Earle’s Lithography and the Force of Law

Augustus Earle is regularly credited as the most widely travelled independent, professionally trained artist in the first half of the nineteenth century. He was, as Jocelyn Hackforth-Jones claims, probably the first “freelance travel artist to tour the world.”1 Bernard Smith, evoking a similar sense of new-found freedom, suggests that during “a period of approximately twenty years he [Earle] wandered about the world perhaps more extensively than any [other] artist before him.”2 As part of this ceaseless drifting across the globe, Earle, more by accident than by design, found himself in Australia. He arrived in Hobart in January 1825 and went on to Sydney later that year where he stayed—except for a six-month visit to New Zealand—until October 1828. As Earle’s time in Australia was relatively brief, and given the constant discussion of his peripatetic nature, it might be presumed that Australia was no more than of passing interest to him. Yet, I will approach Earle differently, arguing that his substantial investment in establishing not only a possible home for himself in Australia, but equally for art, should not be overlooked.

During his stay in Sydney, Earle opened Australia’s first art gallery, displaying selected prints of “great works” from across the history of European art.3 He also taught art classes at the gallery, in what may have been Australia’s first art school.4 However, as an indicator of his long-term ambitions, the gallery was also more importantly the location of his lithographic printing business, Earle’s Lithography, the eponym with which he signed his prints. Earle acquired his lithographic press from the then Governor of New South Wales, Sir Thomas Brisbane, who originally had the press shipped to Sydney in order to publish his astronomical observations. In contrast, Earle saw lithography’s artistic, rather than solely scientific, potential. In November 1826, he published two lithographic prints, the first in what was planned to be a series of ongoing monthly publications under the collective title, Views in Australia.5 This article will analyse one of these two inaugural prints, View from the Sydney Hotel (fig. 1). As part of the first edition of his projected artistic venture, it is no surprise that this print could be read allegorically as representing the establishing of art in Australia. What may not be so evident, however, is the role that the figure of the law plays in Earle’s foundational image.

In the right-hand foreground of the image stand two figures. One faces away from the viewer. He is a distinguished civilian, with his attire indicating he is a member of the legal profession. As we cannot see his face, and thus is depicted without the distinguishing traits of a personal identity, he is included in the image more as a representative of the law. In conversation with “the law” is another representative figure, a high-ranking military man, judging from the attachment of the large feather plume. In the interaction that Earle depicts between these two representative figures, why does the law turn its back to the lone Aboriginal man? Is Earle showing us that in colonial Australia the law turns a blind eye to the fate of Aboriginal people? Undoubtedly yes, but a close analysis of the image reveals that Earle has even more to tell us about the nature of law in Australian colonial society. Drawing upon Giorgio Agamben’s thesis that the ontological status of law is determined by what occurs in the supposedly excluded state of its suspension, it will be proposed that Earle’s image demonstrates how the emergence of art in Australia is inseparable from questions of law. With Earle, the violent inscription of what Agamben, after Derrida, refers to as the force of law is one with the mark of the artist.

The New Economy of the Image

Earle advertised his new lithographic enterprise with an announcement in the local press that his artistic talents were available to produce “circulars” on “any subject whatsoever.”6 This thematic of the economic circulation of the image—the circular—is reflected in the subject matter of View from the Sydney Hotel. As one horse-drawn cart is about to exit the town, another has already replaced it, hastily making its way towards the harbour port below. If one also notices how Earle has drawn attention to the tracks carved into the street, then this is no isolated journey into and out of town, but a continual, repeated loop. The carts, as transporters of goods, establish a connection with the port below, the site for the ever-escalating transaction of commodities. In this sense, the image addresses the notion of commercial potential.

In his reflections on life in early colonial Sydney, the eminent lawyer and judge, James Sheen Dowling, comments on the changing character of George Street, the setting of Earle’s print. Dowling writes:

George Street:—the main artery through which the vital stream of commerce flows to the remotest parts of the Colony, extends in an unbroken line from Dawes’ Point, the northern extremity of the City, to the old Toll Bar, at the southern, a distance of two miles, and is continued nearly another mile under the name of Parramatta Street, connecting the extensive and populous suburbs of Chippendale and Redfern with the City, and forming the grand approach from the southern and western districts. The newcomer cannot fail of being surprised with the bustle and animation that pervades this street … 7

Although Dowling is describing what George Street had become sometime after Earle made the print, arguably, this is the future towards which Earle’s work, or let us say the horse and cart that is about to exit out of frame, is directed. As a print which is doubling as an image of the founding of a new colony and Earle’s new business project, Earle would doubtless be wishing to associate the future economic prospects of the colony with his own printing enterprise. Thus, if Dowling metaphorically speaks of George Street as the main artery through which the colony’s vital stream of commerce flows, then Earle’s aim would surely be to include his own prints among the various commodities transported along this thoroughfare. Further, if the circular path of the carts highlighted in Earle’s print can be understood as a figure for the circulation of all the various products in this thriving new colony, then it also stands for one in particular, this print—this image. The grooves of the tracks of the carts as they repeat their endless cycle (the circulation of capital) would equally then be a doubling of the trace of the “inscription” (lithography as a form of “writing in stone”) that forms Earle’s own print.

Within this everyday colonial scene of economic circulation and exchange, Earle has been quite particular with his placement of the equally representative figure of the “Aborigine.” Although in a prominent foreground position, he is unable to occupy a position on the street, or even on the footpath, as many of the other colonials seem to be able to with such calm self-assurance. Where, therefore, does he stand in relation to this new economy of the image? Or more specifically, what is the relation between the inscriptions of the artist, the instituting of art in Australia, and the representative figure of the Aborigine?

Speed and Distraction

To begin to approach the significance of the inscriptions that have left their mark on the road, the repetitive movement of the carts themselves should first be considered. As noted above, a horse and cart has passed the Aboriginal man on its way into town and another is about to pass him travelling from the opposite direction. This seemingly straightforward observation is not, however, entirely accurate. While the exiting cart has yet to pass the Aboriginal man, Earle has created an effect whereby it is as though the cart already has. An examination of the staff held by the Aboriginal man helps to clarify this view. By following the line of the staff backwards into the image, it becomes apparent that Earle has carefully positioned the wheels of the cart to be just ahead of this line (fig. 2). If this line is extended even further backwards, it meets the base of the cream-coloured wall on the opposite side of the street, roughly at the point where the wall begins and in line with the edge of the paved footpath. The V-shape created by these lines direct the eye backwards into the picture, but also forwards out of the picture. This adds to the sense of movement in the image and the speed of the exiting cart. By rendering the horse’s front left leg lifted high, the reins pulled tight, and the horse reaching forward, it is clear that Earle wished to convey that the horse is at full trot, charging as fast as possible into the future. This sense of speed is further accentuated by the manner in which the horse is set against the smoothness of the wall in the background, which can be quickly scanned because of its immaculate finish. In a sense, this element completes the horse’s projected movement. As the viewer’s look advances in front of the horse, it is as if the horse is being positioned ahead of where it presently is, which is to say in front of the Aboriginal man. This crucial effect, once noticed, is further established by many other interrelated details in the image, adding to the complexity of the deceptively simple scene that Earle portrays.

The driver of the cart leaving town (the cart facing the viewer) is depicted with his head turned. Instead of focusing on the road ahead, the driver glances to the side, momentarily distracted. Who and what is he looking at? At first, it appears that he has turned to look at the Aboriginal man by the roadside, but his gaze is in fact directed elsewhere.8 Standing up in the cart, the suggestion is more that he is looking above this man and across to the verandah of the guardhouse where three soldiers stand. Hence there is, again, an overlooking of, or an inability to see, the Aboriginal man. This is so not only because the driver’s look is diverted as he approaches him, but also, as has been argued, insofar as the driver has also already passed him by. Thus, in the next moment, when the driver begins to turn his head back to what lies ahead, it is not to suggest that he would see the Aboriginal man in so doing. From the look to the side and then back to the front, the Aboriginal man will not be visible to the driver as he will have already been placed behind the driver—already, it could be said, relegated to the past.

Equally, this movement from the side to the front as eclipsing the visibility of the Aboriginal man could be understood in terms of the implicit connection that Earle is drawing between the cart-driver and his horse. Depicted with a noticeable lean, the horse veers to the left, away from the Aboriginal man. The horse is also wearing blinkers and is thus, like his driver, blind to the Aboriginal man. Moreover, the blinkering of the horse makes the creature single-minded and determined; it is an animal become machine—the cart already heralding the motorised vehicle—with no other possible purpose than getting into and out of town as expediently as possible. And this assists in further connecting the two carts. Unlike the cart that is exiting, the driver of the cart making his way towards the harbour port would have seen the Aboriginal man as he entered town. As counterintuitive as it might seem, however, this is not actually the case. The exiting cart, seemingly yet to overtake the Aboriginal man, is in fact the other cart that has already passed him by. The entering cart-driver that we only see from behind, who has his back to the Aboriginal man and cannot at this moment see him, effectively doubles the blinkered vision of the cart-driver leaving town. One repeats the other as each fails to see him.

The Social Bond

To reinforce this reading, the same could be said of the stiffly posed soldier on the verandah. His erect posture establishes a link with the slight oddity of the driver, since he also stands upright. However more than this, as the soldier is commencing to step forward, and as we also see him as in line with the man in the cart, he is following the same trajectory. Like an automaton, he will mechanically march forward and then turn to retrace his steps, finding himself once again at the exact position where he now presently stands. The inference therefore is that the repetition of this mindless movement back and forth is precisely like that of the carts that repeat their entering and exiting. And more to the point, this is the same repetition in the failure to see the Aboriginal man. From where he stands, the soldier is also above the level of the Aboriginal man and thus he is unable to see him. There is, furthermore, an important subtlety to the composition that might at first pass unnoticed. The soldier holds his rifle upright and in front of his face. It is not completely straight however but at a slight angle, thereby positioning it in alignment with the first right-hand pillar. If this correlation is projected forward, then the rifle, in combination with the pillar, blocks out the Aboriginal man. The result is the same blinkering of the soldier’s vision.

Earle adds even further details to enhance this point. In their order and regularity, the steps to the verandah mimic the march of the soldier. As these steps come forward, imposing themselves on the more irregular and unkept grass and dirt, it is as if they are pushing the Aboriginal man to the side. This impression is underlined by the manner in which the steps connect with the well-trodden and heavily incised path. Turning to the left, this path is in symmetrical opposition to the horse as it veers to the right. It is hence as if each is diverted in their combined ignorance of the Aboriginal man. The closed blinds at the end of the verandah also serve the same end. It is mid-morning; the sun is shining onto the verandah from the left, the East. There is thus no functional reason for the blinds to be drawn. But similar to the two cart-drivers—effectively one as they complete the same circuit, entering and exiting without seeing—so too the closed blinds figure the soldier’s lack of sight. It can be assumed that the solider is on duty—on watch—but is his purpose not actually the opposite? He will repeat his march only to ensure that he sees nothing. His vision is like the blankness of the brick wall of the guardhouse that cuts across the spectator’s view and which also, if it is proposed that the soldier turns back on reaching the steps to the verandah, marks the limit of the soldier’s forward march. As this wall so blatantly and dumbly faces the front, reiterating the dead end of the closed blinds, so it is that the solider will remain incapable of seeing what is, in fact, just before him.

As much as one might initially be drawn to this solider, as he does indeed stand out like the similarly upright and thus also over-exposed cart-driver, the other two soldiers should not be neglected. In contrast to their colleague who is clearly on duty, these two men are off duty. Perhaps they have just finished their shift and are relaxing against the verandah rail. One of the men faces away from the street and like his on-duty colleague appears unaware of his surroundings. The other soldier leans forward over the verandah rail, presumably to look out to the street. He is the only one of the three granted any visual awareness in the scene. Yet strangely, he is also the only one whose face is obscured from view, hidden behind his colleague and a pillar. Thus, even if he is able to see what is happening on the street, what or who he sees is not immediately clear. Why might have Earle, knowingly or not, done this?

The cart-driver’s sideways glance has been described above as directed towards the verandah. But a closer analysis enables us to be more precise on this point. Rather than just to the verandah, I would propose instead that the man’s eye has been caught by the one soldier we cannot see. The casualness of the soldier’s pose also intimates that there might be more than a simple exchange of glances taking place. Perhaps there was a good-humoured greeting or the acknowledgment of a shared joke. Of course, we cannot know exactly what transpired, nonetheless the evident suggestion is that there is some level of interaction, however brief and fleeting, that establishes a social bond between the two. This is not, though, without paradox and an “evident suggestion” would appear to be a contradiction in terms. Something here remains hidden, secret. Yet, according to the equations that the image is putting in place, what is unseen is nevertheless exposed in the clear light of day. The cart-driver could have turned to see the Aboriginal man, but this did not happen because his sighting of the military ensured that he did not enter into his thoughts nor field of vision. It is thus the military that has effectively removed the Aboriginal man. The humorous exchange—the social bond created out of sight behind the pillar—might at first seem to be unrelated to this erasure. What, however, is in front of the pillar and what is obscured behind it are one and the same. One is the other as the creation of any social bond in this new colony is equally at the expense, or the exclusion, of any Aboriginal presence.

The Military and the Law

Let us then finally return to the significance of the exchange between the two representative figures of the military and the law. As previously suggested, the costumes of the two men clearly establish their high social ranking. Yet, even without such sartorial indicators, the fact that both men stand unperturbed in the middle of the street equally conveys a sense of authority. The crossed arms of the military and the hands of the law in his pockets can be read as a sign that these two individuals expect others to navigate around them. With their poses that evoke an aristocratic nonchalance, they equally stand there as if to calmly, but at the same time quite pointedly, assert that the public space that is the street is indeed their domain.

Absorbed in what is no doubt learned discussion, what then occupies their thoughts in such a highly visible social space? What matters of public good are they addressing? Will their attention be drawn to the Aboriginal man in the foreground and will his plight enter into their seriously weighted discussion? It would seem not. The military man has his body facing in the opposite direction to the lawyer. However, even if from this position it might be possible for him to see the Aboriginal man, the manner in which he is turned towards the law, in a look that cuts across the picture plane and that runs in line with his own projected shadow, pronounces his obliviousness to this Aboriginal man. Though it is perhaps necessary to qualify this. If not oblivious exactly, he is at least knowingly oblivious, as it is possible to imagine that he could well be keeping the lawyer in conversation precisely so that the Aboriginal man will remain unseen and unconsidered, outside of the purview of the law. In both cases, however, as if to emphasise that the military will maintain its ignorance, even if it is feigned, it is not simply Earle’s addition of the line of the shadow which should be noted, with the military as a consequence placing the law in the dark, it is also, if one looks closely at the military figure’s face, that he appears to be wearing glasses, a pair of pince-nez. Like the blinkers on the horse, these glasses are darkened, thereby figuring his own turning away from the Aboriginal man. This repeated play upon blindness is ultimately registered by how the law rather blatantly faces away from the spectator and also, of course, the Aboriginal man. Thus, these two will not converse on him. In this colony, with regard to any Aboriginal concerns, law turns a blind eye.

This figurative blindness, however, should not be where the analysis ends, as there is much more than this common, everyday expression that Earle allows us to see. The exacting subtlety characteristic of Earle’s art begins to emerge if we adjust our perception about whether the two figures—the law and the military—are standing in “the middle of the street.” The two are in reality not in the middle of the street; they are placed slightly off-centre. But the significance of this positioning is that it shifts them more into the centre of what I referred to earlier as the V-shaped area that is created by the diagonal of the Aboriginal man’s staff and the line of the wall running along the opposite side of the street. If this represents a space that can be interpreted as dramatising the colony’s expansion—with the cart speedily exiting to exploit new territory—then, with his staff becoming a barrier, it is an area from which the Aboriginal man is excluded. As much as he might attempt to use his staff as a means of support, enabling him to lift himself up so that he could fully emerge and stand on flat, secure land, this is repeatedly undermined by the violent incisions that circle around him. None of this violence however seems to be the concern of the law. The law looks elsewhere. Yet, like the face of the soldier that we cannot see behind the pillar, it is not that this hidden side—the violence—is the complete reverse of what we can see. In terms of the law, this is to say that the force of the inscriptions which surround the Aboriginal man are not to be thought of as necessarily opposed to the way in which the law institutes itself. Whether this be Earle’s intention or not, insofar as what is behind the law’s back is inverted to be positioned in the front, that is, to be in the visible foreground of the image we see, he is showing us that it is what the law does not see that is the law. This, indeed, is why Earle’s image is a foundational view of Australia.

The Relation of Exception

To justify this claim I wish to turn to a more theoretical and speculative line of argument, one that points to the wider implications beyond this one example of Earle’s work that I have considered here. The inversion that occurs in View from the Sydney Hotel can be understood as exemplifying Giorgio Agamben’s thesis that modernity begins with the paradoxical situation whereby the exception to the law (the state of emergency), or in the case of Australia the martial law that was repeatedly declared across the country, actually establishes the law.9 The suspending or violating of the law as constituting the law is what Agamben refers to as a “relation of exception,” and he considers this to be the “original formal structure of the juridical relation.”10 As he explains, in the relation between the exception to the law and the rule of law:

The exception does not subtract itself from the rule; rather, the rule, suspending itself, gives rise to the exception and, maintaining itself in relation to the exception, first constitutes itself as rule. The particular “force” of law consists in this capacity of law to maintain itself in relation to an exteriority. We shall give the name relation of exception to the extreme form of relation by which something is included solely through its exclusion.11

Earle images this extreme form of relation. Everything circulates in the new colony around the figure of the Aborigine as this something which “is included solely through its exclusion.” The particular force of law in the work could consequently also be seen as the intensity of the lines—the incisions in the road that double as lithographic engravings—that aggressively turn around the Aboriginal man. These inscriptions of the force of law would also then be registering the capacity of the law “to maintain itself in relation to an exteriority.”

For the law, however, to maintain itself in relation to an exteriority with these inscriptions, an important implication is that these jagged lines would not just be the force of law as that which severs the Aboriginal man from his land. As Agamben further argues, providing a commentary on the political theory of Carl Schmitt: “The ‘ordering of space’ that is, according to Schmitt, constitutive of the sovereign nomos is therefore not only a ‘taking of land’ … but above all a ‘taking of the outside.’ an exception.”12 Earle’s foundational view of Australia can thus be read as this primary “ordering of space,” one in which there is both a “taking of land” and a “taking of the outside.” Although it might initially appear as if the Aboriginal man is turning so as to step out of some deep recess, some non-descript hole in the ground, this is not the case. With his staff not in contact with the ground, or as this equally could be thought, not connecting with the material support of the image, he is not seeking assistance so as to raise himself out of a hollow, some absence or vacancy that could be included in space. Rather, with the paradoxical contact-less touch of his staff, the Aboriginal man is embodying a void, an impossible non-place.13 The inscriptions that viciously swerve around him do not only therefore enforce a “taking of land,” but also a “taking of the outside.”

The Afterglow

My reading of Earle’s image after Agamben is not that the law has simply turned away from the violence. Law becomes law, or more emphatically, law is law, only in the turning away. This is not to say, however, that what can be seen behind law’s back in Earle’s image will not be repeatedly erased by the history of Australian art. As another speculative suggestion of what follows from the study of this one image, I can add a final observation. Although we have said that the law is in conversation with the military, the law is not directly facing the military. While the law might be in discussion with the military, Earle has positioned the figure of the law such that he looks past the military. All the law sees is a smoothly rendered blank wall. Turning away, not seeing the Aboriginal man, the emptiness of this wall can be understood to be the immediate profitable outcome that results from this. The cart-driver as colonial landowner will speed by this wall with no time to waste, as the prospect of endless commerce and the exploitation of a yet further empty expanse lies ahead. Equally, if it is, as was suggested, Earle’s own print that is one of the potential commodities that is placed into circulation on this street, then the blank canvas of this wall, or better perhaps, this freshly prepared lithographic surface, is ready to receive “any subject whatsoever.”

The potentiality of this surface is not, however, presented in isolation. Inordinate attention is given to another, even more expansive (and more immaculate) surface behind: the vast side wall of the building that extends back towards the harbour. That this building covers a sizable area of what is presented as the mountain range in the background—which, in actuality, if you were to view the scene today is just mere hills—adds to the imposing breadth and depth of this building. However, and this the figure of the law cannot see, so it thus joins with what is behind him, the ultimate pure surface in front of the law is the harbour. No violence disturbs the harbour’s surface, there is not even a trace of a ripple. A ship peacefully rests there, finding itself almost magically reflected in the water. Although out in the water, this boat is fully enclosed—the walls and roofs of the buildings along the street, in tandem with the land on the other side of the harbour, contain it, safely frame it. In contrast to the Aboriginal man in the foreground of the image, the ship’s inclusion in the ordering of colonial space is affirmed, with any open area, any borders, reassuringly sealed. Doubtless to be read as a repetition of the founding of the colony, of the first British ship to enter the harbour, this is a repetition that represses law’s origin.

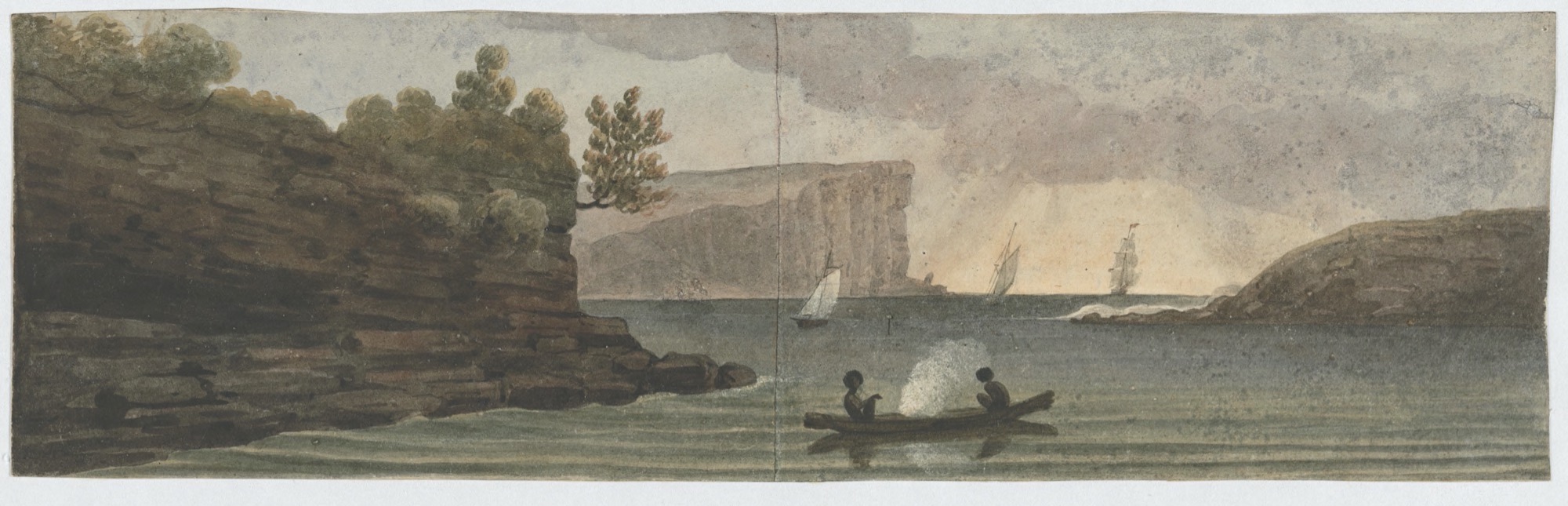

Bernard Smith believed that in the background of one of Earle’s watercolours he could detect the future direction of Australian art. Of Port Jackson (fig. 9) he wrote, there was, ‘perhaps, the earliest attempt to portray the suffused rose and mauve tones of an afterglow over Sydney Harbour during a summer or early autumn evening—an effect greatly favoured by the Australian plein air and impressionist painters of the last two decades of the [nineteenth] century.’14 Although a seemingly innocent aesthetic effect, if one views another Port Jackson watercolour by Earle, a significance beyond that of the purely atmospheric is attached to the “afterglow” (fig. 10). In noting the presence of Aboriginal people in the foreground of one and not the other, the setting of the sun can be associated with the melancholic passing of the Aboriginal people. The “effect” that the Australian impressionist painters so desired, the delicate abstraction of their painterly gestures that would evoke the “afterglow,” could then be understood as a further sublimation, or a forgetting, of what Earle so emphatically included in the foreground of so many of his works.15 If we return for the final time to the foundational image of View from the Sydney Hotel, then this would further imply that after Earle, Australian art consists of the transitioning away from one side of the law to the other, or more, as an attempt to dissociate art and law, as if there were indeed two sides to the law. Yet, if this so, then, as this article has attempted to demonstrate, Earle’s work persists as a salutary reminder that this dissociation is not the case, requiring us to turn and look again at what has been placed behind our backs, re-assessing as we do so our understanding of what law is.

-

Jocelyn Hackforth-Jones, Augustus Earle, Travel Artist: Paintings and Drawings in the Rex Nan Kivell Collection, National Library of Australia (Canberra: National Library of Australia, 1980), 1. ↩

-

Bernard Smith, European Vision and the South Pacific 1768–1850 (London: Oxford University Press, 1960), 190. ↩

-

In the advertisement for the gallery Earle makes note of how original prints by Van Dyck, Carracci, Rosa, and Rembrandt would be for sale. Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, December 27, 1826. ↩

-

He placed a call for pupils under the title of “School of Painting” in The Monitor, August 25, 1826. ↩

-

The first review of these two prints appeared in The Monitor, November 3, 1826. ↩

-

The Monitor, November 3, 1826. ↩

-

James Sheen Dowling, Reminiscences of a Colonial Judge (Leichardt: Federation Press, 1996), 23. ↩

-

The look to the side is a key structural device that Earle used consistently. The most relevant example is in Earle’s major painting, Waterfall in Australia (1830). This work includes a self-portrait of Earle. Although many have assumed that Earle has turned to the side to look at an Aboriginal man standing in front of a waterfall, Leonard Bell argues that he is in fact looking past this man, and thus misses seeing him. In the earlier View from the Sydney Hotel, Earle depicts the same scenario. There are many fascinating parallels between the two works as it can be argued that the driver of the cart in this earlier print is also a self-portrait, or at least a stand in, for Earle. Leonard Bell, “Colonial Eyes Transformed: Looking at/in Paintings: An Exploratory Essay,” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art 1, no. 1 (2000): 42–64. ↩

-

Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998) and State of Exception, trans. Kevin Attell (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2005). These are Agamben’s two main works on this topic. For Agamben’s discussion of martial law specifically, see State of Exception, 18. ↩

-

Agamben, Homo Sacer, 19. ↩

-

Agamben, 18. ↩

-

Agamben, 18. ↩

-

I have argued that there is the same relation between staff and void in Earle’s Waterfall in Australia. See Keith Broadfoot, “Augustus Earle’s Waterfall in Australia and the Logic of Fantasy,” Art History 42, no. 5 (2019): 914-935. ↩

-

Smith, European Vision and the South Pacific, 193. ↩

-

For more on the melancholy effect of Australian impressionism as a sublimation of colonial violence, see Chapter 4, “The Bad Conscience of Impressionism,” in Ian McLean, White Aborigines: Identity Politics in Australian Art (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 52–73. ↩

Keith Broadfoot is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Art History at the University of Sydney, Australia. His recent publications have appeared in Art History, Angelaki, and the Journal of Art Historiography.

Bibliography

- Agamben, Giorgio. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Translated by Daniel Heller-Roazen. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998.

- Agamben, Giorgio. State of Exception. Translated by Kevin Attell. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- Bell, Leonard. “Colonial Eyes Transformed: Looking at/in Paintings: An Exploratory Essay.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art 1, no. 1 (2000): 42–64.

- Dowling, James Sheen. Reminiscences of a Colonial Judge. Leichardt: Federation Press, 1996.

- Hackforth-Jones, Jocelyn. Augustus Earle, Travel Artist: Paintings and Drawings in the Rex Nan Kivell Collection, National Library of Australia. Canberra: National Library of Australia, 1980.

- McLean, Ian. White Aborigines: Identity Politics in Australian Art. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- The Monitor. Sydney: 1826–1828. National Library of Australia. Accessed August 28, 2020. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-title3.

- Smith, Bernard. European Vision and the South Pacific 1778–1850. London: Oxford University Press, 1960.

- Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. Sydney: G. Howe, 1803–1842. National Library of Australia. Accessed August 28, 2020. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-title3.