No Stickers on Hard-Hats, No Flags on Cranes How the Federal Building Code Highlights the Repressive Tendencies of Power

On 6 November 2019, two Australian Building and Construction Commission (ABCC) inspectors arrived at a multi-million dollar construction site in Melbourne.1 Given the complex processes involved in building a project such as this, the presence of a government regulatory agency is not surprising; work health and safety standards, building quality, structural soundness, and wage theft are ongoing issues within the industry, and compliance checks would be expected. Yet the two inspectors were not there for those reasons. Rather, “the purpose of the visit was to identify and take photographs of any union mottos, logos or indicia observed on the cranes, walls of the walkway and the walls of the lunch rooms as a continuation of an audit to assess compliance with the Code for the Tendering and Performance of Building Work 2016 (the Code).”2 As the two inspectors walked the site, they took multiple and comprehensive photographs of any posters, flags or stickers on workers’ hard hats that had the logo of the Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union (CFMMEU) displayed.3 This included posters that informed workers of “Wage Increases through the EBA [Enterprise Bargaining Agreement], Site Allowances, the CFMMEU RDO [Rostered Day Off] calendar, CFMMEU Fundraisers [and] OHS [Occupational Health and Safety] Alerts.”4 Other notable posters depicted “a chook and a message relating to not working in the rain [that] has the CFMEU Victoria logo on the bottom of it (the chook poster)”; “a poster with CFMEU across the top and a young man dressed in construction gear, wearing a T-shirt with the words “Construction Union” along with a black hard hat with a logo of the CFMMEU”; “a poster bearing logos of the CFMMEU attached to the wall of the lunchroom outlining the benefits of the association.”5

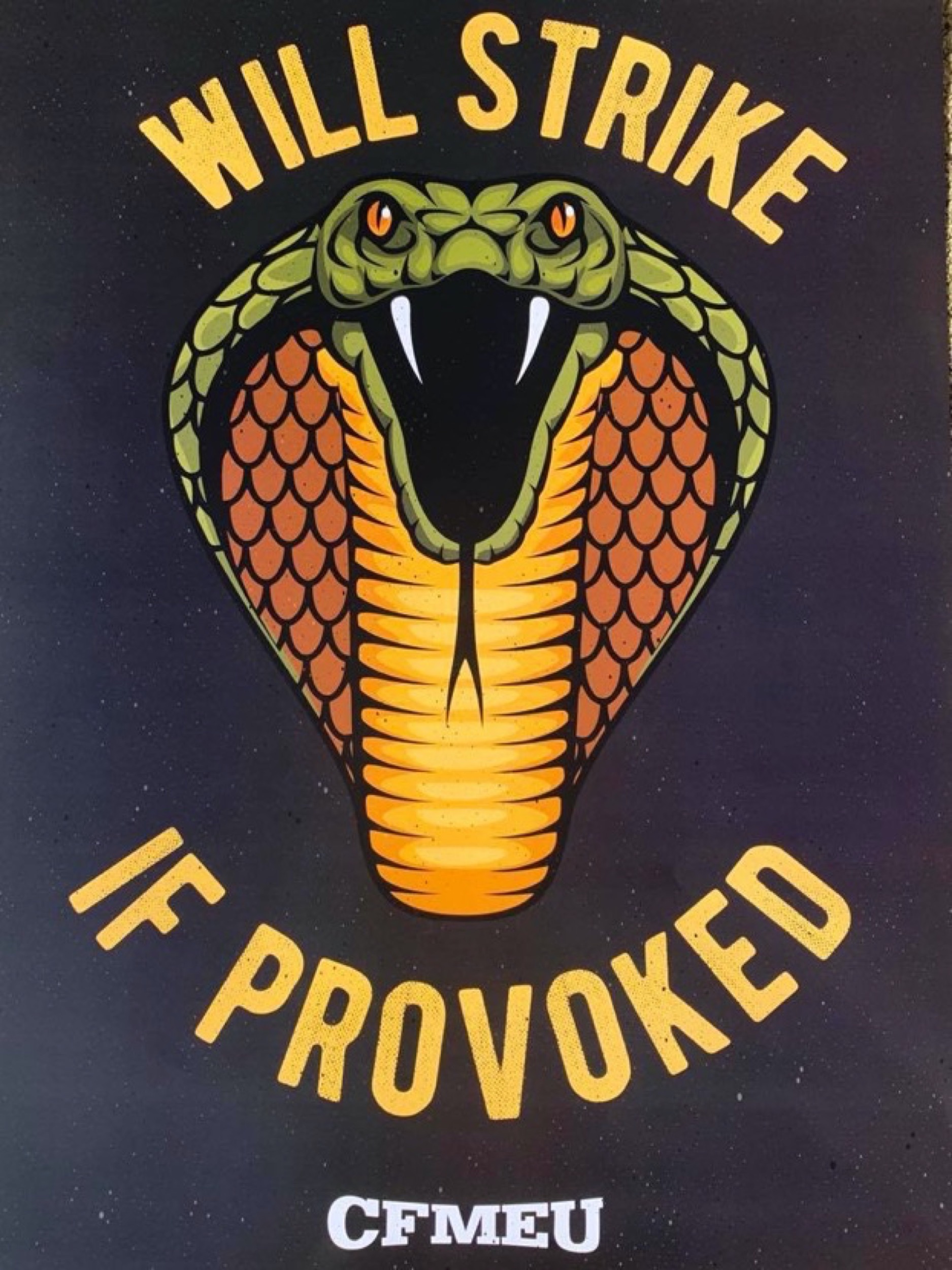

This was not the first visit by ABCC inspectors to this particular Melbourne site. Photos from previous visits note: “A stuffed animal can be seen hanging from the power cord to the air conditioning unit. The stuffed animal is wearing a black hard hat that is affixed with multiple stickers with logos, mottos or indicia of the CFMMEU” and “An esky is resting on a box beneath the stuffed animal. The esky has a number of union stickers attached to it. The owner of the esky is not known.”6 The inspectors collected a catalogue of images of CFMMEU stickers found on workers’ helmets, toolboxes and lunchboxes including the phrases “100% Union”; “There is Power in a Union”; “United we Bargain, Divided we Beg”; “Keep the dirty rats out”; “Danger, Militant Unionist”; “Dare to Struggle, Dare to Win”; “Grub Busters” and “If Provoked, Will Strike.”7 The inspectors reported that “during the site walk, Inspectors observed the crane crew chanting for the CFMMEU. A member of the crane crew was seen to be wearing [a Union Sticker covered hat].”8

These interactions, and dozens of others like them, were meticulously documented by the inspectors as potential breaches of the Code. The documentation includes hundreds of photos, ranging from individual construction workers wearing hard hats covered in union stickers, to the Eureka Flag, flying high above the site, atop a crane.9 This matter is currently before the Federal Court of Australia, as the builder, multinational corporation Lendlease, has sought judicial review on the validity of aspects of the Code for the Tendering and Performance of Building Work 2016 (Code) that prohibit union insignia. For this multi-million-dollar project, high-powered legal teams pour over hundreds-of-pages of documents, filled with photos of union flags, posters, and stickers.

Iconomy and Idolatry

When the state seeks to control images through legal mechanisms, it reveals two things. First, that there is an instinct for overreach that is inherent to power, even in a liberal democracy. Second, that the visual is a powerful tool of expression and identity, and therefore a principal target of the legal and political apparatus. “Religion and law have a long history of policing images,” argue Costas Douzinas and Lynda Nead, “coupled with an economy of permitted images or icons, an iconomy, and a criminology of dangerous, fallen or graven images, and idolatry.”10 Interactions between certain images and powerful institutions like the Australian Federal Government’s ABCC and the Code are discussed in this paper.11 Because, while it is ostensibly about improving productivity by regulating the procurement of building work by government, the Code also seeks to regulate trade union stickers, flags and other images.12

While art can be a culturally loaded and narrow term, it can also be understood not just as images in a gallery but also as images used in everyday life. Understood in this way, union stickers are clearly a form of art. Art as a visual phenomenon is an immensely powerful form of expression. According to seventeenth-century emblematist Matthaeus Merian, “men believe much more in the eyes than the ears … it is through the eyes that the great truths are imprinted upon the human soul.”13 More than a form of communication, visual images can be icons imbued with power and belief, as frequent episodes of iconoclasm since time immemorial attest. Critical legal scholar, Peter Goodrich, has more recently suggested that images are “expressly a manner of inserting something, a law, a norm, a moral, into the interior of the subject.”14 In this sense, images are norm-creating and norm-challenging—a projection of human imagination and culture. Art therefore has a political presence. Opposing ideologies take shape through aesthetic means. Writing on contemporary art, Benjamin Buchloh has described its current meaning in ever more bolder terms, as “a tool of ideological control and cultural legitimation.”15 At the same time, images can convey a counter-narrative that both provokes the ideological policing of the state and resists it. Images both elicit state power and repudiate it.

For this reason, those in power have always sought to control and sway the iconography of images. This has taken many forms, from outright desecration—iconoclasm—to the methods under consideration here: legal restriction. Even the law itself requires visual media; aesthetics is a necessary component of its institutions. Images give law legitimacy, “the appearance of official authority, and draw on an aesthetic of harmony and order.”16 Thus the aesthetic of the law is a source of its influence, and the law in turn shapes the visibility of images. Douzinas and Nead describe the law as a “deeply aesthetic practice … Law’s force depends partly on the inscription on the soul of a regime of images …”17 The creation of an interconnected regime of imagery is thus a form of cultural legitimation. The dominant political ideology is less concerned with restricting a certain image or artwork from being viewed as creating an aesthetic regime that represents the totality of who or what is seen. French philosopher Jacques Rancière, for example, describes an “aesthetic regime of politics [that] is strictly identical with the regime of democracy, the regime based on the assembly of artisans, inviolable written laws, and the theatre as institution.”18 Thus, the dominant political ideology in Australia is, in part, an aesthetic one, and images that challenge this are subject to legal control.

The Neo in liberalism

While even the liberal state is tempted to overreach, the ideology of neoliberalism that has been ascendant since the 1980s shows no qualms about doing so:

By creating a hegemonic discourse of “neoliberal reason” in which all human and social interactions must be understood exclusively in terms of individual and economic goals, the basis of social and collective action is removed. The language of “society” becomes unthinkable, “common good” and “non-economic value” oxymorons.19

While diminishing its interaction with economic regulation through privatisation and budget cuts, the neoliberal state at the same time increasingly seeks to regulate trade union activity. On the one hand, the state has reduced the capacity of unions to be seen by limiting their interaction with members,20 or their ability to act within the state apparatus.21 On the other hand, union interactions with the state has increased through a surge in regulatory surveillance. Understood in this way, neoliberalism is reduceable to a “legal ideology that also cast an affirmative preference for hierarchy and inequality as non-intervention.”22 Wendy Brown has described the impact this has had on collective power:

When these kinds of assaults on collective consciousness and action are combined with neoliberalism’s displacement of democratic values in ordinary political discourse … the result is not simply the erosion of popular power, but its elimination from a democratic political imaginary. It is in that imaginary that democracy becomes delinked from organised popular power and that these forms of identity and the political energy they represent disappear …23

The more militant the union, the more such assaults occur. In Australia, the CFMMEU, perhaps the nation’s most militant union, has been subjected to an expansive and coercive regulatory system generally not deployed against other unions. As a prominent source of industrial power, the CFMMEU has been a target of neoliberal regulatory attention. While other construction unions such as the Australian Manufacturing Workers’ Union (AMWU), the Australian Workers Union (AWU), and the Communications Electrical and Plumbing Union (CEPU) are covered by the Code, the ABCC prioritises enforcement against the CFMMEU specifically. Neoliberal governments from both sides of Australian politics have targeted construction unions for this reason. A predecessor to the CFMMEU, the Builders Labourers Federation (BLF)—famous for instigating the Green Bans in Sydney during the 1970s—was deregistered by the Labor Party’s Hawke Government, in large part for its refusal to accept pay cuts prescribed by the Prices and Incomes Accord between the Federal Labor Government and the Australian Council of Trade Unions.24 As a prelude to the expansion of regulatory power under the Code, the threat of loss of government work was used by both Federal and State Labor governments to prevent construction companies bargaining with the BLF after it was deregistered.25 The Victorian Building Code introduced by the Cain Government went so far as to exclude companies from Government work that allowed BLF members to work on their sites.26

Inevitably, therefore, the exercise of neoliberal regulation has a visual dimension that crosses both Labor and Liberal party lines. By prohibiting the use of visual marks of trade unionism, the state limits collective identity and unified voices, increasing atomisation until all alternatives to the neoliberal model of hyper-individual economic rationalism become quite literally unimaginable.27

The Iconoclasm of the Building Code

A procurement code may not be the most obvious example of this phenomenon, but its absurdity demonstrates precisely the extent to which the state’s war against union power has been carried on through iconoclasm, a war against images. Under the Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Act (the Act), the Minister may issue by “legislative instrument” a building code in relation to procurement and work health and safety on Australian building sites.28 Decisions made under the Code are not subject to judicial review under the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act (ADJR Act) or administratively reviewable by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal, resulting in limited access to review of decisions.29 The Federal Building Code outlines the “expected standards of conduct for all building industry participants that seek to be, or are, involved in Commonwealth funded building work.”30 And this is the kicker: building companies that do not comply with the apparently voluntary code are not able to tender for government projects. The Code’s stated purpose is to “encourage the development of safe, healthy, fair, lawful and productive building sites.”31 Ostensibly concerned with freedom of association, the Code states:

building association logos, mottos or indicia are not applied to clothing, property or equipment supplied by, or for which provision is made by, the employer or any other conduct which implies that membership of a building association is not a personal choice for any employee.

This is an inversion of freedom of association as it is usually understood in international law. For example, the International Labour Organisation’s Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention, 1948, confers on workers a positive right to join trade unions:

Workers’ … organisations shall have the right to draw up their constitutions and rules, to elect their representatives in full freedom, to organise their administration and activities and to formulate their programmes …The public authorities shall refrain from any interference which would restrict this right or impede the lawful exercise thereof.32

Australian domestic labour law has historically recognised visual expression as essential to the fulfilment of those rights.33 As long ago as 1918, the High Court of Australia declared, “The direct object of the claim to wear a badge as a mark of unionism is to place the workers in a stronger position relatively to their employers with respect to the conditions of their employment.”34 Yet under the Building Code, the freedom not to join a trade union entitles the state, in the exercise of its freedom, to minimise and exclude alternate organising structures and specifically to forestall any visual expression of those structures. The logos or indicia prohibited by the Code include the symbol of a trade union, “the iconic symbol of the five white stars and white cross on the Eureka Stockade flag,” signs or stickers that are placed on clothing, cranes, helmets, mobile phones, tools and more.35

The Code implicitly recognises the importance of these images, noting the “iconic” nature of the Eureka flag, for example. Despite years of repression, these symbols remain prevalent on construction sites where union membership is relatively highly concentrated. Flying flags on cranes and wearing stickers on safety helmets is a common expression of support for trade unionism and solidarity. They are the visual manifestation of an ideological position. While the stickers often are accompanied by text, such as “100% Union,” “No Free-Loading,” or “No Ticket, No Start,” the images can pack an immediate and visceral punch—a striking cobra, a rat, a raised fist, or the skull-and-cross-bones.

Enforcement of the Code has led to the dismissal of workers who have refused to remove stickers from their helmets. In 2016, construction company Laing O’Rourke sacked three union members and gave written warnings to 130 others for refusing to comply with a direction to remove their stickers.36 Laing O’Rourke undertook this action at the direction of the ABCC following a Fair Work Building Commission audit of the site that found “serious breaches”—meaning workers wearing sticker-covered hard hats.37

Flags depicting the Eureka symbol have also been targeted. In another case, Watpac Construction Pty Ltd v CFMEU, Commissioner Riordan dismissed a claim that the flag conveyed that union membership was not voluntary.38 Riordan noted that the Eureka flag was a widely used political symbol in Australia and that its presence did not represent compulsory unionism. Despite this finding, the ABCC has continued to enforce strict compliance with the iconophobia of the Code.

The Code’s subjectivity is an essential aspect of its function; it is reliant on the arbitrary enforcement of the ABCC. The stickers and posters themselves are not inherently compliant or non-compliant. Rather, the distinction between compliance and non-compliance is ever flexible and evolving, to suit the capricious regulatory system. As such, what is a code compliant image varies. One example sees the ABCC currently pursuing Lendlease for failing to prevent the CFMMEU from displaying the Eureka flag on its sites (described at the beginning of this essay), but across other construction sites Eureka flags remain undisturbed.39 Similarly, union stickers and posters are subject to arbitrary enforcement. Indeed, the ABCC’s efforts to prevent any and all forms of union presence on construction sites frequently brings it into conflict with the traditional supporters of the liberal state: the bosses. Through the Code, the ABCC forces building companies to become belligerents in a proxy war between the state and the union. These differences in enforcement are not the result of differing appreciation of the aesthetics of particular union stickers but the alternating utility of companies’ opposition to union insignia for the ABCC’s agenda. As the CEO of the construction company Watpac asked after facing possible sanctions by the ABCC for the volume of CFMEU calendars and safety posters on sites: “The prevalence of a rostered day off calendar or a CFMEU safety sign—does that imply the site is promoting anything other than free choice? What if you have ten of them?”40 Another builder, Hutchinson, was suspended from tendering for government work for three months in 2017 for allowing a “no ticket, no start” union poster on its sites.41 Not even the wishes of capital, or equal application of the law, will stand between the neoliberal state and its need for control over the means of (visual) production.

The Rise of the Regulatory State and the Diminishing Power of Trade Unions

For most of the twentieth century, Australia’s industrial relations system revolved around the Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1904 (Cth). Under this system, 90 per cent of workers were covered by an industrial award bargained for by a union, and between 42 and 62 per cent of workers were union members.42 Unions were active participants in the public sphere. The system was based on the concept of “comparative wage justice,” where the “strong protected the weak” as the industrial strength of highly unionised industries was the anchor to less unionised industries.43 Highly unionised industries were the tide that floated all boats. This resulted in Australia’s relatively egalitarian wage structure. Trade unions were a dominant presence in the social fabric. They were deeply ingrained in the culture of Australia, their absence unimaginable and essential to the function of Australian Keynesian capitalism.

The importance of the visual dimension of unions’ presence in Australian culture and society was explicitly recognised by the High Court in Australian Tramway Employees Association v Prahran and Malvern Tramway Trust 1918. 44 Industrial rights, the majority found, could not be gained by individuals successfully; collective organisation, including visual expression of that organisation, was necessary.45 Union insignia was protected under the arbitration power of the constitution:

The creation and maintenance of organisations unions are incidental to this power, it seems to follow inevitably that a claim by a member of such an organisation, created and recognised by law for the very purpose of upholding his rights, to evince his membership by wearing a badge of that membership, cannot be foreign to the same power.46

In the 1980s and 1990s, Australia’s industrial framework experienced a paradigm shift that broke with the conceptualisation of labour relations contained in the Conciliation and Arbitration Act.47 The system that institutionalised collective voice was dismantled in favour of one that promoted individualism. Instead, “militant managerialism” came to define industrial relations.48 Far from removing “red-tape,” the reforms initiated under both the Keating and Howard Governments, between 1991 and 2007, shifted many industrial matters into statute as opposed to the award, as awards covered increasingly stripped back “allowable matters.”49 Awards were transformed from the primary mechanism of regulation of the workplace—where “primary wage cases” acted to create industry-wide conditions—into minimum standards decided by the Fair Work Commission that unions and business can make submissions to, as opposed to create through bargaining.50 Government became the enforcer of compliance, and unions’ entry to workplaces was restricted.51 The so-called “deregulation” of the labour market in Australia demonstrates these complexities very clearly. The steady growth of neoliberal re-regulation in recent years has involved unprecedented levels of state intervention—and anti-unionism—”quite at odds with Australia’s past.”52 This is why neo-liberalism has also been called “regulated liberalism,” as the vast regulatory state embed corporate influence rather than control it.53

The Political Power of Aesthetics

The Code confirms the tendency of power to seek control of visual expression. Its purpose, notwithstanding its stated goal of protecting freedom of association, is to diminish and disrupt trade-union activity and expression. Rancière describes how the hegemonic ability of the state to control the visibility of people, communities, or ideas “dooms … the majority of speaking beings to the night of silence.”54 Invisibility removes the possibility of communication—the prohibition of union stickers seeks to prevent collective communication on construction sites. If art, as Rancière points out, is also the “framing of a space of presentation by which the things of art are identified as such,” the environments for such a presentation must also be considered.55 In this way, “art is not defined, art is legitimised.”56 Union insignia is therefore able to be understood as similarly accessible through the regime of visibility: far from being legitimised as art, however, they are delegitimised as a violation of the right to freedom of association. The contrast with the treatment by the law of corporate logos, signs, and images, vigorously protected from any encroachment on their right to be seen and preserved inviolate, is striking. On construction worker’s helmets, the logo of their employer is acceptable imagery under the Code. On the cranes above the site, the construction company’s flags fly undisturbed. On the microcosm of the construction site, the state legitimises imagery that conforms to the neoliberal world view: “the forms of domination … within the very tissue of ordinary sensory experience.”57 As Douzinas has argued, the iconomy is sacred, and idolatry—the countering of image with image, of imaginary by imaginary—is ruthlessly suppressed.

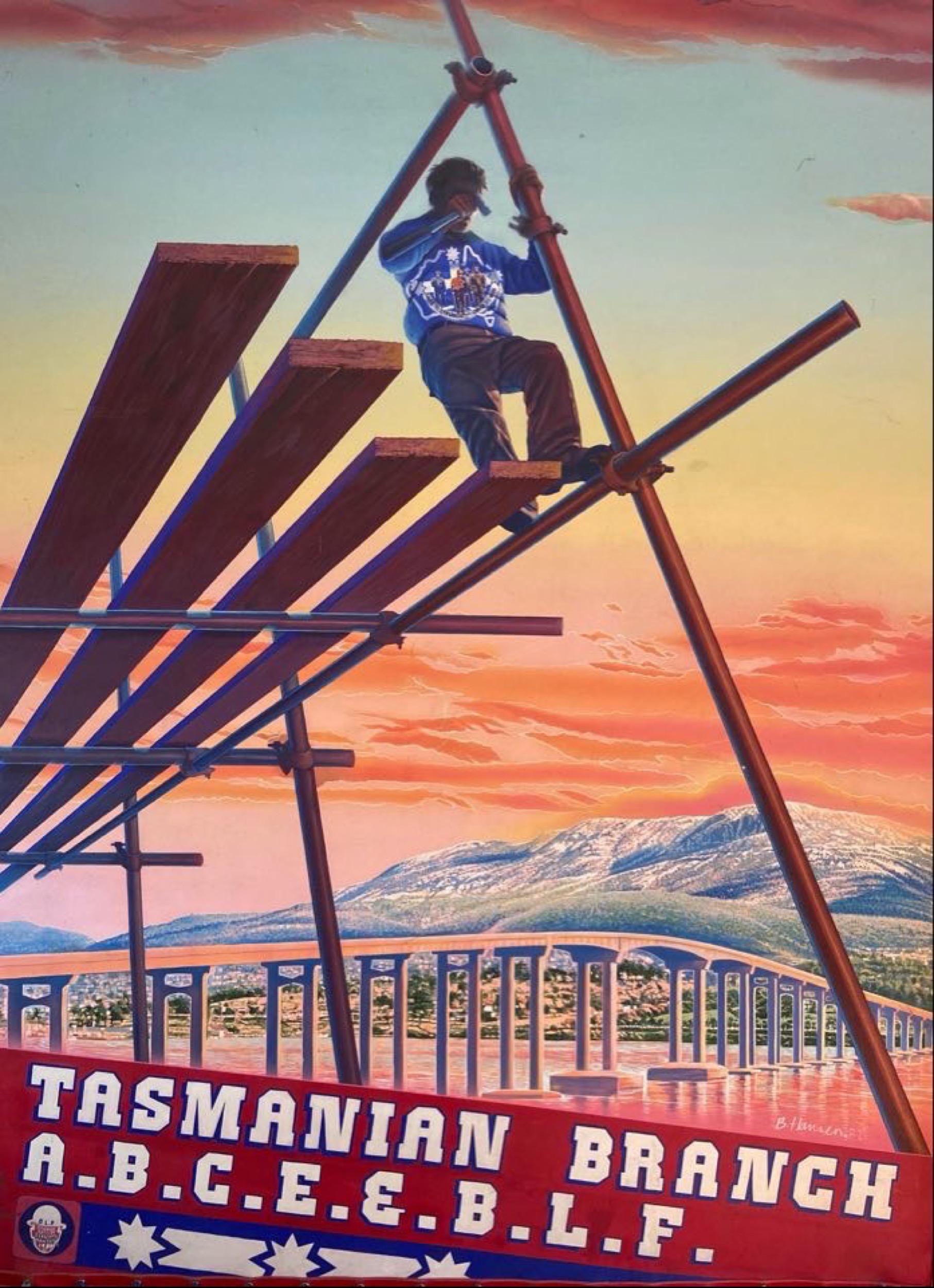

Imagery, in many instances, is more immediately powerful and evocative than speech. The use of stickers by construction unions instantaneously communicates a complex political message through an icon. The union movement has always understood this power. From the beginnings of class-critique and worker consciousness in the nineteenth century, collective struggle has been portrayed through the symbols and iconography of labour. Union ideas have always emphasised the visual, originally out of necessity due to higher levels of illiteracy amongst workers but also in recognition of the intimate relationship between aesthetics and politics. Well aware of the aesthetic dominance of capital, unions sought to create alternate cultural structures: Working Men’s Colleges, labour media, musicals and exhibitions.58 In Australia in the 1930s and 1940s, social realism “sought to depict the struggles of society’s marginalised groups and the injustices of the capitalist system.”59 Artists Noel Counihan, Jack Maughan, and Nutter Buzacott formed the Worker’s Art Club in Melbourne in 1931, producing its own media, artworks, and hosting performances.60 During the early 1980s, the twilight of the conciliation and arbitration system, unions and government created the “Art and Working Life” program (AWL) to create public artworks relevant to working people. Some unions had cultural officers, and some trade halls levied affiliation fees to run arts programs.61 The four major building unions in the early 1990s employed a cultural officer, and their collective agreements required that building projects with a value of over $1 million spent one per cent of their value on commissioned Australian artworks to be displayed in the building.62 Images have long been essential to the collective cultural identity of unionism. Today’s stickers and posters are a direct link to this visual history.

By invoking a visual narrative of solidarity and identity, union stickers and flags operate in the communicative field of art. Douzinas describes the Byzantine use of “aesthetics to create and propagate an all-inclusive perception of the world … the elaborate iconography created a sense of identity … the icon is an aesthetic, moral and political category.”63 But this could also be a description of the trade unions’ efforts to forge, through signs and images, a collective identity of workers. Stickers and posters portray a moral or political choice, a political position to be a member of a trade union. Like the iconography of old, they are designed to elicit an emotional response from the viewer. The rat, or the scab, is a term of derision for a non-union worker; the visual of the rat is a common feature of union iconography. Does the viewer want to “kick the dirty rats out”? Do they want to “bargain united”? Does the image of a raised fist encourage the viewer? Or turn them away? The creation of group identity through images is part of their power. Group identity similarly requires others to not identify with the imagery and so “other” themselves from the group.64

The Eureka flag, flying high above the construction site, is a powerful visual link to a famous historical event and a set of values that are culturally assigned as originating from the Eureka Stockade, an 1854 rebellion of goldminers against the British Crown at Ballarat in the Australian state of Victoria. Irishman Peter Lalor lead the rebelling miners in an oath: “We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other and fight to defend our rights and liberties.”65 The flag was a visual expression of the rebellion and the egalitarian impulses of Australia’s emerging identity. The images are creation stories, self-portraits of the union’s existence. At a less conceptual level, union posters articulate this message. These include posters listing the historic wins of unions, entitlements under the CFMMEU’s enterprise agreements and safety warnings and procedures.

Depoliticization and Delegitimization

Examples of the control of visual and other imagery by the state are numerous; art’s power to produce symbols is evident in it always having been subject to some form of state censorship. Visual iconography is about creating and breaking norms, and, as such, their erasure or silencing is norm creating and breaking too. In silencing the visual expression of union presence in the area, the state seeks to create new norms out of that absence. In attacking a visual culture that exists outside of its ideology, the state disrupts the historical retelling and reimagining of political images. The visual presence of unions exalts their physical presence in the workplace and in public space more generally. So too their visual absence is a repudiation of their demands for political participation. Gabriel Rockhill also describes how the existence of visual signs understood as “non-art,” and as “that which is not permitted to attain the status of art … is an important site of politics.”66 This is because “it reveals, to begin with, the political orientation of the establishment, which seeks to control not only what is produced but also what circulates and is received by the general populace.”67 In Plato’s Republic, the ideal state separates the citizenry into silos; the workman must not participate in politics: “the workman must be a professional at the call of his job; his job will not wait till he has leisure to spare for it.”68

The Code echoes this Platonic thought; the political participation of a construction worker through the wearing of a union sticker is to be discouraged precisely because the worker should not—must not—participate in the body politic while working. Neither Platonic thought nor the liberal state could conceive of the politics of work, or of work, as necessarily political. Thus, construction workers’ political voice is rendered illegitimate. Political discourse is narrowed and confined—it belongs in the halls of parliament or our rapidly shrinking newsrooms but nowhere else. Issues of life and death on a work site, the conflict between the profit margin and safe work conditions, are made invisible to the liberal political project.

Thus, the state aggressively pursues the visual representation of workplace political action because in the state’s world view, it is illegitimate. The “distribution of the sensible” is how Rancière describes this process, as “the system of self-evident facts of sense perception that simultaneously discloses the existence of something in common and the delimitations that define the respective parts and positions within it.”69 Rancière argues that “having a particular “occupation” thereby determines [one’s] ability or inability to take charge of what is common to the community; it defines what is visible or not in a common space, endowed with a common language.”70 In this sense, the construction worker lacks political legitimacy because of the operation of this very process of categorisation, of recognition. In Rancière’s framework, union stickers, as the visual expression of worker politics, are outside the distribution of the sensible and thus outside the “regime aesthetic.”71

The deployment of the liberal category “art” legitimises some visuals—at the expense of their political salience—and reduces the rest to garish noise. In a sense, the contents of the actual images themselves are less important; it is their distribution that upends the dominant social order. But it is their presence that matters, as much as their message. Unionist and artist Ian Burn (1939–1993), who was raised in Geelong, described the importance of images differently to Rancière, focussing rather on “the way that art validates the actions, ideas and values inherent in the forms of organisation and resistance developed by working people in their own interest.”72 Union images are a challenge to the ideological project of the state both in their placement and their expression of a counternarrative that exists despite the tyranny of the aesthetic regime that would exclude their voice. Rancière’s concept of “indisciplinarity” builds on Marx’s critique of the division of labour: “the distribution of territories, which is always a way of deciding who is qualified to speak about what.”73 Democracy is the “poetic assertion of equality by the unaccounted,” the removal of qualification for a voice, or the siloing of aesthetic participation.74

Hence there is a need by the state to limit the presence of stickers, flags, and other emblems. The state categorises these images as non-art, as non-work, and as illegitimate politics. This distribution of the sensible is maintained by the “police,” a wider concept than its legal usage might suggest.75

The police is, in its essence, the law which, though generally implicit, defines the part or lack of part of the parties involved. But to define that, one must first define the configuration of the sensible in which the various parties are inscribed. The police is thus above all a bodily order that defines the partition between means of doing, means of being and means of saying, which means that certain bodies are assigned, by their very name, to such and such a place, such and such a task; it is an order of the visible and the sayable, which determines that some activities are visible and that some are not, that some speech is heard as discourse while others are heard as noise.76

Rancière’s “police” combine both institutional violence and cultural regulation. The ABCC is a clear example of this institutional control of image legitimacy, literally a system to delegitimise union aesthetics. Rancière charges that contemporary capitalism’s main aim is the erosion of democratic politics in favour of the police. The arbiters of social discourse fail to challenge the reality of the coalescing of power structures; “the antidemocratic discourse of the intellectuals adds the finishing touches to the consensual forgetting of democracy that both state and economic oligarchies strive toward.”77 In an even wider sense, the reader, upon viewing the union iconography in this essay, the crass slogans, the lack of care for social mores of the workplace, is experiencing and participating in this cultural delegitimisation. The very feeling of recoil at the elements of vulgarity is, in Rancière’s thesis, the distribution of the sensible in motion.

The Picture of the Law

In seeking to control union images, the neoliberal state reveals the illiberal underbelly of law and power. The importance of property and capital are central to any discussion of the liberal concept of the rule of law. But images and art can be used to disrupt legal conceptions of property. Another form of visual disruption is graffiti. In a similar sense, graffiti is a constant visual reminder of alternate occupiers of spaces: taggers, excluded by their lack of legal ownership of urban spaces, insisting on remaining visible. Likewise, the union flag above a construction site demands recognition of the workers’ presence in the creation of the building. The law too shows itself in aesthetic terms: the courtroom, the blindfolded figure of justice, the scales. As a concept, it is fetishized as a defining feature of the West and as a key, causal factor in the West’s economic rise, its expansion, its civilisation. The concept of “the West” is drawn from the inclusion and exclusion of select visual narratives. Similarly, the law derives legitimacy from its image—its impartiality, clarity, and its perceived neutrality.78

The Code and its policing bring the reality behind this picture of the law into focus. On 18 September 2018, 66 construction workers refused to return to work on a site in Brisbane, after the removal of CFMMEU flags from the cranes on the site. The 66 workers faced individual fines between $14,000 and $42,000 for their decision.79 This was one of several instances of the ABCC fining individual workers as opposed to the union as an entity or union officials in the first half of 2018. The ideological struggles over union images have significant consequences for workers and their unions. The policing of union images is in stark contrast to the self-image of the law. What is the purpose of this meticulous documenting of the presence of the Eureka flag? In a sense, the Code reveals law’s ideological underbelly. Its prohibition of “phrases that express an organisation’s guiding principle” is indicative of the state’s desire to exercise a monopoly over narratives, creation myths, and images.80 The history of construction unions, the values, struggles and victories that represent this, must be hidden from sight. Douglas-Scott argues:

In this situation, an economic, instrumentalist logic, a creature of capitalism, has tended to dominate and function as a place marker for legitimacy. Law has frequently adopted this logic, as well as its technical reason, its reliance on contract and property (the attributes of commerce) and its belief in the “rational actor” of the law and economics doctrine, and … all of these often come together in that most foundational of legal concepts, the rule of law.81

It is important to note that the Code and the ABCC do not represent an entirely uniform legal position on union images. As with all things, the law can be also present a contradictory construct. At the Fair Work Commission in 2018, Commissioner Riordan rejected the ABCC’s position on union images:

The Code prohibits any conduct whatsoever which would imply that joining a building union is anything but an individual choice, once again re-affirming the freedom of association provisions of the Act. The question to be determined then requires an examination of whether the identified conduct, (in this instance, the flying of the CFMMEU and Eureka flags on the sites’ cranes) implies to an employee working on these Watpac sites that joining the CFMMEU is anything but voluntary.82

The Code and the ABCC are extreme, even within the neoliberal legal landscape of Australia. They are examples of the increasingly tightening grip on dissent that characterises the deeply illiberal heart of the neoliberal system and the use of institutions to erase spaces, real and imaginary, that present any alternative to it. Construction workers find themselves excluded from participating in political and cultural spheres beyond a very narrow definition of their position. They remain simply a steel fixer, a crane driver or a bricklayer, the legitimacy of their voices extending only to the edge of their exact position. Their broader collective voice is being systematically excised by the police, the Code, and the ABCC. Their images and self-expression are being fastidiously removed from the picture of the workplace and the city. Yet they persist. The flag flying high above a construction site confirms a fundamental political desire: to be seen.

-

Lendlease Building Contractors Pty Limited v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner & Anor, 2020 Federal Court, statement of ABCC inspector, November 19, 2019, 19. ↩

-

Lendlease v ABCC, ABCC Compliance Officer, 22. ↩

-

In 2018 the then Construction Forestry Mining and Energy Union (CFMEU) merged with the Maritime Union of Australia (MUA) to form the CFMMEU. This essay will refer to the union as the CFMMEU, unless directly quoting a source prior to the merger. ↩

-

Lendlease v ABCC, 30. ↩

-

Lendlease v ABCC, ABCC Compliance Officer, 34–35, 37 ↩

-

Lendlease v ABCC, ABCC Compliance Officer, 69. ↩

-

Lendlease v ABCC, 69. ↩

-

Lendlease v ABCC, 79. ↩

-

Lendlease v ABCC, 87–88. ↩

-

Costas Douzinas and Lynda Nead, Law and the Image: The Authority Of Art and The Aesthetics Of Law (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 9. ↩

-

In the legislation the Building Code[ ]{dir=”rtl”}is the code of practice referred to in section 34 of the Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Act 2016 (Cth) s 34. ↩

-

Construction Industry Act s13(2)(j). ↩

-

Matthaeus Merian quoted in Peter Goodrich, Legal Emblems and the Art of Law: Obiter Depicta as the Vision of Governance, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), xvii. ↩

-

Goodrich, Legal Emblems, xvii. ↩

-

Benjamin Buchloh, “Conceptual Art 1962–1969: From the Aesthetic of Administration to the Critique of Institutions,” October 55 (Winter 1990): 143. ↩

-

Sionaidh Douglas-Scott, “Law, Justice and the Pervasive Power of the Image,” Journal of Law and Social Research, 2 (2014–2015): 5. ↩

-

Douzinas and Nead, Law and the Image, 9. ↩

-

Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics, trans. Gabriel Rockhill (London: Continuum International Publishing, 2004), 14. ↩

-

Desmond Manderson “Push ‘em all: Corroding the Rule of Law,” Arena 1(2020): 26. ↩

-

Cf. Union right of entry laws that restrict union presence in the workplace in the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth). ↩

-

For example, the end of the system of conciliation and arbitration within Australia (discussed further later in this essay). ↩

-

Sanjukta Paul, “A radical legal ideology nurtured our era of economic inequality,” Aeon, June 19, 2019, https://aeon.co/ideas/a-radical-legal-ideology-nurtured-our-era-of-economic-inequality?utm_source=Aeon. ↩

-

Wendy Brown, Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Zone Books, 2015), 153. ↩

-

Drew Cottle, “Brian Boyd, Inside the BLF: A Union Self-Destructs,” The Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, https://www.labourhistory.org.au/hummer/no-33/blf/. See further: The former Secretary of the ACT Branch of the BLF Peter O’Dea described stated the reason for the deregistration of the union was “Obviously the major contribution was the gains in wages and conditions made by builders’ labourers in the past fifteen years, and more importantly the BLF’s determination to hang on to them in the face of a Labor government and an ACTU committed to an ‘Accord’ which had as its object the reduction in living standards.” ↩

-

Humphrey McQueen, We Built This country: Builders’ Labourers and Their Unions (Adelaide: Ginninderra Press, 2011), 332. ↩

-

Anna Pha, “Report on the Deregistration of the Australian Building and Construction Employees’ and Builders Labourers’ Federation and Related Developments,” Victorian Trades Hall Council (June 1986), 8. See further the history of the deregistration of the BLF in Victorian and Federally by two Labor Governments in chapter eleven of Aidan Moore’s thesis: Aidan Moore. “‘It was all about the working class’: Norm Gallagher, the BLF and the Australian Labor Movement” PhD Diss. (Victoria University, 2013), 247–283. ↩

-

Sheldon Wolin described neoliberalism as tending towards an “inverted totalitarianism,” referring to the dominance of corporate power and the ever-narrowing space for ideological difference: ‘politics that is not political’. Sheldon Wolin, Democracy Incorporated: Managed Democracy and the Spectre of Inverted Totalitarianism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017), xxix. ↩

-

Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Act 2016 (Cth) s 34. ↩

-

Breen Creighton “Government Procurement as a Vehicle for Workplace Relations Reform: The Case of the National Code of Practice for the Construction Industry,” Federal Law Review, 40(2012): 377. Note: The Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) remains an avenue of review. Lendlease Building Contractors Pty Limited v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner & Anor has grounds for review under s39B of the Act. ↩

-

Australian Building and Construction Commission, What is the Code? Australian Building and Construction Commission, accessed August 2, 2020, https://www.abcc.gov.au/building-code/what-code. ↩

-

Building and Construction 2016, pt 2 s 5(a). ↩

-

Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention, 1948, No. 87. ↩

-

The Australian Tramway Employees’ Association v The Prahran And Malvern Tramway Trust (1918) 17 CLR, 680. ↩

-

Tramways, 704. ↩

-

“Freedom of association—logos, mottos and indicia,” Australian Building Construction Commission, accessed March 24, 2020, https://www.abcc.gov.au/resources/fact-sheets/building-code-2016/freedom-association%E2%80%94logos-mottos-and-indicia. ↩

-

Benjamin Gee, “The sticky issue of union logos,” FCB Workplace Law, June 15, 2016, https://www.fcbgroup.com.au/news/the-sticky-issue-of-union-logos/. ↩

-

Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia - Electrical, Energy and Services Division - Queensland Divisional Branch v Laing O’Rourke Construction [2016] FWC 3699 (8 June 2016). ↩

-

“ABCC unmoved on Eureka flag ban despite FWC’s contrary view,” Electrical Trades Union Western Australia, published, June 12, 2018, https://www.etuwa.com.au/post/abcc-unmoved-on-eureka-flag-ban-despite-fwc-s-contrary-view. ↩

-

David Marin-Guzman, “Eureka flag ban faces constitutional challenge,” The Australian Financial Review, March 3, 2020, https://www.afr.com/work-and-careers/workplace/eureka-flag-ban-faces-constitutional-challenge-20200303-p546d6. ↩

-

David Marin-Guzman, “Probuild and Watpac facing bans over CFMEU flags and posters,” The Australian Financial Review, October 9, 2017, https://www.afr.com/policy/economy/probuild-and-watpac-facing-bans-over-cfmeu-flags-and-posters-20171009-gyx1uj. ↩

-

Marin-Guzman, “Probuild Watpac Ban.” ↩

-

“Labour Statistics: Concepts, Sources and Methods, 2013: Industrial Relations,” The Australian Bureau of Statistics, May 7, 2015, https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/6102.0.55.001Chapter232013. ↩

-

Barry Hughes, “Wages of the strong and the weak,” The Journal of Industrial Relations 15 (1973): 1–24. ↩

-

The Australian Tramway Employees’ Association v The Prahran And Malvern Tramway Trust (1918) 17 CLR, 694–695. ↩

-

Tramways, 694. ↩

-

Tramways, 704. ↩

-

The Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1904 (Cth). ↩

-

Chris Briggs and John Buchanan, “Australian Labor Market Deregulation: A Critical Assessment,” Economics, Commerce and Industrial Relations Group, Parliament of Australia, June 6, 2000, https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp9900/2000RP21. ↩

-

Andrew Stewart, Stewart’s Guide to Employment Law (Sydney: Federation Press, 2018), 7, 121. ↩

-

Stewart, Employment Law, 120, 131. ↩

-

Mark Bray and Andrew Stewart, “From the Arbitration System to the Fair Work Act: The Changing Approach in Australia to Voice and Representation at Work,” Adelaide Law Review 34 (2013): 31. ↩

-

Rae Cooper and Bradon Ellem, “The Neoliberal State, Trade Unions and Collective Bargaining in Australia,” British Journal of Industrial Relations 46, no. 3 (September 2008): 532. ↩

-

Susan Watkins, “Shifting Sands,” New Left Review 61 (2010): 12. ↩

-

Matthias Frans André Pauwels, “The spectre of radical aesthetics in the work of Jacques Rancière” (PhD diss., University of Pretoria, 2015), 30. ↩

-

Jacques Rancière, Aesthetics and its Discontents (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2009), 23. ↩

-

Sophia Kosmaoglou, “The Self-Conscious Artist and the Politics of Art: From Institutional Critique to Underground Cinema,” (PhD diss., University of London, 2012), 108. ↩

-

Pauwels, “The Spectre of Radical Aesthetics,” 30. ↩

-

Ian Burn, Art: Critical, Political, ed. Sandy Kirby (Nepean: University of Western Sydney, 1996), 11. ↩

-

“20th-century Australian Art: Surrealist-impulse and social realism,” Art Gallery NSW, accessed June 15, 2020, https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/artsets/2e1xzb. ↩

-

“Workers’ Art Club. (1932–).” Trove, accessed June 15, 2020, https://trove.nla.gov.au/people/1772023?c=. ↩

-

Kathie Muir and Ian Burn, Unions in the Arts (Sydney: Union Media Services, 1992), 4. ↩

-

Muir and Burn, Unions in the Arts, 4. ↩

-

Douzinas, Law and Image, 29. ↩

-

Saul McLeod, “Social Identity Theory,” Simply Psychology, October 24, 2019, https://www.simplypsychology.org/social-identity-theory.html. ↩

-

“The Eureka Stockade,” The National Museum of Australia, accessed August 2, 2020. ↩

-

Gabriel Rockhill, “Is Censorship Proof of Art’s Political Power?,” The Philosophical Salon, June 6,2016, https://thephilosophicalsalon.com/is-censorship-proof-of-arts-political-power/. ↩

-

Rockhill. ↩

-

Plato, The Republic, trans. Desmond Lee (London: Penguin, 2007), 60. ↩

-

Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics, 12. ↩

-

Rancière, 13. ↩

-

Rancière, 23. ↩

-

Ian Burn, “Overseas study in relation to the Art and Working Life Program,” Report to the Community Arts Board of the Australia Council (April 25, 1983), 7–8. ↩

-

Jacques Rancière, “Thinking Between Disciplines: an Aesthetics of Knowledge,” Parrhesia 1 (2006): 3. ↩

-

Iftekhar Kabir, “Politics and The Limits of the Common: Dissensus, Deliberation and Democracy in Rancière and Habermas” (Masters Thesis, Trent University, 2011), 14. ↩

-

Rancière, Politics of Aesthetics, 3. ↩

-

Jacques Rancière cited in Stephen Wright “Behind Police Lines: Art Visible and Invisible,” Art and Research 2 (Summer 2008), accessed August 2, 2020, http://www.artandresearch.org.uk/v2n1/wright.html. ↩

-

Jacques Rancière, The Hatred of Democracy, trans. Steven Corocoran (London: Verso Books, 2014), 92. ↩

-

Douglas-Scott, Power of the Image, 9. ↩

-

David Marin-Guzman “Commission Pursues Workers for Striking over CFMEU Flags,” The Australian Financial Review, July 21, 2019, https://www.afr.com/work-and-careers/workplace/commission-pursues-workers-for-striking-over-cfmeu-flags-20190719-p528sp. ↩

-

“Freedom of association—Logos, Mottos and Indicia,” Australian Building and Construction Commission, accessed August 2, 2020, https://www.abcc.gov.au/resources/fact-sheets/building-code-2016/freedom-association—logos-mottos-and-indicia. ↩

-

Douglas-Scott, Power of the Image, 17. ↩

-

Commissioner Riordan, “s739 Application to Deal with a Dispute Watpac v CFMEU,” Fair Work Commission, May 30, 2018, https://cdn.workplaceexpress.com.au/files/2018/Eureka%20recommendation.pdf. ↩

Agatha Court is an undergraduate student at the Australian National University in her final year of a Bachelor of Laws (Honours). She is interested in the role of Trade Unions in Australia and the current legal system’s impact on unions. She is currently an organiser for the Community and Public Sector Union in Canberra.

Bibliography

- “ABCC Unmoved on Eureka Flag Ban Despite FWC’s Contrary View,” Electrical Trades Union Western Australia, published June 12, 2018. Accessed August 2, 2020. https://www.etuwa.com.au/post/abcc-unmoved-on-eureka-flag-ban-despite-fwc-s-contrary-view.

- Art Gallery of NSW. “20th-Century Australian Art: Surrealist-Impulse and Social Realism.” Art Gallery NSW. Accessed June 15, 2020. https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/artsets/2e1xzb.

- Australian Building and Construction Commission. “Freedom of Association—Logos, Mottos and Indicia,” Australian Building Construction Commission. Accessed March 24, 2020. https://www.abcc.gov.au/resources/fact-sheets/building-code-2016/freedom-association%E2%80%94logos-mottos-and-indicia.

- Australian Building and Construction Commission. “What Is the Code?” Australian Building and Construction Commission. Accessed August 2, 2020. https://www.abcc.gov.au/building-code/what-code.

- Australian Council of Trade Unions and Community Arts Board of the Australia Council. Art & Working Life—Cultural Activities in the Australian trade union movement. Melbourne (1983). Accessed August 2, 2020. https://ro.uow.edu.au/hcp/4

- Benjamin, Walter. Selected Writings: Volume 4. Translated by Edmund Jephcott and others. University of Harvard Press, 2003.

- Bray, Mark, and Andrew Stewart. “From the Arbitration System to the Fair Work Act: The Changing Approach in Australia to Voice and Representation at Work.” Adelaide Law Review 34 (2013): 21–41.

- Bottici, Chiara. “Imaginal Politics.” Thesis Eleven 106, no. 1 (August 2011): 56–72.

- Briggs, Chris, and John Buchanan. “Labor Market Deregulation: A Critical Assessment.” Economics, Commerce and Industrial Relations Group8, Parliament of Australia, Research Paper (June 2000).

- Brown, Wendy. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Zone Books, 2015.

- Buchloh, Benjamin. “Conceptual Art 1962–1969: From the Aesthetic of Administration to the Critique of Institutions.” October 55 (Winter 1990): 105–143.

- Burn, Ian. “Overseas Study in Relation to the Art and Working Life Program.” Report to the Community Arts Board of the Australia Council (April 25, 1983).

- Burn, Ian. Art: Critical, Political. Edited by Sandy Kirby. Sydney: University of Western Sydney, 1996.

- Ciampi, Annalisa. “The Power of Images through Law, Art and History.” Pólemos 13, no. 1: 1–5.

- Collier, Stephen J. “Topologies of Power: Foucault’s Analysis of Political Government beyond “Governmentality.”“ Theory, Culture & Society 26, no. 6 (November 2009): 78–108.

- Commissioner Riordan. “s739 Application to Deal with a Dispute Watpac v CFMEU.” Fair Work Commission. May 30, 2018. https://cdn.workplaceexpress.com.au/files/2018/Eureka%20recommendation.pdf

- Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Act 2016 (Cth).

- Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia—Electrical, Energy and Services Division—Queensland Divisional Branch v Laing O’Rourke Construction [2016] FWC 3699 (8 June 2016).

- Cooper, Rae, and Bradon Ellem. “The Neoliberal State, Trade Unions and Collective Bargaining in Australia.” British Journal of Industrial Relations 46, no. 3 (September 2008): 532–554.

- Cottle, Drew. “Brian Boyd, Inside the BLF: A Union Self-Destructs.” The Australian Society for the Study of Labour History. Accessed 14 August 2020. https://www.labourhistory.org.au/hummer/no-33/blf/.

- Creighton, Breen. “Government Procurement as a Vehicle for Workplace Relations Reform: The Case of the National Code of Practice for the Construction Industry.” Federal Law Review, 40 (2012): 349–384.

- Danchev, Alex and Debbie Lisle. “Art, Politics, Purpose.” Review of International Studies 35, No. 4 (2009): 775–779.

- Dasgupta, Sudeep. “Art Is Going Elsewhere: And Politics Has To Catch It: An Interview With Jacques Rancière.” Krisis 9, no. 1 (2008): 70–76.

- Douglas-Scott, Sionaidh. “Law, Justice and the Pervasive Power of the Image.” Journal of Law and Social Research 2 (2014–2015): 1–19.

- Douzinas, Costas, and Lynda Nead. Law and the Image: The Authority of Art and The Aesthetics Of Law. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

- Fair Work Commission. Commissioner Riordan, “s739 application To Deal with a Dispute Watpac v CFMEU.” Fair Work Commission. Accessed May 30, 2018. https://cdn.workplaceexpress.com.au/files/2018/Eureka%20recommendation.pdf.

- Forsyth, Anthony. “Law, Politics and Ideology: The Regulatory Response to Trade Union Corruption in Australia.” UNSW Law Journal, Volume 40, no. 4 (2017): 1336–1365.

- Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention, 1948, No. 87.

- Gee, Benjamin. “The Sticky Issue of Union Logos.” FCB Workplace Law (June 15, 2016). Accessed August 2, 2020. https://www.fcbgroup.com.au/news/the-sticky-issue-of-union-logos/.

- Goodrich, Peter. Legal Emblems and the Art of Law: Obiter Depicta as the Vision of Governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 2013.

- Hughes, Barry. “Wages of the Strong and the Weak.” The Journal of Industrial Relations 15 (1973): 1–24.

- Kabir, Iftekhar. Politics and The Limits of the Common: Dissensus, Deliberation and Democracy in Ranciere and Habermas. Masters Thesis. Trent University, 2011.

- Kosmaoglou, Sophia. The Self-Conscious Artist and The Politics of Art: From Institutional Critique to Underground Cinema. PhD thesis. University of London, 2012.

- Kirby, Sandy. “Art and Working Life in the Mid-90s: a critical assessment.” Art: Critical, Political Forum (August 1986): 2.

- Kosmaoglou, Sophia. The Self-Conscious Artist and the Politics of Art: From Institutional Critique to Underground Cinema. PhD thesis. University of London, 2012.

- “Labour Statistics: Concepts, Sources and Methods, 2013: Industrial Relations.” The Australian Bureau of Statistics published May 7, 2015.

- Lendlease Building Contractors Pty Limited v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner & Anor, 2020 Federal Court, statement of Robert Dalton, ABCC inspector, November 19, 2019.

- Manderson, Desmond. “Push ‘em all: Corroding the Rule of Law.” Arena 1(2020): 24–36.

- Marin-Guzman, David. “Commission Pursues Workers for Striking over CFMEU Flags,” The Australian Financial Review, July 21, 2019. https://www.afr.com/work-and-careers/workplace/commission-pursues-workers-for-striking-over-cfmeu-flags-20190719-p528sp.

- Marin-Guzman, David. “Eureka Flag Ban Faces Constitutional Challenge.” The Australian Financial Review, March 3, 2020. https://www.afr.com/work-and-careers/workplace/eureka-flag-ban-faces-constitutional-challenge-20200303-p546d6.

- Marin-Guzman, David. “Probuild and Watpac Facing Bans over CFMEU Flags and Posters.” The Australian Financial Review, October 9, 2017. https://www.afr.com/policy/economy/probuild-and-watpac-facing-bans-over-cfmeu-flags-and-posters-20171009-gyx1uj.

- McLeod, Saul, “Social Identity Theory.” Simply Psychology. Accessed 17 August 2020. https://www.simplypsychology.org/social-identity-theory.html

- McQueen, Humphrey. We built this country: Builders’ Labourers and their Unions. Adelaide: Ginninderra Press, 2011.

- Miles, Richard. “Indisciplinarity as Social Form: Challenging the Distribution of the Sensible in the Visual Arts,” Message (2016): 35–55.

- Moore, Aidan, “‘It was all about the Working Class’: Norm Gallagher, the BLF and the Australian Labor Movement.” PhD Thesis. Victoria University, 2013.

- Muir, Kathie, and Ian Burn. Unions in the Arts. Sydney: Union Media Services, 1992.

- National Museum of Australia, The Eureka Stockade. The National Museum of Australia. Accessed August 2, 2020. https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/eureka-stockade

- Paul, Sanjukta. “A Radical Legal Ideology Nurtured our Era of Economic Inequality.” Aeon. Accessed June 2, 2020. https://aeon.co/ideas/a-radical-legal-ideology-nurtured-our-era-of-economic-inequality?utm_source=Aeon.

- Pauwels, Matthias Frans André. “The Spectre of Radical Aesthetics in the Work of Jacques Rancière.” PhD thesis. University of Pretoria, 2015.

- Pha, Anna. “Report on the Deregistration of the Australian Building and Construction Employees” and Builders Labourers’ Federation and Related Developments.” Victorian Trades Hall Council (June 1986).

- Phillips, John W.P. “Art, Politics and Philosophy: Alain Badiou and Jacques Rancière.” Theory, Culture & Society 27, no. 4 (July 2010): 146–60.

- Plato. The Republic. Translated by Desmond Lee. London: Penguin, 2007.

- Rancière, Jacques. Aesthetics and its Discontents. Translated by Steven Corcoran. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2009.

- Rancière, Jacques. La Mésentente. Paris: Galilée, 1995.

- Rancière, Jacques. The Hatred of Democracy. Translated by Steven Corcoran. London: Verso Books, 2014.

- Rancière, Jacques. The Politics of Aesthetics. Translated by Gabriel Rockhill. London: Continuum International Publishing, 2004.

- Rancière, Jacques. “Thinking Between Disciplines: An Aesthetics of Knowledge,” Parrhesia 1 (2006): 1–12.

- Rockhill, Gabriel. “Is Censorship Proof of Art’s Political Power?” The Philosophical Salon, June 6, 2016. https://thephilosophicalsalon.com/is-censorship-proof-of-arts-political-power/.

- Sayer, John. “Art and Politics, Dissent and Repression: The Masses Magazine versus the Government, 1917–1918.” American Journal of Legal History 32, no. 1 (January 1988): 42–78

- Stewart, Andrew. Stewart’s Guide to Employment Law. Sydney: Federation Press, 2018.

- The Australian Tramway Employees’ Association v The Prahran and Malvern Tramway Trust (1913) 17 CLR 680.

- Tomc, Sandra. “A Form of Life in which Art is not Art: Life in the Iron Mills and the Artist as Worker in the Nineteenth-Century United States.” American Literature 89, no. 3 (2017): 497–527.

- Vihalem, Margus. “Everyday Aesthetics and Jacques Rancière: Reconfiguring the Common Field of Aesthetics and Politics.” Journal of Aesthetics & Culture 10, no. 1 (2018): 1–10.

- Wright, Stephen. “Behind Police Lines: Art Visible and Invisible.” Art and Research, no. 2 (summer 2008). http://www.artandresearch.org.uk/v2n1/wright.html.

- Watkins, Susan, “Shifting Sands,” New Left Review 61 (January–February 2010): 5–27.

- Wolin, Sheldon, Democracy Incorporated: Managed Democracy and the Spectre of Inverted Totalitarianism. Princeton University Press, 2017.

- “Workers’ Art Club. (1932-).” Trove. Accessed June 15, 2020. https://trove.nla.gov.au/people/1772023?c=.

- Wright, Stephen. “Behind Police Lines: Art Visible and Invisible.” Art and Research 2 (Summer 2008). http://www.artandresearch.org.uk/v2n1/wright.html.