‘Exhibition Studies’?” in Critical Museology: Selected Themes Reflections from the William Bullock Lecture Series, 286-302. Mexico City: MUAC—UNAM, 2019.

- I Bienal Latino-americana de São Paulo. 40 años depois. São Paulo: Centro Cultural de São Paulo, 2019.

- Imizcoz, Catalina L. “Extending the Study of Exhibitions across Geographies.” Caiana 1, no. 10 (2017): 80–95.

- Joyeux-Prunel, Béatrice. “ARTL@S: A Spatial and Trans-national Art History Origins and Positions of a Research Program.” Artl@s Bullettin 1, no. 1 (2012): 9–25.

- Joyeux-Prunel, Béatrice. “Introduction: Do Maps Lie?” Artl@s Bulletin 2, no. 2 (2013): 4–6.

- Joyeux-Prunel, Béatrice.“ARTL@S: A Spatial and Trans-national Art History Origins and Positions of a Research Program.” Artl@s Bullettin 1, no. 1 (2012): 9–25.

- Juneja, Monica. “Global Art History and the ‘Burden of Representation’.” In Global Studies: Mapping Contemporary Art and Culture edited by Hans Belting, Jakob Birken and Andrea Buddensieg, 274–297. Ostfildern: Hatje Canitz Verlag, 2011.

- Kienle, Miriam. “Between Nodes and Edges: Possibilities and Limits of Network Analysis in Art History.” Artl@s Bulletin 6, no. 3 (2017): 4–22

- Klonk, Charlotte. Spaces of Experiencie. Art Gallery Interiors from 1800 to 2000. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009.

- Kolb, Ronald and Shwetal A. Patel. “Survey review and consideration.” OnCurating 39 (2018): 15–34.

- Lagnado, Lisette (ed.). Cultural Anthropophagy. The 24^th^ Bienal de São Paulo 1998. London, Afterall Books, 2015.

- Lauer, Mirko. “Notas sobre plástica, identidad y pobreza en el Tercer Mundo.” In Debate Abierto. Tradición y Contemporaneidad en la Plástica del Tercer Mundo, 19–27. Havana: Centro de Arte Wifredo Lam, 1989.

- Lida, Cecilia. “Entrevista a Lilian Llanes: memoria y resistencia en los inicios de la Bienal de La Habana.” Ramona 95 (2009): 11–15.

- Llanes, Llilian. “Presentación.” Tercera Bienal de la Habana ’89. CATALOGO, 13–18. Havana: Editorial Letras Cubanas, 1989.

- Llanes, Llilian. Memorias. Bienales de La Habana, 1984–1999. Havana: ArteCubano Ediciones, 2012.

- López, Miguel A. Robar la historia. Contrarrelatos y prácticas artísticas de oposición. Santiago de Chile: Metales Pesados, 2017.

- Morais, Frederico. “Apêndice: I Bienal Latino-Americana de São Paulo.” In Artes plásticas na América Latina: do transe ao transitório, 62–65. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1979.

- Niemowjeski, Rafal. “Venice or Havana: A Polemic on the Genesis of the Contemporary Biennial.” In The Biennial Reader edited by Elena Filipovic, Marieke Van Hal, and Solveig Øvstebø, 88–103. Ostfildern/Bergen: HatjeCantz Verlag/Bergen Kunsthall, 2010.

- O’ Neil, Paul. The Culture of Curating and the Curating of Culture(s). Cambridge: MIT Press, 2012.

- Ramírez González, Ilda. Debates críticos en los umbrales del arte contemporáneo. El arte de los años setenta y la fundación del Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín. Medellin: Fondo Editorial Universidad EAFIT, 2012.

- Restany, Pierre. “Bienal de La Habana. Cuba, sí Cuba, no Cuba Libre,” Cimaise 187 (1987): 2–4.

- Restany, Pierre. “Biennales.” In L’avant-garde au XXème siècle edited by Pierre Cabanne and Pierre Restany, 110–119. Paris: André Balland, 1969.

- Restany, Pierre. “Consideraciones generales sobre el arte y el Tercer Mundo.” In Debate Abierto. Tradición y Contemporaneidad en la Plástica del Tercer Mundo, 44–46. Havana: Centro de Arte Wifredo Lam, 1989.

- Restany, Pierre. “VIIIème Biennale de São Paulo: comment va la cousine australe de Venise?” Domus 432 (1965): 47–52.

- Seng, Yu Jin. “Restaging Critical Exhibitions: The will to arcive/memorialise/subjectivity.” World Art 10, nos. 2–3 (2020): 215–237.

- Sontang, Susan. Sobre la fotografía. México D.F.: Santillana Ediciones Generales, 2006.

- Staniszewski, Mary Anne. The Power of Display: A History of Exhibition Installations at the Museum of Modern Art. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1998.

- Tejeda, Isabel. El montaje expositivo como traducción. Madrid: Trama Editorial, 2015.

- Tercera Bienal de la Habana ’89. Catalogo general. Havana: Centro de Arte Wifredo Lam/Editorial Letras Cubana, 1989.

- Weiss, Rachel (ed.). Making Art Global (Part 1). The Third Havana Biennial 1989. London, Afterall Books, 2011.

- Werner, Michel and Bénédicte Zimmermann. “Penser l’histoire croisée : entre empirie et réflexivité.” Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales 1 (2013): 7–36.

Selected Bibliography

Centro Wifredo Lam, CWL

- “1 Bienal de La Habana 84”, Granma, Havana, May 28,1984 (CWL, I Bienal 1984).

- “Bienal de Havana já em preparação”, Domingo, Maputo, April 6, 1986 (CWL, II Bienal, 1986).

- “Malangatana no jurí da Bienal de Cuba”, Domingo, Maputo, May 4, 1986 (CWL, II Bienal, 1986).

- “RPM participa,” Noticias, Maputo, May 5, 1986 (CWL, II Bienal, 1986).

- Leirner, Sheila. “Havana, Bienal distante da abertura.” O Estado de Sao Paulo, June 3, 1984 (I Bienal 1984)

- Piñera, Toni. “Panorama de las artes plásticas latinoamericanas.” Granma, Havana, June 17, 1984 (CWL, I Bienal 1984)

- Joppolo, Giovanni and Lasalle Hélène. “Premiere Esquisse d’un recentrement de la diaspora africaine.” Opus International, no. 194 (1987): 14-17 (CWL, II Bienal, 1986)

- Pradel, Jean-Louis. “Quand le Paris latino-américain se déplace à La Havane” L’evenement du jeudi, Paris, February 12-18, 1987, 86 (CWL, II Bienal, 1986).

- Margarita Sánchez Prieto, Margarita. “III Bienal de La Habana. Tradición y contemporaneidad en el arte del Tercer Mundo.” La Bohemia, October 27, 1989 (CWL, III Bienal, 1989)

Arquivo Histórico Wanda Svevo - Fundação Bienal São Paulo, AHWS – FBSP

- “A arte cubana na Bienal.” Jornal da Tarde, 17 September 1985 (Caixa 53).

- “Cuba retornando à Bienal, após 22 anos de ausência.” Diário Popular, September 5, 1985 (Caixa 53).

- “Cuba volta, com Lam, à Bienal.” Jornal do Brasil, 26 March 1985 (Caixa 53).

- “Participará Cuba en la 18va. Bienal de São Paulo.” Granma, August 9, 1985 (Caixa 53).

- “Restany: Brasília, Bienal e Vanguarda” [Entrevista], Correio da manhã, September 25, 1965 (Caixa 28 – 031).

- Letter from Llilian Llanes (Director, Wifredo Lam centre) to Roberto Muylaert (President, São Paulo Biennial Foundation), Havana, August 19, 1985 (01-07997).

- Letter from Luiz Norberto Collazzi Laureiro (Executive General Secretary, São Paulo Biennial Foundation) to José - Olimpo Rache de Almeida (Head of the Department of Cooperation and Culture, Ministry of Foreign Affairs), São Paulo, October 18, 1985 (01-07536).

- Telegram from Lupe Velis (International Relations, Ministry of Culture of Cuba) to Luis Villares (São Paulo Biennial Foundation), Date Received, February 23, 1984 (01-07738).

- Telegram from Nina Hokka (Executive Secretary of the Presidency, São Paulo Biennial Foundation) to Lupe Velis (International Relations, Ministry of Culture of Cuba) and Marcia Leiseca (President, Organising Committee 1 Havana Biennial), São Paulo, February 28, 1984 (01-07738).

Institut national d’histoire de l’art-Collection Archives de la critique d'art, Rennes, INHA - ACA

- Letter from Llilian Llanes to Pierre Restany, Havana, July 11, 1997 (FR ACA PREST TOP AML 031, Fonds Pierre Restany. INHA-Collection Archives de la critique d’art, Rennes.)

- Palabras del señor Juan Acha, Director del Primer Coloquio Latino-Americano sobre arte no-objetual, en la sesión de instalación del evento (FR ACA PREST.XSAML03, Fonds Pierre Restany. INHA-Collection Archives de la critique d’art, Rennes.)

- Letter from Pierre Restany to Llilian Llanes, Paris, August 31, 1996 (FR ACA PREST TOP AML 031, Fonds Pierre Restany. INHA-Collection Archives de la critique d’art, Rennes.)

- Pierre Restany, “São Paulo 1965: Calme Plat” (FR ACA PREST.XSAML 17, Fonds Pierre Restany. INHA-Collection Archives de la critique d’art, Rennes.)

Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros – Universidade de São Paulo, IEB – USP

- Amaral, Aracy. “Bienal de Havana, um balanço positivo.” Folha de S.Paulo, June 12, 1984 (AAA-AA-119)

Musée d’Art moderne de Paris – Archives de Pierre Gaudibert (MAM-ARC-APG)

- Gaudibert, Pierre. “Por un métissage culturel.” Le monde diplomatique, Paris, February, 1990 (MAM-ARCH-APG-EC)

- Gaudibert, Pierre. “Por un mestizaje cultural.” Granma, Havana, April 29, 1990 (MAM-ARCH-APG-EC).