Digging for Honey Ants Revisiting the Papunya Mural Project

Strange how things in the offing, once they’re sensed,

Convert to the foreknown;

And how what’s come upon is manifest

Seamus Heaney, 19911

The creation of the Honey Ant Mural at Papunya in 1971 is now recognised as a “defining moment” in the development of Australian Art. This essay began to take form when writing the second in a sequence of lectures for the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art.2 The series, Defining Moments: Australian Exhibition Histories 1968–1999 was conceived by the centre’s Artistic Director, Max Delaney, who challenged presenters to “take a deeper look at the moments that have shaped Australian art since 1968.” Delaney selected subjects that he considered to be: “Ambitious, contested, polemical, genre-defining and genre-defying, contemporary art exhibitions [that] have shaped and transformed the cultural landscape, along with our understanding of what constitutes art itself.”3 Although not strictly an exhibition, the Honey Ant Mural fits the criteria.

Sandwiched between John Kaldor’s recollections of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Wrapped Coast, 1968–1969, and Julie Ewington’s analysis of the Mildura Sculpture Triennial, 1973, 1975 and 1978, I spoke about the production of one in a sequence of murals painted on walls within a primary school, at a remote Indigenous community in Central Australia, by a then unknown group of school yardmen and their peers. Although it is now regarded with gravitas, at the time the Honey Ant Mural was barely noticed outside Papunya. Just three years after their creation, the Northern Territory Education Department engaged contractors to repaint the school, whitewashing the murals.4 As a consequence, very few people, other than expatriate schoolteachers, students and their parents, saw the now famous Honey Ant Mural. The mural’s existence was largely overlooked until 1986, when the first image of a semi-abstract icon, filling a long wall, under a veranda at the Papunya School, was reproduced in Dot and Circle: a retrospective survey of the Aboriginal acrylic paintings of Central Australia.5 The legendary status of the Honey Ant Mural has grown steadily ever since.6

This essay will relocate the mural in place and time, while scrutinising the roles of the key players associated with its origin. Further, it will discuss how a mural, so long overlooked, has now attained near mythological status. Most importantly, the essay seeks to balance the mural’s significance with other influential expressions of Indigenous culture that emerged in Central Australia during the 1970s. It is only then that the mural’s significance can be weighed against other events that contributed to the formation of a contemporary desert art movement that has fundamentally changed the face, and trajectory of Australian art.

Place

Papunya rests on the Tropic of Capricorn, 250 kilometres west of Alice Springs in Honey Ant Country. From October each year monsoonal storms scud across the plain from the Tanami Desert. Below the ground tjala (honey ants) hang, suspended in the darkness of underground chambers.7 Unmoving, they wait to be fed by worker ants that carry exudate from the branches of mulga trees under which colonies of honeypot ants reside—living larders. The chambers of tjala are invisible from the surface, but well known to local people who follow the cryptic traces of worker ants across the earth to tiny holes that plummet a metre into the earth. From this cool place, numerous smaller tunnels are traced as they radiate to reach further chambers in which more honeypots cling, a handful in each chamber, their abdomens distended with sweet nectar.

Dick Kimber, historian and author, has noted the importance of Honey Ants to the people of Central Australia. Not only do they provide a rare source of sweetness but more significantly, their interconnected chambers exemplify important aspects of Indigenous ontology. The subterranean reality of the honey ant colonies epitomise notions of community and connectedness at the heart of Aboriginal belief. Their underground presence gives force to the concept of the earth as the original life-giver. 8

Unsurprisingly, tjala feature in the spiritual and ceremonial lives of Central Australian people, their cultural significance outweighing their size or the lowly status accorded invertebrates in European culture. In the harsh desiccated environment of Central Australia, their liquid sweetness, while hard won, signifies the bounty of the land.

PEOPLE

Papunya is located at a point at which three distinct cultural groups meet. Like Switzerland, where multilingualism is the norm, several languages are spoken at Papunya. The site, Papunya is in Kukatja country, the morpheme kuka, indicating this a dialect of the Western Desert language that also includes Pintupi, Luritja, Ngaatjatjarra and Pitjantjatjara speaking people, all of whom use the term kuka for meat.9 The Warlpiri speaking nation is centred at Yuendumu, a large community one hundred kilometres to the north. Yuendumu is also located on Honey Ant country though that site does not carry the same ritual pre-eminence as does Papunya and nearby Warumpi. Arandic languages are spoken to the east and northeast of Papunya. Significantly, for the focus of this lecture, Kaapa Tjampitjinpa and his cousin Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri were Anmatyerr men from Napperby Station to the near northeast. Both artists produced representations of Honey Ant songlines and each was critical to the establishment of the contemporary art movement at Papunya.

HISTORY

Papunya operated as a government settlement for little more than a decade before the inception of the painting movement for which it is now famous. In 1954, a bore was struck at the site from which the community gets its name. This bore was initially intended for cattle.10 Then, as potable water became scarce at neighbouring Haasts Bluff, the Welfare Branch decided to relocate most of that station’s residents to Papunya where there was an abundant flow of good water. In 1959, the architect of the assimilation policy, Paul Hasluck, opened the new settlement in his role as Minister for Territories. Some of the men, who would become muralists, were employed constructing settlement infrastructure before the minister’s visit.11 Papunya was established as a site where disparate people, from across the Central and Western Deserts, were relocated by the colonial administration to be trained in European ways.12 As late as 1966, a group of desert dwelling Pintupi people from Kurlkurta and Yawayurru in Western Australia were trucked into the rambling government settlement. Remarkably, one member of that group, Anatjari Tjakamarra would become the first Aboriginal artist whose work was collected by the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1988.13

CIRCULAR TIME

In February 2019, on a morning walk near Unyali, in the ranges to the south of Papunya, I came across a tjungari (grindstone). Too cumbersome to carry, it had been left in place for future use. The tjungari affords enduring insight into the seed-grinding technology that has sustained people in Central Australia.14 The grindstone may have been last used in the mid-twentieth century, or, perhaps it was exposed more recently, after being forsaken in previous millennia. Despite not knowing the exact age of the stone, it is likely to have been worked by women of the local Honey Ant totem. Circling through time, Papunya has been a site for the celebration of Honey Ant ancestors. The innumerable children conceived in the vicinity of Papunya are recognised as having ancestral connection to these eternal honey ant ancestors. Papunya is Honey Ant country.15

In 1955, the linguist and ethnographer T. G. H. Strehlow made a film of elaborate rituals associated with the Tjala/Honey Ant songline. Performed by Paddy Anatari and Parta (Bert) Nananana, the film now stands as the most complete record of the ceremonies associated with Papunya, the site where contemporary Aboriginal painting emerged.16 Indeed, Nananana was among the senior custodians who oversaw the production of the Honey Ant mural on the wall of the Papunya school in 1971.17 I was fortunate to have become acquainted with both Anatari and Nananana when, as a young man, I worked as art advisor to Papunya Tula Artists in the late 1970s.

Episodes that Anatari and Nananana performed over a succession of days, reach their climax at Papunya, where elaborate structures were constructed to signify the actions of the Honey Ant sire and his company. These “inside” sequences belong to the restricted realm of men’s ritual and as a consequence were not detailed on the school wall. Rather, “open” aspects of the ritual complex were inscribed.

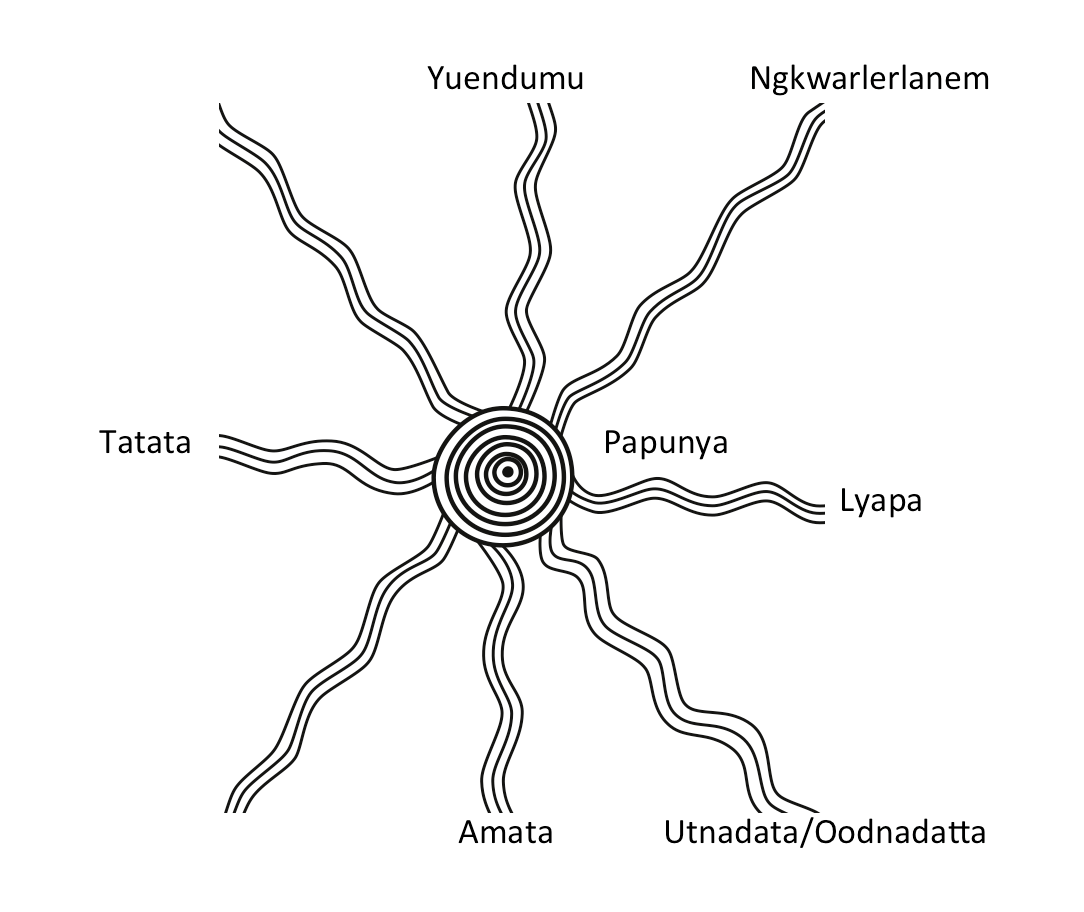

Like the hub of a great wheel, Papunya is conceived as being at the centre where Honey Ant songlines from distant lands converge—from Tatata in Pintupi country to the west; from Yuendumu in Warlpiri/Anmatyerr country in the north; from Akwerrperl (Korbula) in Anmatyerr country and Ngkwarlerlanem (‘where the honey is’) in Alyawarr country to the northeast; from Lyapa, in Northern Arrernte country to the east; even as far as Utnadata (‘the catkins on mulga trees’) in Lower Arrernte country, a site better known as Oodnadatta, in South Australia, 1000 kilometres southeast of Papunya.

CHANGING TIME

Papunya was the last of the big settlements of the assimilationist era, training camps where disparate people were translocated for the government’s convenience. New skills were to be transferred to the coming generation while the old people, such as Nananana, were expected to spend their remaining years passively, as pensioners. Initially, during the construction phase, the settlement provided employment, opportunities that were taken up by men such as Kaapa and Tim Leura who had previously worked as stockman on the neighbouring cattle stations.18

Cracks had already emerged in the mantle of the assimilation policy when Geoffrey Bardon arrived as a teacher at the Papunya Special School in 1971. People chose not to adopt the ways of the colonisers; literacy levels were low, while morbidity and mortality, especially among the very young and elderly, remained shockingly high. Moreover, the community itself was riven with conflict. Riots flared at regular intervals as subjugated residents, outraged by their treatment by European staff, expressed their anger.19 Conflict also occurred between clans, who according to the strength of their associations with the site, could claim greater, or lesser agency among a swelling population, all of whom endured crushing poverty.20 The Eastern Pintupi for instance could rightfully call on a connection to Papunya via the Honey Ant songline from Tatata. In contrast, the western Pintupi had no such claim. They were regarded as ‘myall’ (being unaware of the modern ways), by those raised on missions and cattle stations who had a longer experience of non-Indigenous people.21 The western Pintupi lived at the ‘Piggery Camp’ on the west side of town, a long walk from reticulated water but oriented towards their home country.22 The meaning and intent of the Honey Ant mural must therefore be interpreted with regard to the complex cultural topography of Papunya, as well as through the lens of settler/Indigenous relations in the mid-twentieth century.

THE PROTAGONISTS

Like many of the new breed of southern whitefellas who would follow in his wake, Geoffrey Bardon had little sympathy for the assimilation policy and its aims.23 This cohort, of whom I am one, was fascinated by Aboriginal culture. We naïvely sought ways to recognize and bolster customary practice.24 Unwilling to identify with the colonial regime of which he was a part, Bardon’s obdurate disregard of settlement authorities brought him into direct conflict with those on whom he would rely for the resources to see through his ambitious plans. Bardon’s stay at Papunya was short, drama-filled but undeniably influential.25

Kaapa, on the other hand, was a pragmatist who would take advantage of any regime he encountered. Curious and intelligent, Kaapa prised open cracks in the colonial façade to expose new opportunities for himself and his family. Unwilling to express allegiance to any stamp of the European governance, Kaapa exploited the colonial infrastructure. He moved with confidence between a studio he established in an abandoned government office, and the school where he could access good quality brushes, paints and even discarded blackboards that he requisitioned as a substrate on which to paint his revolutionary representation of ceremony. His images were calculated to appeal to an interested non-Indigenous audience of schoolteachers and government officials.26

Kaapa’s most important education came under the stars, at the corroboree camp and on horseback, mustering cattle from Anmatyerr country to Mt Isa.27 In contrast; Bardon’s creative vision had been forged under Ellen Waugh’s tutorship at Alexander Mackie’s Teachers College in Sydney. There, Bardon was exposed to the intellectual/haptic dichotomy theorised by Viktor Lowenfeld (1939).28 Bardon identified as an instinctual artist. Moreover, he projected Lowenfeld’s subjective notions of hapticity onto Aboriginal art, emphasising the value of authenticity and intuition over calculation and contemporaneity.29

Bardon was also an aspiring filmmaker and photographer. Empowered by available technology, including a 16mm Paillard-Bolex spring loaded motion camera, and 35mm Pentax stills camera, Bardon created a rich visual record of several novel modes of cultural expression as they emerged at Papunya.30 Inevitably, for a newcomer schooled in subjective observation, Bardon recorded developments from a personal perspective; events that occurred outside his gaze, while absent from his compelling record, were none-the-less consequential. Thus, important developments, many of which were generated by Indigenous proponents, escaped his notice.31

Critically, Bardon was alive to the potential for murals to represent community aspirations. As a student of art, he would have come across the work of the Mexican Marxist Diego Rivera, famous for his revolutionary murals. Bardon may also have been aware of the upsurge in mural painting in the United States, a phenomenon that can be traced to William Walker’s Wall of Respect (1967) a visual statement that became a focus for the Black Power movement in Chicago.32 From my initial research, Australian murals with an equivalent revolutionary purpose appear to have been few and far between, despite the strength of the Communist Party of Australia in the mid-20th century. One notable exception was a collaborative mural project, undertaken “in an open-ended creative process,” and coordinated by Rod Shaw at the Waterside Workers Federation building, 60 Sussex Street, Sydney. Evolving incrementally from 1953 until the early 1960s, the mural celebrated the hard-working solidarity of the “warfies.”33 In contradistinction, most murals in mid-century Australia appear to have been commissioned by companies and educational institutions from established artists, to reinforce the status quo. The mural project initiated by Bardon at Papunya is therefore all the more remarkable, because it precedes the proliferation of proletarian murals celebrating workers, women, Indigenous rights and local history, at locations including Redfern, Northcote and Prospect during the 1980s.

THE PAPUNYA MURALS

Bardon, and his Headmaster, Fred Friis are emblematic of the changing educational order in the Northern Territory, which sought to soften the strict divide between white teachers, students, and their Indigenous parents. Yet, this new guard appeared powerless to counter the alienation expressed by some prospective students. Vandalism was rife in the administrative hub at Papunya and the school was not exempted from attack. The library had recently been torched and mud thrown at classroom walls. Desperate for a solution, Friis elicited Bardon’s assistance. Rather than signs or fences, Bardon suggested murals be painted for the people and by the people—and the wisdom of his advice rings true even 50 years after the artworks were commissioned.34

Busy with artistic projects since his arrival at Papunya in February 1971, Bardon’s awareness of the nascent art movement at Papunya grew incrementally.35 Among the first of the prospective painters he encountered were the school groundsmen, Bill Stockmen Tjapaltjarri and Long Jack Phillipus Tjakamarra. Both were capable family men, who had arrived at an accommodation with the assimilationist policy through the exchange of labour for wages, and the advantages that accrue with being on the inside of the colonial project. Significantly, Kaapa was not among their number, he was busy nearby, with his own project in the old settlement office.36 Regarded as a ‘troublemaker’, Kaapa had previously been employed as a groundsman but had been sacked for stealing brushes from the art room.37

Phillipus and Stockman painted the first murals, featuring “Widows” and “Wallaby” icons on masonry walls under the veranda on the south-eastern wing of the school.38 A little later, Nosepeg Tjunkata Tjupurrula and Willy Tjungurrayi painted the sinuous forms of two snakes on the remaining section of the same wall, while Johnny Warangula applied “Water” designs to adjacent columns.39 The final work in the sequence, the now famous Honey Ant mural occupied an expansive central wall near a breezeway. Prophetically, Keith Namatjira, son of Albert Namatjira, the founder of modern Aboriginal art in Central Australia, was engaged by Bardon to prepare the surface on which the concluding mural was to be painted.40 Significantly, Kaapa and Keith Namatjira were classificatory cousins and good friends.41 It is possible therefore that Keith informed Kaapa of the large flat surface at the school, inadvertently facilitating a transition from his father’s representational realism to a symbolic regime that could communicate Indigenous sovereignty.42

PAINTING UNDER THE VERANDA

The mural project began haltingly, in June 1971, then gained pace as further men were attracted to the school, critiquing what had been done and discussing future themes.43 All that time Kaapa was developing a revolutionary new way of representing ceremony at a studio he had established at the old settlement office within Papunya’s administrative hub, just 150 meters from the school. Joined by peers, from several language groups, the men recalled religious icons from a vast swathe of Country, painted on materials salvaged from the detritus of the settlement.44 The confluence of imagery, produced by artists at Kaapa’s studio and the school suggests that the outpourings at both sites were, in effect, part of the same overarching project. Although details of the transmission of ideas and materials between Kaapa’s studio and the school are not recorded, several of same protagonists were involved in both ventures. Long Jack Phillipus for instance, created the Widows Dreaming mural on the Besser brick wall at the school, and his Widows Dreaming (1971, Art Gallery of South Australia) employs near identical imagery, on a scrap of recycled building material.

While it is clear that developments at Kaapa’s studio and the Papunya School gained momentum in the winter of 1971, the exact order in which specific works were created can only be speculated upon.45 Yet, such sequencing is deemed crucial to the constitution of art history, at least in the Western academic tradition, where precedence is regarded as critical. Rather than seeking to identify a paramount antecedent however, I suggest the concurrence of related events—at both workplaces—signals a shift in colonial relations: from the assimilation of “Aborigines” into the “European” mainstream, to the assertion of Indigenous rights anchored in an enduring association with the land.

While the exact date of production for particular works is impossible to ascertain, the approximate dates of related events is known.46 Critically, the events at Papunya cannot be viewed in isolation from incidents at adjacent communities during this period of radical social upheaval.47 Important shifts in power relations were underway across Central Australia.

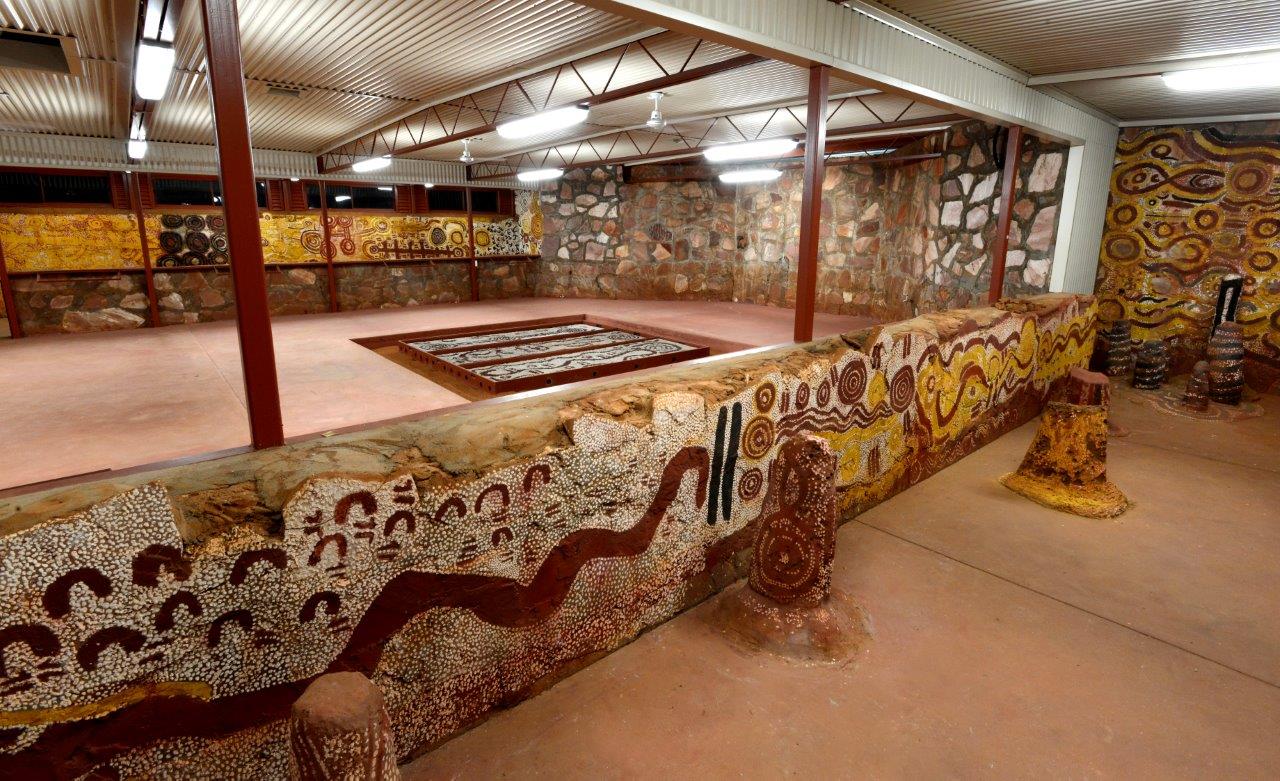

A key event on the Central Australian cultural calendar was the Yuendumu Sports, known locally as “the Aboriginal Olympics”—this unmissable occasion was held annually on the first weekend of August. In addition to the usual rounds of football, softball and spear throwing, the 1971 sports weekend featured the official launch of the Yuendumu Men’s Museum.48 In his opening address, Harry Jagamara Nelson made special mention of murals painted on the internal walls of the museum.49 The eight murals, each of which represents the Dreaming of a nearby estate, were applied to the roughly rendered rock surface of the eastern and western wings of the museum. Louvered screens and lockers, in which sacred objects from the sites depicted on the murals were stored, separated the museum’s two wings. An expansive ground mosaic was created on the floor of a large square room at the centre of the building.50 The museum’s curator, Darby Jampijinpa Ross and his peers, created the ground mosaic and murals in 1971 as the new approach to painting gained traction at Papunya.51 Significantly, the Yuendumu muralists were of similar age and comparable ceremonial stature to the men who founded Papunya Tula art. The murals remained unchanged but rarely visited, secure in the solid stone museum for many years after their creation.52

Both Bardon and Kaapa attended the Yuendumu Sports in 1971. Bardon however may not have seen the murals, as louvered screens obscured the eye-line to the unlit periphery of the museum. Kaapa Tjampitjinpa, whose country is closer to Yuendumu than it is to Papunya, was a familiar presence at the community.53 The significance of his agency as a conduit between the mural projects in both communities, while not documented in detail, cannot be discounted.54 Dick Kimber was also at the launch and recalls Kaapa being among a large contingent of men, painted with the totemic designs, who performed a “revolutionary dancing that all men, women and children could see.”55 Cultural change was underway across the region highlighted by the dramatic events at the Yuendumu Sports weekend.

The Yuendumu murals invite comparison with the Papunya School project. The murals at the Yuendumu Men’s Museum were created in a darkened atmosphere; a space restricted to Aboriginal men.56 In contrast, the Papunya school murals were designed for public viewing. Presented in a light-filled pedagogical space, and available to be seen by uninitiated girls and boys, the Papunya murals are a corollary for the openness of the “revolutionary dancing” observed by Kimber at Yuendumu sports. Whereas a cache of “dangerous” ceremonial objects supplemented the murals in the Yuendumu museum, the Papunya murals were visible outside schoolrooms and adjacent to a library, the archetypal repository of whitefella law. Despite significant differences, both projects can be interpreted as proactive responses to the social transformation that was gaining momentum across Central Australia.

Although the Yuendumu and Papunya murals were envisioned for different audiences, the fact they were made in the same year, in proximate communities is significant. Moreover, the iconography used in both series is drawn from the same sacred well of designs associated with ceremonies conducted for the instruction of post-initiation novices. The concurrence of comparable murals suggests an upwelling of confidence in regional cultures, emblematic of the zeitgeist, and not confined to Indigenous Australia. Composed of culturally specific icons associated with the immediate totemic landscape, both sets of murals speak of a moment when the reach of modernity became global, affecting creative thought at remote Aboriginal communities on the frontier of colonial governance—as surely as it did at Melbourne’s Pram Factory experimental theatre, or Sydney’s Yellow House Artist Collective. The Gurindji leader, Vincent Lingiari travelled to southern cities that same year to advocate for land rights, a visit that built towards the moment, when on 16 August 1975, Prime Minister Gough Whitlam ceremoniously poured red earth into Lingiari’s hands at Wave Hill Station, events that prompted Kev Carmody and Paul Kelly to write the anthem, “From Little Things Big Things Grow.”57

MAKING THE HONEY ANT MURAL

The Widow’s, Wallaby, Water and Snake Dreaming murals at the Papunya School were completed before the Yuendumu Sports weekend and were well received by senior custodians and school authorities alike. The momentum surrounding the school mural project continued to grow as other men, with an interest in Country represented entered the school, to inspect the work and sing associated verses.58

Kaapa had kept his distance during the shortest days of winter, letting other men take the lead at the school while he worked on his own paintings at the old settlement office. Meanwhile, excitement grew as the days stretched and Keith Namatjira prepared the school’s longest wall. The naked-white surface at the heart of the school called out for an important design.59 It was at this juncture when Bardon recalled meeting Kaapa for the first time, accompanied by his good friend, Mick Wallankarri Tjakamarra, one of the oldest men at Papunya and an authority for the site on which the settlement was established.60

Kaapa and Wallankarri approached Bardon at his flat. They had a well-considered plan, drafted on a small piece of paper. To achieve their end, they would need to convince Bardon, who later described the exchange that ensued:61

Kaapa secretly handed a piece of paper to Old Mick Tjakamarra and kept whispering and making signs to Old Mick to hand the paper to me and there were gestures, and coughing, and clearing of throats, as at last the paper was put in my hand.62

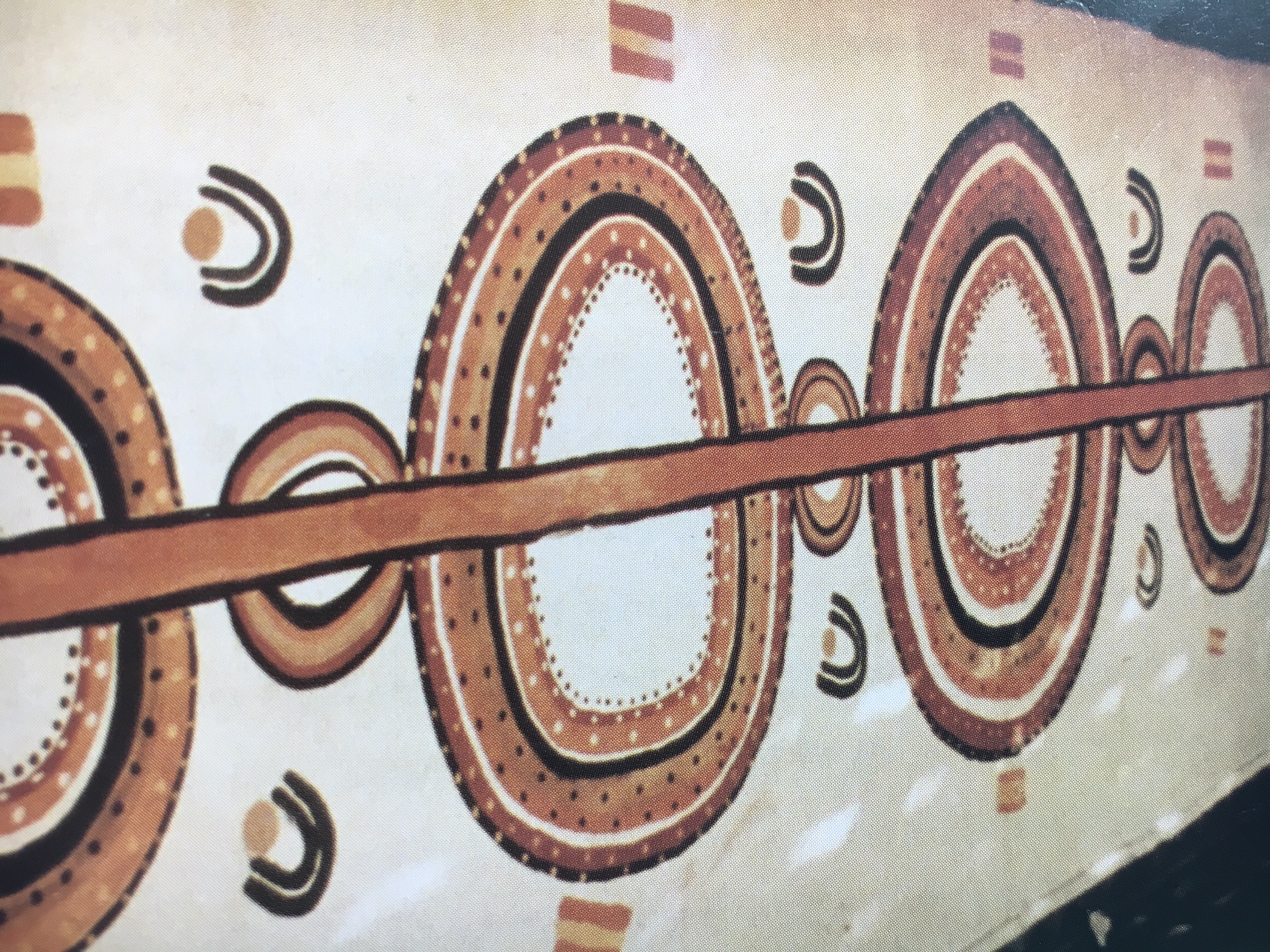

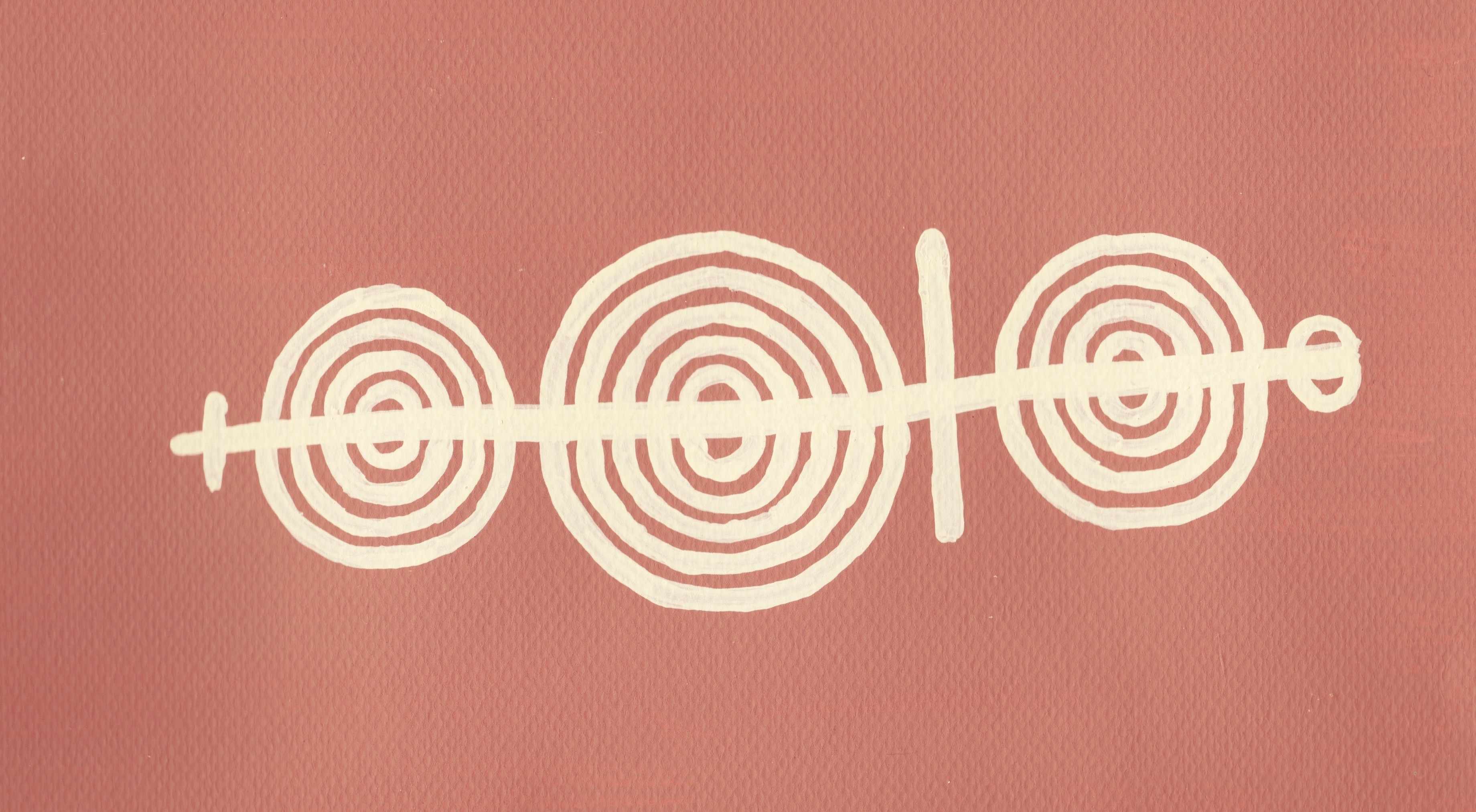

The image on the original scrap of paper (now lost) was based on episodes of the Tjala songline, as the Honey Ant sire was approaching Papunya. The site-travel motif chosen for the mural consists of two major elements. Long parallel lines show the subterranean tunnels of the Honey Ant ancestors, in this case from Tatata in the west to Papunya, while major sites along the songline are indicated by sets of concentric circles, intersected by those lines. The largest set of concentric crescents, in the centre of the design, signifies Papunya, the main place.63

The design is developed from those used on various surfaces during ritual. It is similar to the signs painted on kutitji (softwood shield), presented to novices at ceremony. The design also closely resembles icons that adorn the walls of a rock shelter in distant Kaytej country, demonstrating the reach of desert iconography.

Rock art is regarded as an important source of contemporary desert painting, but to my knowledge, there are few examples of major paintings around Papunya. The most notable exception is the colossal representation of Yarripiri, an Inland Taipan painted on the extensive rock shelter at Ngama in Southern Warlpiri/Ngaliya country. It is certain that Kaapa would have known the site, for Ngama is very close to his father’s country.64

Comparable designs are also engraved on tywerrenge—the sacred objects regarded as the embodiment of the Ancestral Heroes who shaped the land.65 The relationship between the design of the mural and tywerrenge is neither casual nor inconsequential. When interviewed about his recollections, headmaster Friis remembered being taken to a nearby storehouse at a sacred site where Kaapa extracted a “big rock.” The tywerrenge was taken back to the school where it was unwrapped, Kaapa proclaiming “this is what we are going to paint on it.”66 While the chosen icon is only one of the several designs associated with local Honey Ant ancestors, it is composed of essential elements that convey the travels of Honey Ant ancestors to Papunya.67

It is clear from Bardon’s account that Kaapa was already familiar drawing with pencil on paper, more significantly, he understood how to pitch a concept to whitefellas with a scaled plan. Kaapa’s design addressed the proportions of the intended wall with precision. With Bardon’s approval secured, Kaapa laid out the key structural elements of the Honey Ant Mural on the rendered brick wall with confidence and unabashed fluency.68

Who’s Mural?

From the moment of his first meeting with Bardon, Kaapa managed the process at artistic, practical and strategic levels. Not only was he the leading hand, Kaapa also conducted negotiations with traditional custodians, Tom Onion, Mick Wallankarri and Bert Nananana, and the school authorities, Fred Friis and Geoff Bardon.69 Resolving the mural’s final detail required a delicate balancing of various intercultural interests.

The first version of the mural caused consternation among senior custodians. Evidently, paired arcs, painted at intervals between the site-travel motifs were thought to resemble too closely the sacred body paint of ancestral Tjala, and required modification. Accordingly, in the next iteration, Kaapa replaced paired arcs with a figurative representation of the Honey Ant sire. While the custodians appeared content, Bardon, who styled himself, as the “art master” was displeased.70

Kaapa’s use of realism to represent the honey ants, did not match Bardon’s aspirations for authenticity: “Are these ants proper blackfella honey ants?” he demanded, insisting, “Nothing is to be whitefella.”71 Writing years after the event Bardon still appears surprised by Kaapa’s response to his abrupt intervention:

Then all the work stopped, and six other painters crowded about to look at the honey ants, and Kaapa Tjampitjinpa seemed to have an answer even before words were said. I remember how he liked to push himself towards you with a distinct movement of his face, a roguish all-knowing look, all quick and right.72

Kaapa retorted with insouciant ambiguity: “Not Ours, Yours, We paint yours.” Confident in his role as arbiter of Aboriginality, Bardon confirmed, “Blackfella honey ants.”73 Obligingly, Kaapa then painted out all remnants of Western realism, and replaced those images with autochthonous U-shapes to represent the Honey Ant ancestors.74 This third version employs a more oblique reference to the Honey Ant sire, satisfying all stakeholders. Bardon subsequently described the mural’s completion as a “moment of glory for the Western Desert people.” Going further still, he pronounced the Honey Ant mural as “the beginning of the Western Desert painting.”75

Many of those who hope for a single moment of genesis have grasped at Bardon’s claim for priority. While acknowledging Kaapa as a “classically brilliant artist,” Bardon evaluates the significance of the mural to Indigenous custodians with colonial munificence, “the Aboriginal men saw themselves in their own image and before their very own eyes, and upon a European building. Truly, something strange and marvellous had begun”.76 Bardon’s narrative is recited ceaselessly in subsequent newspaper articles and validated in much of the art historical literature.77

The renown achieved by the Honey Ant mural is noteworthy, given its short-lived presence in a school quadrangle, at a remote settlement some 250 kilometres west of Alice Springs. I suggest its status can be attributed to the effectiveness of Bardon’s advocacy, for few outside the school community saw the mural in situ before the mural was over-painted by a routine maintenance crew in 1974. Rather than being a deliberate act of vandalism, Johnson considers the mural’s obliteration to have been an act of careless disregard.78 Significantly, Bardon’s claim for the lost mural discounts the importance of related events that occurred as winter turned to spring in 1971.

PRIDE AND PRECEDENCE

The Honey Ant mural came about as a result of the collaboration between Indigenous and non-Indigenous authorities, a remarkable achievement given these events occurred at the tail end of the assimilation era, when Indigenous people were obliged to adopt the habits and values of the colonisers. Bardon’s role as the sensitive facilitator of “Western Desert painting” is routinely celebrated, while the Kaapa influence, if acknowledged at all, has been underplayed as just one of the men who rose to Bardon’s challenge. It was Vivien Johnson, writing in 2010, who would position Kaapa as the leader of a nearby studio, as producing sophisticated representations of Indigenous ceremony before the Honey Ant Mural was conceived. Rating Kaapa’s early paintings as both distinct and essential to formation of “Western Desert painting,” Johnson reconstructed much of what is now known of the short-lived movement she dubbed, “The School of Kaapa.” 79

The commercial potential of Kaapa’s initiative was first realised when Jack Cooke, a visiting District Welfare Patrol Officer noticed a painting, now known to be Ceremonial Scene (Mikantj) (1971, Museums and Art Galleries of the Northern Territory), for sale at the Papunya store.80 Excited by the display of indigenous entrepreneurship, Cooke searched for the artist, locating Kaapa at the old settlement office. With Nosepeg’s assistance, Cooke arranged a consignment of paintings to be delivered to his office in Alice Springs. Fatefully Cooke entered three of Kaapa’s works into the forthcoming Caltex Northern Territory Art Award.

To the astonishment of those assembled at the Alice Springs Golf Club on Friday 27 August, Kaapa was announced as co-winner of the award that to that point had been the preserve of local artists painting in the European tradition.81 As well as Kaapa’s prizewinning Men’s Ceremony for the Kangaroo Gulgardi (1971, Araluen Arts Centre), Cooke sold a handful of Tjampitjinpa’s paintings to associates, which together with the prize money netted Kaapa approximately $750. News of the prize and the allied sales filtered back to Papunya, exciting would-be artists: the custodians of esoteric knowledge upon which further paintings could be based. The curator and art historian, Luke Scholes emphasises the return on Kaapa’s paintings “was an extraordinary amount considering the average income amongst the Aboriginal population in Papunya at the time was $5.50 per week.” Scholes claims that “Kaapa’s win was the watershed moment in the history of the Papunya art movement and triggered a surge in interest amongst the fledgling groups of artists working in Papunya.”82 While it is highly likely that the production of Kaapa’s prize winning painting and the mural project overlapped, I agree with Scholes’ assessment that Kaapa’s financial success was the catalyst that set a number of Papunya residents on the path to become committed painters.

Kaapa’s success appears to mark the end of the period where drawings were done voluntarily on paper on Bardon’s verandah, or as murals on school walls.83 Blindsided by Cooke’s initiative, Bardon returned to the nascent painting project with increased determination, organising basic materials for enthusiastic painters. Critically he also identified market opportunities beyond the confines of the settlement. By his own admission, Kaapa’s success prompted Bardon to “apply concentration towards the art work of the men to raise technical standards, “purifying” the mythology and [providing] general encouragement…”84 The extent to which Bardon affected the artists’ approach to “mythology,” while prompting questions about the intervention of external facilitators in Indigenous art, is beyond the scope of this essay.

The narrative of the Papunya School murals features in each of Bardon’s three monographs, and his role in their creation becomes increasingly influential with each telling.85 The most comprehensive account is published in Bardon’s posthumous opus (2004) in which eighteen photos of the murals are reproduced. Bardon’s dreamy images suggest the events occurred in a liminal zone, beyond current understanding. Distanced by the camera, the muralists appear either in silhouette unaware of the Bardon’s gaze or staring back blankly to the photographer whom they seem not to recognize. The film, presumably Kodachrome stock, renders the men’s dark features indistinct in contrast to the overexposed brilliance of the white walls on which the murals were painted. In this regard, it is the media (1970s film stock) rather than Bardon’s stance that robs the muralists of their agency.86 Singularly, Kaapa engages the photographer, pointing to the centre of a roundel, as if to say, “Look deeper. Look into the earth.” Kaapa’s gesture demands that attention be paid to the mural’s incontrovertible purpose.

Rather than acknowledging simultaneous developments at Kaapa’s studio in Papunya and the Men’s Museum in Yuendumu, Bardon habitually locates himself at the epicentre of Indigenous cultural revival, dismissing the contribution of others to the creation of a revolutionary new idiom at Papunya.87 The anthropologist and public intellectual, Marcia Langton writes of recurring instances whereby “the main drama is the stance of the Western Observer,” a phenomenon she has seen played out across Indigenous/colonial relations, especially in the artistic domains.88 Yet, despite Bardon’s claim as auteur and principal witness, his role, for too long, escaped serious critique.

The art historian Ian McLean contends that “No Matter how much the Western Desert art movement is a historical formation, its mythic presence, first articulated by Bardon, looms larger than ever over its reception at popular and critical levels.”89 McLean concludes his essay The Gift that Time Gave: Myth and History in the Western Desert Painting Movement with the following rhetorical assertion:

Here [in the early years of Papunya painting] was something exceptional, great and unexpected, something that demanded its own myth. It will be some time, I suspect, before the full history of the movement becomes visible, but even then the myth will prevail. Modern historians might make their names as spoilers of myths, but who in the art world would want to de-mythologise Papunya Tula?

I do not resile from the central purpose of this essay, which is to de-bunk myths that enveloped the emergence of painting at Papunya. The popular fable, with Bardon as omnipresent auteur is misleading, for it denies the wily political strategy and hard intellectual work required to extract traditional icons from their ceremonial context so as to produce powerful and aesthetically balanced images on a introduced rectangular format.90 The ceaseless recitation of Bardon’s self-dramatising account has diminished the critical roles played by Indigenous and non-Indigenous protagonists alike. Alert to distortions perpetuated through the “European gaze,” Vivien Johnson describes the uncritical repetition of what she terms “Geoffrey Bardon’s foundation story of Papunya Tula Artists,” writing the myth has been “told so intensely and has been re-told so often and so widely, that now it has almost the force of a Dreaming narrative itself.”91 Uncritical repetition of the Bardon-centred account is essentially a-historical, for it veils the actions of sophisticated political players, and misreads the broader social context in which events occurred.

The relationship between the school murals and the work produced at the old settlement office is relevant, for this is the critical moment when the sacred iconography for Country emerged to become publicly visible at Papunya.92 Whereas, Bardon considered the mural project was “a moment of glory” that signified the quickening of the painting movement at Papunya, I regard Kaapa’s studio project as equally influential, for despite having occurred in a more secluded location, the sale of a batch of Kaapa’s painted boards catalysed the professionalisation of painting at Papunya.93

My aim is not to dismiss Bardon’s contribution, but to recognise the Indigenous cultural brokers, who knew enough about how whitefellas think to take strategic advantage of their moment as cracks emerged in the mantle of the infrastructure of assimilation.94 Kaapa and Wallankarri stepped forward with a well-considered plan when a blank space was prepared for inscription at the pedagogical heart of the settlement.95 Furthermore, as Scholes has established, white administrators associated with the assimilation policy actively supported the burgeoning painting movement before, during, and after the mural’s creation.96 A movement was underway, and Bardon felt its tug. In fact, he was so swept up by the tide of change that he could not sense that others were also instrumental in its effect.

It is likely that Kaapa was not so much flattered to have his image emblazoned on the wall of a “European building,” but more exactly, he was at that moment taking possession of the building. Just as he stole brushes from the art room for his own purposes, Kaapa inscribed the building with icons that from the local perspective could be read as the Indigenous equivalent of deeds of title. Kaapa manifests the latent power of the ancestors, dwelling in their darkened chambers under the earth, in the bright light on the surface of the colonial settlement.97

Kaapa’s unruly agency is critical to the narrative of desert art, and the fact that he was the leading hand on the Honey Ant mural must be recognised, for his proactive stance inverts received assumptions that the image was conjured by Bardon’s sensitive intervention. It is no coincidence that Kaapa inserted himself as the artist of the most ambitious and prominent mural. Kaapa was the theorist behind the representation of ceremony on a portable medium and his painting, Man’s Ceremony for the Kangaroo, ‘Gulgardi’ was acclaimed at the Caltex Northern Territory Art Award in the same month as he completed the mural. Kaapa was without doubt the first master of Papunya Tula art, and August 1971 was the defining moment when his intercultural mastery surfaced to become an irresistible force.

MEANING AND THE HONEY ANT MURAL

The Honey Ant mural was a public manifestation of the ancient ceremonial cycle of earth and blood. Yet it was created in the here and now as a statement of political intent—the assertion of Indigenous power. Rather than producing an epiphany for Indigenous observers, as Bardon would have us believe, I argue the mural can be compared to a political poster. Pasted on a wall the Honey Ant icon demands recognition of pre-existing rights.

Inscribed on the white wall of a “European building,” the mural’s key elements signify the enduring subterranean architecture of the Honey Ants’ ancestors over which the settlement is sited. The Honey Ant sire and his attendants travelled within the underground tunnel signified by the horizontal band that runs the length of the mural wall. That tunnel demonstrates how Papunya is connected to other sites across an unbounded land. The tunnel penetrates further sites (indicated by the looping concentric circles) where the honey ants rested or went about the ceremonial business. The Honey Ant Dreaming mural is a potent articulation of the earthy substance of land-based sovereign rights; it is a significant tranche in an ongoing struggle for recognition of the indivisible connection of Indigenous people to the land.

The Honey Ant mural was a powerful proclamation of the significance of place, Papunya, and that site’s connection to the broader landscape. Kaapa, and the custodians who endorsed his representation of the Tjala Dreaming, intentionally revealed the power of earth that had hitherto been considered inert by the succession of missionaries, pastoralists and government officials.

PRESENT SIGNIFICANCE OF THE HONEY ANT MURAL

Now, half a century after their creation, the Papunya school murals retain their significance. The subject of the largest mural, the Honey Ant—variously referred to as Tjupi, Tjuupi, Tjala and Yirrampa—persists as a symbol, almost a brand for the Papunya community, as well as being the major local totem. In a recent visit to the community to discuss this research with the children of the founding artists, now grandparents around my age, I snapped a handful of images of honey ants, a visual vernacular perpetuated at the Papunya School.

The major wall, on which the original Honey Ant Mural was painted, remains dedicated to political statement. William Sandy painted the current mural shortly before the Northern Territory National Emergency Response (2007). More commonly known as “The Intervention,” the Federal Government overruled the autonomy of Aboriginal communities, effectively erasing the practice of bi-lingual education from most Northern Territory schools.98 Sandy’s mural represents the potential of “two-way” teaching, when black and white teachers cooperate in the classroom. Oversized, realistically painted honey ants confirm the local context. Rather than summoning the repatriation of Kaapa’s original mural, the current painting represents the aspirations of contemporary leaders at Papunya, including the children of the original muralists, Punata Stockman Nungurrayi and Charlotte Phillipus Napurrula, articulating the benefits of a “two-way” education system.99

Residual elements of the first murals can still be seen through cracks in the plaster at Papunya. Punata Stockman and Charlotte Phillipus are old enough to have been students at the school when the murals were freshly painted; they know what lies under the accretions of time. Yet they remain unwilling to commercialise such traces. Rather, they hold out for a more expansive recognition of their seniority, custodianship and knowledge.100

Conclusion

Community-based projects were a democratising feature of the 1970s, and in this, the Papunya murals are emblematic of their time as people who had been subjugated, sought to subvert entrenched power relations. Yet time runs differently in the desert and knowledge is revealed slowly if at all. This is buried country whose inertia is inextricably tied to the persistence of its land-oriented culture.

Despite the antiquity of Central Australian belief, Papunya was, in the 1970s, a site of remarkable contemporaneity, and the ground-breaking paintings that emerged from this community of just a thousand people exerted a disproportionate effect on national and global culture. Kumantjayi Long put it best when he described how it “started like a bushfire this painting business, and it went every way, north, east, south, west. Papunya in the middle.” 101 The exquisitely resolved paintings that have emerged from Papunya over the last 50 years continue to astound. Papunya Tula art breathed new life into contemporary painting, an artform that the conceptualists of the 1970s had declared dead and finished!

It is fitting that the Honey Ant mural is now recognised as a “Defining Moment” of contemporary Australian art, for it exemplifies the expanded field that has liberated our national culture from the shackles of the western cannon. The Honey Ant mural was ephemeral and its influence more mercurial than the painted boards by Kaapa and his followers, images that persist as objects. The murals’ absence makes it more susceptible to myth making than the thousand or so “Papunya boards” created by the yardsmen and their peers during 1971 and 1972, objects that are prominently exhibited public galleries and traded lucratively on the secondary art market. Taken together however, the school murals and the “Papunya boards” constitute a monument that must be reckoned with when a comprehensive history of Australian art is written.102

The Honey Ant mural was not made on the first day of creation, but at the beginning, when Kaapa was already hard at work formulating a new way of representing his culture on materials salvaged from the crumbling edifice of the assimilation policy. The mural is significant for it illustrated the substance of Aboriginal belief at both literal and metaphoric levels. Its presence and scale, as a public statement on a “European building,” demonstrated that the men who worked at the school, were also custodians of formidable sacred knowledge. It is unsurprising therefore, that each of the muralists went on to achieve national and international recognition. A handful of archival images of the Honey Ant mural provide compelling evidence of its quality as an icon. It epitomises the symmetry, balance and dynamism of Indigenous aesthetics—qualities that continue to pervade the national consciousness, insisting that the earth on which we tread is animated by living culture.

20.11.2020

-

Seamus Heaney, “Squarings XLVIII ,” in New Selected Poems, 1988–201 3 (London: Faber and Faber, 2014), 60. ↩

-

An earlier iteration of this paper was presented on 29 April 2019 as a lecture in the Defining Moments: Australian Exhibition Histories 1968–1999, at Australian Centre for Contemporary Art. The author acknowledges the assistance and advice of Cecilia Alfonso, Philip Batty, Max Delaney, Jason Gibson, Vivien Johnson, Philip Jones, Yolande Kerridge, Gloria Morales, Dennis Nelson Tjakamarra, Narlie Nelson Nakamarra, Charlotte Phillipus Napurrula, Helen Puckey, Luke Scholes, Punata Stockman Nungurrayi, Liz Suda and the Papunya community. ↩

-

Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Defining Moments: Australian Exhibition Histories 1968–1999, [https://acca.melbourne/series/defining-moments/]{.ul} accessed 5 July 2021. ↩

-

Vivien Johnson, The Streets of Papunya: The Re-Invention of Papunya Painting (Randwick, N.S.W.: NewSouth Publishing, 2015), 65. ↩

-

Janet Maughan et al., Dot and Circle: A Retrospective Survey of the Aboriginal Acrylic Paintings of Central Australia, exh. cat. (Melbourne: Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, 1986), 36. ↩

-

The creation of the mural is described in Geoffrey Bardon, Aboriginal Art of the Western Desert (Adelaide: Rigby, 1979), 13–14. ↩

-

Tjala is just one name used for the species, Camponotus inflatus. Other names used at Papunya include ngari, tiwirrpa, purrarra, yirrampa and tjuupi (more recently written tjupi). K. C. Hansen and L. E. Hansen, Pintupi/Luritja Dictionary, third edition (Alice Springs: Institute for Aboriginal Development, 1992), 81. ↩

-

Richard G. Kimber, “Papunya—the dialogue of the country,” in Wildbird Dreaming: Aboriginal Art from the Central Deserts of Australia (Melbourne: Greenhouse, 1988), 73-77. Also see a description of the significance of termites, a comparable underground dwelling insect with considerable religious significance, Richard G. Kimber, “Mosaics you can move,” Hemisphere, 21, no. 1, (1977): 6–7. ↩

-

Luritja is now accepted as the lingua franca at Papunya. ↩

-

Jeremy Long personal correspondence 10 March 2016. ↩

-

Vivien Johnson, Lives of the Papunya Tula Artists (Alice Springs: IAD Press, 2008), 19; 44. ↩

-

H. Penny et al., Papunya: History and Future Prospects, a report prepared for the Ministers for Aboriginal Affairs and Education, Unpublished Manuscript (1977), 9; Tim Rowse (ed.), Contesting Assimilation (Perth: API Network, 2005), 2. ↩

-

Johnson, Lives of the Pupunya Tula Artists, 2008, 9. ↩

-

Mike Smith, The Archaeology of Australia’s Deserts (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 208–211. ↩

-

Kimber, “Papunya—the dialogue of the country,” 1988, 67. ↩

-

The ceremonies were performed for Strehlow’s camera at Wolatjatara ceremonial camp, a few kilometers north of Alice Springs. The ceremonies are of a restricted nature. The author was allowed to view them because of his enduring association with the senior custodians and familiarity with protocols associated with the discussion of restricted ceremony. Theodor George Henry Strehlow, Yerrampe, and Possum at Wolatjatara Ceremonial camp, Alice Springs: Strehlow Research Centre, 1955. ↩

-

Johnson, Lives of the Papunya Tula Artists, 2008, 4–5. ↩

-

For biographies of Kaapa Tjampitjinpa and Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri see, Johnston, Lives of the Papunya Tula Artists, 2008, pp. 17–20; 44–46; John Kean: in Judith Ryan and Philip Batty, Tjukurrtjanu: Origins of Western Desert Art, exh. cat., (Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2011), 104–106; 180–182 [respectively?]. Yes ↩

-

Penny et al., Papunya: History and Future Prospects, a report prepared for the Ministers for Aboriginal Affairs and Education, 1977, 37–38. ↩

-

Penny et al., 1977, 88–105. ↩

-

‘When used in Aboriginal English, the term ‘myall’ refers to a person with less experience of non-Indigenous ways than the speaker. It can also applied as a pejorative to refer to someone who knows nothing of the subject. ‘Myall’ comes from the Dharug language of the Sydney area where it means ‘stranger’. ↩

-

The camp’s name refers to the site of an unsuccessful ‘piggery’ established in the 1960s. ↩

-

Geoffrey Bardon and James Bardon, Papunya: a place made after the story: the beginnings of the Western Desert painting movement (Carlton: Miegunyah Press, 2004), 17–18. ↩

-

The anthropologist Peter Sutton has been critical of his own, and his peer’s naïve support of Indigenous cultural practices during the 1970s and 1980s, that with the benefit of hindsight has been of little benefit to the people who it purported to assist. Peter Sutton, The Politics of Suffering: Indigenous Australia and the End of the Liberal Consensus (Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne University Press, 2009). ↩

-

Luke Scholes, “Unmasking the myth: the emergence of Papunya painting.” In Tjunguṉutja: from having come together, ed. Luke Scholes (Darwin: Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, 2017), 127-161. Vivien Johnson, Once Upon a Time in Papunya (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2010), 111–115. ↩

-

Johnson, Once Upon a Time in Papunya, 2010, 11–40; John Kean, Dot, Circle and Frame: how Kaapa Tjampitjinpa, Tim Leura, Clifford Possum and Johnny Warangula created Papunya Tula art, Doctoral Thesis, University of Melbourne, 2020.

[http://minerva-access.unimelb.edu.au/handle/11343/242476]{.ul}, 141. ↩

-

Johnson, Lives of the Papunya Tula Artists, 2008, 19. ↩

-

See Viktor Lowenfeld, The nature of creative activity: experimental and comparative studies of visual and non-visual sources of drawing, painting, and sculpture by means of the artistic products of weak sighted and blind subjects and of the art of different epochs and cultures, New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1939. ↩

-

Johnson, Once Upon a Time in Papunya, 2010, 116-17. ↩

-

Bardon and Bardon, Papunya: a place made after the story, 2004, 9. ↩

-

The subject of the second half of the author’s doctoral thesis, Kean, Dot, Circle and Frame, 2020. ↩

-

See Abdul Alkalimat et al., Wall of Respect: Public Art and Black Liberation in 1960s Chicago (Evanston Il: Northwestern University Press, 2017). ↩

-

Margo Beasely, Wharfies : a history of the Waterside Workers’ Federation of Australia (Rushcutters Bay, N.S.W. : Halstead Press in association with the Australian National Maritime Museum, 1996), 162. ↩

-

Friis cited in Scholes, “Unmaksing the Myth,” 2017, 131. ↩

-

Bardon and Bardon, Papunya, 2004, 3–11. ↩

-

Johnson, Once Upon a Time In Papunya, 2010, 28–29. ↩

-

Bardon, Pupunya Tula, 1991, 36–41; 108. ↩

-

These titles were applied by Bardon, and can be more accurately referred to as Women and Mala Hare Wallaby Dreamings. Bardon and Bardon, Papunya, 2004, 16. ↩

-

Probably Kuniya Kutjarra, (two pythons) Bardon and Bardon, 2004, 19. ↩

-

Bardon and Bardon, 2004, 14. ↩

-

Johnson, Once Upon a Time In Papunya, 2010, 29. ↩

-

Kaapa’s eldest son Keith Kaapa was named after Keith Namatjira. Kean, Dot, Circle and Fram, 2020, 105-107. ↩

-

Bardon and Bardon, Papunya, 2004, 12–19. ↩

-

Mary White cited in Scholes, “Unmasking the Myth, 2017, 134. ↩

-

For the most accurate account of the events of this period see Johnson, Once Upon a Time In Papunya, 2010 and Scholes, “Unmasking the Myth,” 2017. ↩

-

For instance, seven of Kaapa boards, painted at the “old settlement office” were taken to Alice Springs after 6 July 1971. More pictorially ambitious than comparable works by his peers, these works constituted the first consignment of recognisably “Papunya style” paintings to leave the community, Scholes, “Unmasking the Myth,” 2017, 132–33. ↩

-

See Bardon, Aboriginal Art of the Western Desert, 14; Geoffrey Bardon, Papunya Tula: Art of the Western Desert (Ringwood: McPhee Gribble, 1991), 18-9; Bardon and Bardon, Papunya, 2004, 12–19. ↩

-

Kieran Finnane, “Beginnings of contemporary Western Desert art.” 31 July 2015 https://alicespringsnews.com.au/2015/07/31/yuendumu-writes-new-chapter-on-the-beginnings-of-contemporary-western-desert-art/ [02.11.2020]. ↩

-

Harry Jagamara Nelson (1946-2021) passed away during the preparation of this essay. He had been an important politician, go-between and cultural custodian at Yuendumu since the 1970s. Nelson was the older brother of the well-known Papunya painter Michael Jagamarra Nelson (1945-2020). ↩

-

Philip Jones, email correspondence with the author, 29 October 2020. ↩

-

Its curator showed me through the unlit museum during the Yuendumu Sports Weekend, August 1978. I recall the ground mosaics, although the murals were not evident in the low light. ↩

-

The museum has recently been renovated and the murals restored under the auspices of Warlukurlangu Artists, the Yuendumu based art centre. Importantly, the screens separating the wings from the central space have been removed to enable both the murals and three newly constructed ground mosaics to be viewed simultaneously. Philip Jones, email correspondence with the author, 29 October 2020. Cf. Finnane, “Beginnings of contemporary Western Desert art,” 2015. ↩

-

Kaapa was born at the Emu Dreaming site at Altjiri, on the songline of the “left-footed” emu depicted in one of the murals in the Yuendumu Men’s Museum. Johnson, Lives of the Papunya Tula Artists, 2008, 17. Darby Jampijinpa and Kaapa were classificatory brothers and shared custodianship of Emu and Water Dreamings. ↩

-

Scholes, “Unmasking the myth,” 2017, 130. ↩

-

Kimber, “Lot 28 (Wild Orange Body Painting, 1971),” in Fine Early Aboriginal & Oceanic Art, Sydney. Sunday 29 August 2010 (Toorak: Mossgreen Auctions, 2010), 32. ↩

-

Philip Jones, email correspondence with the author, 29 October 2020. ↩

-

Title of a song by Kev Carmody and Paul Kelly, written 1991, released 1993. ↩

-

Bardon and Bardon, Papunya, 2004, 12–13. ↩

-

Bardon and Bardon, Papunya, 2004, 14. ↩

-

Wallankarri was Kutungula (policeman/caretaker) responsible to ensure that designs for a particular site are correctly painted and that appropriate protocols observed. ↩

-

This may have been their first meeting as Bardon writes, “A new man became known to me Kaapa Tjampitjinpa (sic).” Bardon, Aboriginal Art of the Western Desert, 1979, 14. ↩

-

Bardon and Bardon, Papunya, 2004, 16. ↩

-

Papunya and the nearby hill, Warumpi, are related sites of major importance, so much so that locals used to refer to the community as Warumpi. ↩

-

See Kaapa Tjampitjinpa, Winparrku Serpents, 1974, Art Gallery Western Australia, in which the artist employs a realistic representation of a serpent to show Yarrapiri’s travels from Winparrku to Ngama. ↩

-

See Philip Batty, “The Tywerrenge as an Artefact of Rule: The (post) Colonial Life of a Secret/Sacred Aboriginal Object,” History and Anthropology, 25, no. 2 (2014): 296-311; Jones, “Objects of Mystery and Concealment: A History of Tjurunga Collecting.” In Politics of the Secret (Oceania Monographs 45), edited by Christopher Anderson, 67–96. Sydney: University of Sydney, 1995, 67–95. ↩

-

Luke Scholes interviewed Fred Friis in preparation for the MAGNT exhibition Tjungunutju. Email communication, with the author, 14 January 2019. ↩

-

See Charles Mountford, “Aboriginal Crayon Drawings Relating to Totemic Places Belonging to the Northern Aranda Tribe of Central Australia.” Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of South Australia, Issue LXI (1937): 84–95. ↩

-

Bardon and Bardon, Papunya, 2004, 17. ↩

-

Bardon and Bardon, 2004, 16. ↩

-

Tim Bonyhady, The Art Master,” Australian Book Review, no. 268 (February 2005): 18–19. ↩

-

Bardon and Bardon, Papunya, 2004, 17. ↩

-

Bardon and Bardon, 2004, 17. ↩

-

Bardon and Bardon, 2004, 17. ↩

-

The second version also included realistically depicted birds (associated with the Honey Ant Dreaming at Papunya). See Fig. Version 2, Bardon and Bardon, 2004, p. 18. ↩

-

‘Western Desert painting’ is something of a misnomer as Papunya is in Central Australia, not the Western Desert, Bardon and Bardon, 2004, p. 16. ↩

-

Bardon and Bardon, Papunya, 2004, 17. ↩

-

See for example Carter, “Introduction: The Interpretation of Dreams,” in Papunya: a place made after the story: the beginnings of the Western Desert painting movement, edited by Geoffrey Bardon and James Bardon (Carlton: Miegunyah Press, 2004), XIV; Grishin, Australian Art, 2013, 445; McLean, “The Gift that Time Gave: Myth and History in the Western Desert Painting Movement,” in The Cambridge Companion to Australian Art, edited by Jaynie Anderson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 183. ↩

-

Vivien Johnson, The Streets of Papunya, 2015, 65. ↩

-

Johnson, Once Upon a Time in Papunya, 2010, 11–43. ↩

-

Johnson, 2010, 11–37. ↩

-

Scholes, “Unmasking the myth,” 2017, 133. ↩

-

Scholes, 2017, 134. ↩

-

Scholes, 2017, 136. ↩

-

Bardon cited in Scholes, 2017, 136. ↩

-

Bonyhady, “the Art Master,” 2005, 18–19. ↩

-

According to the blog, Code Switch, colour film was built for white people, and as a consequence reducing definition in those with darker skin. See “Code Switch: Light And Dark: The Racial Biases That Remain In Photography,” NPR.org. 16 April 2014, [https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2014/04/16/303721251/light-and-dark-the-racial-biases-that-remain-in-photography]{.ul}; “Colour film was built for white people. Here’s what it did to dark skin.” Vox, 16 September 2015,

[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d16LNHIEJzs]{.ul}. Accessed 21 November 2020. ↩

-

Scholes, “Unmasking the myth,” 2017, 160–161. ↩

-

Marcia Langton, “Homeland: sacred visions and the settler state.” Artlink, 20, no. 1 (2000): 11. ↩

-

McLean, “The Gift that Time Gave,” 2011, 192. ↩

-

This process and key protagonists are discussed in detail in the author’s PhD dissertation, Kean, Dot, Circle, and Frame, 2020. ↩

-

Johnson, The Streets of Papunya, 2015, 16. ↩

-

Comparable imagery had been used in a variety of religious and secular settings. For a comprehensive study of those modalities at Yuendumu, see Munn, Walbiri Iconography: Graphic Representation and Cultural Symbolism in a Central Australian Society. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1973. ↩

-

Bardon and Bardon, Papunya, 2004, 17; Kean, Dot, Circle and Frame, 2020, 115–174. ↩

-

Nosepeg Tjupurrula, who was one of the muralists, was a formidable intercultural politician, actor with several movie credits. He was one of the most important ceremonial figures in the Western Desert. Johnston, Lives of the Papunya Tula Artists, 2008, 69–70. Bill Stockman had a long career in political fields. Kean, 2011, “Nosepeg Tjupurrula, 150–151. ↩

-

Mick Wallankarri had a long history as an agent of change in the greater Papunya region. Kean, “Mick Wallankarri,” 2011, 96–97. ↩

-

Scholes, “Unmasking the myth,” 2017. ↩

-

Bardon and Bardon, Papunya, 2004, 16. ↩

-

The William Sandy painting is not the first mural to expound the “two-way” education system on this wall; an earlier collaborative mural is described by Johnson, 2015, The Streets of Papunya, 66. ↩

-

Stockman and Phillipus in discussion with author, Papunya February 2019. ↩

-

Since first commencing research for this essay, several locations within the community have been nominated for the National Heritage List. Those sites include, the original two-story Papunya School building on which the murals were painted, the school darkroom which houses the Papunya Luritja Collection archive of the Papunya Literature Production Centre and the Old Town Hall where men painted sacred images on board from November 1971 until late 1973. ↩

-

Long Jack Phillipus died on the 23^rd^ of August 2020 and is currently respectfully referred to as Kumantjayi. Phillipus cited in Luke Scholes, “Long Jack Phillipus Tjakamarra,” in Tjukurrtjanu: Origins of Western Desert Art, exh. cat., edited by Judith Ryan and Philip Batty (Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria), 2011, 90-91. ↩

-

See for instance Sasha Grishin, Australian Art: A history (Carlton: The Miegunyah Press & Melbourne University Publishing, 2013), 445–450. ↩

John Kean was Art Advisor at Papunya Tula Artists Pty Ltd, (1977–79) inaugural Exhibition Coordinator at Tandanya: the National Aboriginal Cultural Institute (1989–92), Exhibition Coordinator at Fremantle Arts Centre (1993–96), Producer with Museum Victoria (1996–2010). He recently completed a PhD in Art History at the University of Melbourne, focusing on four founding Papunya Tula artists. John has published extensively on Indigenous art and the representation of nature in Australian museums.

Bibliography

- Alkalimat, Abdul et al. Wall of Respect: Public Art and Black Liberation in 1960s Chicago. Evanston Il: Northwestern University Press, 2017.

- Bardon, Geoffrey. Papunya Tula: Art of the Western Desert. Ringwood: McPhee Gribble, 1991.

- Bardon, Geoffrey. Aboriginal Art of the Western Desert. Adelaide: Rigby, 1979.

- Bardon, Geoffrey, and James Bardon, Papunya: a place made after the story : the beginnings of the Western Desert painting movement. Carlton: Miegunyah Press, 2004.

- Batty, Philip. “The Tywerrenge as an Artefact of Rule: The (post) Colonial Life of a Secret/Sacred Aboriginal Object.” History and Anthropology, 25, no. 2 (2014): 296–311.

- Beasely, Margo. Wharfies: a history of the Waterside Workers’ Federation of Australia. Rushcutters Bay, N.S.W.: Halstead Press in association with the Australian National Maritime Museum, 1996.

- Bonyhady, Tim. “The Art Master.” Australian Book Review, no. 268 (February 2005): 18–19.

- Carter, Paul. “Introduction: The Interpretation of Dreams.” In Papunya: a place made after the story: the beginnings of the Western Desert painting movement, edited by Geoffrey Bardon and James Bardon, pp.xiv–xxi. Carlton: Miegunyah Press, 2004.

- Finnane, Kieran. “Beginnings of contemporary Western Desert art.” Alice Springs News, 31 July 2015. https://alicespringsnews.com.au/2015/07/31/yuendumu-writes-new-chapter-on-the-beginnings-of-contemporary-western-desert-art/

- Grishin, Sasha. Australian Art: A history. Carlton: The Miegunyah Press (Melbourne University Publishing), 2013.

- Hansen, K.C., and L. E. Hansen. Pintupi/Luritja Dictionary. Third Edition. Alice Springs: Institute for Aboriginal Development, 1992.

- Heaney, Seamus. “Squarings XLVIII,”.” In New Selected Poems, 1988–20013, 60, London, Faber and Faber, 2014.

- Johnson, Vivien. The Streets of Papunya: The Re-Invention of Papunya Painting. Randwick, N.S.W.: NewSouth Publishing, 2015.

- Johnson, Vivien. Once Upon a Time in Papunya. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2010.

- Johnson, Vivien. Lives of the Papunya Tula Artists. Alice Springs: IAD Press, 2008.

- Jones, Philip. “Objects of Mystery and Concealment: A History of Tjurunga Collecting.” In Politics of the Secret (Oceania Monographs 45), edited by Christopher Anderson, 67–96. Sydney: University of Sydney, 1995.

- Kean, John. Dot, Circle and Frame: how Kaapa Tjampitjinpa, Tim Leura, Clifford Possum and Johnny Warangula created Papunya Tula art, Doctoral Thesis, University of Melbourne, 2020.

- [http://minerva-access.unimelb.edu.au/handle/11343/242476]{.ul}.

- Kean, John. “Framing Papunya painting: form, style and representation, 1971–72.” In Tjunguṉutja: from having come together, edited by Luke Scholes, 173–94. Darwin: Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, 2017.

- Kean, John. Kaapa Tjampitjinpa, Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri, iIn Tjukurrtjanu: Origins of Western Desert Art, exh. cat., edited by Judith Ryan and Philip Batty, 104–260. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2011, 17-20, 44-46 (respectively).

- Kimber, Richard G. “Nosepeg Tjupurrula.” In Tjukurrtjanu: Origins of Western Desert Art, exh. cat., edited by Judith Ryan and Philip Batty, 280–82. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2011.

- Kimber, Richard G. “Lot 28 (Wild Orange Body Painting, 1971).” In Fine Early Aboriginal & Oceanic Art, Sydney. Sunday 29 August 2010, 32. Toorak: Mossgreen Auctions, 2010.

- Kimber, Richard G. “Papunya — the dialogue of the country.” In Wildbird Dreaming: Aboriginal Art from the Central Deserts of Australia, 39–77. Melbourne: Greenhouse, 1988.

- Kimber, Richard G. “Mosaics you can move.” In Hemisphere, 21, no. 1 (1977): 2–7; 29–30.

- Langton, Marcia. “Homeland: sacred visions and the settler state.” Artlink, 20, no. 1 (2000): 11–6.

- Lowenfeld, Viktor. The nature of creative activity: experimental and comparative studies of visual and non-visual sources of drawing, painting, and sculpture by means of the artistic products of weak sighted and blind subjects and of the art of different epochs and cultures. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1939.

- Maughan, Janet, et al., Dot and Circle: A Retrospective Survey of the Aboriginal Acrylic Paintings of Central Australia, exh. cat. Melbourne: Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, 1986.

- Mclean, Ian. “The Gift that Time Gave: Myth and History in the Western Desert Painting Movement.” In The Cambridge Companion to Australian Art, edited by Jaynie Anderson, 180–92. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Mountford, Charles. “Aboriginal Crayon Drawings Relating to Totemic Places Belonging to the Northern Aranda Tribe of Central Australia.” Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of South Australia, Issue LXI (1937): 84–95.

- Munn, Nancy D. Walbiri Iconography: Graphic Representation and Cultural Symbolism in a Central Australian Society. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1973.

- Penny, D.H., et al. Papunya: History and Future Prospects, a report prepared for the Ministers for Aboriginal Affairs and Education. Unpublished Manuscript, 1977.

- Rowse Tim, ed. Contesting Assimilation. Perth: API Network, 2005.

- Scholes, Luke. “Unmasking the myth: the emergence of Papunya painting.” In Tjunguṉutja: from having come together, edited by Luke Scholes, 127–61. Darwin: Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, 2017.

- Scholes, Luke. “Long Jack Phillipus Tjakamarra.” In Tjukurrtjanu: Origins of Western Desert Art, exh. cat., edited by Judith Ryan and Philip Batty, 92–3. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2011.

- Smith, Mike. The Archaeology of Australia’s Deserts. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Sutton, Peter. The Politics of Suffering: Indigenous Australia and the End of the Liberal Consensus. Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne University Press, 2009.

WEBSITES

- Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Defining Moments: Australian Exhibition Histories 1968–1999, https://acca.melbourne/series/defining-moments/.

- “Code Switch: Light And Dark: The Racial Biases That Remain In Photography.” NPR.org. 16 April 2014. https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2014/04/16/303721251/light-and-dark-the-racial-biases-that-remain-in-photography

- “Colour film was built for white people. Here’s what it did to dark skin.” Vox, 19 September 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d16LNHIEJzs.

- “Warumungu Honey Ant Totem designs.” Spencer & Gillen: A journey through Aboriginal Australia. http://spencerandgillen.net/objects/4fac6981023fd704f475b5d0.

FILM

- Strehlow, Theodor George Henry. Yerrampe, and Possum at Wolatjatara Ceremonial camp, digital copy of film, Alice Springs: Strehlow Research Centre, 1955.