Editors’ Introduction

The movement formally known as “law and literature” has evolved from a relatively benign interest, almost a hobby really, into a dynamic interdisciplinary project which draws on humanities scholarship—not just in literary studies but in and about art, music, history, and philosophy—to think about legal issues in the contemporary world.1 These cultural perspectives offer novel insights into our legal ideas and legal history, sometimes more or less directly, and sometimes via a sideways glimpse. Aesthetic curiosity has been accompanied by a strong interest in theoretical frameworks, also drawn from the humanities, whether in terms of literary theory, social theory, critical theory, post-colonial studies, or continental philosophy. Much more recently, and with a truly propulsive energy, this broad focus has found new life and energy in what is often called “the visual turn.” After an initial foray,2 a flurry of recent activity has seen the methods and theories of art history, criticism, and theory drawn on to understand, critique, and engage with law.

Political discourse, as Chiara Bottici pointedly argues,3 is not particularly imaginative nowadays, and it’s certainly not imaginary. But it is fought out increasingly in the realm of, and through, visual media. The same could be said of legal discourse. Accounting for law’s material and visual manifestations, its living presence, invites the kind of rich case studies around the relationship between legal and visual discourses at the heart of this collection.

The so-called visual turn reflects broader developments across the humanities. Judith Butler,4 Giorgio Agamben,5 Jacques Rancière,6 Mieke Bal,7 and many others insist that aesthetic forms, disciplines, and genres are central to political, cultural, and social discourse. Whether we are talking about political liberalisms, economic rationalisms, or legal theories of social justice and human rights narrowly conceived, orthodox conceptual epistemologies seem incapable of grasping the discursive crisis of our current predicament. Still less do they seem capable of finding new ways of imagining and instigating the future. For that, we need new vocabularies of law and social justice, and new communicative forms. That is precisely where the connection between law and aesthetics is both illuminating and promising.

There is nothing remotely new about any of this. If we accept that visual studies concerns the relationship between images and the discourses they realise, legitimate, or set in motion, then this collection’s claim for their importance to law is, if not as old as the hills, then at least as old as Hammurabi’s Code.

That great basalt plinth marked, in the detail and specificity of the written laws it set down, an important milestone in law’s textual presence. But equally important is the image of legality that crowns the stele and materialises out of its black-headed stone (fig. 1). Here we see the shining Babylonian sun god, the god of justice Shamash, flames sprouting from his shoulders, giving Hammurabi a ring and a staff as signs of his authority. The connection is made explicit in the Prologue:

Then Anu and Bel delighted the flesh of mankind by calling me, the renowned prince, the god-fearing Hammurabi, to establish justice in the earth, to destroy the base and the wicked, and to hold back the strong from oppressing the feeble: to shine like the sun-god upon the black-headed men and to illuminate the land.

Clearly, then, law is making a claim to authority not just through the medium of images but about images, about the legal system’s relationship to light and vision, the coming together of its power to illuminate and the illumination of its power. The language of light is not just a metaphor for the law; it is its origin and its justification.

Indeed, this law of and in the image, is a great deal more venerable than Hammurabi. On the opposite wall in the Louvre where it now stands, there is an almost identical image dated hundreds, maybe a thousand years earlier. The temporal distance is staggering. What we might naively have supposed to be an image of Hammurabi was nothing of the sort. By his time the picture of the king and the god was already an ancient, conventional, even ritual evocation of a familiar trope. It probably seemed old-fashioned even then. And perhaps that was the point. The iconography of the image was an enduring stamp of legitimation and authority; Hammurabi’s insight lay in appropriating the magic of the image of authority in order to justify specific legal obligations. An eye for an eye.

The emergence of visual studies of law reflects an intensified interest in the ancient compact between aesthetics, politics, and law. It also echoes a long tradition of using visual materials to understand legal ideas—think of Michel Foucault’s use of the Panopticon;8 Ernst Kantorowicz’s focus on the origin of modern sovereignty in “the king’s two bodies”;9 Louis Marin’s book on the Sun King as the creature and creation of his own portrait (fig. 2).10 Do not think of the representation of power, Marin instructs us; think instead of the power of representation, of the power that representation makes possible and to which it is indispensable.

Consider our most famous constitutional artwork (fig. 3). Perhaps the legitimacy and authority of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 (UK) seemed self-evident in 1901, when we still spoke of “the mother of Parliaments” and “the mother country.” Australia’s Constitution was enacted in London according to old traditions, themselves largely “invisible.” The Big Picture (1903), by Tom Roberts, Australia’s most famous and biggest turn of the century painting, depicts the ceremonial opening of the first Parliament of Australia in Melbourne that year. The future King George V reads the official proclamation. His authority is burnished by the pageantry of the official party. An over-sized crown looms over them like the trappings of some modern Leviathan. To this day, Roberts’ painting does not belong to the Australian people. It may be on display in Parliament House, but it still remains part of the British Royal Family’s private collection. But even in 1901, legitimacy was not simply conferred by the Imperial origins of Australia’s constitutional arrangements. The painting stages a dramatic contrast between dark and light. The official guests are still in mourning for the old Queen, who had died just a few months previous. They are all dressed in black. The choir, on the other hand, is all in white, bathed in a glorious light that pours in from the window high above. They stand for the Australian people, for the future, not the past. And the proclamation being read by the Duke catches a shaft of the same light. It is the light of God, the guarantor of all promises and contracts. It binds the official document to the people, who are on the one hand subject to Parliament’s laws and on the other the very body to whom those laws must themselves answer. The multitude of spectators becomes a people in that moment. Intriguingly, Tom Roberts did not sign The Big Picture; we may rightly say that its true signatories are the nation and the divine. Thus the artist creates here a vision of the Constitution which exceeds the words of the text and founds the Australian legal order on something more enduring and transcendent, which binds its people together. Indeed, the town planners of the nation’s capital, Canberra, unconsciously—or was it consciously—recognised this by placing the National Gallery and the High Court beside each other, connected by a bridge, each of the same brutalist architecture: law, art, and nation entwined and imprinted on the soft curvilinear forms of the lake and surrounding hills. What remains utterly remarkable about this juxtaposition is their subtle difference. The gallery welcomes visitors while the court stays aloof. The brutalist forms of the National Gallery have blended into the bush landscape that envelops it, permeating and softening its edges, while next door at the High Court the same style and forms have not. Australian art has achieved a reconciliation with its place; Australian law, it seems, hasn’t.

It would be a mistake to think of scholarly work on the nexus of art and law as the discovery of some hitherto hidden trace of legal ideology in the interstices of art. While art historians and critics are yet to return the favour with the same conscious attention, the nexus of art and law is an unconscious assumption of artworld discourse, whether it be in the analysis of church and state patronage or avant-garde transgressions. This nexus has always been implicit if not explicit, which is to say ancestral, to art. Originally the law was in the land and the heavens, manifest in the footprint of ancestral creator lawmakers (the Indigenous concept of Country is a law-full or ancestral-full land) and also in kin relations and clan designs. Art and law are the twin doubles of the transcendental blinding light of Shamash or the more ancient Mesopotamian Utu.

If the modern world is characterised by the separation of disciplines into autonomous sovereign fields, the continuing force of iconoclasm reminds us how fragile the separation between art and law is. Artists have long understood this. The work of Gordon Bennett comes immediately to mind, an artist for whom the imposition of colonial law and British sovereignty was precisely a matter of images shaping the Australian subconscious or social imaginary. Almost any work by Bennett makes the point, from his retelling of Captain Cook taking possession of Australia, Possession Island (1991), to his painting of the mutual hegemony of Western art, space, and law, in the aptly legally titled Terra Nullius (1993).11 More recently, Julie Gough (e.g., Hunting Grounds, 2017), for example, presses on the visual fantasies of Australian colonial law and the legal fantasies of colonial Australian art, like a finger worrying an open wound. Questions of legal power, legal history, and legal justice are absolutely central to the work of many major Indigenous artists; likewise, questions about law and justice for Indigenous peoples are being confronted more bravely, more directly, and more coherently in the arts than in the discourse of politics or law itself.12

In compiling this issue of Index, we imagined a disciplinary field that doesn’t yet exist in any institutional sense but which we believed to be out there, long at work, largely unknown even to some of its participants. To give this field a semblance of form, submissions needed to tick a number of boxes: scholars who range from emerging to experienced, and whose essays crossed enough topics and approaches to be rich, interesting, and informative. We received contributions from scholars working in many different ways across the apparently irreconcilable disciplines of law and art history. Their work makes the case for their indispensable relation with coruscating eloquence, convincing even a casual reader that they have much to talk about and to learn from each other.

We are delighted with what eventuated: ten essays that relate art and law through the lenses of power, ideology, and critique across a wide range of areas and subjects from the early modern to the contemporary. The approaches are equally wide-ranging, including philosophical, semiological, sociological, historical, and iconographical. However, what each writer shares is more important than these differences: a commitment to interrogating art as an image that creates knowledge, and so requires a careful consideration of the limits of what it can know—or of what it conceals in its revealing. This scrutiny of the image is, in each essay, accompanied by an acute awareness that it is not simply an illustration but a double, and that its power as an image lies in its structure of the double, which is the structure of language.

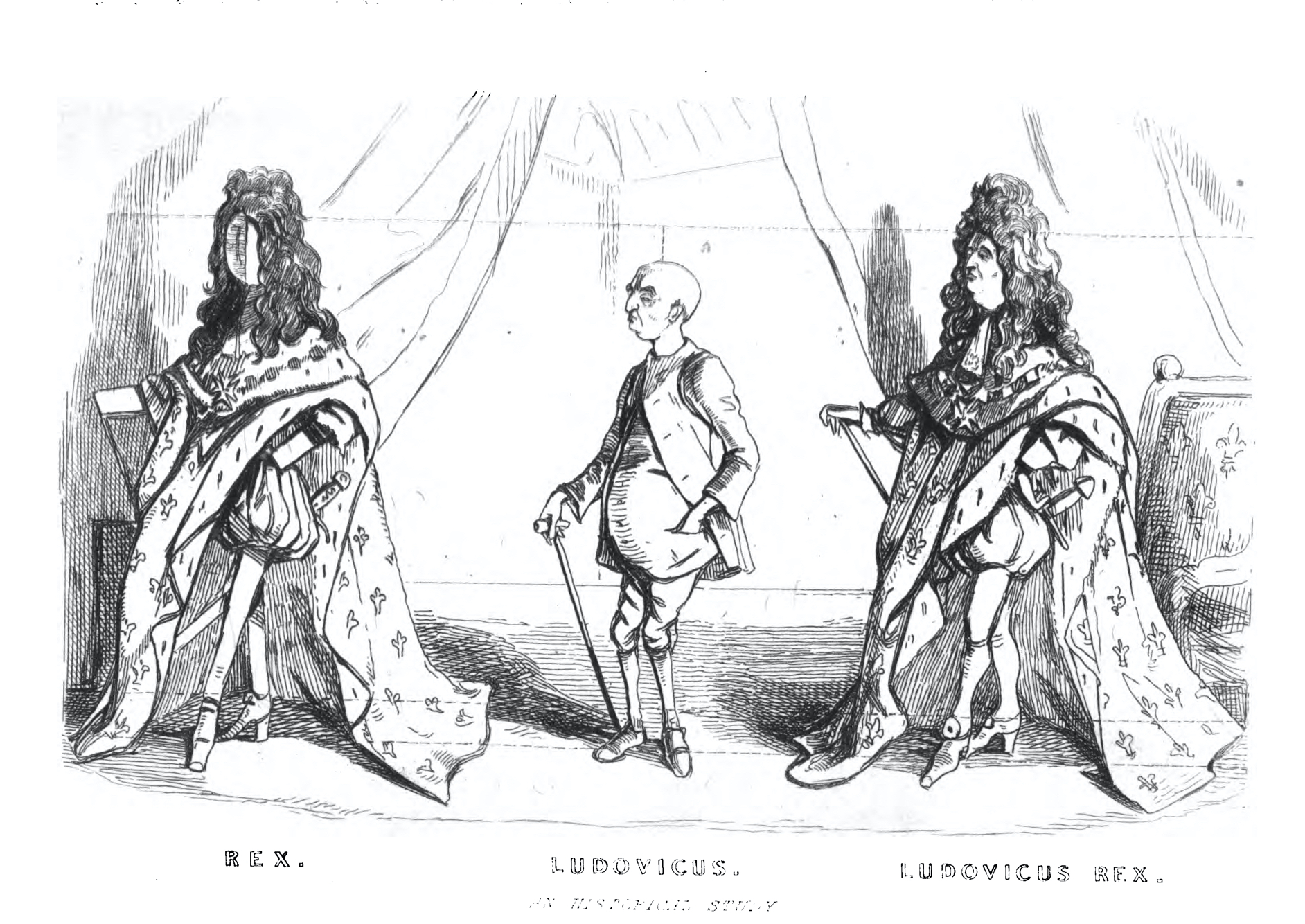

For many of the essays, it was a short step to the law being equally a doubled figure which, ghost-like, is more powerful in its apparent absence, in its silence and invisibility, than in its presence. Hence, there is a strong agreement in these essays of an inherent complicity between the image and the law—of the image as law and law as image, and the law in the image (a definition of aesthetics) and the image in the law (a definition of power). This sense of law and image being two sides of the same coin provided the necessary leverage for many of the authors’ insights. It lent a philosophical edge to many of the essays and suggested that the law is not so much an emperor without clothes but—as in Thackeray’s engraving What Makes the King?—an excess of robes without an emperor (fig. 4).

Organising ten essays that represent new work in a new field proved more challenging than selecting them, a problem with which many a curator could surely sympathise. Part 1, “Lawscapes,” features essays by Desmond Manderson, Helen Hughes, David Caudill, and Shane Chalmers. The term itself we took from Hughes’s essay, which in turn gestures to Andreas Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos and Nicole Graham.13 Like them, we mean a materially and historically grounded space of law, which these essays approach through the analysis of characteristic visual signifiers. In stark contrast, the essays by Clare Fuery-Jones, Keith Broadfoot, and James Parker in Part 2 of this collection take a metaphysical turn. “Lacunae” suggests that the power of law rests not so much in what it says but what it does not say, what it prohibits from being said, what remains unspoken or invisible. Through this aesthetic of silence and the unseen, veils, and shadows, our authors illuminate or discover law’s ineffable force and the force of its ineffability. With a nod to Erwin Panofsky,14 Part 3, “Icons,” features essays which are political rather than philosophical in tone, and contemporary rather than historical in perspective. What after all is an icon but the most political and ideological—the most strictly speaking lawful—form of the image? An icon is a political sign that seeks to position itself above the play of interpretation or contention or dissent. An icon is an image that, as Hans Belting argues, strives to achieve not likeness but presence.15 The icon does not aspire to represent the law (as in Part 1) or its absence (Part 2), but to be the law. It is a level of ideological control of the image that these essays seek to unveil and more importantly to challenge.

For all of the writers here assembled, the questions this interdisciplinary field raises are not merely curious or interesting or intriguing or amusing. This was brought home to us in the short life of this editorial project. As we face the unprecedented crises of the twenty-first century—more to the point, the unprecedented crises of 2020—we need more than business as usual. What we need are new ways of thinking about the world that connect political and social critique to visions of the future. In making those connections, cultural resources and aesthetic forms will be crucial—crucial to how they are, following Elaine Scarry, “made up,” but equally crucial to how they are “made real”: given an emotional existence that breathes life and meaning into them.16

Facing an existential challenge to our species’ stewardship of the planet, we urgently need an outpouring of critical insight into the origin and contours of our current predicament. It will take a fresh commitment to normative ideals related to justice, equality, and sustainability. And it will take imagination—narrative vision, aesthetic force—if these critiques and commitments are to be carried into a public sphere that has been systematically unravelled by neoliberalism and yet17—to quote Carol Gilligan—must be, can only be, “mended with its own thread.”18 Is anything other than law and art up to the task?

-

Austin Sarat, Matthew Andrson, and Cathrine Frank, eds., Law and the Humanities: An Introduction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010). ↩

-

Costas Douzinas and Lynda Nead, eds., Law and the Image: The Authority of Art and the Aesthetics of Law (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1999). ↩

-

Chiara Bottici, Imaginal Politics: Images Beyond Imagination and the Imaginary (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014). ↩

-

Judith Butler, Frames of War (New York: Verso, 2009). ↩

-

Giorgio Agamben, Stasis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015). ↩

-

Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, trans. Gabriel Rockhill (London: Continuum, 2004); Jacques Rancière, The Future of the Image, trans. Gregory Elliott (London: Verso, 2009); Jacques Rancière, Aisthesis: Scenes from the Aesthetic Regime of Art, trans. Zakir Paul (London: Verso, 2013). ↩

-

Mieke Bal, Quoting Caravaggio: Contemporary Art, Preposterous History (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2001). ↩

-

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (New York: Vintage, 1977). ↩

-

Ernst Kantorowicz, The King’s Two Bodies (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1957). ↩

-

Louis Marin, Portrait of the King, trans. Martha House (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988). ↩

-

See Manderson, Danse Macabre, 162–6, 189–90. ↩

-

See Jennifer Biddle, Remote Avant Garde (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016). ↩

-

Andreas Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos, Spatial Justice: Body, Lawscape, Atmosphere (London: Routledge, 2014); Nicole Graham, Lawscape: Property, Environment, Law (London: Routledge, 2010). ↩

-

Erwin Panofsky, Studies in Iconology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939). ↩

-

Hans Belting, Likeness and Presence (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994). ↩

-

Elaine Scarry, “The Made Up and the Made Real,” Yale Journal of Criticism 5 (1992): 239. ↩

-

Wendy Brown, Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015). ↩

-

Carol Gilligan, In a Different Voice (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982), 31. ↩

Desmond Manderson directs the Centre for Law, Arts and the Humanities at Australian National University. His most recent book is Danse Macabre: Temporalities of Law in the Visual Arts.

Ian McLean is Hugh Ramsay Chair of Australian Art History at the University of Melbourne.

Bibliography

- Agamben, Giorgio. Statis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Bal, Mieke. Quoting Caravaggio: Contemporary Art, Preposterous History. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2001.

- Belting, Hans. Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image Before the Era of Art. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

- Biddle, Jennifer. Remote Avant Garde. Durham: Duke University Press, 2016.

- Bottici, Chiara. Imaginal Politics. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014.

- Brown, Wendy. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015.

- Butler, Judith. Frames of War. New York: Verso, 2009.

- Douzinas, Costas, and Lynda Nead, eds. Law and the Image: The Authority of Art and the Aesthetics of Law. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1999.

- Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage, 1977.

- Gilligan, Carol. In a Different Voice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982.

- Goodrich, Peter. Legal Emblems and the Art of Law. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Goodrich, Peter, and Valerie Hayaert, eds. Genealogies of Legal Vision. London: Routledge, 2015.

- Graham, Nicole. Lawscape: Property, Environment, Law. London: Routledge, 2010.

- Kantorowicz, Ernst. The King’s Two Bodies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1957.

- Manderson, Desmond. Danse Macabre: Temporalities of Law in the Visual Arts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Manderson, Desmond, ed. Law and the Visual. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018.

- Marin, Louis. Portrait of the King. Translated by Martha House. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988.

- Panofsky, Erwin. Studies in Iconology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939.

- Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos, Andreas. Spatial Justice: Body, Lawscape, Atmosphere. London: Routledge, 2014.

- Rancière, Jacques. Aisthesis: Scenes from the Aesthetic Regime of Art. Translated by Zakir Paul. London: Verso, 2013.

- Rancière, Jacques. The Future of the Image. Translated by Gregory Elliott. London: Verso, 2009.

- Rancière, Jacques. The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible. Translated by Gabriel Rockhill. London: Continuum, 2004.

- Resnik, Judith, and Dennis Curtis. Representing Justice. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011.

- Sarat, Austin, Matthew Andrson, and Cathrine Frank, eds. Law and the Humanities: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Scarry, Elaine. “The Made Up and the Made Real.” Yale Journal of Criticism 5 (1992): 239.