Multiple Selves Nikki S. Lee’s Projects

Between 1997 and 2001, New York-based South Korean conceptual photographer Nikki S. Lee created a series of performative photographic works she titled Projects. To make these works, Lee infiltrated a range of social and cultural groups, including drag queens, exotic dancers, yuppies, Latinos, black hip-hoppers, lesbians, senior citizens, neo-swing dancers, Japanese youth, skateboarders, Ohio trailer-park dwellers, Asian tourists and Korean schoolgirls. At the beginning of each project, Lee identified a particular group of people that she wished to integrate herself into and studied their stereotypical semiotic codes and lifestyles. Lee dramatically altered her appearance through a blend of clothing, makeup, diet, hair extensions, use of hair dye and tanning salons. After transforming herself, in her own words, into someone who looks like “eighty percent of any person from whichever group,” Lee approached each chosen community with a point-and-shoot camera and announced her artistic intention of becoming a member for a short period of time.1 She adopted their gestures, behaviours and mannerisms and joined in their everyday activities. In some cases, Lee also learnt new skills, such as skateboarding and dancing, from other group members or personal trainers. As a record of her temporary membership, Lee asked a friend or a passer-by to take snapshot photographs of herself with other group members in a series of deliberately chosen milieus where diverse yet collective activities occur. When exhibited, viewers can easily pick out the artist, who is simultaneously a part of and apart from each featured group.

Lee’s Projects are endowed with multiple functions, as she uses photography—an art medium, which is associated with both the promise and criticism of truth and authenticity, to document her artistic constitution and exploration of identities that are nonetheless artificial and staged. The indexical nature of photography enables Lee to present her time-stamped snapshots as “fake” documentaries of various simulated personas she tries on. Following the vernacular ritual of snapshot photography—posing and smiling to mark memorable moments of holidays, parties, family reunions and other public events, Lee’s works fabricate scenarios of “social belonging” in the disguise of other group members with whom she hangs out for a period of weeks or months. Made during the first few years after her move to New York City, Lee’s Projects, to some extent, resonate with her experience of identifying and negotiating with new cultures, places and communities in an unfamiliar foreign environment. Her series of works bring to the fore debates in the social sciences and cultural studies around issues of multiculturalism and post-identity, as well as new critical approaches to thinking globalism and cosmopolitanism, which have become prevalent since the 1990s.

This article will draw on the theoretical works of Alison Weir, José Esteban Muñoz and Paul Gilroy in the discussion of Lee’s performative photographic practice, which images and imagines identity as relational, formed and reformed via identification with diverse others. After reviewing feminist theories on the constitution of collective identities over the past three decades, Weir argues that the concept of “identification with” opens up a “liberatory dimension of identity politics,” through which identity is considered no longer a static category that enforces “sameness across group members,” but an active practice, based on “recognition of the other, and an openness to transformation of the self.”2 With her Projects, Lee constructs and images her multiple selves through continual acts of self-making and rebuilding relationships with others. In the meantime, rather than a seamless integration, her photographs often make visible subtle disparities between herself and each adopted community, challenging people’s preconceptions of collective existence in relation to coherence and uniformity. Her practice, in this way, also demonstrates an important, disidentifying aspect of identification that has been discussed and theorised by Muñoz, which neither completely accords with nor directly overthrows ingrained cultural paradigms, blurring a clear division between similarity and difference. In what follows, I examine how Lee’s Projects practice identity politics as continuous, intersecting processes of identification and disidentification, extricated from the constraints of established categories of gender, sexuality, ethnicity, race, class and nationality. Moreover, by extending from Weir and Muñoz to Gilroy’s discussion of the notion of “conviviality,” this article also investigates how Lee’s strategic engagement with vernacular popular cultures and stereotypical images of varied social and ethnic groups might forge intercultural, interpersonal interactions marked by spontaneous tolerance and openness outside governmental initiatives, provoking new reflections on one’s encounter with alterity and difference, which are not deformed by anxiety, fear and violence.3

Lee’s Projects were created and widely circulated via exhibitions and photographic books over the years during the so-called “post-identity” phase of Euro-American culture, which proclaims the collapse of all existing social, racial, cultural and political boundaries and hierarchies in identity formation. Especially in the early 2000s, works from her Projects were presented in a series of group exhibitions held in America, including Subject Plural: Crowds in Contemporary Art (Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, 2001), White: Whiteness and Race in Contemporary Art (Center for Art, Design and Visual Culture, University of Maryland, Baltimore, 2001), Only Skin Deep: Changing Visions of the American Self (International Centre of Photography, New York, 2003) and Manufactured Self (Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, 2005), to just name a few.4 These exhibitions investigated issues of race and ethnicity from different angles, while unravelling the complex, intersectional and constructive nature of individual and collective existence so as to challenge any fixed, static conception of racial and ethnic classifications. Held in a particular historical and socio-political context, these exhibitions reflected on public debates about “post-identity” in close connection with the implementation and demise of multiculturalism, and the rhetoric of “political correctness” especially dominating the United States since the late 1980s.

Multiculturalism, as a complex of ideologies and policies, played a decisive role in the governance and accommodation of ethnic and cultural diversities. However, with the decline of welfare states, as well as the growing concern about transnational immigration, political parties and governments especially in Europe and North America began proclaiming the failure of an unrealistic and illegitimate multiculturalism around the late 1990s and early 2000s. Gilroy has described this particular socio-political situation as “the plight of beleaguered multiculture.”5 As he has suggested, confronted with the unprecedented precarity and instability of social life under the impact of global capitalism, diversity is increasingly believed to be “a dangerous feature of society,” which “brings only weakness, chaos and confusion,” whereas unanimity is more likely and easily to give rise to strength and solidarity.6

Indeed, cautiousness and uncertainty about difference and alterity have become even more evident since the 9/11 terror attacks initiated the “War on Terror” response by the US and its allies. A series of new, stringent immigration policies and regulations started to be conceived and enacted in major Euro-American countries, which tended to divert public attention from internal conflicts within national states to anxieties about migrants, foreigners and strangers. The relevant debates about the rise and fall of multiculturalism bring about an important shift from identity politics to the discourses of post-identity. According to Amelia Jones, post-identity rhetoric relegates identity politics to the past and proposes a form of individual existence which is no longer affected by factors of race, ethnicity, gender and sexuality.7 It indicates that we have gone “beyond” identity and considers activist movements since the 1960s relating to civil rights, feminism, lesbian-gay rights and other progressive social and political aims outmoded or even dangerous to the integration of the nation, as they value difference over assimilation.

Grounded in the American context where Lee created most of her Projects, the discussion of post-identity in connection with a series of terms, such as “post-feminism,” “post-black” and “post-race,” also parallels the rhetoric of political correctness—the emergence of an inclusive “official language” that attempts to avoid the offence and exclusion of marginalised, disadvantaged groups in society by downplaying inevitable social disparities, hierarchies and antagonisms. The dominant debates around post-identity and political correctness reinvigorate the old idea of the American dream, which features America as an idealised national “home” with class mobility and social equality. Individual subjects can gain value and change their living and economic conditions through personal efforts, completely liberated from the constraints of identities and established power structures.

From appearance, Lee’s Projects of continuous self-alteration across multiple identity categories conform to political ideologies relating to post-identity as linked to the American dream of individual success, demonstrating an apolitical move away from identity politics. However, Lee’s infiltration into various social and cultural groups is, in fact, realised through her strategic use of photography in combination with staged performance. To a large extent, her performed collective attachment programmed for the camera exactly indicates the impossibility of her assimilation in real life. Despite Lee’s bodily proximity with different crowds of people shown in her photographs, her hardly concealed, distinctive Korean facial and physical features, as well as her mutating presence throughout different Projects, still lay bare her status of “otherness.” Lee’s practice is never an unthoughtful celebration of identity as a free, self-determined choice. Instead, her works, I would argue, engender multiple, open identifications across intersecting issues of nationality, ethnicity, race, gender, class and sexuality. Her own complex, intersectional identity as a Korean national, a heterosexual woman and an artist who is well-educated and privileged with essential financial and institutional support also further complicates people’s identifications with her photographs.

Lee’s first project was The Drag Queen Project, created in 1997. Although this series only includes four photographs, it reveals the performative and constructive nature of a particular subcultural persona, exploring the fluidity and contingency of both identity and identification and bringing to the fore issues of gender and sexuality. Wearing a black sequinned dress, long black gloves and stiletto heels, Lee has herself photographed hanging out in a Manhattan drag club. Her ensemble is complete with heavy makeup and a platinum blonde wig. In one photograph (fig. 1), Lee sits beside a drag queen who has already put on the costume and makeup for his temporary gender transformation. Lee embraces his arm and rests her head on his shoulder. The juxtaposition of Lee’s comfortably exposed, smooth female body with the drag queen’s much more muscular physique concealed under the skin-coloured undershirt casts doubt on people’s assumption of femininity. In another photograph (fig. 2), Lee stands in the middle of three drag queens, all dressed in evening wear with high heels and a wig. They stand together as a “community.” However, the height difference between the petite Lee and other three towering white drag queens indicates her status as an “outsider”—a woman who mimes a man miming a woman. Her unconcealable facial features of relatively smaller eyes and a flatter nose, in spite of her heavy makeup, also underline her intrusion into a subcultural milieu, which has been historically and is still dominated by white male performers.

According to Weir, to identify with another we must have the capacity to “travel to her world,” so as to enable our recognition of her experience and her resistant agency, and shift our relation from indifference to interrelated interdependence.8 Lee’s work demonstrates her capacity of travelling to the world of people she mimes, conveying her willingness to learn about the other and transform the self, as well as the relation between each other. Through observing and adopting the visual and behavioural conventions of the drag queen community, she approximates herself to an acceptable member, creating moments of social collectivity presented and documented by a selection of snapshot photographs. Lee’s immediate interrelation with those drag queens does not simply reveal her own identification with the group. It also allows members of the group to reconsider their identity and collectivity and go through a similar process of self-transformation on the basis of their interaction and negotiation with Lee, who performs as a temporary member, delineating a liminal domain in-between inclusion and exclusion.

As her first set of works, The Drag Queen Project plays a constructive role in shaping Lee’s practice of identification, which, as Louis Kaplan has also suggested, sets up “a functioning template” for her later performance as a member of a wider range of social and cultural groups.9 According to Judith Butler, drag instantiates an “imitative structure by which hegemonic gender is itself produced and disputes heterosexuality’s claim on naturalness and originality.”10 Via hyperbolic masquerade and performance on stage, drag, as Butler has indicated, both affirms and collapses the legitimacy of heterosexual gender norms. By miming a subcultural “female” gender role, adopted and falsified by male performers, Lee obscures her naturalised “womanliness,” traversing a clear line of demarcation between male and female, heterosexuality and homosexuality. Her practice aligns with the performative mechanism of drag, which reiterates, yet, at the same time, destabilises the legitimating norms and traditions of her adopted group. Lee’s Korean identity also engenders an additional dimension to consider the contingent and complex constitution of gender and sexuality, which intersect with race, ethnicity and nationality. Always demonstrating certain playful, theatrical subversion, her works never completely conform to the presumed image of people she tries to blend into. As mentioned previously, this recalls what José Esteban Muñoz has termed as disidentification.

According to Muñoz, “disidentification is a performative mode of tactical recognition that various minoritarian subjects employ in an effort to resist the oppressive and normalizing discourse of dominant ideology that fixes a subject within the state power apparatus.”11 Described as a survival strategy especially utilised by queer people of colour, disidentification proposes an intersectional approach to resistance, crossing over identity categories of not only gender and sexuality, but also race, class and ethnicity. Obviously, Lee’s works of infiltrating into both cultural groups of the white majority, such as yuppies and neo-swing dancers, and subcultural communities, such as drag queens and black hip-hoppers, do not exactly accord with the minoritarian-majoritarian opposition defined by Muñoz in his discussion of disidentification. Nevertheless, her incomplete integration into each adopted community revealed in her photographs is in line with disidentification as a strategic “reformatting of the self within the social,” which neither assimilates with dominant ideology, nor strictly subverts it, traversing the tidy binary divide of identification and counteridentification.12 Here, the dominant ideology refers to any coercive idea that reinforces a fixed, unified individual or group identity or simply negates identity and cultural differences. Moreover, in consideration of Lee’s ambiguous status as both an outsider and a privileged artist in charge of the production and presentation of her photographs, her practice of disidentification does not really aim for tactical survival, which requires cautious negotiation and compliance. Instead, it often demonstrates more blatant sarcasm and playful exaggeration normally seen in drag performance, which, to a great extent, challenge people’s habitual perception of legitimating norms and stereotypical images, foregrounding the fluid and relational nature of identification and disidentification.

When exhibited, select works from Lee’s different Projects are often juxtaposed with one another in a seemingly inadvertent manner. Lee usually attends the exhibition openings, introducing herself and her works. The real-life encounter with the artist enables viewers to consider Lee’s dramatic physical alteration beyond the surface of her photographs and visualise similar transformation of themselves into other subjects. Indeed, this immediate interaction between viewers and Lee is still largely operating on a visual level. Some viewers also ask Lee to take snapshots with them in front of her works, which further complicates the interrelation between staged performance and everyday experience captured via photographic practice. In his recent book Inadvertent Images: A History of Photographic Apparitions, Peter Geimer proposes a new methodological perspective which tends to undercut the dichotomies of fabrication and truthfulness, orchestration and spontaneity in the study and theorisation of photography.13 Lee’s practice aligns with Geimer’s discussion of photography in which “artificiality and naturalness, construction and incident” are far from being mutually exclusive, but intertwining with one another.14 In Lee’s Projects, photography is not simply rendered as a detached medium of representation. Rather, it has been infused with a tangible form of physical reality in close association with the artist’s embodied appearance and performance in the production or even reception of her works of art. Viewers are propelled to engage in a process of (dis)identifying with a complex range of intersecting visual signifiers that cross the clear boundary between reality and fiction. Their interpretations and readings of each photograph can be also drastically diverse, as they locate themselves differently in relation to issues of race, gender, sexuality, religion, class and nationality that frame their understandings and perceptions of Lee as the artist and her varied performed identities demonstrated in her works.

Undoubtedly, Lee’s employment of mundane snapshots also constitutes a major element in forging this intricate situation of interpersonal, intersubjective (dis)identifications, which makes her Projects distinct from the staged photographic self-portraits created by American artists of the previous generation, the works of Cindy Sherman in particular. Due to the similar mode of identity impersonation via masquerade, clothing and props, Lee’s practice has been frequently associated by scholars with Sherman’s ground-breaking Untitled Film Stills (1977-1980). However, in contrast with Sherman’s carefully composed photographs of diverse female roles taken in her individual studio within fabricated tableaux, Lee’s snapshots, which appear to be spontaneous and unscripted, advance further in blurring the distinction between the photographic documentation of quotidian life and of actions and emotions staged specifically for the camera. On the one hand, Lee’s amateur snapshots, complete with visible flaws of composition and crude lighting, create an air of authenticity, in conformity with the dominant objective of verisimilitude in photography. On the other, Lee also questions the truth value of her snapshots by using them to document a performed, simulated life, disrupting the rawness and immediacy revealed in them. In this way, Lee’s practice develops a critical insight into what Catherine Zuromski has called as “the culture and complexity of snapshot photography itself.”15 Guided by dominant social norms and cultural ideals, the tropes of domestic bliss, interpersonal intimacy and social harmony have become iconic images of mundane snapshots.16 People incline to perform intimacy and show gestures of mutual affection in front of the camera. It is this aesthetic convention of snapshot photography that permits Lee to stage the falsely signified “intimacy” with her adopted groups —”a quality of extended engagement normally based on deep knowledge, rapport and trust,” as Miwon Kwon has discussed in relation to Lee and also the work of Filipino American artist Lan Tuazon.17

Furthermore, unlike Sherman’s exploration of the socially and culturally constructed femininity especially in relation to white middle-class women, Lee’s practice of self-performance and self-alteration on the basis of her interactions with diverse sociocultural groups adopts a much more intersectional approach to identity and identification. By investigating “a history and theory of identification in the visual arts,” Amelia Jones suggests “a provisional new model for understanding identification as a reciprocal, dynamic, and ongoing process that occurs among viewers, bodies, images and other visual modes of the (re)presentation of subjects.”18 Lee’s Projects, I would suggest, demonstrate a similarly complex network of ever-shifting, hybrid and crossed (dis)identifications with a range of subjects and images. This also enables an alternative, different insight into her practice. Lee’s works, over the past decade, have been often examined by scholars in connection with theoretical debates about contemporary community-based art, in which the artist works as a quasi-ethnographer to represent the life of a specific living community. In his 1996 book The Return of the Real, Hal Foster criticizes the apparent authority of the artist as the ethnographic participant-observer in contemporary community-based art, which tends to be unquestioned and unacknowledged.19 For Foster, due to the uneven power relation between the artist-ethnographer and the observed group, “almost naturally the project strays from collaboration to self-fashioning, from a decentring of the artist as cultural authority to a remaking of the other in neo-primitivist guise.”20 Following Foster’s discussion, scholars, like Kwon, have interrogated the works of Lee and others for abstracting and objectifying those groups they are temporarily involved in by virtue of manipulating and reinforcing pre-existing stereotypes.21

I agree that Lee’s integration into, for instance, the drag queen community by wearing their recognised clothing and makeup and visiting drag nightclubs could initially be perceived shallow and superficial, which, to some extent, blunts the political effectiveness of her practice of identification. I will come back to this point. However, I also want to suggest that Lee, in her works, never intends to “go native” or provide a comprehensive account of the culture and experience of those communities she travels into. Instead, her practice attaches more importance to a multifaceted, productive and substantive process of identification and disidentification, exploring how diverse groups of people are visually identified and constructed in society. Similar ideas have been also addressed by Coco Fusco in her article written for the 2003 exhibition, Only Skin Deep: Changing Visions of the American Self, in which a number of works from Lee’s Projects were presented. For Fusco, Only Skin Deep neither simply affirms nor negates, but rather studies the social impact of photographs which make cultural and racial classifications visible and shape people’s changing perceptions of what Americans look like.22 Likewise, Lee’s works investigate and demonstrate the ways in which images and stereotypes constitute an indispensable part of our perception and imagination of where people come from and who they are, so as to engender a range of cultural interpretations. I wish to explore this specific aspect of Lee’s practice further, as it has been never discussed in-depth in existing literature, by looking at some of her later works in the Projects series more directly associated with racial and ethnic impersonation.

As Cherise Smith has argued, Lee’s practice “demonstrates her impressive ability to identify cultural groups that present complexly intersected identifications.”23 This, in particular, is shown evidently in some of her Projects in which she performs racial “passing,” identifying and disidentifying stereotypical semiotic codes imposed on categories of race and ethnicity. Looking at The Swingers Project (1998-1999) and The Hip Hop Project (2001), this aspect is made unmissable by the foregrounding of cultures visibly coded as foreign to her own. According to José Esteban Muñoz, passing and disidentification resemble each other, as passing, like disidentification, can be “a third modality where a dominant structure is co-opted, worked on and against.”24 The subject who passes, as Muñoz suggests, “can be simultaneously identifying with and rejecting a dominant form.”25 Nevertheless, passing, in the history of racial segregation, refers to the efforts of lighter-skinned black subjects who strived to gain entry to white society. In this case, as Smith argues, “to pass successfully, one must suppress one’s own difference from and perform the behaviours of members of the dominant culture in order to appear like them.”26 Thus, passing, in the traditional sense, is a far cry from a theatrical, disidentifying performance, as it “seeks to erase, rather than expose, its own dissimulation.”27 Lee’s disidentifying performance of “passing,” which obscures identity boundaries with playfulness and exaggeration, I want to suggest, significantly unhinges the notion of passing from its conventional narratives on race and ethnicity. In most of her works, Lee candidly exposes and, at times, even highlights her “outsideness,” creating a visual interstice owing to her simultaneous sameness to and difference from the assumed identities she temporarily adopts. In this way, her practice commits to a shift from passing to racial and ethnic performance.

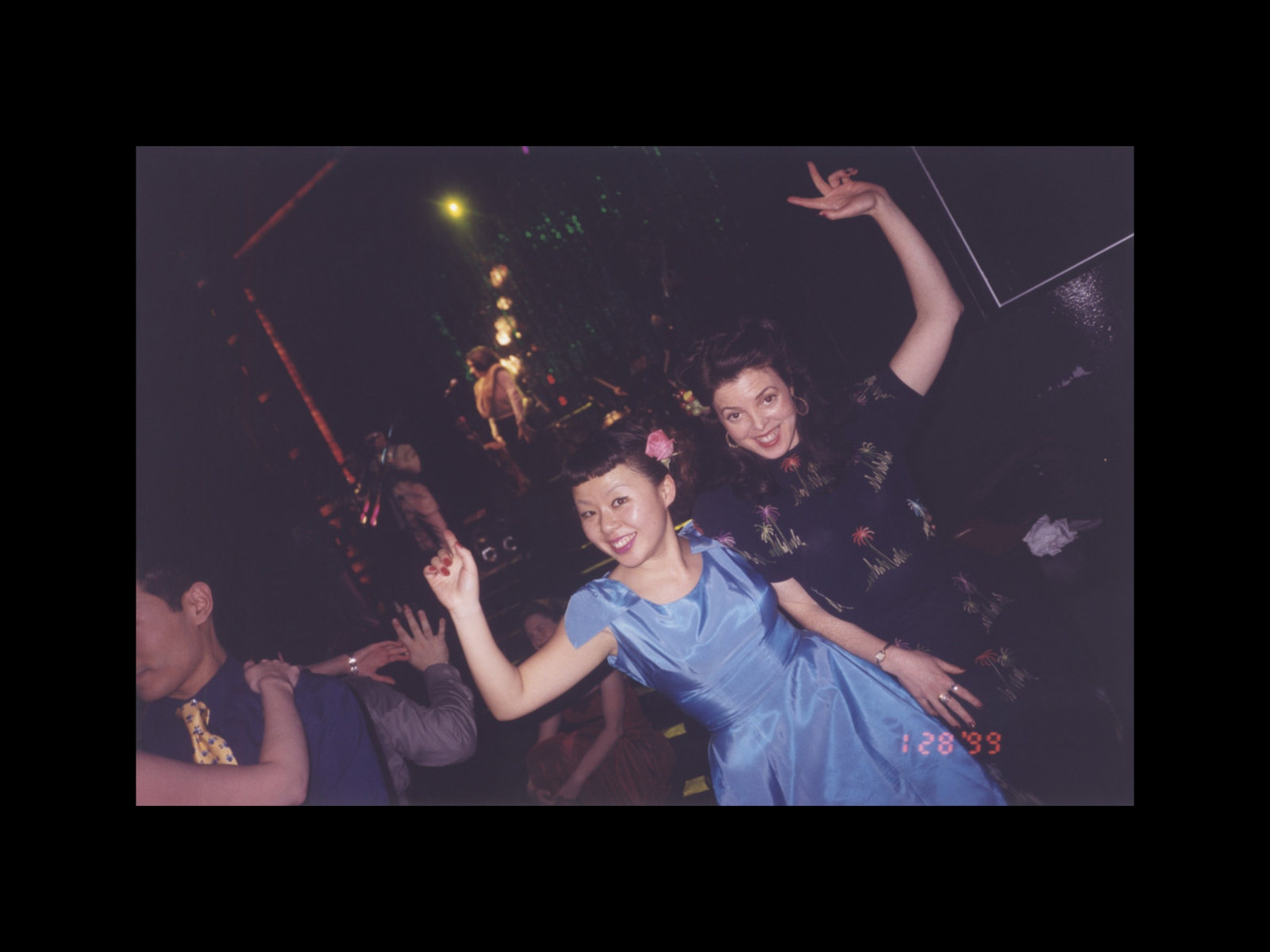

In one photograph from The Swingers Project, Lee dances with a female friend in a nightclub (fig. 3). Lee wears a light blue sleeveless bubble dress, whereas her friend is in an old-fashioned dark flapper costume. Both women have a 1940s-pin-up hairstyle. Lee’s companion wears her hair in side parted victory rolls, while Lee keeps her faux bangs and shoulder-length curls. In spite of the fact that the photograph is terribly framed, it is not difficult to tell that Lee and her friend are participating in a dance party. They are surrounded by other dancers, whose presence can be discerned through those cut-off arms and shoulders in the photograph. The backdrop of the image is a stage. A woman who wears a furry tippet is singing in front of a music band. This photograph, which is stamped with the time “1-28-99,” appears somewhat anachronistic, as all figures are dressed in a vintage style that was popular during the time of the Second World War.

The Swingers Project centres around the so-called neo-swing culture, which emerged in major American cities in the 1990s. According to music historian Eric Martin Usner, neo-swing is a cultural re-enactment of swing music, dance and fashion which prevailed in the 1930s and 1940s in America.28 The majority of its group members are white middle-class youth, who are not only interested in swing culture, but who also attempt to resurrect “the social etiquette, morality, and ideals of a past generation” in the present, through their active participation in an old-style social dancing performance.29 The formation of this youth culture is based on a nostalgic fantasy of a historical period, in its practitioners’ words, “when men were men and women were women” and social interactions between couples were “healthful and respectful.”30

This revival of swing culture is inevitably connected with the specific socio-political environment in America. In her book The Queen of America Goes to Washington City: Essays on Sex and Citizenship published in 1997, Lauren Berlant writes that “portraits and stories of citizen-victims,” since the Reagan-era, have been used to create a new national discourse of American citizenship.31 In this way, “a citizen is defined as a person traumatised by some aspect of life in the United States,” demonstrating “a mass experience of economic insecurity, racial discord, class conflict and sexual unease.”32 This coupling of suffering and citizenship, according to Berlant, seeks to individuate the experience of social precarity and instability and “substitute intentional individual goodwill for the nation-state’s commitment to fostering democracy within capitalism.”33 In tandem with the rhetorics of post-identity and political correctness discussed at the beginning of this article, it similarly suppresses the complexity and ambivalence of sexual, racial and ethnic structures and relations of exploitation in American society, in order to contrive an idealised mode of democratisation. Individuals, regardless of their personal backgrounds, are supposed to take the responsibility themselves for fighting with everyday violence and economic difficulties. The political discourses of citizenship crisis, while, from appearance, seek to dilute negative stereotypes concerning cultural, sexual and ethnic minority groups, also make formerly iconic citizens—white, upper-middle-class, heterosexual Americans feel that they have been deprived of their national privilege, giving rise to a strong desire in them to return to a previous order of American life.34 The rise of a neo-swing culture among white middle-class youth in the 1990s aims precisely at restoring the so-called lost national iconicity and cultural hegemony, historically related to heterosexual whiteness.

In another photograph, Lee is standing in the middle of four white men on the porch of a white wooden house (fig. 4). Behind them, an oversized American flag hangs from the interior ceiling. Lee wears a vintage red dress and pins up her hair with a red snood. A red flower is positioned behind her left ear, paired with the colour of her outfit and lipstick. Three men standing beside Lee wear Panama straw hats and short-sleeve tropical-print shirts. The fourth is in a white vest and plaid shorts. The title indicates that the photograph belongs to The Swingers Project, although it was not taken in a ballroom setting. Lee’s easily recognised East Asian face reveals her “outsideness” in this predominantly white community. As swing dancing is usually considered a typical heterosexual social activity between lovers and couples, Lee might be perceived as the partner of one of the men standing around her, with whom she gets involved in this patriotic scene in front of Old Glory as part of her process of “Americanization.” The clothing style and postures of all figures in the photograph demonstrate fairly entrenched heterosexual gender norms. As Berlant has also suggested, despite the panic and anxiety about immigration, women are often featured as good immigrants who are more likely to become real citizens and achieve ultimate cultural immersion through consensual marriage (with white men) and giving birth to the next generation.35 This brings to the fore another aspect of the privatisation of American citizenship in crisis, which prioritises the values of heterosexual reproductive families in the constitution of a “post-racial” but still “white-enough” American future through interethnic marriage and crossbreeding.

The Swingers Project engenders multiple, complicatedly intersecting (dis)identifications relating to people’s understandings of swing culture, as well as dominant political ideologies and racial and ethnic structures in America. As for members of the neo-swing group Lee mimes, their re-enactment of swing dancing articulates an intricate interrelation of identification and disidentification with the ideology of citizenship crisis they tend to subvert. Their attempts of revitalising swing culture, on the one hand, typically correspond to the deep-rooted power structures and forcible regimes of white supremacy and heteronormality in American society. On the other, by reinstating white pride and heterosexual norms through an entertaining and theatrical vernacular social activity, the group also offers an alternative perspective to consider and negotiate state ideologies from below with individual understanding, misunderstanding and disparity, which creates a more tolerant, convivial and flexible environment for possible subversive intervention and disidentification.

Via Lee’s performance of “passing” into the neo-swing community, whiteness, normally rendered as an invisible racial category, is specifically observed and studied. Lee’s practice unfolds not the flexibility or elasticity of identity completely freed from borders and limitations, but the impossibility of being fully included into a white community. Through her imitative performance as a member of the group, she both identifies and disidentifies with the assumed white superiority ingrained in American society, revealing its performative and contingent constructedness. While Lee tries to integrate herself into the group by adopting a stereotypical swing style and practicing swing dancing, those white neo-swing dancers also engage in a continuing process of self-fashioning and performance, through which they iterate and reiterate their identity, attempting to restore the social prestige of whiteness. Furthermore, in this series, Lee also plays with the title of her photographs. The word, “swinger,” refers here not only to a swing dancer, but to a person who has sex with multiple partners, which evokes a situation contrary to the normalised nuclear family life. Rather than portraying herself as a migrant woman, easily assimilated into the dominant American culture, Lee, by virtue of her ironic use of polysemy and ambiguous practice of (dis)identification with the neo-swing culture, disrupts and challenges the political and governmental advocacy of the family unit as the location of the production and reproduction of tacitly white, heterosexual hegemony.

Even more importantly, according to Usner, swing was originally “an interracial appropriation of an African American music and dance by members of white immigrant groups” settling in America, which cut across racial and class lines. However, since the Second World War, it has been usually falsified as “predominantly white.”36 For the formation of “a unified national consciousness during the wartime,” a homogeneous, typically white image of swing culture was constructed, which still influences people’s perception of the so-called swing era. 37 Swing culture, in this way, is divorced from its historical realities and transformed into an idealised image of white norms and privilege. The Swingers Project, in effect, depicts a group of young people who perform and reconstruct their white identity according to a mistaken historical trope of white homogeneity and dominance produced by patriotic ideals and mass media industries.

By imitating fashion styles and social norms of swing culture selectively adopted by neo-swing white youth, Lee’s “passing” into the community complicates the inter-racial background of this vernacular popular culture, further blurring the racial bifurcation of white and black. At the same time, this series of photographs might be also criticised for reaffirming and reinforcing the problematic misrepresentation of swing culture. Yet standing in front of Lee’s works, any claims that could be made about cultural authenticity and purity tend to become naïve and facile. With The Swingers Project, Lee reveals the compatibility and inclusiveness of vernacular culture which generate open possibilities for interpersonal engagement and interaction, giving rise to multiple, shifting identifications and disidentifications in association with viewers’ own cultural and racial positioning. Lee’s performance of racial and ethnic “passing” provokes reflections on people’s encounter and cohabitation with difference and alterity, which can also be explored with The Hip Hop Project.

As the last series of her Projects, The Hip Hop Project was commissioned for the exhibition, One Planet under a Groove: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art, curated by Lydia Yee and Franklin Sirmans, and held at the Bronx Museum of the Arts in 2001. The exhibition provided a distinctive insight into the thirty-year evolution of hip-hop by investigating its dynamic interaction with contemporary art and inevitable integration into global capitalism.38 Held about four months after Thelma Golden’s exhibition—Freestyle presented at the Studio Museum in Harlem which coined the term “post-black,” One Planet under a Groove, with the works of more than thirty artists from diverse sociocultural and geopolitical backgrounds, explored and demonstrated hip-hop as a highly commercialised, “trans-racial,” global culture industry, acknowledging, but, at the same time, challenging its exclusive connection with the popular imagination of blackness in American society. In this series, Lee attempts to “pass” as a black woman, probing into the complicated, intersectional racial background of hip-hop culture.

In the most widely discussed photograph of Lee in this series, she sits alongside four young African Americans on the back of a car (fig. 5). Lee has transformed herself into a “black” girl by tanning her skin darker and adopting the attitudes of a rapper’s entourage. She is seated between the legs of Prodigy—a member of the hardcore hip-hop group Mobb Deep. Lee is in a low-cut black dress adorned with a gold chain belt, which calls to mind the “bling” excesses of jewellery and accessories that typically characterise the materialistic absurdity of hip-hop culture in its more recent guises. Prodigy slightly raises his eyebrows, staring scornfully at the camera while making a hip-hop gesture of address. This photograph foregrounds a sustaining tension of contemporary hip-hop between the attempts to maintain its authentic, confrontational street credibility closely connected with the imagery of black masculinity, and its unprecedented openness and tolerance to diversities and differences under the capitalistic impulse of mass consumption. Lee’s involvement with the community, to some extent, illustrates a mode of group membership extricated from any culturally specific racial identity. Instead, it is largely formulated by the purchase, display and manipulation of certain fashion and commodity codes, as well as imitative performance of hip-hop gestures and demeanour.

Embraced by other group members, Lee’s artificially tanned face and body via sun beds and cosmetics can be easily discerned. The colour of her arms and chest is lighter than her exaggeratedly dark-toned face. Lee also overstates her Korean features by the use of eye makeup. This is shown more explicitly in another photograph of Lee taken with two black female dancers (fig. 6). The photograph is cropped at about their waist. The three women smile to the camera. This time, Lee’s hair has been braided into cornrows. A pair of sunglasses rests on her head. Her eyebrows have been shaved thin, and are finely arched. Eyeliner has been applied, as Cherise Smith has described, “past the outside corners of her eyes, highlighting Lee’s almond-shaped eyes with epicanthic folds”—one of the most stereotypical facial features of people with East Asian origins.39

As many scholars have argued, Lee’s performance of “passing” for black in The Hip Hop Project recalls the dynamic history of Asian and African interaction via hip-hop culture. 40 Asian American martial art has a far-reaching influence on the development of hip-hop aesthetics. Elements, such as wrestling in breakdance and graffiti and tattoos in Oriental scripts, significantly diversify its cultural constitution and identification. Meanwhile, young Asian Americans, over past few decades, have turned into one of the major consumer groups for hip-hop.41 They buy hip-hop music and other relevant products, and adopt the clothing, hairstyle and language of black hip-hop stars, which have also enriched the ways they are visually identified in American society. Lee’s series of photographs taken when practicing hip-hop dance and hanging out with members of an apparently black-dominated hip-hop community draw attention to this productive inter-racial engagement and identification within this particular cultural milieu.

In the meantime, Lee’s approach to this series has been also frequently compared to traditional minstrel performance in which white performers mime black style and sing black popular music on stage, reinforcing their dominance over black bodies.42 Undoubtedly, Lee’s practice demonstrates her artistic supremacy which enables her to “pass for black” at will but with recognisable difference. Nonetheless, Lee’s works, I would argue, are very different from white minstrels’ parodic, racist impersonation of black subjects, which attempts to consolidate a fixed racial division of white and black. With her highlighted Korean features and hardly classified skin tone, Lee’s performance of “passing” challenges any absolute assumption of social, cultural or racial specificities of hip-hop culture, disidentifying its normalised, stereotypical association with blackness. In her photographs, the black hip-hop dancers are not featured as inferior or even barbaric subjects for public amusement as shown in white minstrelsy. Rather, they are privileged as one of the select social groups that Lee makes efforts to blend into for the sake of her artistic exploration of the culturally and socially heterogeneous America. The Hip Hop Project, in this sense, exists to subvert a more traditional conception of passing, as usually conducted from black to white, from the marginal to the mainstream.

As an unclassifiable, ironically racialised “passer,” Lee’s appearance in her photographs invokes varied identifications and disidentifications with not only hip-hop culture, but public representations of Asianness and blackness in America. This obviously contrasts to those critical charges of her manipulation and exploitation of a black culture to which she does not belong. As mentioned earlier, hip-hop, as a commercialised mass culture, is no longer exclusively linked to black subjects and relevant conversations around counterhegemonic politics and black movements. Instead, it has been adopted by people of multiple racial, social and ethnic backgrounds to establish their own community connections and to bring in new cultural elements to the form. Rather than presenting a presumably static and consistently black vernacular culture, The Hip Hop Project gives weight and traction to its productive mutability and openness that allow various interpersonal, intercultural interactions and (dis)identifications to come to the fore.

By drawing on examples from pop music and television comedy, Paul Gilroy proposes the idea of “conviviality” and discusses the ways in which spontaneous, organic vernacular mass culture may cultivate healthier relationships with otherness outside governmental actions and initiatives.43 According to Gilroy, conviviality refers to “the process of cohabitation and interaction” which demonstrates a radical openness that “makes a non-sense of closed, fixed and reified identity and turns attention toward the always-unpredictable mechanisms of identification.”44 Given the fact that Gilroy grounds his discussion mainly in his own British context, investigating British colonial history, racial politics and recent immigration policies, his notion of conviviality, I would suggest, can be also instructive to the study of Lee’s works which give rise to intricate identifications and disidentifications with a wide range of vernacular cultural communities.

The inclusive conviviality of vernacular culture described by Gilroy is evident in The Hip Hop Project. Lee “passes” into a black hip-hop community, via theatrical performance and hyperbolic masquerade that actually underline her “outsider” status. Her temporary infiltration into the group as an acceptable member demonstrates a convivial process of cohabiting and interacting with differences, in which both Lee and members of the group are prompted to reconsider their perceptions of hip-hop culture and their own identities via mutual (dis)identifications. Lee’s “otherness” presented in her photographs is never clearly and stably identifiable as a neat, tidy category. Rather, it is always subject to change, constitution and reconstitution through her reciprocal exchanges with each adopted community and viewing subjects.

According to Gilroy, contemporary hatred and fear about otherness often lie in the menace of “the half-different and the partially familiar”—the inability of locating “the other’s difference in the common-sense lexicon of alterity.”45 As shown in The Hip Hop Project, Lee, in her works, typically embodies the half-familiar, half-strange otherness, which cannot be easily located and induces anxieties about the loss of cultural integrity and authenticity. However, via the unruly, spontaneous, cheerful and funky scenes of hip-hop culture, which are too inclusive and diverse to give an unequivocal, distinctive definition of otherness, Lee, with her photographs of deliberately chosen, convivial moments of community life, presents new ways of imaging and imagining social collectivity with unfamiliar others that people would possibly rather not know and see, based on not seamless sameness or coherent identification, but tolerance, openness, as well as mutual recognition and respect. With her darkened face and overstated eye makeup, Lee tends to release people’s anxieties and hostilities about difference and alterity through laughter. As Gilroy has suggested, artistic and cultural practices cannot provide an antidote to existing problems, but they call for something bolder and more imaginative to reconsider our living situation and interpersonal connectedness without becoming anxious, fearful or violent.46

Nevertheless, at times, Lee’s practice could be also too “convivial,” completely shying away from issues of struggles and conflicts in society, which, to some extent, takes the edge off her artistic disidentification and subversion. In her photographs, **members of her adopted groups, whether drag queens, neo-swing dancers or hip-hop rappers, all look happy and satisfied with their individual and collective living situations. Her temporary, negotiated engagement with these groups largely depends on her adoption and appropriation of their easily identified, idiosyncratic dress codes and admittedly theatrical lifestyles, intimately connected with the increasing marketisation and commercialisation of culture under the force of global capitalism. Yet in her practice, Lee never seeks to investigate thoughtfully the critical role of mass consumption that allows her to stretch and redefine the boundary of each community and forge convivial scenes of vernacular cultural collectivity. Embellished with apparent frankness, her mundane snapshots, as discussed earlier, provoke viewers’ imagination about similar embodied processes of self-alteration beyond her photographs. However, they are only capable of capturing performed instants of her collective engagement, but inadequate in revealing her real-life experience of interacting and negotiating with every adopted group across established socio-political and cultural boundaries which may somehow hinder her transgression. Thus, Lee never travels to the world of others in the manner described by Weir in her discussion of “identification with,” which needs to realise and take into account other people’s social power relations and resistant agency.47 Possible difficulties and frictions in the construction of tolerated, convivial connections with diverse others are hardly addressed in Lee’s works and conveyed to viewers.

Despite engendering a range of intersecting (dis)identifications in relation to viewing subjects and multiple social and cultural groups, Lee’s Projects, in effect, still prioritise her own self-transformation that connects her different series of works together and forms a key measure of her artistic accomplishment. Her seemingly indiscriminating integration into groups of both the white mainstream and other minority collectives with the same zeal and desire therefore runs the risk of erasing the historical and cultural substance on which various (dis)identifications are based, leading to a “post-identitarian” condition. This is, actually, in contradiction to Gilroy’s conception of vernacular conviviality, which demands the recognition of histories of racial divisions and hierarchies. For Gilroy, these histories are of great importance in nurturing a multicultural society, as they underpin and frame our current understanding and perception of the world, our own existence and people around us.48 In this sense, Lee’s Projects, I suggest, require a more critical insight into the broader social, cultural and political forces that render her adopted communities hegemonic or marginal, privileged or disempowered in society. Otherwise, they risk becoming subordinated to the very “politically correct” narratives of “post-identity” and shared “citizenship crisis,” which aim to create an idealised image of social and national conviviality by negating the complicated history of identity politics and activisms of the past. As well, these readings will miss the unavoidably uneven and variously antagonistic socioeconomic realities in the present.

-

Gilbert Vicario, “Conversation with Nikki Lee,” in Nikki S. Lee: Projects, ed. Lesley A. Martin (Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2001), 107. ↩

-

Alison Weir, Identities and Freedom: Feminist Theory between Power and Connection (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 65. ↩

-

Paul Gilroy, After Empire: Melancholia or Convivial Culture? (London and New York: Routledge, 2004), xi; 135. ↩

-

White was later also exhibited at the International Centre of Photography (2003-04) and Only Skin Deep was also travelling to the other two institutions—Seattle Art Museum (2004) and San Diego Museum of Art (2005). ↩

-

Gilroy, After Empire, xi. ↩

-

Ibid., 1. ↩

-

Amelia Jones, Seeing Differently: A History and Theory of Identification and the Visual Arts (London and New York: Routledge, 2012), xx. ↩

-

Weir, Identities and Freedom, 78-79. ↩

-

Louis Kaplan, American Exposures: Photography and Community in the Twentieth Century (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 193. ↩

-

Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex” (New York: Routledge, 1993), 125. ↩

-

José Esteban Muñoz, Disidentifications: Queers of Colour and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 97. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Peter Geimer, Inadvertent Images: A History of Photographic Apparitions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), 199. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Catherine Zuromski, Snapshot Photography: The Lives of Images (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013), 9. ↩

-

Ibid., 10. ↩

-

Miwon Kwon, “Experience vs. Interpretation: Traces of Ethnography in the Works of Lan Tuazon and Nikki S. Lee,” in Site-Specificity: The Ethnographic Turn, de-, dis-, ex- 4, ed. Alex Coles (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2000), 86. ↩

-

Jones, Seeing Differently, 1. ↩

-

Hal Foster, The Return of the Real (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996), 196. ↩

-

Ibid., 196-197. See also Miwon Kwon, One Place after Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004), 139. ↩

-

Kwon, “Experience vs. Interpretation,” 86. ↩

-

Coco Fusco, “Racial Time, Racial Marks, Racial Metaphors,” in Only Skin Deep: Changing Visions of the American Self, ed. Coco Fusco and Brian Wallis (New York: International Center of Photography, 2003), 13. ↩

-

Cherise Smith, Enacting Others: Politics of Identity in Eleanor Antin, Nikki S. Lee, Adrian Piper, and Anna Deavere Smith (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 207. ↩

-

Muñoz, Disidentifications, 108. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Smith, Enacting Others, 13. ↩

-

Valerie Rohy, “Displacing Desire: Passing, Nostalgia, and Giovanni’s Room,” in Elaine K. Ginsberg (ed.) Passing and the Fictions of Identity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996), 226. ↩

-

Eric Martin Usner, “Dancing in the Past, Living in the Present: Nostalgia and Race in Southern California Neo-Swing Dance Culture,” Dancing Research Journal 33, no. 2 (Winter 2001/2002): 92. ↩

-

Ibid., 89. ↩

-

Ibid., 90-91. ↩

-

Lauren Berlant, The Queen of America Goes to Washington City: Essays on Sex and Citizenship (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1997), 1. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid., 7 ↩

-

Ibid. 2. ↩

-

Ibid., 16; 179 ↩

-

Usner, “Dancing in the Past, Living in the Present,” 96-97. ↩

-

Ibid., 97. ↩

-

Raymond Codrington, Review on Hip-Hop: The Culture, the Sound, the Science (2002) and One Plane Under a Groove: Hip-Hop and Contemporary Art (2001; 2002; 2003), American Anthropologist, 105, 1 (March 2003): 155. ↩

-

Smith, Enacting Others, p. 220. ↩

-

Cathy Covell Waegner, “Performing Postmodernist Passing: Nikki S. Lee, Tuff, and Ghost Dog in Yellowface/Blackface,” in AfroAsian Encounters: Culture, History, Politics, ed. Heike Raphael-Hernandez and Shannon Steen (New York and London: New York University Press, 2006), 223-244. ↩

-

Oliver Wang, “Rapping and Repping Asian: Race, Authenticity and the Asian American MC,” in Alien Encounters: Popular Culture in Asian America, ed. Mimi Thi Nguyen and Thuy Linh Nguyen Tu (Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 2007), 61. ↩

-

Smith, Enacting Others, 13. ↩

-

Gilroy, After Empire, xi. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid., 139. ↩

-

Ibid., xiv. ↩

-

Weir, Identities and Freedom, 65. ↩

-

Gilroy, After Empire, 2-5. ↩

Vivian K. Sheng is an assistant professor at the Department of Fine Arts, The University of Hong Kong (HKU). She is currently working on her first book monograph—Art, Women and Fantasies of “Homemaking”: Affective Domesticity, Embodied Habitation and Transcultural (Dis)identification. Before joining HKU, she has also taught contemporary art history and theory at the University of Manchester, UK. Her writing has appeared in Sculptural Journal and Yishu: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art.

Bibliography

- Berlant, Lauren. The Queen of America Goes to Washington City: Essays on Sex and Citizenship. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1997.

- Butler, Judith. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex”. New York: Routledge, 1993.

- Codrington, Raymond. Review of Hip-Hop: The Culture, the Sound, the Science, The Museum of Science and Industry (2002) and One Planet under a Groove: Hip-Hop and Contemporary Art, The Bronx Museum of the Arts, Walker Art Center, Spelman College (2001; 2002; 2003), American Anthropologist, 105, 1 (March 2003): 153–6.

- Foster, Hal. The Return of the Real. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996.

- Fusco, Coco and Brian Wallis (Eds.) Only Skin Deep: Changing Visions of the American Self. New York: International Center of Photography, 2003.

- Geimer, Peter. Inadvertent Images: A History of Photographic Apparitions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018.

- Gilroy, Paul. After Empire: Melancholia or Convivial Culture? London and New York: Routledge, 2004.

- Jones, Amelia. Seeing Differently: A History and Theory of Identification and the Visual Arts. London and New York: Routledge, 2012.

- Kaplan, Louis. American Exposures: Photography and Community in the Twentieth Century. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005.

- Kwon, Miwon. “Experience vs. Interpretation: Traces of Ethnography in the Works of Lan Tuazon and Nikki S. Lee.” In Site-Specificity: The Ethnographic Turn, de-, dis-, ex- 4, edited by Alex Coles, 74–93. London: Black Dog Press, 2000.

- Kwon, Miwon. One Place after Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004.

- Martin, Lesley A. (ed.). Nikki S. Lee: Projects. Exhibition Catalogue. Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2001.

- Muñoz, Jose Esteban. Disidentifications: Queers of Colour and the Performance of Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

- Rohy, Valerie. “Displacing Desire: Passing, Nostalgia, and Giovanni’s Room.” In Passing and the Fictions of Identity, edited by Elaine K. Ginsberg, 218–33. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996.

- Smith, Cherise. Enacting Others: Politics of Identity in Eleanor Antin, Nikki S. Lee, Adrian Piper, and Anna Deavere Smith. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011.

- Usner, Eric Martin. “Dancing in the Past, Living in the Present: Nostalgia and Race in Southern California Neo-Swing Dance Culture.” Dancing Research Journal 33, 2 (Winter 2001/2002): 87–101.

- Waegner, Cathy Covell. “Performing Postmodernist Passing: Nikki S. Lee, Tuff, and Ghost Dog in Yellowface/Blackface.” In AfroAsian Encounters: Culture, History, Politics, edited by Heike Raphael-Hernandez and Shannon Steen, 223–42. New York and London: New York University Press, 2006.

- Wang, Oliver. “Rapping and Repping Asian: Race, Authenticity and the Asian American MC.” In Alien Encounters: Popular Culture in Asian America, edited by Mimi Thi Nguyen and Thuy Linh Nguyen Tu, 35–68. Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 2007.

- Weir, Allison. Identities and Freedom: Feminist Theory between Power and Connection. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Zuromskis, Catherine. Snapshot Photography: The Lives of Images. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013.